|

TRANSLATIONS

I have not yet convinced myself that the counting to π on side b should start with Ab1-1 (in contrast to the counting to π on side a which evidently begins with Aa1-2). Why should there be such a difference? If the difference really is there, i.e. is intended by the creator of the text, the reason possibly is to tell that the Beginning of the total text is at Ab1-1:

On the other hand, if the counting also on side b should start with the 2nd glyph, then the 288th (2 * 122) glyph would be Ab4-44:

292 = 4 * 73 (and 5 * 73 = 365) The shape of Ab4-44 is more slender and canoe-like than the tôa in the night:

This is especially noteworthy in the great glyphs around midnight. The parallel glyphs in H/P/Q instead belong to GD64 (rau hei):

I guess that fundamentally GD47 (tôa) depicts a type of canoe, and also that GD55 (tapa mea) - the corresponding time marker during the day - illustrates a canoe. In Aa1-45 the canoe image chosen is GD48 (vaka), while the ominous rau hei in the parallel texts are avoided in the other Tahua night glyphs and instead more neutral tôa were incised. But I guess that these tôa anyhow are to be interpreted as rau hei, which explains why the shape of tôa is fatter than normal. GD64 should be fat:

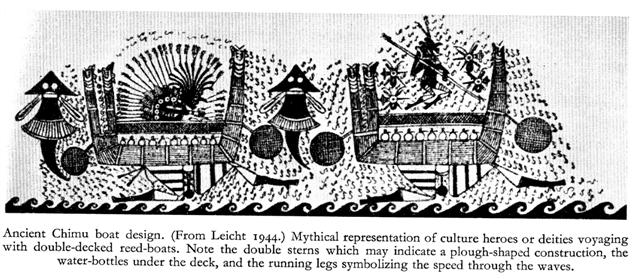

The double tail in GD47 (tôa) must be explained. Were there ever canoes with double tails? Yes, in Heyerdahl 6 we can read that anciently in South America reed canoes with Y-formed tails were used: "... the stoical Peruvian seamen, who were capable of restoring the decreasing buoyancy of their inflated seal-skin bags by blowing them up while sitting on them at sea, would also be capable of repairing their reed-craft while afloat, by exchanging wet reeds in the bottom layers with a dry supply from above the water level. This would only have to be done at intervals of many weeks, and would seem a simple performance since the bow and stern-pieces, to judge from the prehistoric reproductions, were raised suggestively high above the water. These vertical but very light reed-bundles would, therefore, be kept perfectly dry by the combined action of wind and sun, and would give a skilled crew the full opportunity of manipulating the buoyancy of their craft to a considerable degree over a long period of time. The same upturned bow and stern-pieces may even give us a clue to the stability of these long lost reed vessels: they are shown by the Early Chimu artists with a double stern. This, combined with the plain reproduction of a superimposed platform or deck, clearly indicates that we are dealing with some sort of forked or plough-shaped craft, if not directly a double-raft like some New Zealand log-rafts and some of the decked reed-rafts of Lake Titicaca used in historical times.

Although the image is not perfectly clear, I can count to 26 'feathers' in the outer perimeter of the headdress of the 'captain' onboard the left boat. The arrangement among these 'feathers' also suggests a number oriented design (10 + 6 + 10, and several subdivisions obviously meant to describe something). Plough-shaped vessels were not quite unfamiliar even in Polynesian boat-construction at the time of European discoveries. Byron (1826, p. 207) describes a canoe 'of very singular construction' which he observed in the Hervey Group: 'Though double, like the warcanoes of the Sandwich Islands, its form is very different. The prows and waists were two, but the sterns united, so as to form but one, and this stern, curiously carved, was carried up in a curve to the height of six or seven feet above the water's edge.'1 1 The same author also speaks of the deity Rono for whom Captain Cook was mistaken in Hawaii, stating that the last which is recalled of him is that 'he embarked in a triangular boat (piama lau), and sailed to a foreign land.' The prominent Y-shaped stern of ancient reed vessels may thus be the origin of the tôa design. The tôa glyphs in the night have 'open' Y:s. I have earlier translated them as 'open limbs' with spirit-hood status. That would be in harmony with the design being ancient, the time of the spirits. Another idea: New spirits shoot up into the sky at the proper time during the year (by way of reiga) and follow the sun towards the west. They will then turn into stars (hetu'u).

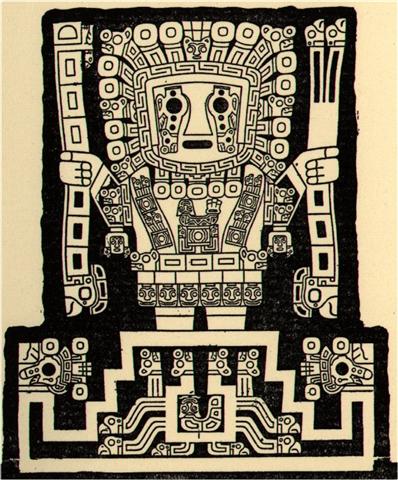

The heavenly bodies (hetu'u) live up in the sky and their fires is what we observe here down below. It may be their camp fires or it may be their eyes, but fire there is. Fire is the opposite of water. Therefore, to raise the bow and sterns means to make them dry. The Y-shape in the 'night' half of the year which we see in the Gateway of the Sun probably also represents the ancient spiritual reed vessel with Y-tail, while the 'day' half of the year has a more modern design:

Possibly we in Ab4-45 and Ab4-46 may interpret the prominent upturned beaks as a sign pointing towards heaven:

In the sky the redfaced (and warrior) Mars seems to be symbolized by tôa, at least in this calendar of the week (in Keiti):

So far I have not discovered any other rongorongo text which has this general design, but in Keiti we have two more examples:

The smith, robbing celestial fire and in his haste to escape later colliding with mother earth (according to Ogotemmêli) with a shock breaking his limbs - that must be Mars, I think. How else may tutu mean a) fire b) stand upright c) to hit, to strike? ... The ground was rapidly approaching. The ancestor was still standing, his arms in front of him and the hammer and anvil hanging across his limbs. The shock of his final impact on the earth when he came to the end of the rainbow, scattered in a cloud of dust the animals, vegetables and men disposed on the steps. When calm was restored, the smith was still on the roof, standing erect facing towards the north, his tools still in the same position. But in the shock of landing the hammer and the anvil had broken his arms and legs at the level of elbows and knees, which he did not have before. He thus acquired the joints proper to the new human form, which was to spread over the earth and to devote itself to toil.' The appearance of GD47 (tôa) in Tuesday, the day of Mars, is evidence for the idea that an ancient double-tailed caone is depicted.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||