204. We should then turn our attention to side a (the side of war) in order to similarly count also its figures: "The best present form of the artifact is a reconstruction, presenting a best guess of its original appearance. It has been interpreted as a hollow wooden box measuring 8.50 in wide by 19.50 in long, and inlaid with a mosaic of shell, red limestone and lapis lazuli. The box has an irregular shape with end pieces in the shape of truncated triangles, making it wider at the bottom than at the top. Inlaid mosaic panels cover each long side ... The two mosaics have been dubbed 'War' and 'Peace' for their subject matter, respective a representation of a military campaign and scenes from a banquet." (Wikipedia)

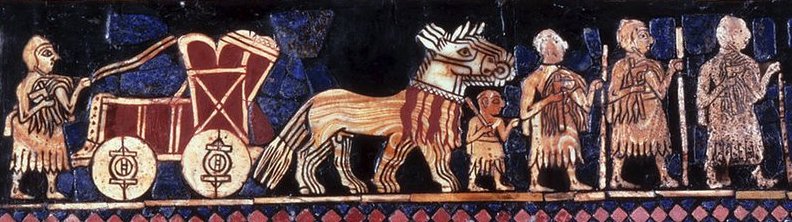

But how should we treat the first part at top left? Is this great war chariot a figure to be counted separately from the person standing at its left? And the chariot is obviously drawn not only by one but by 4 horses. I.e., it is a quadriga. 4 (wheels) * 4 (horses) = 16 = 64 / 4. ... Lifting a huge doorstone, such as two and twenty good four-wheeled wains could not have raised from the ground, he set this against the mouth of the cave, sat down, milked his ewes and goats, and beneath each placed her young, after which he kindled a fire and spied his guests ...

... And possibly a war chariot was symbolized by number 64, because we can in the illustration above count to 32 spokes for each wheel. 5 * 64 = 320 (→ Dramasa, *320, the South Pole star). A chess board carries 32 black and 32 white squares ... However, the golden Roman quadriga above should then be counted as 2 * 5 = 10. Or perhaps as 10 (spokes) + 4 (horses) = 14. Or maybe as 10 + 16 (horse legs) + 4 = 30. ... OgotemmÍli had his own ideas about calculation. The Dogon in fact did use the decimal system, because from the beginning they had counted on their fingers, but the basis of their reckoning had been the number eight and this number recurred in what they called in French la centaine, which for them meant eighty. Eighty was the limit of reckoning, after which a new series began. Nowadays there could be ten such series, so that the European 1,000 corresponded to the Dogon 800. But OgotemmÍli believed that in the beginning men counted by eights - the number of cowries on each hand, that they had used their ten fingers to arrive at eighty, but that the number eight appeared again in order to produce 640 (8 x 10 x 8). 'Six hundred and forty', he said, 'is the end of the reckoning.'

And the little (→ Litr) guy (dwarf) under the 4 horse noses might belong in the first figure too, in which case also his 3 fellows in front ought to belong.

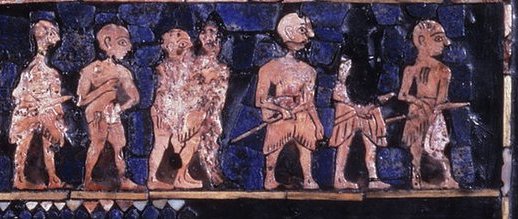

The central panel could be easier to count. Let's begin there. First there are obviously 8 persons to be treated as a group. But then we have to decide how to treat the enemies who are defeated:

I guess we should here count to 7. Also enemies should be regarded as figures to be counted with. Next problem is the final part of the central panel:

I at first decided to count 4 + 3 = 7, which suggests the central panel on side a maybe should not be regarded as belonging to Saturn (as perhaps on side b) but instead possibly to Mercury. 12 * 22 = 264 (= 3 * 88). Although here my imagination intervened and saw Moon, Mars, Mercury (a double character), Jupiter, Venus, and Saturn (leaving Sun aside). 3 + 3 = 6:

21 * 12 (a palindrome) = 36 weeks. The last part of the top panel should then be comparatively easy to count, for it clearly contains 1 + 6 + 5 = 12 figures:

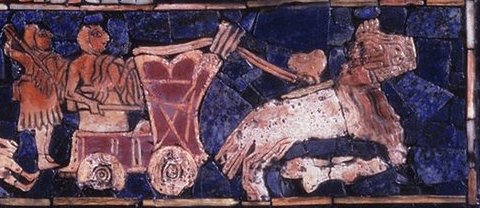

Should we disregard the inanimate chariot at the beginning of the top panel, but count all its 4 horses and also the little one in front, the result of the top panel seems therefore to be 21 figures (→ Mars, a character of war). The bottom panel carries 4 chariots, which we provisionally will not count, but then there are 2 persons on each such chariot which should be recorded. And then there are 1 + 2 + 1 = 4 defeated enemies under the last 3 chariots. 4 * 2 + 1 + 2 + 1 = 12 persons in all: However, we should not forget to count the horses. And perhaps we should count also the chariots, possibly each of them as 64:

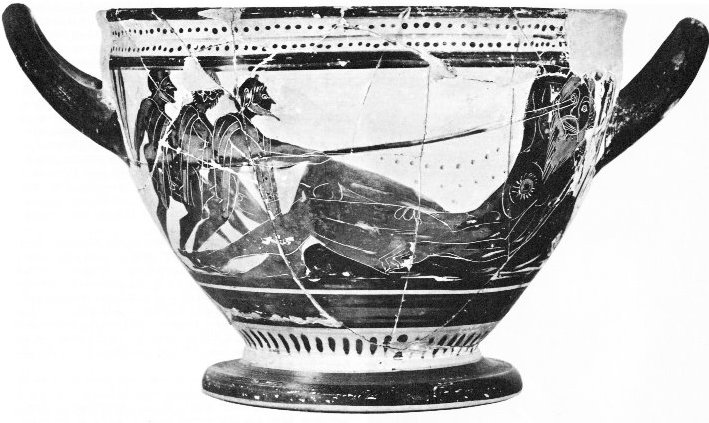

But obviously each of the 4-wheeled war chariots should rather be counted as 4 * 2 = 8, we can see from how their wheels have been designed:

Possibly, though, with exception for the last chariot in the bottom line:

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

.jpg)