|

TRANSLATIONS

Here I have attempted to revise the structure (in my mind) of the night calendar in Tahua. Perhaps there is at midnight an expected meal (which will expand your waist), expressed by the thicker tôa (in 4 above). If so, then this tôa glyph will be better understood if read in conjunction with the following henua (III) marking midnight. The new structure (above) has 8 (i.e. a sign of the moon = night) lines, each starting with a tôa and followed by some kind of 'determinant' sign - either as a separate glyph or as an explicit part of the glyph. Notably Metoro in his readings seems to have regarded such parts of glyphs as equivalent to separate glyphs. These 'determinant' signs are placed after the main (tôa) sign in the night calendar. In the day calendar the reverse is (obviously) clear: the 'determinants arrive before the main (tapa mea) signs. The 'mirrors' at dawn and dusk which accomplish these reversals of order also may effect a reversal of up and down in such glyphs which have been rotated 90o (by way of changing right into left and vice versa). The red numbers (above) denote glyphs which I regard as possibly having to do with light. But that does not mean they therefore necessarily belong to the day. There is light in the night too (arriving from other sky 'people' than the sun). We have 12 glyphs in the night calendar and 8 'periods'. I have divided these 8 'periods' into halves, and marked one half with red and the other with blue (meaning 'light' respectively 'dark'). The 'female' side has both 'light' and 'dark' (whereas the 'male' side pretends to have only 'light'). The 'female' is characterized by 4, therefore 4 'light periods' and 4 'dark periods'. Undeniably, though, there are 10 tôa glyphs in this night calendar. Perhaps significantly the 2 'periods' where I have packed together two such glyphs show 8 marks, as if to secure a correct reading (i.e. 8 periods, not 10). If we count all glyphs (respective parts of glyphs when the glyph is mixed), we arrive at 19. If we then subtract those parts of glyphs which announce 8 we have 16 left (= 2*8). If I have understood the structure, then Aa1-43

represents the time period from midnight until noon. At noon there should then be a sign of the 2nd time period of this kind, stretching from noon until midnight. Two henua we cannot though find at noon, maybe because the time period noted in Aa1-43 is the new day - stretching from one midnight to the next midnight. That would be in harmony with counting years from one midwinter solstice to the next. The sign at noon of sun emerging from the elbow (Aa1-24)

indicates a new time period. Noon corresponds to midsummer solstice and Metoro seems to have said that the sun was arrested (mama'u) - though of course he knew that the glyph stood in the middle of the day and not in the middle of the year. What was arrested may have been not the speed but the further advancement of the sun southwards (upwards). On the other hand, identifying day with year there should indeed be changes in the speed of the sun's daily journey across the sky. At noon and midnight sun ought to move slower - if there was a good correspondence - because at the solstices the movement of the sun appears to reach standstill. But the time of the year also influences the time of the day and according to Needham 3: "What the sundial measures is true or apparent solar time, but owing to the eccentricity of the earth's orbit, which gives the sun its apparent unequal rate of motion ... true solar time and mean solar time do not coincide ..." "The effect is due ... to two circumstances, the eccentricity of the earth's orbit, and the difference between the planes of the equator and the ecliptic; the greatest positive difference between clock-time and sundial time (14½ min.) occuring in February, and the greatest negative difference (16½ min.) in November. This is know as the Equation of Time." "Of the two components of this difference between dial time and clock time, the eccentricity factor vanishes only at perigee and apogee, but the obliquity factor vanishes at both equinoxes and both solstices." In February clock-time tells us that sun is lazy, being a quarter of an hour late, in November the opposite rules. "... the Chou and Han system of equal or equinoctial double-hours was extraordinary modern. In Europe it was not until the coming of mechanical clocks in the +14th century that the old system of varying the length of the hours according to the length of the day was abandoned. But in China by the -4th century at latest a permanent system of 12 equal double-hours, starting at 11 p.m., divided each day and night. By a curious contrast, variable or temporal hours continued in Japan as late as +1873, and the pointer-readings of mechanical clocks were cleverly adapted to them." We should note here, that the Chinese first double-hour started before midnight and ended after midnight. This might mean that in this period:

tôa is located before midnight and henua after midnight. Maybe, also, the curious 1st period of the night in some curious way straddles dusk, due to fear of the 'leap' between day and night, the fear of disorder and the unknown. Double-hours during the day correspond to double-months during the year, and the 'leap' at the time of new year / new king is patched over by the double-month Maro-Anakena (as I suspect): "... each new king went to live at Ahu-a-kapu, near Tahai on the west coast. Later when he had yielded his authority to his son, he went to ahu Tahai and then to Anakena where he spent his last years..." "The list of names of localities is divided into two subseries of unequal length. While the first twelve pairs (reading horizontally) are topographic stations along the dream soul's path in search of the future residence of the king, the last two pairs represent places of political importance (25 and 26 are the residences at Anakena of the current king; 27 and 28 are the residences of the future king and of the abdicated king)." Each double-month consists of 4 half-months and each half-month is a station on the journey of the kuhane of Hau Maka. Stations 25-28 correspond to one double-month, presumably Maro-Anakena. A similar structure for dusk would mean that the first two tôa of the night calendar correspond to Anakena (which comes after Maro in the calendar for the year). But instead (clearly) Maro is written in the night calendar. Passing dusk a kind of reversal seems to occur. However, Anakena means the 'residences' of the current king (stations 25-26), and therefore Maro could point to the 'residences' of the future king (station 27) and the abdicated king (station 28). These two stations (27-28) may be alluded to in

Investigating once again the last periods of the day calendar we may now suspect an allusion to Anakena:

The two heads together in the last period of the day may represent the old and new kings, and the death signs in the 9th period could be interpreted as the time of abdication. We may see the middle apex flame of the sun as a symbol for the sharp change at a mountain peak, the toga glyph as a sign of 'death' ('winter', 'post supporting the roof', 'sudden movement', 'eat enough') and the reversed tapa mea as not only a sign of reversal but also as an allusion to the five extracalendrical days at new year. Anakena was the landing site of Hotu Matu'a, which may be interpreted as the place of the beginning of his rule. "If the sunset [at winter solstice] was viewed from Poike it would have taken place in the direction of Anakena, the name of the first month of their calendar, the landing place of Hotu Matu'a, the birth place of the island culture and the traditional home of the ariki mau." (van Tilburg) So although Maro arrives before Anakena in the yearly calendar, in the calendar of the 'day' the reverse may signal the more true circumstances - that there is an abdication and transfer of rule first (Anakena) and later the end (Maro). Kena = A sea bird, with a white breast and black wings, considered a symbol of good luck and noble attitudes. Moa tu'a ivi raá, 'sun-back chicken': chicken with a yellow back which shines in the sun. White breast (in front) could mean the coming light and yellow back the light behind. The shape of henua in Aa1-43

with the short ends impressed (concave or apex-formed) may mean that the solar time - as defined by the sun-dials - varies, that the days are unequal in length. If on the other hand henua has straight short ends

that could mean the water time, the steady time according to the clepsydras. "It is ... quite certain that the clepsydra was not invented in China. Both in Babylonia and in Egypt, as we know from cuneiform texts and from actual objects and models recovered from Egyptian tombs, it had already been used for centuries by the time of the early Shang period (c. -1500)." (Needham 3) The oppostion between sun and water emerges here as a natural consequence of the two different ways to measure time. We now understand why the times of light and life (due to the rays of the sun) were opposite to the times of night and death (due to the cold water); the dynamic ('male') yang balancing the static ('female') yin. Needham (3) dismisses the study of calendars as not scientific: "A calendar is only a method of combining days into periods suitable for civil life and religious or cultural observances. Some of its elements are based on those astronomical cycles which have obvious importance for man, such as the day, the month and the year; others are artificial, such as the week and the subdivisions of the day. The complexity of calendars is due simply to the incommensurability of the fundamental periods on which they are based. 'The supply of light by the two great luminaries', writes Fotheringham (1), in one of the best general accounts of the subject, 'is governed by the periods known to astronomers as the solar year and the synodic month, while the return of the seasons depends on the tropical year. The length of the synodic month at the present time is 29.5305879 days, while that of the tropical year is 365.24219 days.' Calendars based on the former figure, depending only on lunations, make the seasons unpredictable, while calendars based on the later cannot predict full moons, the importance of which in ages before the introduction of artificial illuminants was considerable. The whole history of calendar-making, therefore, is that of successive attempts to reconcile the irreconcilable, and the numberless systems of intercalated months (jun jüeh), and the like, are thus of minor scientific interest." I think Needham has misunderstood the foundations of science, where harmony and beauty always have been participants in deciding what basic models to chose in describing nature. Science cannot be just the overstructures built on the fundamental models, it must also study its own roots. "The presence of the radical for 'king' in this character [jun jüeh] well indicates the arbitrary social element in calendar-making.

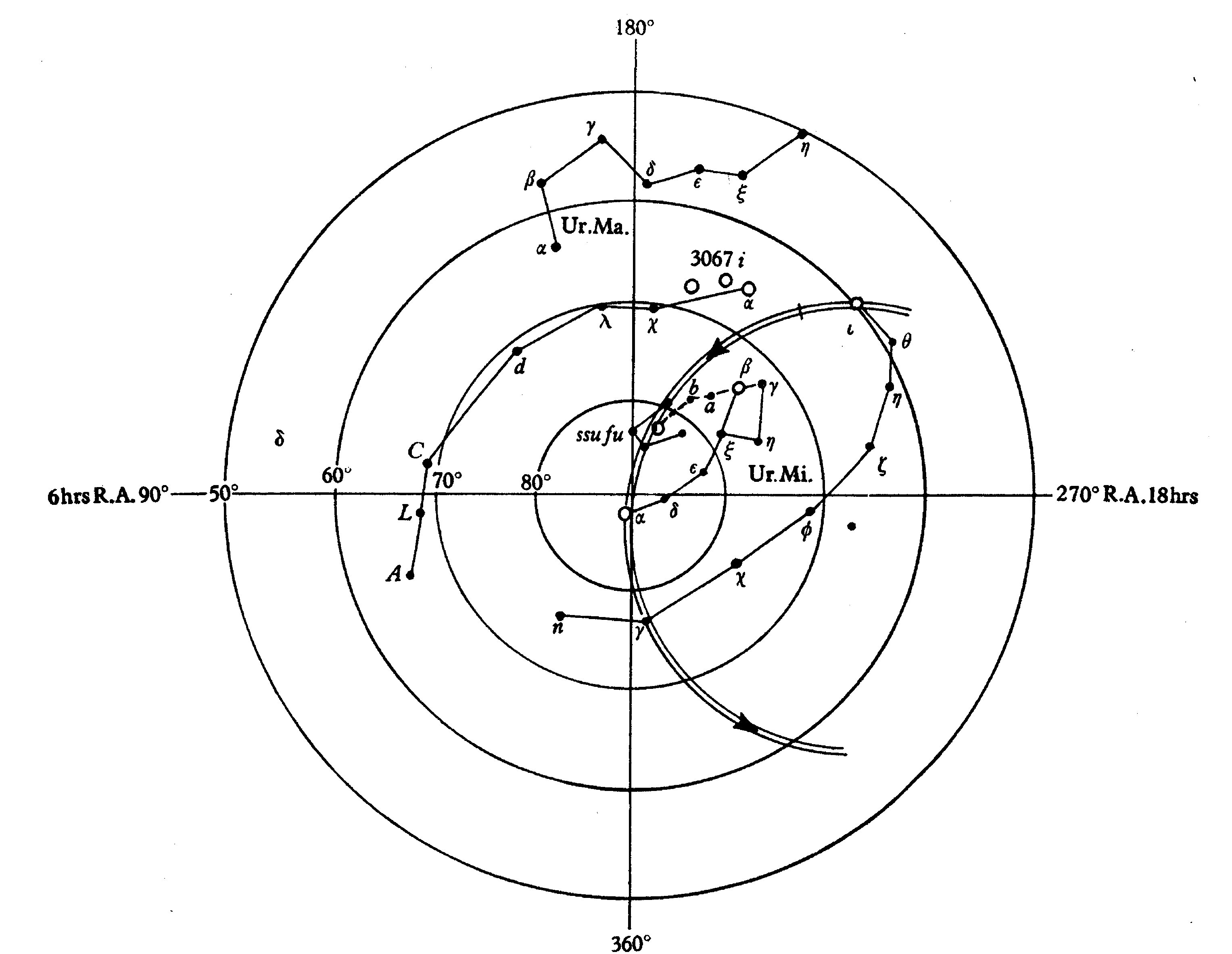

It is indeed 'the king standing in a gateway' and Soothill (5), p. 62, makes the suggestion that it refers to the emperor's station on the threshold between one room of the Ming Thang [Bright Palace, 'the mystical temple-dwelling which the emperor was supposed to frequent, carrying out the rites appropriate to the seasons'] and another when an intercalary month intervened in the normal cycle of his perambulation." The study of human ideas certainly may be a scientific one. The methods of such a study must, however, be fundamentally different from those of ordinary mainstream science, it must e.g. search for many covariant causes: Maybe the picture in the henua type of glyph is a wooden log or stick. The use of such a picture as a symbol for 'time period' - if that is a correct interpretation - certainly is not evident without considering all possibly relevant information. I have suggested that the stick was imagined to be a gnomon, and that the gnomon stick drawn as henua would then be interpreted as a period of time-space. We have now heard about the king standing in the doorway to a new time-space period (room). He must be standing on a (wooden) threshold, another possible origin for the picture in henua. If that is the picture imagined in henua, this picture would equally well be suitable as a symbol for a period (or its beginning/end). We could then continue by considering the possibility that the picture in henua is representing a piece of bamboo (or other similar hollow stick): "Before Han times it was believed that the pole star was in the centre of the sky, so it was called Chi hsing ('Summit star'). Tsu Kêng (-Chih) found out with the help of the sighting-tube that the point in the sky which really does not move was little more that 1o away from the summit-star. In the Hsi-Ning reign-period (+1068 to +1077) I accepted the order of the emperor to take charge of the Bureau of the Calendar. I then tried to find the true pole by means of the tube. On the very first night I noticed that the star which could be seen through the tube moved after a while outside the field of view. I realised, therefore, that the tube was too small, so I increased the size of the tube by stages. After three months' trials I adjusted it so that the star would go round and round within the field of view without disappearing. In this way I found that the pole-star was distant from the true pole somewhat more than 3o. We used to make diagrams of the field, plotting the positions of the star from the time when it entered the field of view, observing after nightfall, at midnight, and early in the morning before dawn. Two hundred of such diagrams showed that the 'pole-star' was really a circumpolar star. And this I stated in my detailed report to the emperor." (Shen Kua according to Needham 3)

All three alternatives (gnomon, threshold, sighting-tube) are - as I judge it for the moment - equally possible explanations for the picture in the henua type of glyph. And if I can see all three at once like this, then certainly also the inventors of the rongorongo glyphs could see them. In fact, I believe that if there had been just one alternative, then they would not have used its picture as the basis for a glyph type. Therefore we should not try to eliminate 'false' explanations (as in normal science). Instead we should search among the surrounding associations for such 'suitable for civil life and religious or cultural observances'. All three alternatives have connections with the 'king' and that makes them 'heavy' (cfr 'heave'): They all have to do with time/space and that is the king's business. The uses of a gnomon, a threshold, a sighting-tube - i.e. their symbolic value - are primarily focused on where the 'rule' must change. The 'rule' is the king. We may translate it as his 'habits'. If we do that, then it becomes understandable why Metoro used the word henua. Certainly the word means 'earth', but I guess that Metoro thought about 'habitation'. The 'habits', or 'rules', also incorporates what we wear and what we do, in other words: the habitation. If the king is changed, then all the rest will also go away. The new king will institute new 'habits'. The non-moving 'summit' around which everything revolves is a good symbol for the 'king'. Remember, too, that a gnomon may be used also during the night while searching for this immovable rock: "I became curious about this star ... called Nuutuittuq [= 'never moves'] ... So, on the lee side of our uquutaq {a snow windbreak} I positioned a harpoon pointing directly at this particular star to see if it would move. In the morning I checked it and discovered that the Tukturjuit {Ursa Major} had changed their position completely but the harpoon still pointed at this star.... I had discovered the stationary star ... " (Abraham Ulayuruluk of Igloolik according to Arctic Sky.)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||