|

TRANSLATIONS

The black slug which secretes a sticky fluid (piripiri) has three fundamental characteristics: It is slow, it is black and it is sticky. From this follows that hakapipiri becomes to 'glue'. To 'catch' is pipiri, a similar concept. We remember how the sun moves slow at solstice, as if he was a slug or as if caught in a snare:

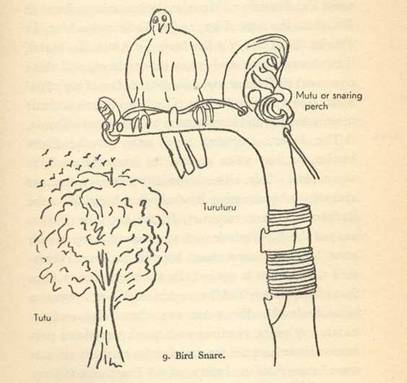

... The 'snaring perch' is called mutu, the tree tutu and turuturu perhaps indicates the bird. It can hardly be a coincidence, I thought, that of the 8 vocals all of them should be u. Mutu we have met before, that is the name of one of the nights in the moon calendar ... There is no observed slowing down at new moon, similar to how the sun behaves, therefore piriga cannot be the correct word. Moon just comes to her end (mutu):

Possibly mutu is a word suitable for the end of the week, too. Is that an explanation for the right legs cut short (Hawaiian: He kanaka wāwae muku) in Saturday:

(In Pb10-56 the right 'eye' is nearly black.) The measure mutu, which I guess means ¾, gives as a unit the stretch from the tips of the fingers of one hand (probably the left) to the fingertips of the other (right). Hakapiri is to join together, in other words what glue is used for. Joining together is also aggregation or uniting, which explains piriga in Te Piriga A Niva, the place where people assemble, unite, at the black time. Te Piriga A Niva is on one side of Vinapu and Te Kioe Uri (The Black Rat) on the other side. Vinapu must be the center of darkness. In Barthel 2 we read: ... Thus, the last month of the Easter Island year is twice mentioned with Vinapu. Also, June is the month of the summer [a misprint for winter] solstice, which again points to the possibility that the Vinapu complex was used for astronomical purposes ... The misprint is interesting. June is at winter solstice, not at summer solstice. Vinapu is the center for determining when the new year begins. Therefore it is in a way more important than Anakena at the other end of the island (year). At midsummer the solar king is at his strongest. At midwinter he is weak. From this we may conclude that Aa5-50 is at Vinapu:

The expression a neva (lethargic) implies weakness. However, this interpretation cannot be right, because in line a5 we are in summer, not in winter. Furthermore, a standing figure - if solar in character - means that sun is standing high. Therefore Aa5-50 is not at Vinapu but at Anakena. Earlier, discussing noon and the standing person in Aa1-24, we concluded that maybe he (sun at noon) was located at Poike; equinox time would be a good compromise between the extreme points. It is not certain that every standing person is located at summer. The black single eye, together with the 4 feathers distributed more to the left than to the right implies we should think about the 1st half of the year, Haua. What did Metoro mean with mai hiti rua a neva?

One possibility is to translate mai hiti rua as 'from the eastern pit' (whence sun rises). Given the yearly path of the sun that could mean the early part of the year, i.e. Haua. Though rua has the curious other meaning too: '2'. Is there an allusion in rua where a pit (at the horizon) always must have 2 inhabitants, one arriving in the east when the other is going down in the west. The Janus concept (takurua) implies that there must be 2 'persons'. Number 2 is 'going down' at new year, when number 1 is arriving. Haua is number 1 and Makemake is number 2. "... While the priests tried to make the deities favorable toward those who resorted to them (hatu o te manu kia Haua, kia kia Makemake), the young people were busy making earth ovens ..." (Métraux) One 'kia' for Haua, two ('kia kia') for Makemake. The wished for good omens at new year, the hope for a 'flood of goods', was by sympathetic magic illustrated for the gods by all the people swarming and milling around (kau as in Rano Kau). "A faint memory has been preserved of ceremonies performed to invoke rain from the god Hiro. When a drought threatened crops the people resorted to various magic rites and to the ariki-paka (noble priests?) who addressed prayers to the god. According to Routledge... the people anxious to obtain rain first asked the king for help. The king then sent to the scorched fields a younger son and another ariki-paka. No reference to this special choice was made by my modern informants, but Estella ... was also told that the king acted as an intermediary between the people and the priests. The ariki-paka who presided over the ceremony were painted 'on one side red, on the other black with a strip down the center' ... They went to the hop of a hill, taking seaweed (miri-tonu) and pieces of drift coral (karakama). The magical significance of this offering of things soaked wioth sea water is obvious ..." (Métraux) From seawater to the wished for fresh water there is a short step (past the 'strip'): "The ceremonies and feasts connected with the bird cult were performed at Orongo, on the slopes of Rano-kau at the southwest point of the island. The village of Orongo lies on the narrow ridge separating the sea from the crater lake. It was temporarily occupied at the time of the yearly feast and deserted the rest of the year." (Métraux) Although the bird-man season arrived in spring (and not at new year) 'one side red and the other black' surely refers to the scheme of summer (red) contra winter (black) and the parallel 'fresh water' contra 'seawater'. Once again we arrive at the dilemma: Should we regard the year as divided in two according to the solstices or according to the equinoxes? According to Tahua it looks as if spring equinox may be the crucial point:

Should we understand the first running 'commander' (ragi) to represent winter and the second summer? That would explain the signs in the parallel glyphs:

In Ha5-28 the ragi sign has lost one of the 'horns' of the moon - indicating lesser power for the moon. In Pa5-9 the 'running leg' is without toes (no fiery light) and it has an open end ('spooky', night character). In Qa5-17 there is a little rhomb below the 'running leg', possibly indicating the opposite to the round character of the sun. The ordinal numbers (4, 28, 10 and 18) all are even and express natural limits of a season cycle. |