|

TRANSLATIONS

Back to te pito. If in Saturday there is a kind of rekindling of the light, possibly expressed in the 4 glyphs Hb9-55--58, this would be quite in order structurally seen: it is in the darkest time a new light must be 'born':

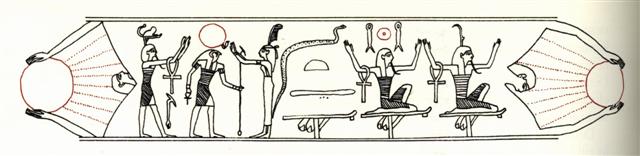

GD24 (pu) in Hb9-55 presumably shows henua outstretched in an east-westerly direction (the path of the sun). The holes through which sun emerges and disappears are visualized at the ends of this henua, like in the Egyptian concept:

By Hb9-56 (rei miro) we are informed about the arrival of a new period, a 'birth'. In Hb9-57 a special kind of henua (possibly qualified by manu rere in Hb9-58) tells us about the result. The form of the henua may have been drawn to allude to Hb9-55. Perhaps it is a new henua p˙, either an immature one yet without holes or the remnant (carcass) of the one in Hb9-55 - the holes are gone because the holes symbolize the double-period (fortnight?) just born. Placenta: henua o te poki. Let us repeat:

*Hb8-16 is the glyph which is parallel to Pb9-33. It is very remarkable that there should be a disappeared glyph exactly here. Nowhere else in the lines b2-b10 is there any damage. It cannot be a coincidence I think. Someone must have destroyed the te pito glyph, not by accident but by knowing its meaning and with a wish to obliterate. Maybe the reason is similar to the disappearance of the great lobster - the symbol must go because what it symbolized is dead and gone. I have above suggested that there is a similarity in form between the glyph types which are exemplified by Hb9-55 and Hb9-57, and that the similarity is due to a common denominator, viz. henua:

I now wish to move into a difficult chapter. The strip of earth which we can imagine in pu perhaps is the same one we can see in the right glyph. The holes are gone, but otherwise there is no difference. (Although that is evidently a lie: the shape in the right glyph is not regular as in the left glyph.) Pb9-33, on the other hand, may illustrate a 'spooky' kind of tree (oriented vertically of course):

We recognize the 'hole' from pu, and I guess it is on its way up into the sky by way of climbing the cosmic tree. The idea can explain also what we see in Ab8-43 and Aa2-9:

Among the henua glyphs in Tahua I can identify 6 worthy of attention in this discussion:

We remember Aa8-32, which we can interpret as the result of the new fire in Aa8-30:

To argue for my new ideas I wish at first to quote from LÚvi-Strauss: "... All the myths just referred to deal with the relationship between sky and earth, whether the theme is cultivated plants resulting from the marriage of a star with a mortal, or cooking fire which disunites the sun and earth, once too close to each other, by coming between them, or man's shortened life-span, which is always in all cases the result of disunion. The conclusion seems to be that the myths conceive of the relationship between sky and the earth in two ways: either in the form of a vertical and spatial conjunction, terminated by the discovery of cooking, which interposes domestic fire between sky and earth; or in the form of a horizontal and temporal conjunction, which is brought to an end by the introduction of the regular alternation between life and death, and between day and night ..." (The Origin of Table Manners) Sun and most other stars (not the circumpolar ones) rise in the east and 'die' in the west. There is only a temporal conjunction between them and us. We look at the horizon in the east and at the horizon in the west - the temporal conjunctions are horizontal. The domestic fire has flames and smoke which rises towards the sky, a vertical movement. Though, also trees are vertical, and - like domestic fires - may be used as a symbol for the raised sky. The canoe moves horizontally, a symbol for how life starts (the beginning of the journey) and ends (arrival). The canoe is a symbol of life. The trees do not move, yet they live. When they have died they are allowed to be used as fuel in the domestic fires (or as boards in a canoe). Dead trees are symbolized by Y. "... There is an Amazonian story ... to the effect that the sun and the moon were once engaged, but marriage between them came to seem impossible: the sun's love would set fire to the earth, the moon's tears would flood it. So they resigned themselves to living separately. By being too close to each other, the sun and the moon would create a rotten or a burnt world, or both these effects together; by being too far apart, they would endanger the regular alternation of day and night and thus bring about either the long night, a world in which everything would be inverted, or the long day, which would lead to chaos. The canoe solves this dilemma: the sun and moon embark together, but the complementary functions allocated to the two passengers, one paddling in the front of the boat and the other steering in the back, force them to choose between the bow and the stern, and to remain separate. This being so, ought we not to recognize that the canoe, which unites the moon and the sun and night and day, while maintaining a reasonable distance between them during the time of the longest journey, plays a similar part to that of domestic fire in the space circumscribed by the family hut? If cooking fire did not achieve mediation between the sun and the earth by uniting them, the rotten world and the long night would prevail; and if it did not ensure their separation by coming between them, there would be a conflagration resulting in the burnt world. The canoe fulfils exactly the same function in the myths, but transposes it from the vertical to the horizontal, from distance to duration ..." (The Origin of Table Manners) We should endorse these ideas, because at new year the thoughts of the rongorongo men centered around not only stamping out the old fire in order to ignite a new one but also on how the new life must be brought onboard the celestial canoe to protect it from the water:

The canoe is for travelling horizontally across the water, yet rei miro glyphs are standing vertically on their front ends:

I wrote in my glyph dictionary: 'Possibly the vertical orientation is partly due to a wish to save horizontal space for the glyphs in the lines of the rongorongo board. Wood was scarce on Easter Island and thoughts of economy may have influenced ...' Later I have come to the conclusion that the reason for the vertical orientation perhaps is that at the cardinal points (the only justifiable locations of GD13 glyphs) the canoe has to turn, change direction. Is not the vertical orientation then a sign of changing direction? At the solstices the sun's direction is horizontal, yet it does not move. A new fire must be ignited to make it move. Now we are prepared to read what I have intended to arrive at for a long time now. I cite from The Origin of Table Manners: "... Among the Arapaho and in several other communities too, this myth, [of] which I have quoted a number of variants, is one of the foundation myths connected with the most important annual ceremony of the Plains Indians and their neighbours. This ceremony, generally referred to as the 'Sun Dance', probably because its Dakota name means 'to stare at the sun', followed a different pattern according to the group. Nevertheless, it had a syncretic aspect, which can be explained by imitations and borrowings. In times of peace, invitations were sent out far and wide and visitors were impressed by certain rites, which they remembered and mentioned later. The number of episodes and the order in which they followed each other were not the same in all cases, but in broad outline the form of the sun-dance can be described as follows. I think about the evident differences among the rongorongo texts: the number and order in which certain key glyph sequences appear may be due to a similar process - different writers borrowing yet creating their own products. It was the only ceremony performed by the Plains Indians in which the entire tribe took part; other ceremonies involved only particular brotherhoods of priests and certain age-grade societies. Te Piringa Aniva, I think. ... The cult place of Vinapu is located between the fifth and sixth segment of the dream voyage of Hau Maka. These segments, named 'Te Kioe Uri' (inland from Vinapu) and 'Te Piringa Aniva' (near Hanga Pau Kura) flank Vinapu from both the west and the east. The decoded meaning of the names 'the dark rat' (i.e., the island king as the recipient of gifts) and 'the gathering place of the island population' ... After remaining scattered during the cold season in small groups established in sheltered spots, the Indians came together in the spring for the collective hunt. At the same time as the tribe recovered its full complement of members, abundance replaced scarcity. From the sociological, as well as the economic, point of view, the beginning of summer gave the whole group the opportunity to live together again as an entity, and to celebrate its new-found unity with a great religious feast ... An observer who saw the sun-dance in the second half of the 19th century notes: 'the requirement of the Sun Dance is such that it requires every member of the tribe to be present: every clan must be present and in their place' ... At winter solstice there certainly must have been a ta'urua (Great Festivity) on Easter Island, the only time when both the Ariki and the whole population was present while the rongorongo texts where recited.

... So, in principle, the ceremony took place in summer. However, instances are on record when it was celebrated later in the year. The sun-dance was linked not only to the main seasonal cycles which regulated the collective life of the tribe, but also to certain incidents in the life of the individual. A member of the tribe would make a vow to celebrate the feast the following year in recognition of his escape from some danger, or because he had recovered from an illness. Preparations had to be made a long time in advance; the complicated sequence of rites had to be organized, provisions had to be collected for the feeding of the guests and gifts collected to be given to the officiants in repayment of their services. Also, the new 'owner' of the dance had to receive his title from his predecessor, and, from the priests and other qualified dignitaries, the rights attaching to the various phases of the ritual. During these transactions, he solemnly handed over his wife to the man he called his ceremonial 'grandfather', and whose 'grandson' he became, for the purposes of a real or symbolic act of copulation, which took place out of doors at night in the moonlight, and during which the grandfather transferred a piece of root, representing his semen, from his own mouth to that of the wife, who then spat it into her husband's mouth. The kava ceremony, I think. Furthermore 'grandfather' and 'grandson, with the 'wife' being impregnated certainly must have to do with the two 'suns'.

Throughout the feast which lasted several days the officiants fasted and neither ate nor drank - the Plains Cree called the ceremony 'the-abstaining-from-water-dance' ... - and submitted to various mortifications. For instance, the penitents ran sharp wooden skewers into their dorsal muscles, and made them fast to thongs attatched to the central pole, around which they danced and leapt until the skewers were wrenched out, together with the flesh; or else they trailed behind them heavy objects, such as buffalo skulls with horns which dug into the ground. These objects were attatched to their backs in the same way, and with the same result. At their backs (tu'a) the dead (buffalo in this instance) skull with 'horns' digging into the ground, I think, symbolizes the impregnation of mother earth by the 'grandfather'. Or the digging stick used by Kuukuu:

First, the priests and chief officiants met in a tent set up apart from the others, in order to proceed in secret with the preparation or renewal of the liturgical objects. Then, groups of warriors went to fetch the tree-trunks necessary for the erection of the framework of a huge lodge roofed over with branches. The trunk intended to serve as the central pole was hacked at and felled as if it were an enemy. It was in this public lodge that the rites, songs and dances took place. In the case of the Arapaho and the Oglala Dakota, at least, it would seem that a period of unbridled licence prevailed, and was perhaps even prescribed, on this night ... While the generic name given to this group of extremely complex ceremonies probably exaggerates their solar inspiration, the solar element should not be underestimated. In actual fact, sun-worship was ambigous and equivocal in character. On the one hand, the Indians prayed to the sun to be favourably disposed towards them, to grant long life to their children and to increase the buffalo herds. On the other hand, they provoked and defied it. One of the final rites consisted in a frenzied dance which was prolonged until after dark, in spite of the exhausted state of the participants. The Arapaho called it 'gambling against the sun', and the Gros-Ventre 'the dance against the sun'. The aim was to counteract the opposition of the intense heat of the sun, who had tried to prevent the ceremony taking place by radiating his warm rays every day during the period preceding the dance ... The element of hazard at a cardinal point obviously is not a consequence of the threat of heat. Turning the 'canoe' always involves a risk. At the dark chaotic times when no star guides the course anything might happen. We remember how Thoth won 5 black nights from the moon in order to enable births and how the old Babylonians' saw a hall of hazard (Schicksalskammer) at the end of each 'year'.

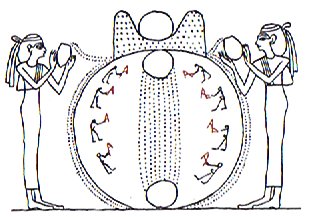

The Indians, then, looked upon the sun as a dual being: indispensable for human life, yet at the same time representing a threat to mankind by its heat, a presage of prolonged drought. One of the motifs of the Arapaho dancers' body-paintings shows them being 'consumed by fire' ... An informant belonging to the same tribe relates that 'in the past, during one sun-dance, it became so hot that the pledger (officiant) was unable to continue the ceremony and left the lodge. The other dancers followed, as they could not continue the dance without him' ... But the sun was not alone in being involved: the Thunder-Bird's nest was placed in the fork of the central pole. The link with thunder, and more especially with spring storms, emerges even more clearly in the mythology of the central Algonquin, according to whom the dance, referred to elsewhere as 'the sun-dance', had replaced an ancient ritual intended to hasten the arrival of the rain-storms ... In the Plains, too, the dance fulfilled a dual purpose, which was to conquer an enemy, usually the sun, and to force the Thunder-Bird to release rain. One of the foundation myths concerning the dance describes a great famine which an Indian and his wife succeeded in bringing to an end by their knowledge of the rites and the recovery of fertility ... There is, then, a very close analogy between the sun-dance, as performed by the Plains Indians, and the ceremony of the great fast, as celebrated by the SerentÚ Indians to ensure that the sun continued exactly on its course, and brought the drought to an end ... In both cases, the ceremony concerned was the major one of the tribe and involved all its adult members. The officiants neither ate nor drank for several days. The ritual was performed near a pole which represented the path to the sky. Around this pole, the Plains Indians danced and whistled in imitation of the Thunder-Bird's cry. To whistle is dangerous at sea (I remember from somewhere) a storm might come. The SerentÚ did not erect their pole until they had heard the 'whistling', arrow-bearing wasps ... Wasps characterize the hot summer season, as we have seen in this Egyptian picture:

In both instances, the ritual ended with the distribution of consecrated water. In the case of the SerentÚ, the water was contained in separate receptacles and could be pure or roiled (meaning 'turbid' or 'tainted'); the penitents drank the pure water but refused the other. The 'perfumed water' used in the Arapaho rite was sweet, yet it symbolized menstrual blood, a liquid not in keeping with the sacred mysteries ..." My purpose in citing this long piece is manyfold. First of all we need to get a picture of how an Easter Island ancient new year ceremonial feast gathering all the people (Te Piriga Aniva) might have 'transpired'. Then, the sun-dance affirms a lot of the ideas earlier tentatively suggested, about how the ancient world view looked. The path to the sky is a tree, for example. Though the path of the sun canoe is horizontal. The tree fork is the American (probably also Easter Island) equivalent of the T into which shape the oak was hacked at midsummer:

Once again LÚvy-Strauss: "... the officiant in the SerentÚ rite climbs to the top of the pole until he obtains fire from the sun to rekindle the flames of the domestic hearths, and a promise to send rain, that is, two forms of moderate communication between the sky and the earth, which the sun's hostility towards men threatened to conjoin with a consequent conflagration. ... One of the main rites of the dance consists in the offering of a human wife to the moon. The central pole in the ceremonial bower represents the tree climbed by the heroine in the myth [about a 'porcupine' lodged in the Tree], and belongs to the same species (Populus sp.). A bundle of branches, with a digging-stick inserted in it, is set in the fork left at the top of the trunk after all the other limbs have been lopped off. This tool is said to be the one used by the moon's human wife to remove the root blocking the celestial vault, and which she laid across the opening so at to attatch to it the end of her rope made of sinew ..." The kava ceremonies were in a way similar (and this is another reason why I have used so much time-space for the sun-dance):

I cannot resist the temptation to put forward the idea that Aa2-46 may have something to do with the kava ceremony:

The two 'balls' generated from the remains of an old henua pu could be 'white cowries', buli leka. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||