|

TRANSLATIONS

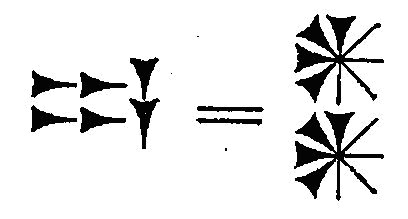

It is necessary never to stop 'piling up and tie together' new phenomena from the 'myriad' never ceasing to appear. The presentation above of the e.m. glyphs makes me notice that there seems to be a relationship between the form of tapa mea in P and the form of the glyph type presumably illustrating the ways of the sun:

In general, the tapa mea glyphs in P are similar to those in A, i.e. they are convex in both directions. There is an explainable exception in the 2nd e.m. period because there the horizon in the west presumably is shown as a straight vertical line. This line is a kind of demarcation line, which also is used at dawn in Q and P and at noon in H:

In P the 3rd period is equidistant from noon compared to the 2nd e.m. period (5-3 = 8-6), i.e. the horizon in the east is located equidistant from noon compared with the horizon in the west. This phenomenon (oval tapa mea in P) seems to be connected with the phenomenon of absent tokorua. Instead of tokorua with wedges (as in H) we have sun rays. Though even in P we have tokorua during a.m.:

These tokorua are without wedges, i.e. they should be read differently than if they had wedges. Possibly they represent 'staffs' (instead of - presumably - the path of the sun across the sky from the mountain in the east to the mountain in the west). I have earlier proposed that the concave (not oval) type of tapa mea represents the crust of the earth. To see this the glyph should be turned 90o around counterclockwise. The oval type of tapa mea instead may include also the back side of the earth. Does this new phenomenon (of a correlation between the appearance of oval tapa mea and the absence of tokorua with wedges) change the earlier ideas? I think an explanation should be searched for and that a possible understanding might be reached by considering the possibility that a straight horizontal line in tapa mea would in some way interfere with a wedge in tokorua. Yesterday I couldn't get any further along this trail of thought. I went to bed still thinking about the problem. During the night I woke up and had the solution: They interfere because they describe the same thing. In tokorua the wedges illustrate the mountains at the horizons in the east and in the west, in tapa mea the straight vertical line depicts the straight horizon - no mountains there! This explanation means that my earlier interpretation of tapa mea as the crust of the earth must be wrong. Certainly this glyph type should be turned around 90o counterclockwise, but as the straight bottom part (after that rotation) shows the horizon then the upper part cannot be the surface of the earth. I still believe that the short straight lines mean light rays, but they do not reach down to the surface of the earth, they are instead located to a higher level.

If the glyph at left (Qa5-42) illustrates the horizon in the east and the red light appearing at dawn and if the glyph at right (Qa5-50) shows the view later on in the day, then obviously this bent shape with short straight ray marks must be the sky roof. Above the sky there is water and water extinguishes fire. Therefore this light (= fire) must be found on another lever than the water. The sky is light blue and that seems to imply that this fire level is higher up than the water (the light shimmering through the water) . But according to the view of the Babylonians the sun disappeared through a door in the west in the evening and travelled across the sky above to enter next morning through a door in the east, which means that this passage above the water inhibits the light to reach down to us on the surface of the earth. Presumably, though, the inhabitants on Rapa Nui knew that the sun revolves around the earth and takes another route (under us instead of above us) during the night. Thus the old knowledge about a passage for the sun above us might have been used to explain how the sun went from east to west during the day in spite of there being water in the sky. He sails across this water and therefore there is light above the water. "Two men came to a hole in the sky. One asked the other to lift him up. If only he would do so, then he in turn would lend him a hand. His comrade lifted him up, but hardly was he up when he shouted for joy, forgot his comrade and ran into heaven. The other could just manage to peep over the edge of the hole; it was full of feathers inside. But so beautiful was it in heaven that the man who looked over the edge forgot everything, forgot his comrade whom he had promised to help up and simply ran off into all the splendour of heaven." (Arctic Sky) Feathers symbolize light/fire. Possibly the short marks on top of the convex sky roof in tapa mea depict feathers. We now have to check for evidence which supports or undermines the new view of what tapa mea means: 1. In Q we find these instances with wedge and / or straight vertical line:

2. In H we have:

3. In P we have no wedges and only two (dawn and evening) vertical straight lines:

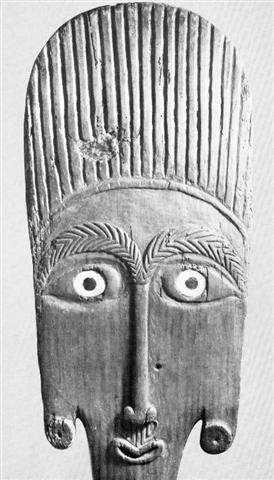

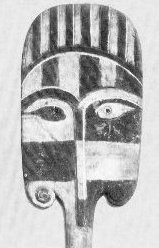

Evidence show a slight favour for the new ideas being valid. Especially the '6th' period of H seems impressive: a straight vertical tapa mea line which means noon cannot interfere with a wedge (because these wedges are located at the horizon). The oval tapa mea in A shows (I think) both the day side and the night side of the sky. Rongorongo glyphs only exceptionally have internal signs, they delineate circumferences. Therefore oval tapa mea does not show the earth. Consequently we have not only changed the interpretation of the bent (non-oval) tapa mea from a picture of the earth to a picture of the sky, but also changed the interpretation of oval tapa mea from a picture of earth and underworld to a picture of day sky and night sky. As the wedge-sign in a preceding glyph presumably refers to a mountain at the horizon (a part of the earth) it seems never to be used together with an oval tapa mea. Metoro's words tapa mea refers, I believe, to the uplighted sky roof. I also believe that the top of an ao paddle is a similar picture of this uplighted sky roof (picture from Heyerdahl 3):

The hair is depicted with straight marks, whereas the bent eyebrows have wedges (signifying 'female'). "When the stars fade away and disappear, it is ao, daylight ..." That statement was from Hawaii. On Rapa Nui the meaning of ao seems to have been inverted, perhaps because there the equator is in the north (summer months on Hawaii are winter months on Rapa Nui and vice versa):

Reversals of meaning may happen from other causes too (than travelling across the equator). Churchill 2: "Daytime is life time, its joys are joys only when the eye can see clearly. When the shadows snap suddenly upon the swiftly fading glow of the sunset the cruel gods are abroad, man in black terror cowers with his kin in a gloomy home about the fat smoke and dull glow of his string of kindled candlenuts. From the dusk of evening until the eastern gleam he will not venture from his shelter except that, under the pricking of his seatomantic [?] dread, in some middle hour he slinks out under the wheeling stars and to the beach where in the darkness and the swirl of the tide not even the whistling gods may see that which might work him harm. Man may live heedless days, but when it comes to the reckoning it is the nights he counts, the nights lived through. Here, there, and well nigh everywhere in the Pacific world, po as night means calendar day. The Maori goes yet farther: po may mean to him a season, it may mean the obscurity of eternity." In Churchill 2 we also find another interesting word, ahi, mentioned: "Maori and Tahiti are the only languages in which au means smoke; in each it means vapor in general, each employs more freely a definitive compound, and Maori has several other words for smoke. Having expanded in significance to mean vapor in general, the only way in which it was possible to make it plain when smoke alone was meant by au was to make the definitive compound fire-vapor auahi. This we find in Maori, in Mangareva, in Rarotonga to mean smoke. In the Marquesas this too means vapor as well. By an odd mischance in Tahiti auahi passed from the smoke to the fire itself, and to designate smoke it became necessary to cry back once more to au and devise au auahi. We have seen that in the Marquesas auahi means vapor as well. Passing thence to Hawaii we find that auahi has lost even the memory of the fire and it has broken down in form to uahi, used for any vapor." The fire (ahi) and the smoke (au) from the fire are connected, like the brothers Quetzalcoatl and Tezcatlipoca. Fire is ignited, it burns, it changes into hot glowing coals and after that we have ashes and smoke. Soot there was on one of the breasts of Sister Sun: "Her cooking pot always hung over her qulliq. When her attacker came again, she reached out and tried to touch the pot but her lamp was out and it was completely dark. Finally she managed to touch the pot. She then wiped her sooty hands on the face of her aggressor. After she had been molested once again the aggressor left her igloo. She followed him to see where he would go, hoping to finally find out who he was. She saw him going to the qaggiq where the festivities were being held. As she neared it she could hear people laughing. Someone was saying: 'Taqqiq inutuarsiurasumut aasit naatavinaaluk'. - Taqqiq (the Moon) has been marked with soot as he has again been looking for someone who might have been alone. So Siqiniq entered the qaggiq and saw that her brother's face was covered with soot. Embarrased and angry, she took her breast, cut it off and offered it to her brother saying that, as he liked all of her so much, why not eat her breast as well." (Arctic Sky) Perhaps we may now make a preliminary summary of the menaing of the different variants of the tapa mea type of glyph:

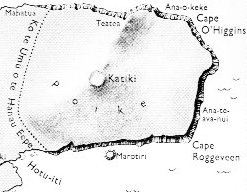

From the new perspective, where tapa mea is seen as the sky rather than the earth, there are certainly many new angles on all that has been said earlier about the meaning of the rongorongo texts. But we cannot stop here and revise everything written, instead we have to move on. Talking about perspectives: close to the polar circle (Sweden) we look for the sun in the south. On Easter Island they looked in the east, there 'orientation' meant looking eastward. The dream voyage of the kuhane of Hau Maka reached the most easterly point at Poike (also the highest point). As a result of the earlier investigations into this subject we know that this highest and most easterly point coincided with 'midsummer' and that after 'noon' the sun (and the kuhane) moved (declining) towards west. At the highest point in the banana plantation of Ure Honu there was a hole with the skull of king Hotu A Matua. And "... the sun was standing just right for Ure Honu to clean out ..." During the night a rat showed him the hole and this rat was "a spirit of the skull (he kuhane o te puoko)". Could this hole be Pua Katiki?

We could also ask ourselves how the features of a landscape (map) in a face, e.g. that on the ao paddle, correspond to 'noon:

In the middle of a face we find the nose, which also is the feature closest to the observer. And there is a hole in the form of a mouth. Indeed, the form of this ao mouth resembles a type of glyph:

Though this glyph must be turned clockwise to fit, presumably because the mouth is 'female' (moon descends in the east, not the west). The ao nose is strangely long and thin (ihu roroa), giving the impression of being designed to look like a tree, from the 'nut' at bottom and up to the two (palm?) branches shadowing the eyes. If number 2 symbolizes 'female', then both the eyes and the branches are 'female'. But the 'palm' tree is male, from hua upwards, and probably born from the 'female' mouth below. The ears are pendant and have what looks like sun symbols inserted into the holes. Though this face is symmetric there seems to be a little sign in the left (right from us seen) eye: a triangular form which I think has a meaning reminding us about how Ure Honu lifted up one half of the hare paega of Tuu Ko Ihu. In the 'face' of another ao the play between darkness ('female') and light ('male') is more clearly illustrated:

Though for some reason it is the right (left from us seen) eye which is black. Right should be 'male' and correspond to the light a.m.-sun in the south, one would think. However the reason behind this inversion presumably is that we here see a female head. Moon is a better illustration of the play between dark and light than the sun, which is the image of stability. We can count to 7 white and 7 black 'rays' on the top of her head - she must be a personification of the moon. If white is male and black is female, and if an odd number is male and an even female, then we could say that we have a binary play between the sexes: 1 is for the man and 0 (not 2) for woman. That zero is the mouth in the first example of ao above. Moon has both black and white, man only white. In his world, therefore, woman is needed to represent black. If we make holes in our ears (to carry some object, like a sun symbol), then we have ears with 2 holes, one from the time of birth and the other a later fabrication. The hole from our birth is dark and surrounded by a pattern like the 'spring of a watch': "The chief Ear Ornament is the white down of feathers and Rings which they wear in the inside of the hole made of some elastick substance, roll'd up like the spring of a Watch, I judged this was to keep the hole at is utmost extension." (Beaglehole) This seems to be another reason (in addition to 'keep the hole at is utmost extension') why there should be a similar pattern in the fabricated hole. I suggest that the natural holes in the ears are in principle 'female' (dark and like zeros) and that therefore the spiral pattern also became 'female'. Indeed, we can see that the fabricated holes in the ears of the moon ao above have spirals inserted:

On the other hand, sun symbols - e.g. such as illustrated in the ears of the first ao above - can have no such spiral symbol:

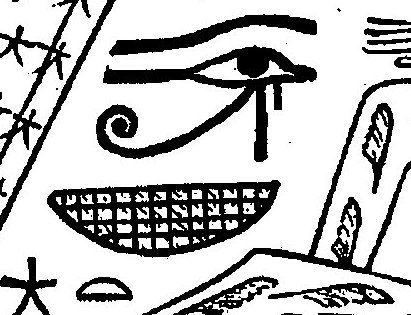

Because the sun should never 'go down', 'disintegrate', 'be swallowed' in a hole. He should never be drawn down into some swirling watery abyss. He should instead fly high with his 'white down of feathers'. In Babylonia sun went out through a door in the west to reappear half a day later in the east after having travelled securely above our heads. Possibly the extra sets of holes in ears were initially made to picture how sun went out one way and we other mortals through another exit. Or perhaps sun had two doors and moon two other doors. In Egypt - I suspect - they had another type of safety arrangement, a net in the west to catch the sun before he perished:

And then, in the morning, the net had been converted to a basket for delivering sun again in the east:

Let us now enlarge that left 'half in shadow' eye of the first ao:

I don't think the vertical line is a natural crack in the wood - it does not stretch outside the eye area. Also the impression is that the triangular area is higher than the corresponding area in the right eye. I guess the interpretation of this message is that the left eye is 'threatened' by darkness. (No wonder the eyes look worried.) In the picture from Egypt showing the basket at dawn there is a wedjat sign.

According to Wilkinson very early sun and moon were understood as the eyes of the falcon god Horus. Later these eyes became differentiated and sun became the right eye (the eye of Ra), while moon became the left eye (the eye of Horus).

At left (from us seen) the eye of Ra at right the eye of Horus (pictures from Wilkinson). We are now beginning to understand. The triangular area in the left (e.m.) eye of the ao above indicates that sun is 'under' (the dominion of) the moon. Three (as in triangle) is an odd number, but anyhow firmly in tradition connected with moon. This we can see also in the eye of the Horus-picture, where there are three persons in the black moon circle. Maybe we should guess that the first glyph during the e.m. period (a compound glyph with parts from sun, hau tea and a grownup person) has two 'sun'-symbols in the 'ears' to show both sun eye and moon eye?

In H and P (at left resp at right) it looks as if the glyphs are unfinished or a part cut away, i.e. a phenomenon similar to the Y-signs in the two surrounding sun-glyphs:

The central top flame has been converted into a sign of darkness - I interpret Y as a sign of darkness. But if such Y-signs are 'open', then the association will be that also 'open' (unlimited) means darkness. Sun after noon is somewhat dark. The middle glyph, a variant of hau tea with double 'ears', makes me think about Mount Teatea (double tea), as the kuhane station immediately after the noon station Pua Katiki. Therefore I use my index and search for the word 'teatea'. The first (and only) hit from this automatic searh seems promising: "Several hundred Rapanui - probably members of the Koro 'o 'Orongo tribe of the eastern 'Otu 'Iti - observed the ceremony not far from Poike's parasitic cones Parehe, Teatea, and Vai 'a Heva, on the tops of which the Spaniards had planted three crosses. Following three boisterous 'Viva el Rey!' for each cross, the land party let off three salvos of musketry, whereupon the two Spanish vessels San Lorenzo and Santa Rosalia responded with 21 cannon salutes." (Fischer) What are then the meaning of the words 'parehe' and 'heva'? Using Vanaga and Churchill to update my Polynesian dictionary solves this little problem:

I think these meanings fit in very well with the ideas about after noon sun: He has fallen somewhat to pieces (because of his initiation at noon, because he has seen himself in a mirror, because he has met woman etc) and he is not quite himself, out of order. As to the word 'teatea' Churchill served us with these items: "... teatea, white, blond, pale, colorless, invalid; rauoho teatea, red hair; hakateatea, to blanch, to bleach ...arrogant, bragging, pompous, ostentatious, to boast, to show off, haughty; hakateatea, to show off ..." And 'tea' (in single version) means (among other things) 'to rise (of the moon, the stars)' - according to Vanaga - i.e. no connection with the rising of the sun. A curious further note about parehe (from Churchill): "Tapa mahute, piece of mahute material; this term is very common nowadays, but it seems probable that it was borrowed from the Tahitian in replacement of parehe mahute ..." Possibly, in some way parehe may be connected with the general concept tapa:

Metoro's tapa mea is not mentioned here. Maybe we should not translate mea as 'reddish', but instead as 'other', i.e. tapa mea would mean something like 'a separate item (to count?)'.

We leave this trail for the moment and go back to what is the main subject, what happens to the sun when he reaches the horizon in the west? The Chinese might give us help to answer that question. I have discovered that one of their most ancient cosmic models (according to Needham 3) was similar to the ancient Babylonian view:

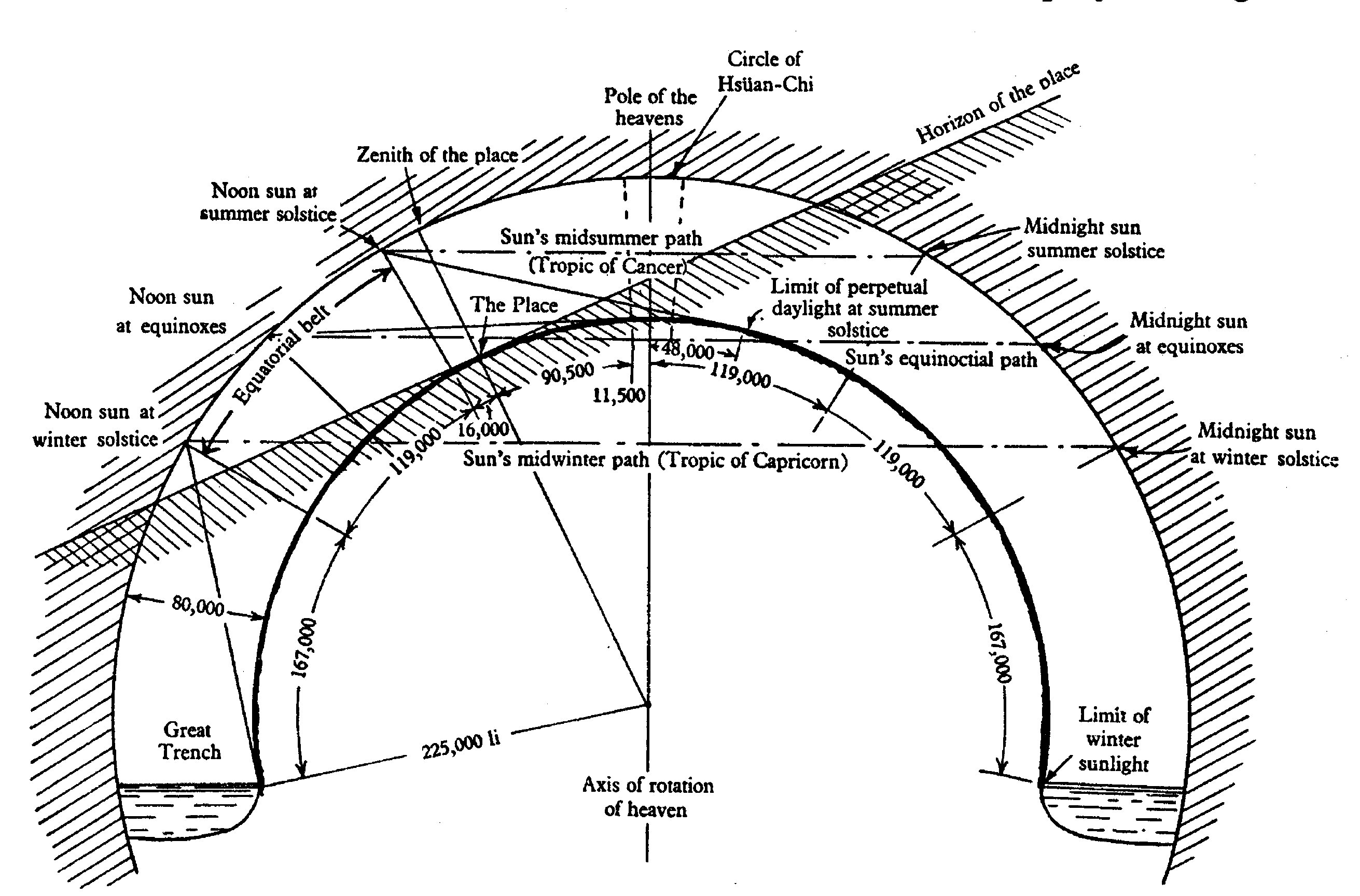

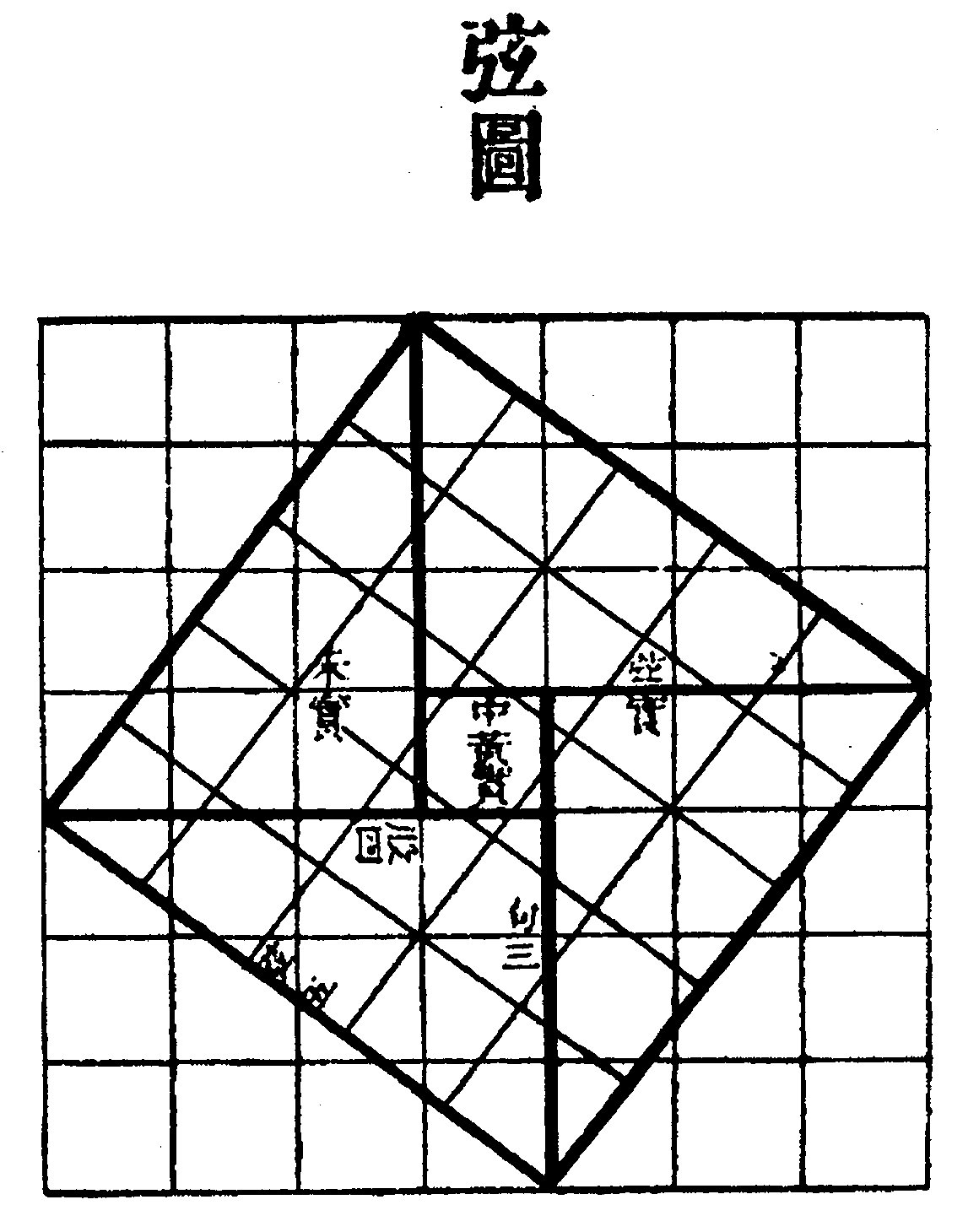

"A detailed study of the Kai Thien universe has been made by Chatley (11) based on the measurements and calculations given in the Chou Pei Suan Ching. "Chatley and others have believed that for the Kai Thien cosmologists the sun itself moved in right ascension and declination, making sudden jumps from time to time; the existence of the ecliptic being ignored or denied. Whether this was really their view seems rather difficult to substantiate, but the ideas of some of the Old Babylonian astronomers before about -500 may have been quite similar." His diagram is reproduced here ... As he says, there is just enough physical truth in the scheme to render it acceptable to very archaic geometers having little more than the Pythagoras theorem at their disposal. One's impression of its antiquity is strengthened by the circumstance that a similar double-vault theory of the world existed in Babylonia ... It would have been one of the culture-traits which passed both westward to the Greeks and eastward to the Chinese, to be developed later in both civilisations into the theory of the celestial sphere. Rather characteristically Chinese, however, was the insistence that the heavens were circular and that the earth was square, an idea which would arise naturally enough from the circles of the celestial sphere on the one hand and the four cardinal points of earthly space on the other ..." Lots of important stuff here. To begin with, they had their own theorem of Pythagoras, not as a truth of strict logic but as a better proof - what is evident for your own eyes:

"(1) Of old, Chou Kung addressed Shang Kao, saying, 'I have heard that the Grand Prefect (Shang Kao) is versed in the art of numbering. May I venture to enquire how Fu-Hsi anciently established the degrees of the celestial sphere? There are no steps by which one may ascend to the heavens, and the earth is not measurable with a foot-rule. I should like to ask you what was the origin of these numbers?' (2) Shang Kao replied, 'The art of numbering proceeds from the circle ... and the square ... The circle is derived from the square ... and the square from the rectangle (lit. T-square or carpenter's square ... (3) The rectangle [carpenter's square] originates from (the fact that) 9 x 9 = 81 (i.e. the multiplication table or the properties of numbers as such) ... (4) Thus, let us cut a rectangle (diagonally), and make the width ... 3 (units) wide, and the length ... 4 (units) long. The diagonal .. between the (two) corners will then be 5 (units) long. Now after drawing a square on this diagonal, circumscribe it by half-rectangles like that which has been left outside, so as to form a (square) plate. Thus the (four) outer half-rectangles of width 3, length 4, and diagonal 5, together make ... two rectangles (of area 24); then (when this is subtracted from the square plate of area 49) the remainder ... is of area 25. This (process) is called 'piling up the rectangles' ... " (Chou Pei Suan Ching - 'The Arithmetical Classic of the Gnomon and the Circular Path of Heaven') Back to Kai Thien ('Heavenly Cover'): "The heavens were imagined as a hemispherical cover, and the earth as a bowl turned upside down, the distance between them being 80,000 li, thus making two concentric domes. The Great Bear was in the middle of the heavens and the oikoumene of man in the middle of the earth. Rain falling upon the earth flowed down to the four edges to form the rim-ocean ..." "The shape of the heavens is lofty, and concave like the membrane of a hen's egg. Their edges meet the surface of the four seas (the rim-ocean). They float on the yuan chhi (primeval vapour). It is like a bowl upside down which swims on water without sinking because it is filled with air. The sun turns round the pole, disappearing at the west and returning from the east, but neither emerges from nor goes below (lit. enters) the earth." (Chhiung Thien Lun - 'Disourse on the Vastness of Heaven') Well now, this is a new key idea for understanding where sun goes after disappearing in the west - he does not go by some invisible channel across our heads but simply is hidden by the 'mountain' of the earth dome. His movement is not suddenly upwards across and behind the sky, but he continues his path outside our view. "According to the Chou Pei, the sun could illuminate an area only 167,000 li in diameter [radius according to the picture of Chatley above]; people outside this would say it had not risen, while those inside would be enjoying daylight. The sun was thus regarded essentially as a circumpolar star, illuminating continually one or other part of the earth's surface as if by a kind of searchlight-beam. But its distance from the pole varied according to the season as it followed one or other of the roads ... between seven parallel declination-circles ..., the outermost being that of the winter solstice and the innermost that of the summer solstice ..." With 7 circles there will be 6 routes between them. Is that the reason why sun has 6 double-months in a year and we have a week with 7 days? The tapa mea glyph type presumably is a similar double-vault image, 'Heavenly Cover' (Kai Thien). The hatchmarks in Chatley's reconstruction (see picture above) are - I believe - drawn for easier 'reading'; a straight line for the horizon has hatchmarks below and outside the sky circle there are also hatchmarks, in both cases with the reasonable interpretation 'not visible'. The tapa mea has not really hatchmarks, but the (usually 6) marks at right (= on top) of the glyph could also mean 'not visible' (instead of as I have suggested earlier: 'fiery feathers'). Still - such a glyph type as that represented by Gb7-11:

makes me continue to believe that these marks are representations of feathers (probably the glyph type shows a chief, ariki). And feathers may convey a sense of 'do not look!' (i.e. 'not visible' in a slightly different sense). "Like the sun, chiefs of the highest tabus - those who are called 'gods', 'fire', 'heat', and 'raging blazes' - cannot be gazed directly upon without injury. The lowly commoner prostrates before them face to the ground, the position assumed by victims on the platforms of human sacrifice. Such a one is called makawela, 'burnt eyes'." (Islands of History) The tapa mea glyph type has not two concentric half-domes (as in Chatley's reconstruction), but they should not be concentric and they should not be half-domes: "The eye sees the cloudless sky not as a hemisphere, but as the cap of a sphere; the zenith appears nearer than the horizon." In my mind two tapa mea glyphs revolve:

The flatness at (e.g.) dawn may mean that the horizon is far away, while the vault of the sky is just above the head. The straight line (in after noon - the upper part of Ha6-11) is like a radius, a measurement, an artefact just as well as a hare paega (the image of the night sky), long but not very far to the roof. But a straight line is also generated by light rays, which implies that the border between light and dark will also be a straight line. I imagine this is a better explanation for the straight half of the line in Ha6-11 (and in Ha6-14). Islands in the Pacific usually are divided into a dark western half and a light eastern half. So it was on Rapa Nui too, where the dark side dominated - as also was usual in the Pacific in general (not only Polynesia). I have guessed that this idea once was generated in South America where the dawn sun lit up the eastern sides of the mountains far ahead of the valleys on the western side. But now I believe that it was an idea common to all mankind from the very beginning. The example from Egypt is evidence - the left eye of the sun ('Horus') was dominated by the moon. However, there is a problem. Left means west if you are looking towards north (as when the location is south of the equator), but Egypt lies north of the equator and they should reasonably have their faces towards south. The pattern left - darkness is understandable if you live south of the equator, but not if you live north of the equator.

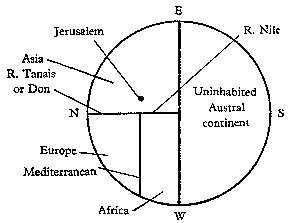

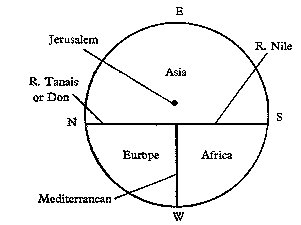

Once again we have arrived at the problem

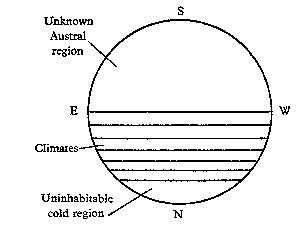

of orientation. In Needham 3 he has made schematic

drawings over the types of old European maps:

East or south are the usual choices when you turn your face to orient yourself (at least when you live in the north). However in Egypt they oriented themselves in another way:

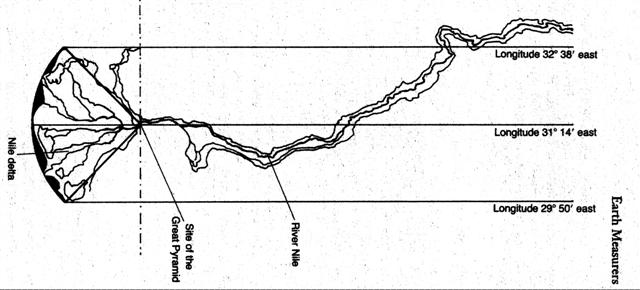

The Egyptians regarded south as 'up' and north as 'down' on the map, the delta being the lowest part of Egypt. And the division of their country into two rectangular shapes was made with the Nile like the equator in the middle. Although the Nile is perpendicular to the equator. Egyptians do it differently. Each of these two strips measures 7o in length and 1o 24´ in breadth. The ratio is 5. We would then expect to find 2 * 5 = 10 as the area for such a strip (if 10 is the base of counting), but the area is only 9.8 square degrees (= 7 * 1.4). Should we include the borders to reach 10? Anyhow, the home country (henua) of the Egyptians has a shape like the tropics, with the Nile being the equivalent of the equator and with the eastern and western borders equivalent to the 23½ degrees limits of the sun. Like three fingers the borders and the central line determine their henua. But the Egyptians used to divide their country into lower and upper Egypt, not this way. That the Nile is the navel string, umbilicus, is however very clear. "Let us now return to our map, which also incorporates a triangle representing the Delta. Its other main components are the three parallel meridians. The eastern meridian is at longitude 32o 38´ east - the official eastern border of Ancient Egypt from the beginning of dynastic times. The western meridian is at longitude 29o 50´ east, the official western border of ancient Egypt. The central meridian is at longitude 31o 14´ east, exactly midway between the other two (1o 24´ away from each). What we now have is a representation of a strip on the surface of planet earth that is exactly 2o 48´ wide. How long is this strip? Ancient Egypt's 'official' northern and southern borders (which bore no more relationship to settlement patterns than the official eastern and western boundaries) are marked by the horizontal lines at the top and bottom [rather bottom and top, I think] of the map and are located respectively at 31o 06´ north and 24o 06´ north. The northern border, 31o 06´ north, joins the two outer ends of the estuary of the Nile. The southern border, 24o 06´ N, marks the precise latitude of the island of Elephantine at Aswan (Seyne) where an important astronomical and solar observatory was located throughout known Egyptian history. It seems, that this archaic land, sacred since time began - the creation and habitation of the gods - was originally conceived as a geometric construct exactly seven terrestrial degrees in length. Within this construct, the Great Pyramid appears to have been carefully sited as a geodetic marker for the apex of the Delta." (Hancock) If we eliminate the watery (female, dark etc) etc estuary, we arrive at a resemblance with this glyph (Qa5-45):

Coincidence? Perhaps. More fundamental, though: the Egyptians regarded 'up' as away from the water, a very reasonable idea (as water flows downwards). On Easter Island down therefore was in the west, and the names given by the kuhane of Hau Maka makes that very clear: "If one examines the list of place names of localities, it becomes apparent that they are grouped into pairs according to the proximity of location or the similarity of terrain. The twenty-eight names are arranged in fourteen pairs. The first step in the reconstruction of the compositional scheme shows the following groupings:

The vertical columns represent opposites according to their color attributes. If we consider only those color attributes that are listed twice, we come up with the contrasting pair uri (3 and 5) vs. tea(tea) (14 and 18). Dark vs. light (or black vs. white) is a contrast pair that was used poetically in eastern Polynesian figures of speech (so-called stereotype parallelism) ... The grouping according to colors definitely seems to be planned. The list of names of localities is divided into two subseries of unequal length. While the first twelve pairs (reading horizontally) are topographic stations along the dream soul's path in search of the future residence of the king, the last two pairs represent places of political importance (25 and 26 are the residences at Anakena of the current king; 27 and 28 are the residences of the future king and of the abdicated king). If one traces this path on a special map of Easter Island, the following pattern emerges, based on the direction in which the dream soul travels: eight pairs of names make up the stretch from west to east; one pair marks the segment from south to north; two pairs indicate the path from east to west; and, finally, another pair marks a second segment from south to north. In both cases, the (relative) 'cross segments' (17 and 18, and 23 and 24) are pairs of mountains." (Barthel 2) "Number 1 indicates rocks in sea water; number 2 is a hole in a rock, filled with sea water. In the case of this pair, we are dealing with an inversion of the theme 'sea water'. Number 3 is the crater that is always filled with fresh water; number 4 is a side crater, occasionally filled with rain water. The general theme of the second pair is fresh water as a constant supply (the crater lake) and as a temporary supply (rainfall). The first parts of both pairs are far superior to the second parts, both in quantity and quality." (Barthel 2) The 'dark' side is superior to the 'light' side. But both sides start at the bottom and go upwards, as in Egypt. I remember that the burial sites were located on the west side of the Nile. There is a tendency for 'dark' to mean 'old'. The firstborn son of Hotu A Matua inherited the west side of the island. Does that mean that a straight line (as in Ha6-11 and Ha6-14) means superior? Strangely, though 'superior' means 'over' while 'inferior' is 'below', and therefore Poike ought to be 'superior' while the opposite west coast of Easter Island should be 'inferior', that was not the case. But maybe 'upper / lower' is another concept than 'superior / inferior'? The hau tea type of glyph:

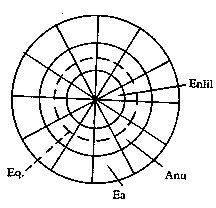

perhaps is originating from the Chinese (and ultimately Babylonian) concept of the paths of the sun. "... distance from the pole varied according to the season as it followed one or other of the roads ... between seven parallel declination-circles ..., the outermost being that of the winter solstice and the innermost that of the summer solstice ..." "Chatley and others have believed that for the Kai Thien cosmologists the sun itself moved in right ascension and declination, making sudden jumps from time to time; the existence of the ecliptic being ignored or denied. Whether this was really their view seems rather difficult to substantiate, but the ideas of some of the Old Babylonian astronomers before about -500 may have been quite similar." 7 (dark) lines for the sun to jump over (just as at noon) and 6 paths to advance along. But originally there perhaps were only 4 lines and 3 paths: "Assyriologists have long been familiar with a number of cuneiform tablets which were preserved in the library of King Assurbanipal (Ashur-bāni-apli, -668 to -626) at Nineveh, but which date as to contents from the late -2nd millenium. These show diagrams of three concentric circles, divided into twelve sections by twelve radii. In each of the thirty-six fields thus obtained there are constellation-names and certain numbers, the significance of which has not yet been explained ... Much light has been thrown upon the diagrams by modern attempts at reconstruction and interpretation. Could they not be regarded as primitive planispheres, showing both the circumpolar stars and the equatorial 'moon-stations' corresponding to them? Such a view seems to be supported by the most recent researches. The tablets with 'planispheres' belong to the class now known as that to the 'Enuma (or Ea) Anu Enlil' series. The corpus contains some 7000 astrological omens, and the time of its formation was contemporary with the Shang period, i.e. from about -1400 to -1000. The planispheres consist of 'three roads', each marked with twelve stars, one for each of the months according to the time of their heliacal risings. Those of the central road, the equatorial belt, were known as the Stars of Anu; those of the outer road were asterisms south of the equator (Stars of Ea), while the inner road was travelled by the northern and circumpolar asterisms (Stars of Enlil).

After this time the planispheres are no more seen, but their place is taken by lists of stars, modified and much improved, on the tablets of the 'Mul-Apin' series (c. -700).d Thus eighteen star-gods were supposed to be always visible at one time. d So called because one of the three lists begins with the 'star' (mul) Apin, i.e. a constellation composed of γ Andromedae and stars in Triangulum. The Chinese also recognised this group, as the 'Great general of the heavens' (Thien ta chaing-chün) ... he set heliacally in autumn, the season for punishments ... " (Needham 3) I think that over time things always become more and more complicated, until some kind of 'revolution' throws it all out. A new beginning from scratch (although with some experience still left from the old mess) is then given hope. Therefore, I guess that at first there was the primary distinction only, the distinction which must be true because it was immediately defined by the eyes (the organ of truth): light contra dark. This primary distinction would then be used to define day and night and the twin concept summer and winter. The day / night idea illustrated the somewhat more difficult to grasp concept of summer / winter, that I believe. Two season only at the start. Transposed to the sky and the pheonomenon of the sun this would imply the paths of summer and winter, with 'jumps' across the dividing line at the equinoxes. The hau tea glyph type maybe is an illustration of this polar division of the sun path over the year:

Two lanes of light and in between the 'equator', the dividing line. In China they had trigrams before the hexagrams. Maybe yet earlier they had just two sticks to toss into the air in order to see what pattern developed when they landed on earth, what pattern would determine the future. In the calendar of the day this type of composition is found:

Presumably the upper part is a variant of hau tea with two 'eyes' (in contrast to the normal glyph with one only, located at the upper right corner):

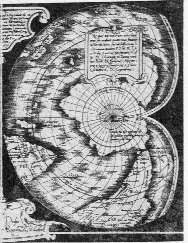

I guess the right 'eye' is summer sun and the left 'eye' winter sun. In the day calendar the right 'eye' would then be reflected as a.m. sun and the left 'eye' as e.m. sun. Though at the same time the right 'eye' would be sun and the left 'eye' moon. Before leaving the subject of maps I must insert another one which caught my eye:

It was drawn by Mercator, "showing Antarctica's mountains and rivers covered by ice" (Hancock) A remarkable map from the sixteenth century considering that Antarctica still hadn't been discovered. The other remarkable thing is that this map projection is similar to the 'mouth' glyph (cfr the first mentioned ao earlier):

The similarity would perhaps not be very remarkable in itself, but earlier I had begun to suspect that this glyph type was designed to represent the path of the sun (or moon). The indentation at left would then indicate winter solstice or the dark period of the moon. Then back to Babylon. In Jenssen is documented (in his cryptic cumbersome style) that Ea was not only a god but also a star: ”Ist nun der Bīl des Schöpfungsberichtes im Norden im Pol des Aequators zu suchen, so dürfen wir, wie schon bemerkt, Ía im Süden suchen, natürlich nicht in unserem Südpol, da ein solcher Himmelspunkt für die Babylonier nicht existierte, sondern in einem möglichst südlichen Punkt am Himmel, in einem Punkte oder Stern der sich etwa nur wenig über den südlichen Horizont erheben konnte.

Während

Bīl als der himmlische Bīl nur in Verbindung

mit Anu als

MUL

= Stern bezeichnet wird, allein aber nur als Da es jenseits des Horizontes für den Babylonier keinen Himmel gab, so kann der astronomische Ort des Ía auch nicht in einem nur gedachten Punkte, dem mathematischen Gegenpunkte unseres Nordpols, des Bīl, gesucht werden; denn Ía steht ja nach dem Schöpfungsbericht … am Himmel! … Dieser Gottstern Ía ist sicher identisch mit dem Stern von Íridu (MUL-NUN-KI) … Denn, wie … die Beobachtung, dass ein Stern des Himmels míšha imšuh (= einen besonderen Glanz entfaltete), der Beobachtung folgt, dass ein solcher ādir war, so folgt an unserer Stelle die Angabe, dass der Íridustern míšha imšuh, der, dass der Gottstern Ía ādir war. Diese Identification der beiden Namen wird aber so gut wie gewiss durch … wo der Íridustern als Synonym von dem Stern Mu-sir-a-ab-ba genannt wird, dessen Name ‘Mütze oder Haube (?) des Meeres’ … direkt auf die Mu-sir-kišda d. i. Haube (?) (des Himmels) = Anu als Gegensatz hinweist. Ía ist ja aber bekanntlich Herr und König des Meeres, dieses liegt im Süden von Babylonien, Íridu liegt im äussersten Süden Babyloniens und Ía’s ’Ort’ am Himmel liegt im Süden …” ”… finden wir nur folgende drei an und für sich in Betracht kommende Sterne: 1) ο Ceti = Mira (Ceti) … 2) α Orionis (= Betelgeuze … 3) η Argus … Von diesen drei am südlichen Sternhimmel befindlichen Sternen sind aber sofort auszuscheiden ο Ceti und α Orionis, da sie zu wenig südlich stehen, um als Meerstern = Íastern gelten zu können. Bleibt also nur η Argus, der zu der Zeit, wo die in Rede stehenden Aufzeichnungen und Beobachtungen gemacht wurden (etwa um 700 vor Christi Geburt), zu einer Zeit, wo der Südpol des Aequators sich in der Nähe der kleinen magelhaensschen Wolke befand, eben über dem Horizonte von Babylon sichtbar war. Dieser Stern verändert … bisweilen ganz plötzlich seine Helligkeit … und ist … schon (oftmals) fast dem Sirius oder α Centauri gleich an Helligkeit, ja heller als Canopus gesehen worden. … Was mir aber von Allem noch sehr für meine These zu sprechen scheint, ist, dass er zum Sternbild der Argo gehört, während das Schiff ein Symbol des Ía war.” According to Jenssen in old Babylonia they had a more limited sky world than that of King Assurbanipal. There were the two north pole localities, Anu and Bīl (pole of the ecliptic respectively pole of the equator, and Ía as some kind of opposite in the south, but not as a south pole in our terms. More to the point: "... wo der Íridustern als Synonym von dem Stern Mu-sir-a-ab-ba genannt wird, dessen Name ‘Mütze oder Haube (?) des Meeres’ … direkt auf die Mu-sir-kišda d. i. Haube (?) (des Himmels) = Anu als Gegensatz hinweist ..." There were two 'caps' (Mütze) in the (ecliptic) sky, one in the north and one in the south, like head coverings for the sky. I suppose these 'caps' were oriented like Ç and È ('cap' and 'cup'). This concept is quite similar to (I believe) what the Easter Islanders thought, as illustrated in tapa mea but also in other glyph types:

As shown in the rightmost glyph the chief (ariki) has a headgear ending in front with two branch points in the now familiar Y-shape (also like that in the glyph at his left). Metoro usually said hau when he saw the middle type of glyph and ha'u = hat. Which all may be summarized in that the tapa mea type of glyph illustrates the two caps of the sky (in A) or the cap of the sky above our heads (in H, P and Q - with a few exceptions where both caps are included in the glyphs). We may now venture to summarize the variants of tapa mea like this:

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||