|

TRANSLATIONS

I regard it as certain (an axiom) that these 12 glyphs describe the dark time of the 24 hours of a 'day'. From this the translation will proceed. I have chosen to begin this new phase in the translation with the text of Tahua (A) because its day calendar differs in two fundamental respects from the texts in the other three tablets: 1. The design of tapa mea is different. 2. The daytime description arrives before the description of nighttime . 1. Searching through all the glyphs in Tahua I can find no occurence of a tapa mea type of glyph which is designed with the shape of a moon sickle, all are lenticular. 2. The fact that daytime arrives before nighttime, according to the author of A, is presumably evident also in the design of the tapa mea type of glyph, e.g. in (Aa1-25):

In the rotated glyph (right) east is located where the elliptical line is broken through, reasonably a way to show where a new 'day' (24-hour period) begins. Another interpretation would be that it is the time when the period of light begins, but that would not harmonize with my view of the bottom (non-marked) part of the oval shape representing the dark period of the 'day'. Why is the text of Tahua different? Possibly it was created at another time than the other three tablets, at a time when the model of cosmos had changed. A model which shows the path of the sun as elliptical is more modern than a model similar to that in old Babylonia (where there is no sky for the sun to move across on the other side). "The fact that 'Tahua' is a European or American oar comprises the best physical evidence for the recent elaboration of Easter Island's rongorongo script. Its excellent condition bespeaks a very recent manufacture, dating to perhaps shortly before the end of rongorongo in the 1860s." (Fischer) Possibly Tahua is one of the very last rongorongo text produced. I have not yet any means to quickly ascertain which more texts never use the old (?) tapa mea type with sickle-shape, but I can see that at least Keiti (E) is similar to Tahua in this respect. Maybe impressions from the time of Eyraud made the inhabitants on Easter Island change their views not only about how the sun moved during the night, but also as to the proper way to think about when a day should begin? "Rapanui's rongorongo inscriptions were to be first described to the outside world at their very demise, the honour of penning their obituary falling to the Frenchman Joseph-Eugène Eyraud (1820-68), Easter Island's first known non-Rapanui resident ... From his Bolivian mining interests Eyraud had become moderately well-to-do and, emulating his missionary brother Father Jean Eyraud of China in wishing to dedicate his fortune and talents to the Congrégation des Sacrés-Coeurs ... he eventually sailed on his own recognisance ... to Rapanui where from January till October of 1864 he tested the feasability of an authorised Catholic mission to the island." (Fischer) The type of glyph which during nighttime presumably corresponds to the daytime tapa mea is what I will call tôa (sugar cane):

It will be noted that Tahua has 10 glyphs of this kind during the nighttime (see above), i.e. the same number as (according to Tahua) the number of tapa mea during daytime. The total number of glyphs during daytime is (in the Tahua text) 21, during nighttime 12, which sums up to 33 glyphs, a seemingly very strange number considering how they avoided odd numbers and strived to reach for not only even numbers but also meaningful numbers. But this calendar starts with 3 glyphs:

already before the daytime description (as I have presented it), and presumably we should therefore include these 3 in the number of daytime glyphs. We then reach 3 + 21 = 24, which indeed is both an even number and a very meaningful one. Also we reach 24 + 12 = 36 (= 360 / 10) for the total calendar. We should furthermore note that the distribution of the tôa glyphs is arranged to avoid splitting them in the middle, thereby reaching an odd number (5). Instead we have them arranged in 6 glyphs before midnight and 4 after midnight (midnight being defined by a henua glyph). All four texts (A, H, P and Q) agree on a henua type of glyph being necessary in the middle of the nighttime. Presumably this is because the beginning of the year was defined to the darkest time of the year. "The most ancient of all astronomical instruments, at least in China, was the simple vertical pole. With this one could measure the length of the sun's shadow by day to determine the solstices ... and the transits of stars by night to observe the revolution of the sidereal year. It was called pei or piao, the meaning of the former being essentially a post or pillar, and the latter an indicator. Pei can be written with the bone radical ... or with the wood radical, in which case it means a shaft or handle. Ancient oracle-bone forms of the phonetic component show a hand holding what seems to be a pole with the sun behind it at the top ...

so that although this component alone came to mean 'low' in general, it may perhaps have referred originally to the gnomon itself. This is after all an object low on the ground in comparison with the sun, and shows the long shadow of a low sun at the winter solstice, the moment which the Chinese always took as the beginning of the tropic year." (Needham 3)

This picture (from Needham 3) shows how even today in Borneo they measure the shadow of the sun with a gnomon and a gnomon template to determine summer solstice. Notice the little figure on top of the gnomon, maybe a representation of the sun. (With protruding belly?) What does the tôa type of glyph show us a picture of? Judging from the lengthy and difficult discussions about tapa mea we should not expect any easy and simple answers. Instead we should expect several more or less true answers, not excluding each other. I will here try to point at some of the possible answers about tôa: 1. Of old people thought that the moon when in its dark invisible phase was in a box, a sack or some similar container, thereby explaining its total disappearance. (Ref. Zehren). The tôa glyph type may show some sort of container, perhaps a container for keeping drinking water in? Two openings at the top would be useful, you drink from one of them and the other lets air in so the drinking will be easier. As the dark world is located downwards, water should be there. 2. In the Mamari moon calendar we can see that during the waxing phase of the moon there is a fish with head upwards for every period, while for every period of waning moon there is a fish with head downwards, e.g. (Ca6-21 and Ca7-29):

One of the probable meanings of the sign fish is to indicate life (by way of the life's characteristic, viz. movement). We have (probably) seen this quick fish sign in combination with sun in e.g. Pa5-43:

By inverting the fish so that its tail points upwards the meaning will also be inverted: a sign of death. That explains why in the waning moon periods (of Mamari) the fishes have been inverted; the black area is increasing. In my glyph dictionary I have three glyph types relevant to this discussion:

The first one is an inverted fish, the second one is a 'fish', while the third is tôa. There is a general similarity in shape with 'feet' up (meaning, presumably, non-life). The 'fish' (îka) depicts a hanging body, though not of a fish but of a sacrificed person:

Given this information, we may then go back one step and question whether really the inverted G38 is an (ordinary) fish. According to Churchill 2 there are fishes and Fishes: "... 'I'a is the general name for fishes', Pratt notes in his Samoan dictionary, 'except the bonito and shellfish (mollusca and crustacea).' We may forgive the inaccuracy of the biology in our gratitude for the former note. The bonito is not a fish, the bonito is a gentleman, and not for worlds would Samoa offend against his state. The Samoan in his 'upu fa'aaloalo has his own Basakrama, the language of courtesy to be used to them of high degree, to chiefs and bonitos. One does not say that he goes to the towns which are favorably situated for the bonito fishery; he says rather that (funa'i) he goes into seclusion, he withdraws himself. He finds that the fleet which is to chase the bonito has an honorable name for this use, that the chief fisher has a name that he never uses ashore. He will not in so many words say that he is going to fish for bonito, he says that he is going out paddling in the courtesy language (alo); he even avoids all chance of offending this gentleman of his seas by saying, instead of the blunt vulgarity of the word fishing, rather that he is headed in some other direction (fa'asanga'ese). He does not paddle with the common word but with that (pale) which he uses in compliment to his chief's canoe. He will not so much as speak the word which means canoe; he calls it by another word (tafānga), which may mean the turning away to one side. In this unmentioned canoe he may not carry water by its common name, he must call it (mālū) the cool stuff. He will not mention his eyes in the canoe; he calls his visor (taulauifi) the shield for his chestnut leaves. Even the word large becomes something else (sumalie) in this great game. The hook must be tied with ritual care; it is called (pa) out of the common name for hook, no bonito will take a hook which has not been properly tied; the fastening is veiled under the name (fanua) for the land. There are many rules to observe; their disregard is called (sopoliu) the stepping over the bilges, from the most unfortunate thing that the fisher can do. He may hail the bonito by his name (atu), or he may call him affectionately or coaxingly (pa'umasunu) old singed-skin. If he has the fortune to hook his bonito he must raise the shout of triumph, Tu! Tu! Tu e!, not his whole name but one of it syllables; he triumphs as over a foe honorably slain in combat, but he avoids hurting the feelings of the other gentleman of the sea. The first bonito caught in a new canoe he calls (ola) life; the first bonito caught in any season bears a special name (ngatongiā), of uncertain signification, and he presents it to his chief. His catch he reckons by a special notation; to his numerals he adds the word (tino) body; he counts them as one-body, two-body, three-body. Parts of the gentleman have specific names of their own; his fins (asa) and his entrails (fe'afe'a) are called in terms nowhere else employed; the tidbit of the belly part, which the fisher must give to his chief, is called (ma'alo) by the honorific title of the chief's abdomen. And if the rites were not duly observed, if the hook was not rightly tied, if the fisher was so incautious as to mention his eyes, if one of a hundred faults was committed and the fishing was in vain, then the fisher acknowledges his ill success abjectly by saying that (maloā) he was conquered. Such is the language Samoans use to the gentleman of the seas, and he is not i'a."

Australian bonito, Sarda australis (picture from internet) The equivalents in the H/P/Q texts to the tôa type of glyphs in A are sometimes glyphs belonging to the type rau hei ('mimosa branch', a euphemism for hanged victim):

Metoro often used the word 'toa' at GD47:

I can see no resemblance between sugar cane plants (in bloom or not) and the glyph type GD47. Therefore I guess that Metoro indeed meant to'a and not tôa. But I will keep the label tôa for GD47 (as a reminder). If a murderer kills somebody to hang him as a sacrifice to the gods from a branch in a tree, won't he sooner or later be hanged himself? No action without a reaction. Is that why Metoro said to'a when he saw a hanging 'fish' or did he really see a to'a? Perhaps he saw the murderer in his victim, saw to'a by the result of his actions? A hanging fish may therefore signify warrior. The similarity between hanging men and hanging fishes seems real enough: "... They strung them through the heads with sennit, and act called tu'i-aha, and then suspended them upon the boughs of the trees of the seaside and inwards, the fish diversifying the ghastly spectacle of the human bodies, a decoration called ra'a nu'u a 'Oro-mata-'oa (sacredness of the host of Warrior-of-long-face) ..." (Henry) I am not quite sure how high a percentage of the human body is water, but I remember that there is very much water in the bag of human skin, there is no difference between human beings and fishes in that respect. The old Babylonians thought that going south you sooner or later would come to land's end. The other side of the earth was a watery side. The sun could not go down there or he would no longer burn. Therefore chiefs too had to avoid going down, they are also fiery. Which explains their fear of beeing cooked. Chiefs must be kept dry after death. To hang them in trees would not be too bad. Better 'still' of course to be mummified by one's family:

Were there other ways for sun and chiefs to avoid beeing extinguished in the waters below? Was the bonito some kind of submarine survival vehicle? There must have been a time when insight had revealed the world below to be just something quite similar to our own world, while the still waters below continued to haunt men's brains. Or was there water all over the underside of the earth? Even Captain Cook had his orders: to find out if there was any Terra Australis Incognita. I guess the Polynesians also tried to find that land which would ensure a non-watery habitat for the departed ones: "... 'Look over there', said Makea, pointing to the ice-cold mountains beneath the flaming clouds of sunset. 'What you see there is Hine nui, flashing where the sky meets the earth. Her body is like a woman's, but the pupils of her eyes are greenstone and her hair is kelp. Her mouth is that of a barracuda, and in the place where men enter her she has sharp teeth of obsidian and greenstone ... ... And now, they learned, it was Maui's idea to enter her very body. He proposed to pass through the womb of Great Hine the Night, and come out by her mouth. If he succeeded, death would no longer have the last word with regard to man; or so his mother had told him long ago. This, then, was to be the greatest of all his exploits. Maui, who once had travelled eastward to the very edge of the pit where the sun rose, and southward over the great Ocean of Kiwa to where he fished up land, and all the way to the dwelling-place of Mahuika - Maui now proposed a journey to defy great Hine in the west. Taking his enchanted weapon, the sacred jawbone of Muri ranga whenua, he twisted its strings around his waist. Then he went into the house and threw off his clothes, and the skin on his hips and thighs was as handsome as the skin of a mackerel, with the tattoed scrolls that had been carved there with the chisel of Uetonga. And off they went, with the birds twittering in their excitement ..." (Maori Myths) Hine Nui te Po had a mouth like a barracuda - a fish sign. I also remember, though I cannot find it now, that Polynesians seem to have travelled so far south as to have seen the moving greenish curtain patterns in the sky which in the north would have been called aurora borealis. The Polynesian explorers named it 'The Mackerel Sky'. Maui is probably a sun hero. The 'skin on his hips and thighs was as handsome as the skin of a mackerel'. And the skin had also been imprinted with signs of darkness in the form of tattoed scrolls. The ancient Egyptians had the name 'Thigh' for Ursa Major, a constellation in the northern dark area where the stars circle around the pole never 'dying' (never going down at the western horizon). North, for the Egyptians, meant the underworld, the Upper Egypt was represented by a high white 'crown' for the pharaoh, while the headgear for Lower Egypt was red and flat. Going down from Upper Egypt to Lower Egypt you after that will reach land's end, where water begins. Going north meant going down. The northern circumpolar stars couldn't go down because they were already as far down as was possible. On Easter Island going down meant going west. Where, then, was their kingdom of the dead? "... When he had now returned home, and evening fell, the Moon and the woman went to bed, but they had difficulty in sleeping. All along she could hear something groaning. Then the Moon took it and threw it away from the platform - it was the thigh-bone of a seal. His little wife - she was very jealous indeed. He only threw her away ..." (Arctic Sky) The seal lives in the water and a thigh-bone too belongs to the lower half. The Egyptians 'Thigh' is a quite natural choice of name for the major constellation near the bottom. Only one leg there is, around which everything revolves. "... Sometimes, it is told, when the Moon was out hunting and stayed away long, the Sun used to come and peep in. It wore men's kamiks, and its hams were bleeding violently. One day it said to her: 'I have wounds on the hind parts of my thighs, because thy children make string figures, while the Sun shines, at the time of the year when it rises higher in the sky! ..." (Arctic Sky) The lower half of sun's body has hips, thighs, legs and feet and they are in the dark zone. Going up and being north of the polar circle, she will soon reach a point at which no part of her will be below the horizon and of course it then hurts if somebody casts magic spells to whip her, leaving black marks like tattoos. Which brings us to the similarity between feet and roots, both being signs of beginning. Creation is not seen, it is in the dark. "... Ta'aroa, the Creator, was self-begotten, for he had no father and no mother. He sat in a shell named Rumia, shaped like an egg for countless ages in endless space in which there was no sky, land, sea, moon, nor stars. This was the period of continous, countless darkness (po tinitini) and thick impenetrable darkness (po ta'ota'o) ..." (Buck) The black god, Ta'aroa Uri, should live in the water. The month Tangaroa Uri is October, a spring month (10+6-12 = 4 = April), and the 5th station of the kuhane (of Hau Maka) she called Te Kioe Uri (at winter solstice in the month Maro = June). Number 5 signifies darkness by association with those disorderly 5 extra nights between one year and the next, while the following station number 6 then should point at the new order, presumably the new year starting after the winter solstice in June. The upwards journey towards east of the kuhane starts in the dark watery region, where (perhaps) the egg of the new year is waiting (for October?) to be hatched. "Tangaroa came to Easter Island in the form of a seal with a human face and voice. The seal was killed but, though baked for the necessary time in an earth oven, the seal refused to cook. Hence the people inferred that Tangaroa must have been a chief of power ..." (Buck) I think this will do as an introduction to the 2nd possible explanation of what the tôa glyph type may mean. 3. Another explanation might be arrived at by contrasting tapa mea and tôa. If we compare these glyph types with each other we may infer that tôa is what remains of tapa mea after having removed the marks of 'fiery feathers' and added the Y-sign on top:

Though we should first rotate the glyphs to be able to compare them better:

My intuition told me to rotate Aa1-25 counterclockwise but Aa1-40 clockwise. I could also motivate that by the similarity resulting - one little open gap at right (east) in Aa1-25 and two small open gaps at right (east) in Aa1-40, or I could say that the light period (Aa1-25) should follow the path of the sun (from right to left, as seen from a location south of the equator) and that the dark period (Aa1-40) should follow the path of the moon (from left to right, as seen from a location south of the equator). Aa1-40 suddenly took on the shape of a fish. But both glyphs have a boatlike appearance, cfr the left part which looks like the bow of a boat. I think that is as it should be, i.e. I have rotated Aa1-40 in the right manner. If tapa mea is an image of the 'cap' of the sky, then reasonably tôa is an image of the 'cup' of the sky. South of the equator the 'cap' could be the circumpolar area around the south pole of the sky, and the 'cup' its opposite, i.e. the (invisible) area in the north. But the Polynesians inhabit the equatorial band and then the 'cap' may be in the east. Because in the west sun goes down and in the west the ancestors dwell. Maybe, therefore, we should understand the tapa mea view as the eastern side of the sky, and tôa as the western? "Seated at the paddles were the navigators and warrior chiefs in gay girdles and capes of tapa and helmets of various shapes ..." (Henry) Headgears are important signs for chiefs.

The picture is from Captain Cooks 3rd voyage and according to the text (of Beaglehole) the helmets of the warriors are made from calebasses.

Let us now proceed by examining the m.a. (midnight - ante) glyphs:

The first two glyphs seem at first sight to be identical. However, that is not so. A closer look reveals that Aa1-37 is thicker than Aa1-38. We have learnt that such small differences are not random but the results of determined minds. Whatever this sign means, we should notice that it is the same pattern as in the two 'branches' of Y at the top - first a 'fat' one and then a 'lean' one. If - as the author of Tahua suggests - 'day' arrives before 'night', then we may draw the conclusion that 'fat' means period of light and 'lean' period of darkness. During late winter food supplies may be diminishing. During early night food might be served, but hardly late at night. A 'fat' tôa may therefore mean the first half of the night (m.a.) and a 'lean' tôa m.p. We recall the twin sun glyphs during p.m. (with Y-signs at top), where the first one has the order 'fat' / 'lean' whereas the 2nd one has the order 'lean' / 'fat'. Maybe these 4 'branches' (in the form of 2 Y:s) stand for a.m. / p.m. respectively m.a. / m.p.? No that does not fit. Instead the probable pattern still is a.m. / p.m. respectively p.m. / a.m., with Aa1-28 (see below) as a point of balance (noon). The twin glyphs above (Aa1-37--38) resemble signs we have seen earlier in conjunction with 'change of rule', presumably meaning 'double rule', and expressed as glyphs or parts of glyphs showing 'double' or 'split' in some way:

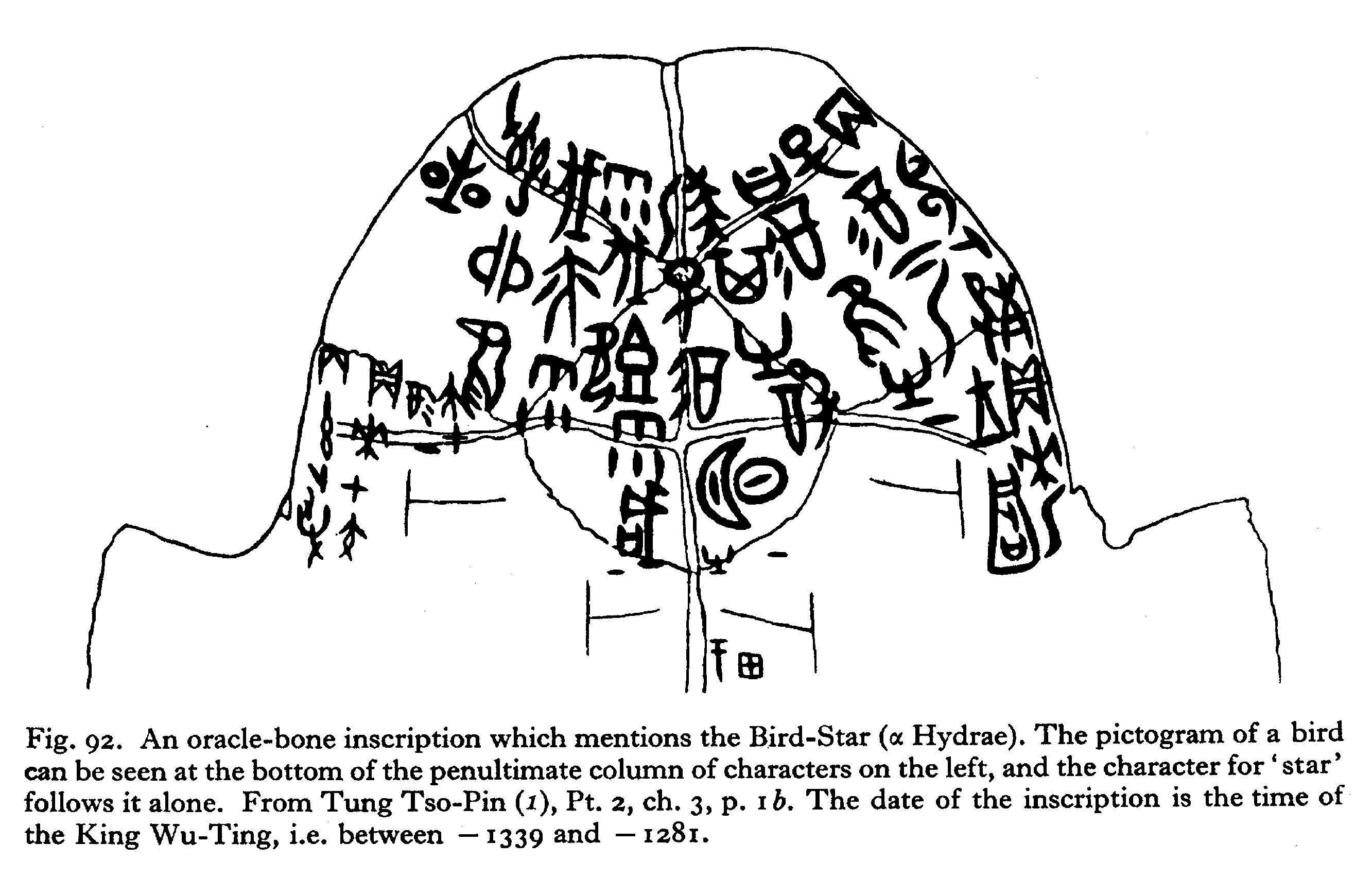

Possibly we should concentrate our attention not so much on the 'branches' (or whatever) which mark 'double' but on the vacancy (vacuum, space, hole) in between: "The shadow definer is made of a leaf of copper 2" wide and 4" long, in the middle of which is pierced a pin-hole. It has a square supporting framework, and is mounted on a pivot ... so that it can be turned at any angle, such as high to the north and low to the south (i.e. at right angles to the incident shadow-edge). The instrument is moved back and forth until it reaches the middle of the (shadow of the) cross-bar, which is not too well-defined, and when the pin-hole is first seen to meet the light, one receives an image no bigger than a rice-grain in which the cross-beam can be noted indistinctly in the middle. On the old methods, using the simple summit of the gnomon, what was projected was the upper edge of the solar disc. But with this method one can obtain, by means of the cross-bar, the rays from the center of the disc without any error ..." (Needham 3) This is interesting. Copper is the metal of Venus. Moreover: "... at the top the gnomon divides into two dragons which sustain a cross-bar ... " Dragons live in the sea: "This was the time [a much earlier time than referred to above in the text about the Shadow Definer] of the ruler Wu-Ting (-1339 to -1281), and on inscribed bones of his reign (as, indeed, on others earlier and later) there are mentions of stars. Of greatest importance were Niao hsing, the Bird Star or Constellation, to be identified with Chu chhiao (the Red bird), i.e. the 25th hsiu, Hsing (α Hydrae), central to the southern palace (the Vermilion Bird) - and the Huo hsing, the Fire Star or Constellation, to be identified with Antares (α Scorpii) and with the 4th and 5th hsiu, Fang and Hsin, central to the eastern palace. Chu Kho-Chen plausibly infers from these names that the scheme of dividing the heavens along the equatorial circle into four main palaces (the Blue Dragon - Tshang lung - in the east, the Vermilion Bird - Chu niao - in the south, the White Tiger - Pai hu - in the west, and the Black Tortoise - Hsüan wu - in the north) was growing up already at this time. The arrangement is clearly seen in Fig. 91.

Besides these two star-names already mentioned, the bones refer also to an important star presumably pronounced Shang, which has not yet been identified,f and to another, the 'Great Star', Ta hsing. f It may, however, be very significant that the Shuo Wên gives Shang hsing as another name for Hsin (no. 5 Antares ... The Tso Chuan also has a legend ... concerning the equinoctial hsiu Shen and Hsin ... in which the word shang occurs. Possibly these would complete the four cardinal-point hsiu.

Fig. 92 shows one of the oracle-bones which mentions the Bird-Star." (Needham 3) Suddenly we have jumped right into a new world of stars and moon stations (hsiu). Indeed there is quite too much information to swallow all at once. We are in the dark but that is necessary. We need to adjust the sensitivity of our eyes. Let us retrace our steps to that gnomon with two dragons and a space in between, where there was a horizontal beam with a tiny hole in the middle, the Shadow Definer. That may be exactly what we need to translate ourselves from the kingdom of the sun ('day') to the queendom of the moon ('night'). In today's morning paper I read about the first time the Swedish people reacted with fury and grabbed their telephones to call and protest to the radio station (at that time - 1938 - radio transmaission was a monopole of the Swedish state). What had happened? For the first time ever the news were read by a woman! Women should not be involved with such horrors as wars and accidents, that is for men. A woman reading the news on the radio disturbed them so much that they couldn't listen to her. You should not mix shadows (water) with sunlight (fire). Instead shadows should measure the sun:

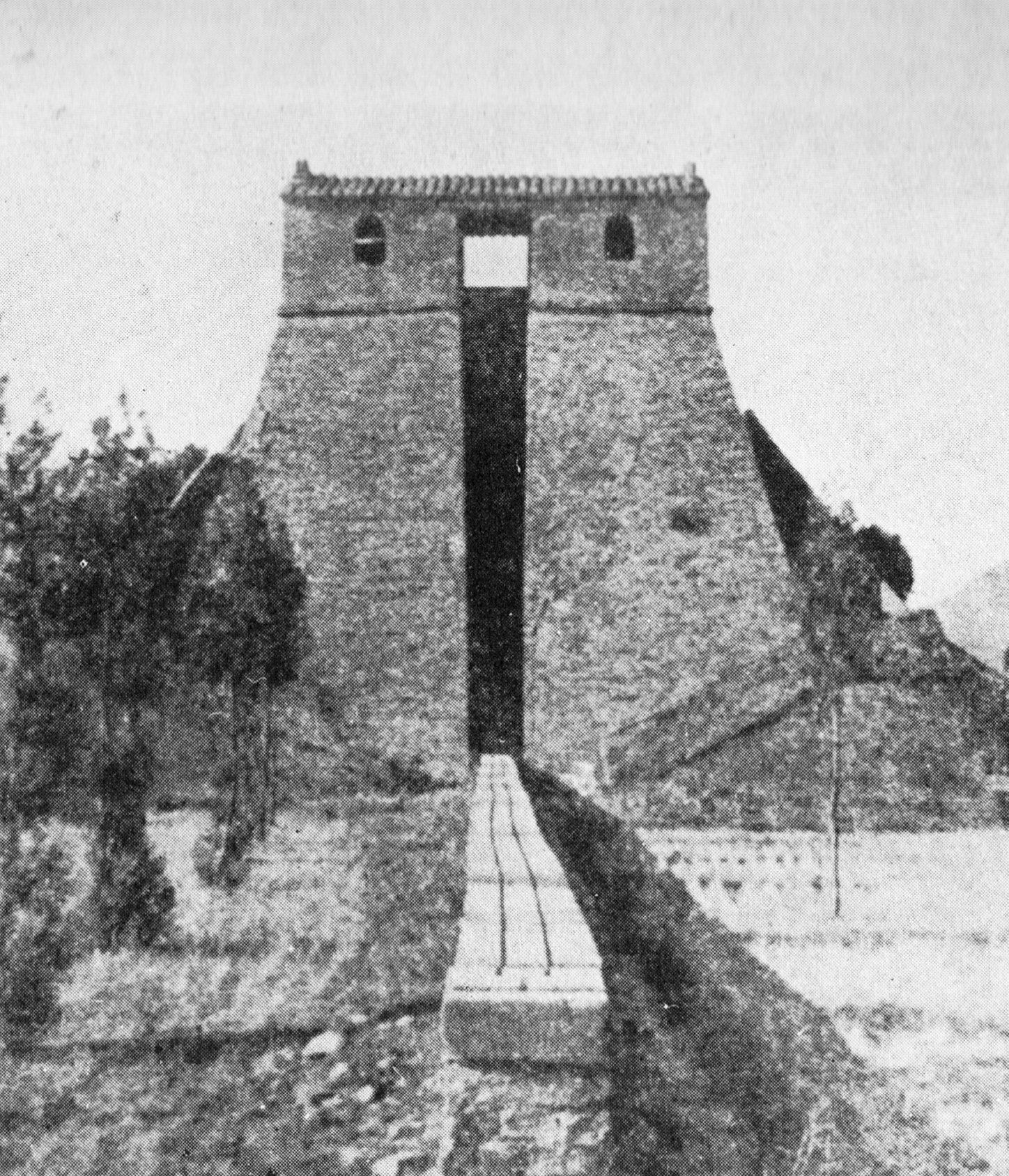

This truncated pyramid (picture from Needham 3) is the Chou Kung Tower at Yang-chhên: "... fitfty miles south-east of Loyang, there still stands a remarkable structure, known as Chou Kung's Tower for the measurement of the Sun's Shadow ... Two stairways lead from ground-level to the platform, upon which there stands, on the north side, a one-storey building of three rooms, the centre one having a wide opening to the north giving a good view of the top of the 40 ft. gnomon (now no longer there) and the shadow which it once cast. The top level was known as the Star Observation Platform ... it probably once possessed a thin vertical rod for observations of meridian transits, and the records show that one of the rooms was equipped with a large clepsydra. Below the tower on the north side, lying on the ground and extending for over 120 ft., is the Sky Measuring Scale ... This carries, besides graduations, two parallel troughs communicating at the ends and forming a water-level, and it continues into the body of the pyramid, which is cut away to receive it, so that its base is perpendicularly below the wall of the central chamber of the observatory-house at the top. The gnomon was almost certainly an independent pole sunk into a socket at the near end of the horizontal graduated scale... " I guess that this may be an indication of the origin of the interior straight line in hau tea:

That middle line could be a water channel (dark line) for measuring balance, viz. at noon, the meridian transit of sun. The Sky Measuring Scale is horizontal (female, lying on the ground). Men stand up like a gnomon. But we must leave that aside for the moment. The question in our minds instead should be the Y-sign. One of these mornings I woke up early with an answer to the question of what Y probably is: Earlier I have thought - rather firmly convinced of it indeed - that Y was a sign of dehydrated old 'branches' (presumably indicating winter), and that this was confirmed e.g. by these parallel glyphs:

A 'hand waving goodbye' (meaning 'death') could easily be reformulated as a 'dried branch'. The shape of the 'arms' are similar in these two glyphs, and the difference lies mainly in the design of the 'hand'. I now have changed my mind, and I guess that possibly the designer of the P-text may have misunderstood. First of all because his creation seems to be an unusual type of combined glyph. The normal one ends with Y, not with a hand. There is, however, a similar type of glyph which normally ends with a hand, e.g. (Ga2-15):

where the left part may be a 'fish'. I guess that a 'fish' with head up and tail down is a 'fish' in the daylight, not a 'dead' one down in the deep waters. Therefore it should be allowed to have a hand showing three fingers (in addition to the thumb) - meaning 'fire'. The left part of Pa4-52 and Ha5-10, on the contrary, looks like a moon sickle, a sign of 'darkness'. It is therefore reasonable to let the 'arm' at right end in a stylized 'fish-tail' (meaning 'fish' with head down - a 'dead fish'). I have not only these general remarks to lean upon but - more important - there is evidence in the rongorongo texts showing that the Y-sign might mean 'legs', e.g. in this - I guess - calendar for the week (Ea4-35--Ea5-18):

In Sunday there is a henua dangling from the thumb, in Monday, Tuesday and Wednesday there are Y-signs instead of hands. From Tuesday onwards the legs are like inverted Y:s. From Thursday onwards the Y held high is changed to another sign. Maybe this is a sign for the 2nd phase of the week, expressed by the form of a waning moon? I suggest that there must be an association between legs and Y. The planets should be viewed during the night and when a constellation then rises in the east it is not possible to discern where the horizon is. Therefore the legs above are designed as open downwards. Sun and moon, however, can be viewed during the day and therefore the legs for Sunday and Monday are shown with proper ends downwards. We have already seen that îka may mean a human victim hung upside down in a tree. Head down and feet up means dead, I believe. But then it is understandable that the sun at the time of his death has Y as a sign:

We could without difficulty imagine that the right part of the toga (right) glyph is a smaller variant of tôa:

If legs are upwards in the kingdom of 'death', that is because earth is shaped like a ball and down under people walk with their feet upwards. I remember my astonishment as a child when I learnt that if I dug enough deep I would end up in China where people stood upside down. Having heard about that once, you will never forget it and even as far away as on Easter Island they probably would have heard about it. Travels across the equator would have revealed that indeed it was true, sun being in the north going up at right etc, and perhaps Tane pushing up the sky with his feet (in New Zealand) conveyed that message. The natural way to push up a roof would otherwise be to use your arms. So let us leave Y - at least for the moment and until other ideas about Y may threaten this new explanation. What do the right parts of these two glyphs signify?

We invert the glyphs to see the 'fishes' non-inverted:

Now the 'garlands' are hanging down in a more natural fashion (although on the left side instead of the usual right side). This type of 'garland' (maro) seems to mean 'end', that is a conclusion I have drawn from the rongorongo texts. The month Maro is June, i.e. the time when the old year ends. Possibly 'stop, halt' as an explanation of maroa may have with this to do.

I think we should reason like this: 1. For the daytime periods he said tapa mea, for the nighttime periods he said toa tauuru. Therefore there should be some similarity in meaning between these two expressions. 2. Both tapa and tau have to do with counting periods:

Barthel 2: "The last month of the Easter Island year, 'Maro' (Te Maro, He maro), refers to the feather garlands (maro) the people presented to the king, while the first month, 'Anakena', has the same name as the royal residence, which was the scene of such offerings. 'Maro' and 'Anakena' are closely related, one preceding and one following the change from one year to another. There also seems to be a play on words between 'Maro', the month of the winter solstice, and maru, shadow as in MGV. (compare Hiroa 1938:415)."

"The fact that chickens have the most abundant feathers during the month 'Maro' coincides with the gathering of the people and the offering of feather garlands to the king of the island." What has ended? Presumably the light half of the 'day'. There are no other maro signs in the calendar. Metoro used the word ehu in connection with these two maro-glyphs:

Maybe he meant ashes, referring to the fire of the sun or the fires of the people? Or maybe he meant that we all will finish as dust? Or maybe he meant both? Furthermore: Metoro always said toa tauuru at the tôa type of glyphs in this calendar. Both tau and uru have many meanings and it is therefore not easy to understand what he meant, see for instance about uru:

I suggest that we should reason like this: 1. For the day time periods Metoro used the words tapa mea and for nighttime he said toa tauuru, therefore there should be some similarity in meaning between these two expressions. 2. Both tapa and tau may be used when referring to counting periods:

3. For uru we then should pick out a meaning which harmonizes with counting periods. The key is found in Nilsson's "... It is significant that on the Society Islands the bread-fruit season is called te tau ..." In my Polynesian dictionary I have inserted a hyperlink from uru to this information:

4. We then should note that number 4, connecting both to uru - breadfruit, skull - and to the earth beneath which the sun has sunken, is marked also in the two maro-glyphs:

The 'chicken feathers' are 4 + 4 = 8. And 8 is a sign for the moon (eight periods in a Rapa Nui month), a fact which should be used also for the periods of the night. We have 12 glyphs for the night in this calendar. Is it possible to arrange them into two groups with 4 tôa glyphs in each group?

Clearly we must abolish 2 of these tôa glyphs to reach number 8, and equally clearly it is in the period before midnight where the abortion must be located. I suggest that we should discount nos. 1 and 2. They are equivalents to the 'birth' glyph (Aa1-16) at dawn. 5. While tapa mea means 'reddish count' (or something like that), pictured as the illuminated sky cap, tôa tauuru probably means 'black count' (or something like that), pictured (I guess) as the night sky cup. 6. To see this night sky cup better I think that we should rotate the tôa glyphs 90o around. From this hypothesis it should be possible to explain the glyphs in the night calendar of Tahua. Who was Metoro Tau'a Ure? Can we trust him? What could he have known about the meaning of the glyphs? Although his words are not necessary to reach an understanding of the rongorongo texts, I cannot deny that his words have influence on the translation process. I hope that his influence is similar to a catalyst and that his influence does not misdirect or interferes with my intuition; that instead my intuition will lead. Fischer devalues the words of Metoro, e.g.: "Once Metoro had finished singing - for his 'reading' was done exclusively in a singing voice - Jaussen asked him what it meant (Villeneuve, 1878:837). 'Oh', replied Metoro, 'this is how the priests used to read. I'm reading like them, but without knowing what I'm saying ..." "Metoro informed Jaussen that on the island they had had the custom of getting together in a ring and peforming 'this song' as a sort of cult. Whereupon Jaussen noted Metoro remarking further ... 'Besides the word, there's the proper meaning of the sign; this song comprises a gathering of other words which the artist's imagination had supplied to it and which caused the pupil incomparably more trouble to retain in his memory than the simple meaning of the sign..." It seems that Metoro probably knew the proper meanings of the different types of glyphs, but that he was unable to deliver the meanings added by means of different small signs. On the other hand, I believe that Metoro remembered some of the details involved in e.g. the day calendar. There is evidence that he used information from parallel texts when he 'translated' to Jaussen. If we proceed to the next glyph, Aa1-39, and rotate it clockwise 90o we see:

The fish is swimming left towards west and below him the water forces an appendage backwards. If we hadn't seen a fish swimming like this, it would have appeared wrong to rotate the glyph. The appendage would then had appeared growing upwards. The type of glyph in the appendage Metoro used to call nuku and so he did at Aa1-39 (e ia toa tauuru - no te uru nuku). Maybe te uru nuku should be understood as the black earth, i.e. during the night darkness covers earth. The fish above the appendage may be the dark night sky. But for black (dark, black-and-blue, green) we have another word, uri (not uru). Instead, I guess, we could translate: uru = "To enter, to penetrate, to thread, to come into port (huru); uru noa, to enter deep." Our side of the earth has gone down deep into haven for the night. "haven ... harbour ... rel. to (O) Ir. cuan curve, bend, recess, bay = Gael. cuan ocean..." (English Etymology) Of course this must also influence the reading of toa tauuru: not 'black count' but the 'count for haven'. And if so, then we should change 'red count' into 'count for heaven'; the word 'heaven' implying light - the roof of the sky after darkness has (been) lifted from earth. As to nuku we should remember: "They were Ranginui, the Sky Father, and Papatuanuku, the Earth Mother, both sealed together in a close embrace." The Earth Mother has her back (tu'a), a flat surface (papa), upwards, and her face downwards. We should understand nuku to mean earth. I cannot find the word nuku in the Rapanui wordlists, but it is a Polynesian word:

If the little circle (on the nuku part of Aa1-39) is an eye, with the meaning 'face' (mata) we can imagine that it is Papatuanuku who is depicted (with her face downwards).

But then we should reconsider the noon type of glyph:

The two ears / eyes may mean that there are two faces, one in each direction, presumably one face for a.m. and the other for p.m. In Aa1-40 there are no appendages:

But the fish has grown thicker, a tendency which increases until midnight:

I guess we should understand this to mean that darkness is thicker around midnight.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||