|

TRANSLATIONS

"There was a woman watching over a skull on a rock in the bay of Tonga-riki, in front of the ahu Tonga-riki. The spirit Puna of the ahu was always looking at the priestess. One day a wave came and took the skull that was watched on the rock in front of the bay of Tonga-riki. The wave swept away the skull from above; it floated. The eyes of the priestess saw the skull. She leaped to take it, she swam behind the skull which floated ahead. She arrived in the middle of the sea, she was tired, she landed on the island of Matiro-hiva. Haua saw this woman who was a priestess. He asked: 'Where do you come from?' 'I am pursuing my skull.' Haua said: 'It is not a skull, but the god Makemake.' ... (Métraux) Haua is a name which I connect in my mind with hau. In the list over the GD19 (hau) glyphs we note that Metoro used the word haua in a few places (though only in the Tahua text):

Searching in my Polynesian dictionary I cannot find any example of hahaua, but motuhaua means 'archipelago'. The island of Matiro-hiva probably is identical with Motu Motiro-hiva:

The suffix -hiva implies 'not belonging to Easter Island'. We recognize the structure of the story, the female swimming and reaching a new land: ... There is a couple residing in one place named Kui and Fakataka. After the couple stay together for a while Fakataka is pregnant. So they go away because they wish to go to another place - they go. The canoe goes and goes, the wind roars, the sea churns, the canoe sinks. Kui expires while Fakataka swims. Fakataka swims and swims, reaching another land. She goes there and stays on the upraised reef in the freshwater pools on the reef, and there delivers her child, a boy child. She gives him the name Taetagaloa. When the baby is born a golden plover flies over and alights upon the reef. (Kua fanau lā te pepe kae lele mai te tuli oi tū mai i te papa). And so the woman thus names various parts of the child beginning with the name 'the plover' (tuli): neck (tuliulu), elbow (tulilima), knee (tulivae). They go inland at the land. The child nursed and tended grows up, is able to go and play. Each day he now goes off a bit further away, moving some distance away from the house, and then returns to their house. So it goes on and the child is fully grown and goes to play far away from the place where they live. He goes over to where some work is being done by a father and son. Likāvaka is the name of the father - a canoe-builder, while his son is Kiukava. Taetagaloa goes right over there and steps forward to the stern of the canoe saying - his words are these: 'The canoe is crooked.' (kalo ki ama) Instantly Likāvaka is enraged at the words of the child. Likāvaka says: 'Who the hell are you to come and tell me that the canoe is crooked?' Taetagaloa replies: 'Come and stand over here and see that the canoe is crooked.' Likāvaka goes over and stands right at the place Taetagaloa told him to at the stern of the canoe. Looking forward, Taetagaloa is right, the canoe is crooked. He slices through all the lashings of the canoe to straighten the timbers. He realigns the timbers. First he must again position the supports, then place the timbers correctly in them, but Kuikava the son of Likāvaka goes over and stands upon one support. His father Likāvaka rushes right over and strikes his son Kuikava with his adze. Thus Kuikava dies. Taetagaloa goes over at once and brings the son of Likāvaka, Kuikava, back to life. Then he again aligns the supports correctly and helps Likāvaka in building the canoe. Working working it is finished ... The 'crooked canoe' is another 'house' in need of rebuilding. A skull is formed like an egg and represents the generative power in the watery darkness, the po-tency. In English Etymology it becomes very clear: "potent1 ... powerful ... L potent-, potēns, prp. of *potēre, posse be powerful or able ... the base *pot- is repr.also by Skr. pátis lord, possessor, husband, Gr. pósis spouse ..." "potent2 ... (her., of a cross) having the limbs terminating in crutch-heads ..." The 'crutch' is the 'crotch', our everywhere appearing Y, the receiving end. In the 'middle of the sea' must mean the winter solstice, when the new fire is alighted. Sala-y-Gómez lies east of Easter Island and is therefore a suitable place for a new birth. Furthermore, around the island the fishing is good and birds swarm around it. Motu Motiro Hiva is the best symbol for the fruitfulness of mother nature.

"The economic value of the numerous sea birds is based on their eggs and on the use of their feathers. During the sping months, bird eggs (mamari) were a welcome addition to the menu. In November 1957, I observed men and boys going out to the steep rock of Marotiri, the last extensive nesting ground for the sea birds, and returning with hundreds of bird eggs, which were immediately distributed in the village and consumed.

While there were no longer rules limiting the number of eggs taken, such regulations must have existed in the old culture, at least in the Motu Nui area. According to the mythology, the sea birds came from Motu Matiro Hiva (i.e., Sala-y-Gomez), stirred up by the gods Makemake and Haua (Knoche 1925:259-260; ME:312-313; Felbermayer 1971:111-113). Attempts by the birds to nest at various points along the southern shore never succeeded because time and again the people took away their eggs. The first protected place is Motu Nui, the 'place without people, where it is good for the birds' (kona tangata kore oira i rivariva i te manu) ..." (Barthel 2) I imagine that Haua and Makemake possibly are described with Aa4-58 and Aa4-60:

My interpretation is based first of all on the similarity between the words Haua and hau (GD19). Secondly, I have classified these unusual glyphs as belonging to GD19, due to the top part which is rounded and have 'feather' signs on them. Thirdly, although Metoro did not say hau here, he expressed his opinion of the meaning by saying: ki te ragi resp. e pare tuu ki te ragi. I think he was talking about the 'commanders' (ragi), i.e. the gods in the sky. 4thly, my earlier ideas about these two glyphs (obviously belonging together, yet mirror images), do not contradict the new ideas: ... Aa4-58 and Aa4-60 are very strange glyphs without - as far as I have been able to ascertain - parallels anywhere among the rongorongo texts. But we can observe the 'knee' at left in Aa4-58 and at right in Aa4-60 - probably indicating the shift from waxing to waning phase. One (black?) 'eye' in the 'head' of Aa4-58 is changed into two (one black and one white?) in the (double?) head of Aa4-60, as if the 'fire' of the old half-year has gone and a new 'fire' been alighted from the old. Aa4-58 has 'spooky arms' presumably indicating 'ghost' status. To be more specific: the left ('spooky' or 'female' figure) is Haua, while the right is Makemake. I identify them with the 2 halves of the cycle. In Hawaii, at new year, we have Haumea briefly mentioned: ... The 'living god', moreover, passes the night prior to the dismemberment of Lono in a temporary house called 'the net house of Kahoali'i', set up before the temple structure where the image sleeps. In the myth pertinent to these rites, the trickster hero - whose father has the same name (Kuuka'ohi'alaki) as the Kuu-image of the temple - uses a certain 'net of Maoloha' to encircle a house, entrapping the goddess Haumea; whereas, Haumea (or Papa) is also a version of La'ila'i, the archetypal fertile woman, and the net used to entangle her had belonged to one Makali'i, 'Pleiades' ... 5thly, I identify Haua with the Hawaiian Haumea, the 'archetypal fertile woman'. The appendix -mea means red (the colour of growth and abundant life):

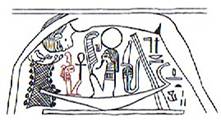

I have earlier written about Haumea: ... when I once again reread the cited passage, I for the first time notice that we have here a goddess Haumea, which sounds like a combination of hau tea and tapa mea. The night side of Haumea could be hau (tea) and the day side could be (tapa) mea. Together these two glyph types would then represent Mother Earth. Haumea is Mother Earth (Papa), but she is also La'ila'i, i.e. Ragiragi, 'sky-sky' (?). Earth and sky are close. Here both are women. In old Egypt the sky was Nut, also a woman. A few hours after having written this I discovered that in Churchill 2 there was a description of the meaning of the word la'ila'i: '[Efaté:] langilangi, to be proud, uplifted. Samoa: fa'alangilangi, to be angry because of disrespect. Tonga: langilangi, powerful, great, applied to chiefs; fakalangilangi, to honour, to dignify, to treat with great respect. Hawaii: lanilani, to be proud, to show haughtiness. Uvea: fakalai, to compliment, to adulate. Viti: langilangi, proud.' Clearly there is here a net behind the back of the goddess Maat (picture from Wilkinson):

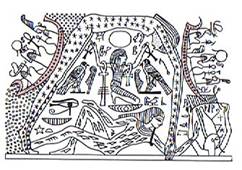

In another picture (from Wilkinson), where focus is on the ships of the sun travelling over the sky, we also can see this net:

The net was important in the Hawaiian new year ceremonies: ... Just so, the succeeding Makahiki ceremony, following upon the putting away of the god, is called 'the net of Maoloha', and represents the gains in fertility accruing to the people from the victory over Lono. A large, loose-mesh net, filled with all kinds of food, is shaken at a priest's command. Fallen to earth, and to man's lot, the food is the augury of the coming year. The fertility of nature thus taken by humanity, a tribute-canoe of offerings to Lono is set adrift for Kahiki, homeland of the gods .... The creators of the ceremony gave hope to the people that the coming year would be abundant (with new life). 6thly, we have the kuhane of Haumaka. The combination of hau and maka probably is meant to allude to Haua and Makemake. "No mention has ever been made of Haua except in connection with Makemake. The formula which accompanies an offering to Makemake always includes Haua who appears in the myth as the god's companion." (Métraux) Make and maka are different, but: "The first allusion to Makemake is found in the early account of Gonzalez expedition ...: I observed that on the day on which we erected the crosses, when our chaplain went accompanying the litanies, numbers of natives stepped forward onto the path and offered their cloaks, while the women presented hens and pullets, and all cried Maca Maca, treating them with much veneration until hey had passed beyond the rocks by which the track they were following was enbumbered ..." (Métraux) |