|

TRANSLATIONS

I have realized the

necessity to add, in the dictionary item for

manu rere (GD11), a proof that also the

Polynesians regarded Saturn as a 'king':

|

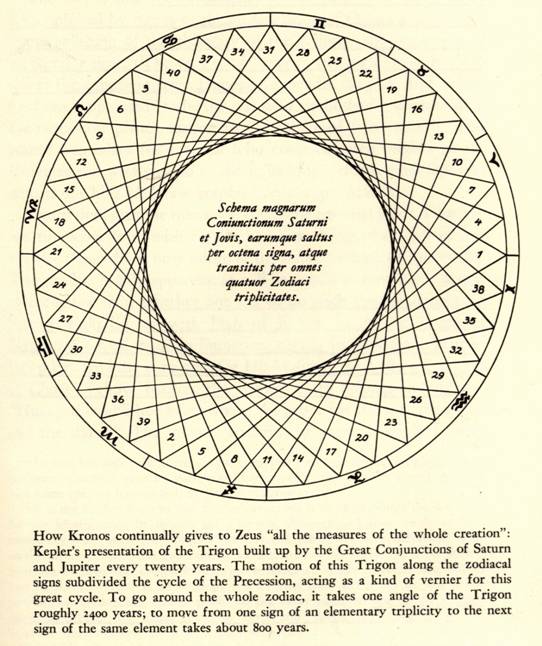

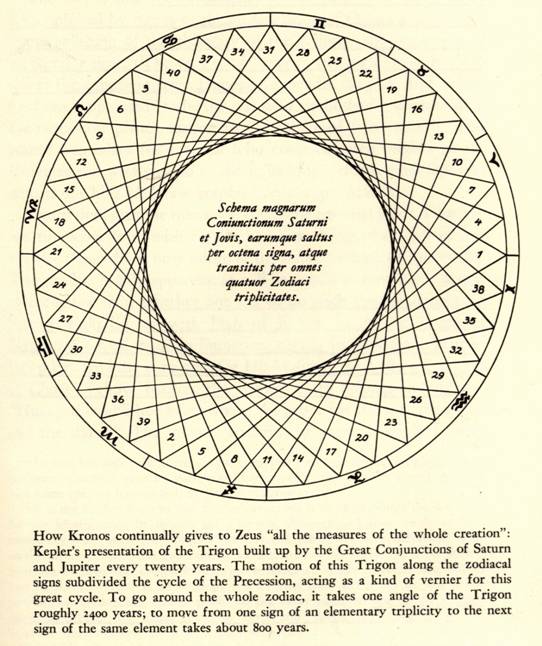

"... Saturn does give the measures:

this is the essential point. How are we to reconcile it with Saturn the First

King, the ruler of the Golden Age who is now asleep at the outer confines of the

world?

The conflict is only apparent, as

will be seen. For now it is essential to recognize that, whether one has to do

with the Mesopotamian Saturn, Enki / Ea, or with Ptah of Egypt, he is the 'Lord

of Measures' - spell it 'me' in Sumerian, 'parshu' in Akkadian, 'maat'

in Egyptian. And the same goes for His Majesty, the Yellow Emperor of China -

yellow, because the element earth belongs to Saturn - 'Huang-ti

established everywhere the order for the sun, the moon and the stars'. The

melody remains the same. It might help to understand the general idea, but

particularly the lucubrations of Proclus, to have a look at the figure drawn by

Kepler, which represents the moving triangle fabricated by 'Great Conjunctions',

that is those of Saturn and Jupiter. One of these points needs roughly 2.400

years to move through the whole zodiac." (Hamlet's Mill)

"Fetu-tea [Pale Star =

Saturn] was the king. He took to wife the dome of the sky, Te-Tapoi-o-te-ra'i,

and begat stars that shine (hitihiti) and obscure, the host of twinkling

stars, fetu-amoamo, and the phosphorescent stars, te fetu-pura-noa.

There followed the star-fishes, Maa-atai, and two trigger-fishes that eat

mist and dwell in vacant spots in the Milky Way, the Vai-ora or

Living-water of Tane. The handsome shark Fa'a-rava-i-te-ra'i,

Sky-shade, is there in his pool and close by is Pirae-tea, White

Sea-swallow (Deneb in Cygnus) in the Living-waters of Tane." (Makemson) |

Then, why is there

a double-rimmed vai glyph in Sunday

according to the P text:

|

By now it must be clear that GD16 (vai)

is a symbol for the sun.

There remains, though, at least one

question to be answered: Why is

there a single oval in Hb9-18

and a double in Pb10-30?

|

I think there is a

connection between the double-rimmed vai

in P and the eye inscribed in manu rere.

Both phenomena are meant to underline that the

eye of the sun is meant.

Manu rere is

the sun and vai is the sun, although in

two different aspects. Possibly vai

glyphs are meant to illustrate Tama-Nui-Te-Ra:

'...

It

was during this struggle with the sun that his

second name was learned by man. At the height of

his agony the sun cried out: 'Why am I treated

by you in this way? Do you know what it is you

are doing. O you men? Why do you wish to kill

Tama nui te ra?' This was his name, meaning

Great Son of the Day, which was never known

before ...'

Tama-iti may

be the sun child and Tama-nui the grownup

sun:

|

|

|

Ba1-13 |

GD16 |

|

tamaiti |

tamanui |

Polynesian

children were swaddled, which may explain the

form of tamaiti glyphs (a form which I

once thought meant pregnancy):

|

... At the start of

the X-area we do not find henua

(GD37) but niu (GD18),

although much points to the idea

that these niu

glyphs are standing at the beginning of new year:

|

|

|

|

Aa1-13 |

Pa5-67 |

How may that be

explained? Is a picture of a tree

too trivial? The halo around the

head of a holy 'person' would be

difficult to picture in a

rongorongo glyph (because such

glyphs show only outlines).

Radiating light in all directions

would be easier to draw (as in niu).

The picture is from Wikipedia:

'Madonna and Child' by Ambrogio

Lorenzetti. I searched for

'swaddling', with the idea that I

would find some picture of how

Polynesians swaddled their newborn

babies. However I did not find any

such information.

Newborn babies do not show their

arms and legs, because they have

been swaddled. That could explain

the shape of Pa5-70 (and similar

glyphs):

"The child has hardly left the

mother's womb, it has hardly begun

to move and stretch its limbs, when

it is given new bonds. It is wrapped

in swaddling bands, laid down with

its head fixed, its legs stretched

out, and its arms by its sides; it

is wound round with linen and

bandages of all sorts so that it

cannot move …

Whence comes this unreasonable

custom? From an unnatural practice.

Since mothers despise their primary

duty and do not wish to nurse their

own children, they have had to

entrust them to mercenary women.

These women thus become mothers to a

stranger's children, who by nature

mean so little to them that they

seek only to spare themselves

trouble. A child unswaddled would

need constant watching; well

swaddled it is cast into a corner

and its cries are ignored …

It is claimed that infants left free

would assume faulty positions and

make movements which might injure

the proper development of their

limbs. This is one of the vain

rationalizations of our false wisdom

which experience has never

confirmed. Out of the multitude of

children who grow up with the full

use of their limbs among nations

wiser than ourselves, you never find

one who hurts himself or maims

himself; their movements are too

feeble to be dangerous, and when

they assume an injurious position,

pain warns them to change it."

(Wikipedia citing Jean Jacques

Rousseau - Emile: Or, On Education,

1762.) |

Before entering on

an investigation of the GD17 glyphs, I had

better here present what I have recently written

in the dictionary:

|

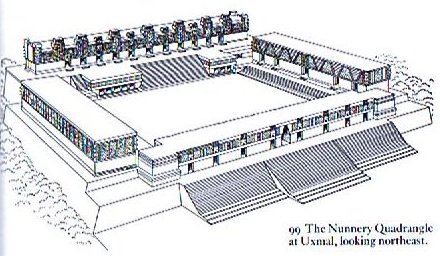

A few preliminary remarks and

imaginations:

1.

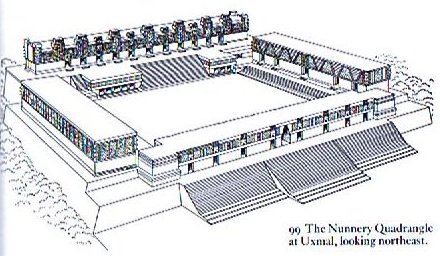

"An iconographic study by Jeff

Kowalski suggests a cosmological

layout for the Nunnery. The higher

placement of the North Building,

with its 13 exterior doorways

(reflecting the 13 layers of

heaven), and the celestial serpents

surmounting the huts identify it

with the celestial sphere.

The iconography of the West

Building, with 7 exterior doorways

(7 is the mystic number of the

earth's surface), and figures of

Pawahtun - the earth god as a

turtle - indicate this to be the

Middleworld, the place of the sun's

descent into the Underworld.

The East Building has mosaic

elements reflecting the old war cult

of Teotihuacan,

where tradition had it that the sun

was born; thus, this may also be

Middleworld, the place of the rising

sun. Finally, the South Building has

9 exterior doorways (the Underworld

or Xibalba

had 9 layers), and has the lowest

placement in the compex; it thus

seems to be associated with death

and the nether regions." (The Maya)

While we modern people in the

western societies probably think of

the turtle as the emblem of slow

motion, ancient peoples had other

key associations. To begin with, the

turtle is neither flying high like

the birds nor swimming far down in

the sea like the fishes. A turtle is

living at the surface of the sea or

crawling on land, i.e. in the

middle

world. The sky roof contains air,

the bowl of the sea has water and in

the middle is the earth we live in.

Clearly the carapace of the

turtle has an upper shell and a

lower shell and in the middle we

find the living creature. |

|

"A

very detailed myth comes from the

island of Nauru. In the

beginning there was nothing but the

sea, and above soared the

Old-Spider. One day the Old-Spider

found a giant clam, took it up, and

tried to find if this object had any

opening, but could find none. She

tapped on it, and as it sounded

hollow, she decided it was empty.

By

repeating a charm, she opened the

two shells and slipped inside. She

could see nothing, because the sun

and the moon did not then exist; and

then, she could not stand up because

there was not enough room in the

shellfish. Constantly hunting about

she at last found a snail. To endow

it with power she placed it under

her arm, lay down and slept for

three days. Then she let it free,

and still hunting about she found

another snail bigger than the first

one, and treated it in the same way.

Then she said to the first snail:

'Can you open this room a little, so

that we can sit down?' The snail

said it could, and opened the shell

a little.

Old-Spider then took the snail,

placed it in the west of the shell,

and made it into the moon. Then

there was a little light, which

allowed Old-Spider to see a big

worm. At her request he opened the

shell a little wider, and from the

body of the worm flowed a salted

sweat which collected in the lower

half-shell and became the sea. Then

he raised the upper half-shell very

high, and it became the sky. Rigi,

the worm, exhausted by this great

effort, then died. Old-Spider then

made the sun from the second snail,

and placed it beside the lower

half-shell, which became the earth."

(New Larousse Encyclopedia of

Mythology) |

|

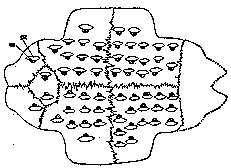

2. The ancient Chinese

used to drill holes in turtle shells

and then place them in the

fire to see what cracks

developed. The cracks foretold the

future:

(Ref. Lindqvist)

Turtles are associated with earth

and earth is resistant to fire. The

Polynesians had earth-ovens (umu)

in which food was prepared. The

heavenly firedrill had a turtle at

the bottom to isolate the earth from

a general conflagration when at new

year a fire must be ignited.

(Ref. Hamlet's Mill)

|

"... the tortoise cannot

be burnt ... a

characteristic which is

confirmed objectively by

ethnography, since the

wolf's trick [in M192]

of trying to cook the

tortoise while it was

lying on its back is

based on a method which

may seem barbarous but

is still current in

central Brazil: the

tortoise is so difficult

to kill that the

peasants cook it alive

among the hot wood

cinders, with its own

shell acting as the

cooking-dish; the

process may last several

hours, because the poor

beast takes so long to

die ..." (From Honey to

Ashes) |

|

|

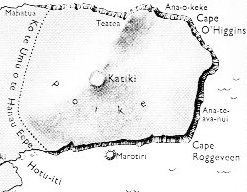

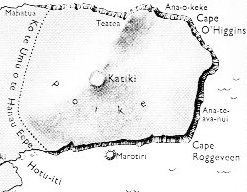

3. On Easter Island the

sacred geography has

Haga Hônu on one side of

Poike and Haga Takaure on

the other:

.jpg)

(Ref. Métraux)

Growing sun advances from the

three little islands outside the

south-western point of Orongo

up to Poike (corresponding to

noon and midsummer) at the eastern

extreme of the island, then

descending sun moves along the

northern coast, arriving at Haga

Hônu approximately at autumn

equinox (sundown). The point where

sun reaches earth does not catch

fire because Hônu is there

protecting us.

The kuhane of Hau

Maka described the path for

him in his dream. |

|

"Hau Maka had a dream. The

dream soul of Hau Maka moved

in the direction of the sun (i.e.,

toward the East). When, through the

power of her mana, the dream

soul had reached seven lands, she

rested there and looked around

carefully. The dream soul of Hau

Maka said the following: 'As

yet, the land that stays in the dim

twilight during the fast journey has

not been reached.'

The dream soul of Hau Maka

countinued her journey and, thanks

to her mana, reached another

land. She descended on one of the

small islets (off) the coast). The

dream soul of Hau Maka looked

around and said: 'These are his

three young men.' She named the

three islets 'the handsome youths of

Te Taanga, who are

standing in the water'.

The dream soul of Hau Maka

continued her journey and went

ashore on the (actual Easter)

Island. The dream soul saw the fish

Mahore, who was in a (water)

hole to spawn (?), and she named the

place 'Pu Mahore A Hau Maka O

Hiva'.

The dream soul climbed up and

reached the rim of the crater. As

soon as the dream soul looked into

the crater, she felt a gentle breeze

coming toward her. She named the

place 'Poko Uri A Hau Maka O Hiva'.

The dream soul continued her search

for a residence for King Matua.

The dream soul of Hau Maka

reached (the smaller crater)

Manavai and named the place 'Te

Manavai A Hau Maka O Hiva'. The

dream soul went on and reached Te

Kiore Uri. She named the place 'Te

Kiore Uri A Hau Maka O Hiva'.

The dream soul went on and came to

Te Piringa Aniva. She named

the place 'Te Piringa Aniva A Hau

Maka O Hiva'. Again the dream

soul went on her way and reached

Te Pei. She named the place 'Te

Pei A Hau Maka O Hiva'. The

dream soul went on and came to Te

Pou. She named the place 'Te

Pou A Hau Maka O Hiva'. The

dream soul went on and came to

Hua Reva. She named the place 'Hua

Reva A Hau Maka O Hiva'. The

dream soul went on and came to

Akahanga. She named the place 'Akahanga

A Hau Maka O Hiva'.

The dream soul went on. She was

careless (?) and broke the kohe

plant with her feet. She named the

place 'Hatinga Te Koe A Hau Maka

O Hiva'.

The

dream soul went on and came to

Roto Ire Are. She gave the name

'Roto Ire Are A Hau Maka O Hiva'.

The dream soul went on and came to

Tama. She named the place 'Tama',

an evil fish (he ika kino)

with a very long nose (he ihu

roroa).

The dream soul went on and came to

One Tea. She named the place

'One Tea A Hau Maka O Hiva'.

She went on and reached Hanga

Takaure. She named the place 'Hanga

Takaure A Hau Maka O Hiva'. The

dream soul moved upward and came to

(the elevation) of Poike. She

named the place 'Poike A Hau Maka

O Hiva'. The dream soul

continued to ascend and came to the

top of the mountain, to Pua

Katiki. She named the place 'Pua

Katiki A Hau Maka O Hiva'.

Everywhere the dream soul looked

around for a residence for the king.

The dream soul went to Maunga

Teatea and gave him the name 'Maunga

Teatea A Hau Maka O Hiva'. The

dream soul of Hau Maka looked

around. From Maunga Teatea

she looked to Rangi Meamea

(i.e., Ovahe).

The dream soul spoke the following:

'There it is - ho! - the place - ho!

- for the king - ho! - to live

(there in the future), for this is

(indeed) Rangi Meamea.' The

dream soul descended and came to

Mahatua. She named the place 'Mahatua

A Hau Maka O Hiva'. The dream

soul continued to look around for a

residence for the king. Having

reached Taharoa she named the

place 'Taharoa A Hau Maka O Hiva'.

The dream soul moved along and

reached Hanga Hoonu. She

named the place 'Hanga Hoonu A

Hau Maka O Hiva'.

The dream soul came to Rangi

Meamea and looked around

searchingly. The dream soul spoke:

'Here at last is level land where

the king can live.' She named the

place 'Rangi Meamea A Hau Maka O

Hiva'. The mountain she named 'Peke

Tau O Hiti A Hau Maka O Hiva'.

The dream soul moved along a curve

from Peke Tau O Hiti to the

mountain Hau Epa, which she

named 'Maunga Hau Epa A Hau Maka

O Hiva'.

The dream soul stepped forth lightly

and reached Papa O Pea. She

carefully looked around for a place

where the king could settle down

after his arrival and gather his

people around (? hakaheuru).

Having assembled his people (?) and

having come down, he would then go

from Oromanga to Papa O

Pea, so went the speech of the

dream soul. She named the place 'Papa

O Pea A Hau Maka O Hiva'.

She then hastened her steps toward

Ahu Akapu. There she looked

again for a residence of the king.

Again the dream soul of Hau Maka

spoke: 'May the king assemble his

people (?) and may he come in the

midst of his people from Oromanga

to Papa O Pea. When the king

of Papa O Pea has assembled

his people (?) and has come to this

place, he reaches Aha Akapu.

To stay there, to remain (for the

rest of his life) at Ahu Akapu,

the king will abdicate (?) as soon

as he has become an old man'. She

named the place 'Ahu Akapu A Hau

Maka O Hiva'. The (entire) land

she named 'Te Pito O Te Kainga A

Hau Maka O Hiva'.

The dream soul turned around and

hurried back to Hiva, to its

(Home)land, to Maori. She

slipped into the (sleeping) body of

Hau Maka, and the body of

Hau Maka awakened. He arouse and

said full of amazement 'Ah' and

thought about the dream ..."

(Barthel 2, maps from Heyerdahl 4) |

|

In the Mamari

calendar for the month there are 8 periods of different lengths. The

last of the periods has only 2 nights (a night is symbolized by a moon sickle):

|

|

|

|

|

|

Ca8-27 |

Ca8-28 |

Ca8-29 |

Ca9-1 |

Ca9-2 |

Ca8-27 is a peculiar hônu glyph with a long 'peg' at

bottom and it presumably illustrates how at new moon a new fire is being alighted,

possibly by fire drilling (which is not the usual Polynesian

method to light fires). In Ca5-17 a similar hônu ignites

new sun fire in midwinter:

The back-to-back persons (Ca8-28--29 respectively Ca5-18--19)

are the old and new periods, i.e. the Janus concept - called

Takurua in

Polynesian.

|

We should notice how the position of hônu

immediately before takurua takes on a more

profound meaning when we consider the numerical

facts: Ca9-1--2 are the two first nights of the new

month and the creator of the text has ingeniously

arranged them to also initiate a new line (Ca9).

Ca8-28 is the last night of the old month in which

moon is visible, while in Ca8-29 the moon is dark.

Likewise, Ca5-18 presumably signifies the last time

sun is present, while Ca5-19 is a vero time.

360 / 2 = 180 measures a 'year'.

Hônu, therefore, is present while the old

'light' still is 'alive'. |

|

|

"At the risk of invoking the

criticism, 'Astronomers rush

in where philologists fear

to tread', I should like to

suggest that Taku-rua

corresponds with the

two-headed Roman god Janus

who, on the first of

January, looks back upon the

old year with one head and

forward to the new year with

the other, and who is god of

the threshold of the home as

well as of the year...

There is probably a play on

words in takurua - it

has been said that

Polynesian phrases usually

invoke a double meaning, a

common and an esoteric one.

Taku means 'slow',

the 'back' of anything,

'rim' and 'command'. Rua

is a 'pit', 'two' or

'double'. Hence takurua

has been translated 'double

command', 'double rim', and

'rim of the pit', by

different authorities.

Taku-pae is the Maori

word for 'threshold'...

Several Tuamotuan and

Society Islands planet names

begin with the word

Takurua or Ta'urua

which Henry translated Great

Festivity and which is the

name for the bright star

Sirius in both New Zealand

and Hawaii.

The planet names, therefore,

represent the final stage in

the evolution of takurua

which was probably first

applied to the winter

solstice, then to Sirius

which is the most

conspicious object in the

evening sky of December and

January, and was then

finally employed for the

brilliant and conspicious

planets which outshone even

the brightest star Sirius.

From its association with

the ceremonies of the new

year and the winter

solstice, takurua

also aquired the meaning

'holiday' or 'festivity'."

(Makemson) |

|

In the G calendar

the situation seems

to be different

(according to how we

so far have

interpreted the

calendars of E and

G), because the

hônu arrive at

autumn equinox (and

not at midsummer):

|

|

In

ancient Egypt a similar perception was at work, although the sky

dome was female:

(Ref. Wilkinson and Lockyer)

The

goddess Nut (Nu-t where final t indicates

female) is depicted with stars spangled over her body. The canoe of

the sun is during the night travelling above her body from the feet

to her hands. Feet and hands are resting on the ground.

Whereas in rongorongo the sky dome was depicted as the body

of a male (because it illustrates the day sky), in Egypt the sky

dome was depicted as the body of a female because Nut means

night. Night is female and day is male. |

|

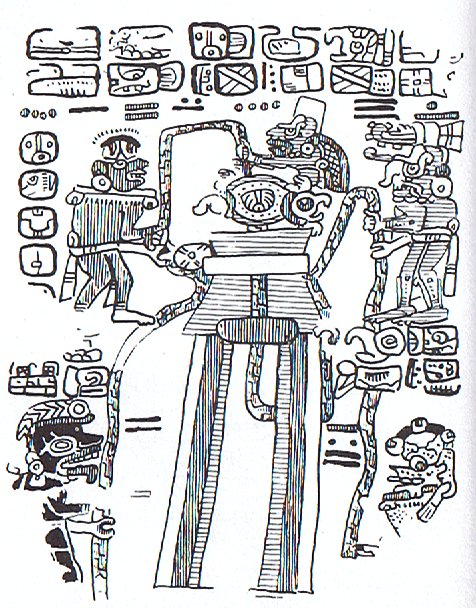

We can identify the 2nd quarter 'person' with the 'worm' Rigi:

... By repeating a charm, she opened the two

shells and slipped inside. She could see nothing, because the

sun and the moon did not then exist; and then, she could not

stand up because there was not enough room in the shellfish.

Constantly hunting about she at last found a snail. To endow it

with power she placed it under her arm, lay down and slept for

three days. Then she let it free, and still hunting about she

found another snail bigger than the first one, and treated it in

the same way. Then she said to the first snail: 'Can you open

this room a little, so that we can sit down?' The snail said it

could, and opened the shell a little.

Old-Spider then took the snail, placed it in the

west of the shell, and made it into the moon. Then there was a

little light, which allowed Old-Spider to see a big worm. At her

request he opened the shell a little wider, and from the body of

the worm flowed a salted sweat which collected in the lower

half-shell and became the sea. Then he raised the upper

half-shell very high, and it became the sky. Rigi, the

worm, exhausted by this great effort, then died. Old-Spider then

made the sun from the second snail, and placed it beside the

lower half-shell, which became the earth ...

Careful reading leads to conclusions:

There were two

snails, a little one and a bigger one. The first, the little

one, became the moon and her location was in the west. The

bigger snail became the sun and his location was in the east.

Both snails first

needed power, and that was accomplished by 3 days in the armpit

while Old Spider lay down. At winter solstice movement stops, a

time for lying down. The 3 nights (rather than days) of complete

darkness are those between 365 and 362 (= 180 + 182) when 'gods

are born'. The armpit is a center for re-creation.

Rigi is

neither of the two snails but another being, a very powerful

'worm'. Exhausted he dies at summer solstice. In his stead the

salty sea emerged and sun is not placed in the east until the

worm has gone.

Rigi is

obviously a wordplay on ragi (sky). |

|

In the G

calendar it

was possible

to count

glyphs in

order to

arrive at a

hidden

structure

beneath the

periods.

Likewise, it

is possible

to count

glyphs in

the E

calendar and

thereby find

out what

structure

will be

revealed.

18 periods

describe the

central part

to the E

calendar.

The 1st

period is

exceptional

and outside

the central

part, which

has 2 * 54 =

108

glyphs, a

fascinating

number.

| 2 - 4 |

12 |

54 |

| spring: |

| 5 - 8 |

28 |

42 |

| 9 - 10 |

14 |

| summer: |

| 11 - 13 |

20 |

30 |

54 |

| 14 - 16 |

10 |

| autumn: |

| 17 - 19 |

24 |

42

(periods 5-10) is already understood as an important number ('the

7th flame of

the sun').

36 can be reconstructed as the number of glyphs in periods

2-4 plus those in periods 17-19.

It

means that 108 = 30 + 36 + 42. The regular year is divided in 3

parts of different lengths, although one part (30) is divided

unequally with ⅓ in late winter (before spring) and ⅔ in early

winter (after autumn). And then we have not yet considered the 1st and

the last

5 periods (20-24). |

|

"... It

is known

that in

the

final

battle

of the

gods,

the

massed

legions

on the

side of

'order'

are the

dead

warriors,

the

'Einherier'

who once

fell in

combat

on earth

and who

have

been

transferred

by the

Valkyries

to

reside

with

Odin in

Valhalla

- a

theme

much

rehearsed

in

heroic

poetry.

On the

last

day,

they

issue

forth to

battle

in

martial

array.

Says

Grimnismal

(23):

'Five

hundred

gates

and

forty

more -

are in

the

mighty

building

of

Walhalla

- eight

hundred

'Einherier'

come out

of each

one gate

- on the

time

they go

out on

defence

against

the Wolf.'

That

makes

432,000

in all,

a number

of

significance

from of

old.

This

number

must

have had

a very

ancient

meaning,

for it

is also

the

number

of

syllables

in the

Rigveda.

But it

goes

back to

the

basic

figure

10,800,

the

number

of

stanzas

in the

Rigveda

(40

syllables

to a

stanza)

which,

together

with

108,

occurs

insistently

in

Indian

tradition,

10,800

is also

the

number

which

has been

given by

Heraclitus

for the

duration

of the

Aiōn,

according

to

Censorinus

(De

die

natali,

18),

whereas

Berossos

made the

Babylonian

Great

Year to

last

432,000

years.

Again,

10,800

is the

number

of

bricks

of the

Indian

fire-altar

(Agnicayana).32

32

See J.

Filliozat,

'L'Indie

et les

échanges

scientifiques

dans

l'antiquité',

Cahiers

d'histoire

mondiale

1

(1953),

pp. 358f.

'To

quibble

away

such a

coincidence',

remarks

Schröder,

'or to

ascribe

it to

chance,

is in my

opinion

to drive

skepticism

beyond

its

limits.'33

33

F. R.

Schröder,

Altgermanischer

Kulturprobleme

(1929),

pp. 80f.

Shall

one add

Angkor

to the

list? It

has five

gates,

and to

each of

them

leads a

road,

bridging

over

that

water

ditch

which

surrounds

the

whole

place.

Each of

these

roads is

bordered

by a row

of huge

stone

figures,

108 per

avenue,

54 on

each

side,

altogether

540

statues

of Deva

and

Asura,

and each

row

carries

a huge

Naga

serpent

with

nine

heads.

Only,

they do

not

'carry'

that

serpent,

they are

shown to

'pull'

it,

which

indicates

that

these

540

statues

are

churning

the

Milky

Ocean,

represented

(poorly,

indeed)

by the

water

ditch,34

using

Mount

Mandara

as a

churning

staff,

and

Vasuki,

the

prince

of the

Nagas,

as their

drilling

rope.

34

R. von

Heine-Geldern,

'Weltbild

und

Bauform

in

Südostasien',

in

Wiener

Beiträge

zur

Kunst-

und

Kulturgeschichte

4

(1910),

p. 15.

(Just to

prevent

misunderstanding:

Vasuki

had been

asked

before,

and had

agreeably

consented,

and so

had

Vishnu's

tortoise

avatar,

who was

going to

serve as

the

fixed

base for

that

'incomparably

mighty

churn',

and even

the

Milky

Ocean

itself

had made

it clear

that it

was

willing

to be

churned.)

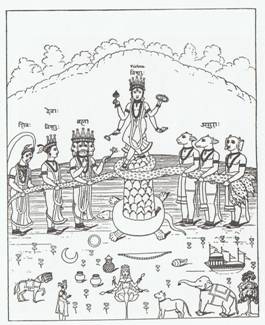

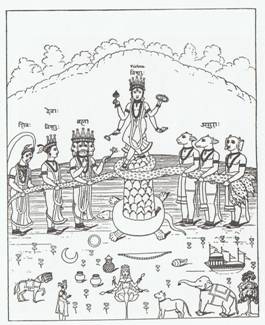

The

'incomparably

mighty

churn'

of the

Sea of

Milk, as

described

in the

Mahabharata

and

Ramayana.

The

heads of

the

deities

on the

right

are the

Asura,

with

unmistakable

'Typhonian'

characteristics.

They

stand

for the

same

power as

the

Titans,

the

Turanians,

and the

people

of

Untamo,

is

short,

the

'family'

of the

bad

uncle,

among

whom

Seth is

the

oldest

representative,

pitted

against

Horus,

the

avenger

of his

father

Osiris.

The

simplified

version

of the

Amritamanthana

(or

Churning

of the

Milky

Ocean)

still

shows

Mount

Mandara

used as

a pivot

or

churning

stick,

resting

on the

tortoise.

And

here,

also,

the head

on the

right

has

'Typhonian'

features.

The

whole of

Angkor

thus

turns

out to

be a

colossal

model

set up

for

'alternative

motion'

with

true

Hindu

fantasy

and

incongruousness

to

counter

the idea

of a

continuous

one-way

Precession

from

west to

east."

(Hamlet's

Mill) |

|

108

can be read as 30 + 36 + 42 = (5 + 6 + 7) * 6. Counting also the

jokers there are 2 * 54 = 108 cards in a double deck.

In

the regular pentagon the internal angles are 180 * (5 - 2) / 5 =

108º.

However, in the E calendar 54 probably first of all represents 3 *

18 (and 108 = 6 * 18).

South

of the equator the summer half of the year is ca 180 days, and

combining 18 with the fundamental solar number 6 we reach 108. Half

that number comes before the midpoint and the other half after.

The

midpoint

lies

between

periods

10

and

11,

exactly

as

we

earlier

have

discovered

by

way

of

henua

ora

in

the

10th

and

vero

in

the

11th

period.

Disregarding

the

1st

period

there

are

9

periods

up

to

the

midpoint

and

9

after.

The

autumn

vero

is

located

in

the

19th

period,

i.e.

in

the

last

of

the

summer

periods

(according

to

the

structure

observed

in

the

number

of

glyphs).

The

summer

vero

(11th

period)

inaugurates

the

2nd

half

of

the

year

and

the

3rd

quarter,

while

the

autumn

vero

(19th

period)

ends

summer

and

the

3rd

quarter.

During

9

periods

with

54

glyphs

sun

advances

and

during

9

periods

with

54

glyphs

sun

declines.

These

two

phases

have

each

6 *

9 =

54

glyphs.

Each

glyph

therefore

may

correspond

to a

duration

of

3⅓

days

(180/54

=

3⅓).

To

avoid

fractions

it

is

necessary

to

count

in

durations

of

at

least

10

days.

Each

half-year

has

18 *

10 =

9 *

20 =

180

days,

but

54 =

3 *

18

suggests

that

each

half-year

is

divided

in 3

* 60

days,

3

periods

which

each

is

divided

in 3

lesser

periods

à 20

days. |

|

Comparing with the glyph number structure in G we find nothing there which contradicts the assumed 3 periods à (20+20+20) days in each half-year:

| period no. |

number of glyphs |

| 1, 2, 3 |

19 |

19 |

| 4, 5, 6 |

8 |

27 |

| 7, 8, 9 |

8 |

35 |

| 10, 11, 12 |

7 |

42 |

| 13, 14, 15 |

12 |

54 |

| 16, 17, 18 |

16 |

70 |

The midpoint is located between periods 9 and 10, not between 10 and 11 as in E. But that, we know, is due to the 1st period in E being counted although it does not belong to the regular year.

The autumn vero (period 19 in G) is, however, outside the regular year (not ending summer as in E).

In G

35 glyphs seems to correspond to 90 days, which may be expressed as 7

(after division by 5) in relation to 18 (after division by 5). 7

glyphs will then correspond to 18 days and 70 (= 10 * 7) glyphs

equal 180

days. Sun seems to have 10 periods à 7 glyphs to live, 5 before the midpoint

and 5 after.

It is

as if sun has 'weeks', though only 10 such. |

|

If we now consider the 6 periods which in E lie outside the regular year, we find the structure to be:

| 20 |

4 |

15 |

61 |

| 21 |

3 |

| 22 |

4 |

| 23 |

4 |

| 24 |

26 |

| 1 |

20 |

26 glyphs are in the last period and 20 in the first period. These two numbers are highly significant. For instance, is the number of glyphs in Tahua (1,334) divided in two groups determined by them: 26 * 29 + 20 * 29 = 754 + 580. Presumably they signify the darkest time of the year, the time corresponding to new moon.

15 is related to the moon, viz. the number of nights up to and including full moon. 3 (an odd number) is necessary to reach 15. 3 has also the role of covering the time between 365 and (180 + 182) days, given that the summer 'year' has 12 * 15 = 180 days and the winter 'year' 13 * 14 = 182 days. Purely speculation, of course.

61 it is needed to reach 13 * 13 = 169 glyphs for the whole calendar (61 + 108 = 169). 61 also happens to be related to 10 and 6 in a curious way.

15 is the moon number equivalent to the sun number 10 - the time at which the measure is full and the waxing phase has ended. That explains why in the 10th period of the calendar we have henua ora (the sun harbour). |

| In Chinese checkers the board is built up like a 6-pointed star:

Each of the triangular 'flames' has 10 holes (= 1 + 2 + 3 + 4). Together there are 6 * 10 = 60 holes around the central hexagon.

The central hexagon has 61 holes, astoundingly not 60.

In a way it is as if the creator of the E calendar had seen this picture. But Chinese checkers was not invented until much later.

The 6 'flames' are similar to the 6 times 60 days necessary to reach 360 days for a year, while 61 is the mirror image with one additional hole in the center, the germ of next year carried in the middle as if the embryo to a new ‘world’. |

|

20

glyphs in the 1st period in a way predicts how after 10 periods sun

will reach 'harbour' (henua ora). Maybe 2 glyphs corresponds

to 1 period? That is probably not so, because 20 presumably

represents 20 periods - 10 up to the midpoint and 10 after the

midpoint. Or to be more precise: the 10th period has passed the

midpoint and the 20th period has passed the end of the next half.

10 means one more than full, which of course is true if we regard 9 as the measure for full - there are no higher digits. 20 means that the limit has passed once more, and as there are two 'years' in a year 20 is the proper symbol.

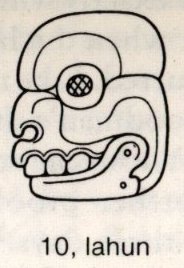

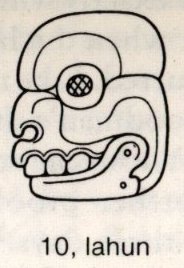

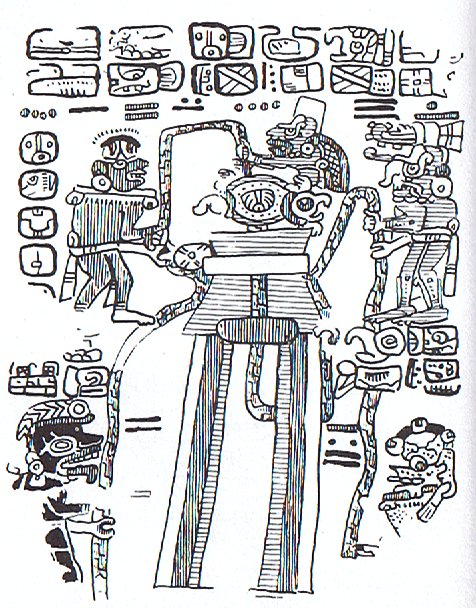

The Mayan number symbol for 10 has a fleshless jawbone - a sign of death:

|

|

Possibly 26 in the last period tells about how during a year there are 26 fortnights (14 * 26 = 364). With 20 in the first period representing 20 * 18 (= 360) solar days, 26 may mean 364 lunar nights.

Counting would proceed upwards with waxing sun to the 10th period. Beyond that comes the time of the moon and sun wanes.

Vero in the 11th period means that sun is no more. Vero in the 19th period has a sign of the moon:

It means that the moon

has no more time. With the 20th period darkness arrives.

Moon will therefore have an equal amount of glyphs as the sun:

| sun |

2 - 4 |

12 |

54 |

| 5 - 8 |

28 |

42 |

| 9 - 10 |

14 |

| summer solstice |

| moon |

11 - 13 |

20 |

30 |

54 |

| 14 - 16 |

10 |

| 17 - 19 |

24 |

|

|

We have seen two different hônu designs, what may be called the 'ignition turtle' and the 'quenching turtle' (water quenches fire), here exemplified from G:

|

|

| Ga3-12 |

Ga5-14 |

At new year, in ancient times all over the world, when a new fire was to be ignited - magically inducing the winter solstice sun to come alive again - the old fire was first 'quenched'. The Maya Indians offer a good example.

On Easter Island there is a story about how the explorers ignited a new fire at Haga Hônu on the north coast. According to the sacred geography of the island Haga Hônu lies at the beginning of autumn (fall). After sun has risen by way of the south coast up to Poike (maximum) he descends along the north coast.

Logically, if the old sun dies at autumn equinox it must also be the time for a new fire. The new year may therefore be regarded as beginning with autumn equinox.

Fires function as a way to contact the gods high above in heaven and fires were used at all crucial times of the year. Therefore, to light a fire does not necessarily imply that a new year is inaugurated, only that a major new period is beginning. |

|

"[Sahagun:] ... When it was evident that the years lay ready to burst into life, everyone took hold of them, so that once more would start forth - once again - another (period of) fifty-two years.

Then (the two cycles) might proceed to reach one hundred and four years. It was called 'One Age' when twice they had made the round, when twice the times of binding the years had come together.

Behold what was done when the years were bound - when was reached the time when they were to draw the new fire, when now its count was accomplished. First they put out fires everywhere in the country round. And the statues, hewn in either wood or stone, kept in each man's home and regarded as gods, were all cast into the water.

Also (were) these (cast away) - the pestles and the (three) hearth stones (upon which the cooking pots rested); and everywhere there was much sweeping - there was sweeping very clear. Rubbish was thrown out; none lay in any of the houses." (Skywatchers) |

|

"... Again they went on and reached Hanga Hoonu. They saw it, looked around, and gave the name 'Hanga Hoonu A Hau Maka'. On the same day, when they had reached the Bay of Turtles, they made camp and rested. They all saw the fish that were there, that were present in large numbers - Ah!

Then they all went into the water, moved toward the shore, and threw the fish (with their hands) onto the dry land. There were great numbers (? ka-mea-ro) of fish. There were tutuhi, paparava, and tahe mata pukupuku. Those were the three kinds of fish.

After they had thrown the fish on the beach, Ira said, 'Make a fire and prepare the fish!' When he saw that there was no fire, Ira said, 'One of you go and bring the fire from Hanga Te Pau!' One of the young men went to the fire, took the fire and provisions (from the boat), turned around, and went back to Hanga Hoonu. When he arrived there, he sat down. They prepared the fish in the fire on the flat rocks, cooked them, and ate until they were completely satisfied. Then they gave the name 'The rock, where (the fish) were prepared in the fire with makoi (fruit of Thespesia populnea?) belongs to Ira' (Te Papa Tunu Makoi A Ira). They remained in Hanga Hoonu for five days ..." (Barthel 2) |

|

"... Whatever may have been the reason for the preëminence of the Pleiades cluster - and it was probably a combination of several reasons - it is certain that when men became increasingly alert ot the annual cycles of celestial phenomena, the changing altitudes and azimuths of the Sun, the lengthening and shortening of days and the corresponding variation in temperature, the slow march of the constellations across the sky, and realized the need of choosing a day on which to begin the yearly cycle of the calendar, they turned to the Pleiades for guidance.

Undoubtedly the Polynesians carried the Pleiades year with them into the Pacific from the ancient homeland ... With but few exceptions they continued to date the annual cycle from the rising of these stars until modern times.

In the Hawaiian, Samoan, Tongan, Society, Marquesan, and some other islands the new year began in late November or early December with the first new Moon after the first appearance of the Pleiades in the eastern sky in the evening twilight.

Notable exceptions to the general rule are found in Pukapuka and among certain tribes of New Zealand where the new year was inaugurated by the first new Moon after the Pleiades appeared on the eastern horizon just before sunrise in June. Traces of an ancient year beginning in May have been noted in the Society Islands, but there is some uncertainty about the beginning of the year in native annals generally, at least as reported by missionaries and others, due perhaps to the desire to make the Polynesian months coincide with the stated months of the modern calendar.

In view of the almost universal prevalence of the Pleiades year throughout the Polynesian area it is surprising to find that in the South Island and certain parts of the North Island of New Zealand and in the neighboring Chatham Islands, the year began with the new Moon after the yearly morning [heliacal] rising, not of the Pleiades, but of the star Rigel in Orion. Such an important difference can be explained only on the assumption that the very first settlers ... brought the Rigel year with them ... some other land 10° south of the equator where Rigel acquired at the same time its synonymity with the zenith.

Colonists who arrived in New Zealand from Central Polynesia during the Middle Ages and intermarried with the tangata whenua, 'people of the land', found themselves between the horns of a calendrical dilemma. They must either convert the aborigines to the Pleiades year beginning in November-December or themselves adopt the Rigel year [together with heliacal rising observations] and bring down the wrath of their ancestors on their own heads.

That there resulted a long and passionate struggle on the part of both the invaders and the invaded to retain their own the integrity of the sacred year of their traditions can hardly by doubted. The outcome of the conflict proved that the institution of the land was too firmly established to be changed. While some tribes retained the Rigel year in its entirety others effected a compromise by retaining the Pleiades year but commencing it in June ..." (Makemson) |

|

The modern calendar of Easter Island has two autumn months Vaitu nui (April) and Vaitu poru (May). Equally, there are two early spring months with similar names: Hora iti (August) and Hora nui (September). Probably there once were only 10 months and 12 names was introduced by splitting up the old months Vaitu and Hora.

The sense in Vaitu, I guess, is 'water' (vai) at the backside (tu'a). The old name may have been Vaitu'a, '(the) water at the backside (of the) year'. The front (ra'e) side will then be the Hora side, the time when sun is advancing upwards.

The sea turtle naturally will be associated with the watery season. Its resistance to fire is an additional factor which puts the turtle in opposition to the sun and its primary season.

(Green Sea Turtle, ref. Wikipedia) |

|

"... From the natives of South Island [of New Zealand] White [John] heard a quaint myth which concerns the calendar and its bearing on the sweet potato crop.

Whare-patari, who is credited with introducing the year of twelve months into New Zealand, had a staff with twelve notches on it. He went on a visit to some people called Rua-roa (Long pit) who were famous round about for their extensive knowledge.

They inquired of Whare how many months the year had according to his reckoning. He showed them the staff with its twelve notches, one for each month. They replied: 'We are in error since we have but ten months. Are we wrong in lifting our crop of kumara (sweet potato) in the eighth month?'

Whare-patari answered: 'You are wrong. Leave them until the tenth month. Know you not that there are two odd feathers in a bird's tail? Likewise there are two odd months in the year.'

The grateful tribe of Rua-roa adopted Whare's advice and found the sweet potato crop greatly improved as the result. We are not told what new ideas he acquired from these people of great learning in exchange for his valuable advice. The Maori further accounted for the twelve months by calling attention to the fact that there are twelve feathers in the tail of the huia bird and twelve in the choker or bunch of white feathers which adorns the neck of the parson bird ..." (Makemson) |

|

In the so called 2nd list of places, ordered clockwise around Easter Island (i.e. contrary to the order in which the dream soul (kuhane) of Hau Maka visited localities hônu is mentioned in the 59th place:

| 58 "ata popohanga toou e to ata hero e

'Yours is the morning shadow' refers to an area in Ata Hero where the house of Ricardo Hito is now located. |

| 59 "ata ahiahi toou e honu e

'Yours is the evening shadow' belongs to a 'turtle'. I could not obtain any information about the location, but I suspect that the 'turtle' refers to a motif in the narration of Tuki Hakavari (the turtle is carved in stone in a cave along the bay of Apina).

The contrasting pair 'morning shadow vs. evening shadow' establishes a definite spatial relationship." (Barthel 2) |

The front side (ra'e), which I have suggested to be the temporal opposite (spring, a.m.) of the back side (tu'a) is here expressed as the opposition between 'morning shadow' and 'evening shadow', and the turtle 'owns' the evening shadows (ata ahiahi). Hero means the yellow colour of ripe bananas.

59 is twice 29.5 or the number of nights for a synodic month. In a way 59 therefore marks the end (and new beginning) - exactly the function of the hônu glyph type. Furthermore, Barthel has ordered the 2nd list of places in parallel with the phases of the moon and there ata ahiahi toou e honu e is in parallel with the beginning of the waning moon. We recognize how in the E calendar at the beginning of waning sun (period 12) hônu glyphs appear.

Turtles are located both at the beginning of the 1st 'year' and at the beginning of the 2nd 'year'. At the beginning of the 1st 'year' (winter solstice) a new fire will be alighted and therefore a turtle is needed. At the beginning of the 2nd 'year' a turtle must quench the fire. In the G calendar we see the same structure - only the 1st 'year' here seems to begin around spring equinox and end around autumn equinox, the 'years' are defined by equinoxes and not by solstices.

|

|

It may be coincidence, but probably it was a wordplay from Metoro when he said ero (very much like hero) at the first glyph documenting early dawn in the 'day calendar' according to Tahua:

|

|

| Aa1-16 |

Aa1-17 |

| ka ero |

ka tapamea |

The Polynesian languages are slippery, however, and we must not dismiss hiero = to shine, to appear (of the rays of the sun just before sunrise). He hiero te raá, dawn breaks.

Probably the yellow of ripe bananas (hero) and the rays of the sun immediately before sunrise (hiero) have a lot in common, not obvious for other than Polynesian minds. The common denominator may well be a word ero, now no longer used.

A wordplay with vero ('the black cloth') may also be involved, where vero = 'death' and hero = 'birth'. |

|

In this table Barthel has correlated the 2nd list of places with moon phases. I

have reordered the list according to places (while Barthel has an order according to

the moon nights):

|

1 Apina Iti |

2 Hanga O Ua |

21-23 |

21 Roto Kahi |

22 Papa kahi |

1-3 |

|

3 Hanga Roa |

4 Okahu |

22-24 |

23 Puna Atuki |

24 Ehu |

2-4 |

|

5 Tahai |

6 Ahu Akapu |

23-25 |

25 |

26 |

3-5 |

|

7 Kihikihi Rau Mea |

8 Renga Atini |

24-26 |

27 Hakarava |

28 Hanga Nui |

4-6 |

|

9 Vai A Mei |

10 Rua Angau |

25-27 |

29 Tongariki |

30 Rano Raraku |

5-7 |

|

11 Roro Hau |

12 Vai Poko |

26-28 |

31 Oparingi |

32 Motu Humu Koka |

6-8 |

|

13 Hereke |

14 Hatu Ngoio |

27-29 |

33 Hanga Maihiku |

34 Maunga Toatoa |

7-9 |

|

15 Ara Koreu |

16 Hanga Kuokuo |

28-30 |

35 Pipi Horeko |

36 Hanga Tetenga |

8-10 |

|

17 Opata Roa |

18 Vai Tara Kai Ua |

29-31 |

37 Ahu Tutae |

38 Oroi |

9-11 |

|

19 Hia Uka |

20 Hanga Ohiro |

30-32 |

39 Akahanga |

40 Hua Reva |

10-12 |

|

Uncertainty is the reason for a standard interval of 3 nights for each pair of localitites.

Uncertainty is also the reason for the vacant place names. The names may be shifted one position forward or backward and are therefore not recorded in the table.

59 Ata Ahiahi (the location of the turtle) may by an educated guess be referred to the 21th night, because Haga Hônu is number 21 in the kuhane voyage. |

41 |

42 |

11-13 |

|

43 |

44 |

12-14 |

|

45 |

46 |

13-15 |

|

47 |

48 |

14-16 |

|

49 Hanga Te Pau |

50 Rano Kao |

15-17 |

|

51 Mataveri O Uta |

52 Mataveri O Tai |

16-18 |

|

53 Vai Rapa |

54 Vai Rutu Manu |

17-19 |

|

55 Hivi |

56 Puku Ohu Kahi |

18-20 |

|

57 Hanga Piko |

58 Ata Popohanga |

19-21 |

|

59 Ata Ahiahi |

60 Apina Nui |

20-22 |

|

|

The turtle is a

creature of the water and therefore in opposition to the lightgiving

heavenly bodies, foremost the spring sun (Rigi). Light comes from fires and the

two elements water and fire are in opposition. When Rigi 'dies' it is

the work of the turtle.

The spring sun 'dies' at summer

solstice because from that point onwards he is waning. Sun also

'dies' at autumn equinox because then he emigrates to the

other side of the equator.

The reason why the

turtle is needed also when a new fire is to be alighted is not

difficult to understand: The turtle has 'taken' the fire and he

must now return it. In nature everything takes and gives, there must be

a balance.

Finally, fires have

flames which rise towards the sky while water instead runs

downwards. Heaven (up) belongs to the birds (gods) and the sea

(down) belongs to the sea creatures. We live in the middle. The

Mayan concept of the turtle as a creature of the middle world does

not apply to sea turtles.

|

|

.jpg)