|

TRANSLATIONS

If we now continue by comparing the designs of the

glyphs in the first internal parallel, it becomes fairly obvious that

those on side a are 'sunny', but

not those on side b:

|

b |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Ab1-14 |

Ab1-15 |

Ab1-16 |

Ab1-17 |

Ab1-18 |

Ab1-19 |

Ab1-20 |

|

a |

|

|

|

|

- |

|

|

|

Aa4-13 |

Aa4-14 |

Aa4-15 |

Aa4-16 |

Aa4-17 |

Aa4-18 |

Aa4-13 has a bottom

with flames. 4 * 13 = 52 = the number of weeks in a

year and honu (GD17) may signify winter solstice time.

The 'beak' at right is 'open', which could mean abruptly

discontinued (because the year is 'finished'). I remember having

written about such 'beaks' when trying to decide how to define

which glyphs should belong to GD11 in the glyph catalogue:

| There is a problem when a

GD11 type of beak exists on a totally different

type of glyph, e.g. Ab4-65 (GD17):

Cfr the left - from us seen -

top 'flipper'. Such an easily missed sign is not

reason enough to sort a glyph under GD11. |

Already the 'beak'

as such presumably indicates the carrion bird which will take

care of the carcass (of the old period, now 'finished').

Therefore Aa4-13 in a way seems to talk about the 'going away'

of the now well fed dark bird. We should remember Rb1-105 and

one of the earlier discussions around this subject:

... To extinguish a fire is to kill it. Fire is a strange

element not like anything else ... it is moving, it is eating

and it is even making noices, 'talking'. It is alive. To make a

fire is to make life. To extinguish a fire is to kill. Therefore

the pruning-knife, possible to use not only to reap but also for

other executions, is an adequate symbol for extinguishing fire.

... That Cronos the

emasculator was deposed by his son Zeus is an economical

statement: the Achaean herdsmen who on their arrival in Northern

Greece had identified their Sky-god with the local oak-hero

gained ascendancy over the Pelasgian agriculturalists. But there

was a compromise between the two cults. Dionë, or Diana, of the

woodland was identified with Danaë of the barley; and that an

inconvenient golden sickle, not a bill-hook of flint or

obsidian, was later used by the Gallic Druids for lopping the

mistletoe, proves that the oak-ritual had been combined with

that of the barley-king whom the Goddess Danaë, or Alphito, or

Demeter, or Ceres, reaped with her moon-shaped sickle. Reaping

meant castration; similarly, the Galla warriors of Abyssinia

carry a miniature sickle into battle for castrating their

enemies ...

... Without any special effort whatsoever my work with trying to

understand the rongorongo texts is flowing on

synchronously. Parallel with writing here I am documenting the

text of Small Wasington (R) and by coincidence the R-text to a

large extent happens to be parallel with the A-text (Tahua).

While thinking about the great carrion bird I suddenly saw a

complex glyph (Rb1-105) which possibly describes the 'pruning':

Aside from the

visual impact there is a kind of affirmation in a parallel text

(in triplicate) in Q (but not in H and P), which may tell about

3 'pruning times' during the year:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Metoro

used to say hoea at GD43, an instrument for

tattooing. |

Somewhat later I

added: ... I would now like to return to Rb1-105

which I imagine is showing us 'Saturn' (in bird reincarnation)

cutting up the time into two pieces: past (henua at left)

and future (henua at right).

His attachment to

the past is seen in his left (from us seen) foot being attached

to the henua at left. His 'fists' probably depict the

past year (left) and the new year (right) and he is sitting in

the middle, i.e. in the X-area. The new year is holding the

'knife'.

Metoro,

I happened to notice, probably saw another such 'knife' (i.e.

formed like the beak of a carrion bird) in the left (from us

seen) 'wing' of this 'turtle' (Ab4-65)

because he said ko motumotu (and motumotu means

'to cut up', according to Churchill) ...

... Maybe the

marks on the head of the bird indicates 'fire' (symbolized by

feathers) to tell us that we see the Phoenix in action. The

trees may then be coconut palms (niu) and we may think of

his cutting with 'beak-knife' as making notches ...

The sun flames at bottom of Aa4-13

tells about the new fire, and possibly the bottom part of Aa4-14 is

a picture of the 'grill' just having been realighted. The

'grill' may be the former 'broken canoe', now a spirit as

indicated by the two open limbs. Sugar canes (tôa) are

broken (they are stiff as warriors, tóa):

"There was a young

man living in Riu-o-hatu. He planned to make a feast (koro)

for his father. For that purpose he raised chickens and had a

house built. All his people worked on it. When his koro

house was finished, he left his people and went to Ahu-te-peu

to call on Tuu-ko-ihu and ask him for a statue. He

arrived at Tuu-ko-ihu's place and asked: 'Give me a

statue, o king, in loan for the feast in honor of my father.'

The ariki

said: 'It is all right.' Tuu-ko-ihu gave him an image.

The young man took it and returned to his koro. He broke

sugar-cane stalks, dug out yams and sweet potatoes and put

bananas in a ditch. He lit the oven and put in it fowls, yams,

and sweet potatoes. Some people sang

riu chants, others, ei chants and others a te atua.

|

Rîu Song which may be good and decent (rîu rivariva),

or bad and indecent (rîu rakerake); the term rîu is often

used for serious, sad songs: rîu tagi mo te matu'a ana mate, sad

song for the death of a father. Vanaga.

Sa.: liu, liliu, to turn, to go backward

and forward. To.: liu, liuliu, to return. Fu.: liliu,

to return, to go over or come back. Niuē:

liu, liliu,

to turn, change, return. Uvea: liliu,

to turn, to return. Ma.: ririu,

to pass by. Ta.: riuriu, to

go around in a circle. Mgv.: akariu,

to come and go. Vi.: lia, to

transform, to metamorphose. Churchill 2. |

| Êi

Lampoon, song composed to ridicule or to defame. Vanaga. |

| A, á A.

1. Prep.: for, over, by; a nei, over here; a ruga, above;

a te tapa, by the side. 2. Genitive particle, used preceding

proper names and singular personal pronouns: te poki a Mateo,

Mateo's child; aana te kai, the food is his. 3. Particle often

used before nouns and pronouns, especially when these are introduced by

a preposition such as i, ki; ki a îa, to him, for him. Vanaga.

Á. 1. Á or also just a,

article often used preceding proper names and used in the meaning of

'son of...': Hei á Paega, Hei, son of Paenga. 2. Very common

abbreviation of the particle ana, used following verbs:

ku-oti-á = ku-oti-ana; peira-á = peira-ana. 3. (Also

á-á.) Exclamation expressing surprise or joy, which can also be

used as a verb: he-aha-koe, e-á-ana? what's happening with you,

that you should exclaim 'ah'? He tu'u au e-tahi raá ki te hare o Eva

i Puapae. I-ûi-mai-era ki a au, he-á-á-mai, he-tagi-mai 'ka-ohomai, e

repa ê'. one day I came to Eva's house in Puapae. Upon seeing me she

exclaimed: 'ah,ah' and she said, crying: 'Welcome, lad'. Vanaga. |

| Atua, atu'a 1. Lord, God: te Atua ko Makemake, lord Makemake. Ki a au

te Atua o agapó, I had a dream of good omen last night (lit. to me

the Lord last night). 2. Gentleman, respectable person; atua Hiva,

foreigner. 3. Atua hiko-rega, (old) go-between, person who

asks for a girl on another's behalf. 4. Atua hiko-kura, (old)

person who chooses the best when entrusted with finding or fetching

something. 5. Atua tapa, orientation point for fishermen, which

is not in front of the boat, but on the side.

Atu'a,

behind. Vanaga. God, devil. Churchill. |

They took all the

foods - bananas, sugar cane, fowls - to the koro house.

They set up the image at the door of the koro house, and

the people went to admire this image. They spent three days in

the koro house. This koro house was nice, and the people

ate plenty of sugar cane and bananas.

I suspect that sugar

canes are male in character (straight and stiff), while bananas

are female (soft and bent).

(picture from Wikipedia)

When the koro

was finished, the young man stayed there. The third day, the

koro caught fire. Men, women, and children shouted: 'The

koro is burning, the koro is burning.'

This cry sounded at

Hanga-roa, at Motu-tautara, at Ahu-te-peu.

Tuu-ko-ihu heard it and said: 'O my brother 'The

jumping-little-bird' (piu-hekerere) jump!'

A servant of

Tuu-ko-ihu was sent to Riu-o-hatu. When the young man

saw him, he said: 'Your image is burnt up.'

The servant said:

'No, it did not burn.' He looked for it and found it lying far

away. The servant called the owner of the koro and said. 'Here

is your image.' He returned it to Tuu-ko-ihu." (Métraux)

This simple little story contains

important clues. First we observe 3 + 3 = 6 days, the first 3

days when the feast is ongoing and the latter 3 days afterwards,

when the young man (curiously without being given a name) lives alone

in the koro house.

6 means the sun, very clearly so

when we see the division into two groups of three

(double-months). However, 6 may also refer to those extra 6 days

needed at leap year (366 - 360). The jumping-little-bird then

should be the new year born beyond the regular 360 days. He must

jump across the gap between 366 and 1.

The father is obviously dead and we

guess he is the old year. A feast (koro) commemorating

him is the fundament of the story.

| Koro

1. Father (seems to be an older word

than matu'a tamâroa). 2. Feast, festival;

this is the generic term for feasts featuring songs

and banquetting; koro hakaopo, feast where

men and women danced. 3. When (also: ana koro);

ana koro oho au ki Anakena, when I go to

Anakena; in case, koro haga e îa,

in case he wants it. Vanaga.

If. Korokoro, To clack the

tongue (kurukuru). Churchill.

Ma.: aokoro, pukoro,

a halo around the moon. Vi.: virikoro, a

circle around the moon. There is a complete accord

from Efaté through Viti to Polynesia in the main use

of this stem and in the particular use which is set

to itself apart. In Efaté koro answers

equally well for fence and for halo. In the marked

advance which characterizes social life in Viti and

among the Maori the need has been felt of qualifying

koro in some distinctive manner when its

reference is celestial. In Viti virimbai has

the meaning of putting up a fence (mbai

fence); viri does not appear indipendently in

this use, but it is undoubtedly homogenetic with

Samoan vili, which has a basic meaning of

going around; virikoro then signifies the

ring-fence-that-goes-around, sc. the moon. In the

Maori, aokoro is the cloud-fence. Churchill

2. |

In Churchill 2 we find most

interesting evidence. Koro is not just any feast, but may

originally be the death-of-the-old-year feast. The circle is

closed, and I cannot but feel that basically this feast is a

replica of an older new moon feast, i.e. that Whiro and

viri mean the same thing:

... According to

Makemson some of the names of Mercury are the following:

|

Hawaiian Islands |

Society Islands |

Tuamotus |

New Zealand |

Pukapuka |

|

Ukali

or Ukali-alii 'Following-the-chief' (i.e. the

Sun)

Kawela

'Radiant' |

Ta'ero

or Ta'ero-arii 'Royal-inebriate' (referring

to the eccentric and undignified behavior of the

planet as it zigzags from one side of the Sun to the

other) |

Fatu-ngarue

'Weave-to-and-fro'

Fatu-nga-rue

'Lord of the Earthquake' |

Whiro

'Steals-off-and-hides'; also the universal name for

the 'dark of the Moon' or the first day of the lunar

month; also the deity of sneak thieves and rascals. |

Te Mata-pili-loa-ki-te-la

'Star-very-close-to-the-Sun' |

... As to the

meaning of vi (in Tavi) I suggest that it is

alluding to viri:

|

Viri

1.

To wind, to coil, to roll up; he viri i te hau,

to wind, coil a string (to fasten something). 2.

To fall from a height, rolling over, to hurl down,

to fling down. Viriviri, round, spherical

(said of small objects). Viviri te henua,

to feel dizzy (also: mimiro te henua).

Taviri, to turn around. Vanaga.

To

turn in a circle, to clew up, to groom, to twist, to

dive from a height, to roll (kaviri).

Hakaviri, crank, to groom, to turn a wheel, to

revolve, to screw, to beat down; kahu hakaviri,

shroud. Viriga, rolling, danger. Viriviri,

ball, round, oval, bridge, roll, summit, shroud, to

twist, to wheel round, to wallow. Hakaviriviri,

to roll, to round; rima hakaviriviri, stroke

of the flat, fisticuff. Viritopa, danger.

Churchill.

Viti: vili, to pick up fallen fruit or leaves

... In Viti virimbai has the meaning of

putting up a fence (mbai fence); viri

does not appear independently in this use, but it is

undoubtedly homogenetic with Samoan vili,

which has a basic meaning of going around;

virikoro then signifies the

ring-fence-that-goes-about, sc. the moon. In the

Maori, aokoro is the cloud-fence ...

Churchill 2. |

The sense of

coiling up is a very precise appellation of what goes on in the

X-area:

... In

rongorongo rays of sunlight are visualized with three

vertical straight lines (GD41). Such rays are used as 'poles'

marking limits in time/space (GD37). At the time of new year,

e.g., there will be two such 'poles', one marking the end of the

old year and another marking the beginning of the new year (Takurua).

This structure is - I think - used at the beginnings and ends of

all periods. At the time of new year the 4th corner of the

'earth' is located. It is time to detronise the old year and the

dark hair of a woman is used to wrap it up. This happens in the

5th 'dark period' beyond the 4th quarter, a time when gods are

born. The Chinese sign for number 5 is said to derive from the

picture of a thread-reel.

I.e. the same

method must be used to 'detronise' also the first half of a

double-hour of day-light. (We always count periods in even

numbers, a method used at first with 59 nights for a

double-month and later reused for all time periods - also

years.) When one 'ruler' is exchanged for another, a weak old

one going away and a newborn 'ruler' - also weak - is arriving,

there is room for freedom. The power from above is limited

because of weakness ...

|

Taviri

To

turn around. Vanaga.

Key,

lock, to turn a crank. Hakataviri, a pair of

compasses. T Mgv.: taviri, a key, a lock, to

lock, to twist. Mq.: kavii, a crank; tavii,

to twist, to turn. Ta.: taviri, a key, to

turn, to twist. The element viri shows that

the primal sense is that of causing a motion in

rotation. The key and lock significations are, of

course, modern and negligible. Churchill. |

The koro house 'caught

fire', a description reminiscent of how the Maya and Aztec

peoples symbolically cleaned the table. I think the house did

not ignite by itself, somebody caused the fire:

... When it was

evident that the years lay ready to burst into life, everyone

took hold of them, so that once more would start forth - once

again - another (period of) fifty-two years. Then (the two

cycles) might proceed to reach one hundred and four years. It

was called 'One Age' when twice they had made the round, when

twice the times of binding the years had come together. Behold

what was done when the years were bound - when was reached the

time when they were to draw the new fire, when now its count was

accomplished. First they put out fires everywhere in the country

round. And the statues, hewn in either wood or stone, kept in

each man's home and regarded as gods, were all cast into the

water. Also (were) these (cast away) - the pestles and the

(three) hearth stones (upon which the cooking pots rested); and

everywhere there was much sweeping - there was sweeping very

clear. Rubbish was thrown out; none lay in any of the houses ...

... According to

Codex Fejérváry-Mayer, a prehispanic Mesoamerican manuscript,

Xiuhtecuhtli was considered, 'Mother and Father of the Gods,

who dwells in the center of earth'. At the end of the Aztec

century (52 years), the gods were thought to be able to end

their covenant with humanity. Feasts were held in honor of

Xiuhtecuhtli to keep his favors, and human sacrifices were

burned after removing their heart ...

Although it is not stated in these

two accounts that houses were burnt, I remember having read

somewhere that the Maya each 52 years destroyed their houses to

build new ones, which I think is a good way to keep the art of

housebuilding alive.

"In the arabesque of

interlaced motifs, one can mark those where the theme of

'pulling down the structure' is in evidence. The powerful Maori

hero Whakatau, bent on vengeance,

laid hold of the end

of the rope which had passed round the posts of the house, and,

rushing out, pulled it with all his strenght, and straightaway

the house fell down, crushing all within it, so that the whole

tribe persihed, and Whakatau set it on fire.

This is familiar. At

least one such event comes down dimly from history. It happened

to the earliest meetinghouse of the Pythagorean sect, and it is

set down as a sober account of the outcome of a political

conflict, but the legend of Pythagoras was so artfully

constructed in early times out of prefabricated materials that

doubt is allowable.

The essence of true

myth is to masquerade behind seemingly objective and everyday

details borrowed from known circumstances ..." (Hamlet's Mill)

The name of the Maori hero,

Whakatau, certainly should be divided into haka and

tau, where haka is the causative prefix.

Whakatau means 'to make tau'. We are here close to

why Metoro said toa tau-uru for the

measures of the night, I think.

In Métraux I just (synchronously)

happened to read about the crucial word uru:

"The low entrances

of houses were guarded by images of wood or of bark cloth,

representing lizards or rarely crayfish.

The bark cloth

images were made over frames of reed, and were called

manu-uru, a name given also to kites, masks, and masked

people ..."

The lizard (moko) and the

crayfish (ura) seem to be interchangeable, both having

their place at the entrance of the 'house' (i.e. at e.g. new

year). The crayfish is red and therefore food for the gods who

will appear at the feast.

... In the romance

of Diarmuid and Grainne, the rowan berry, with the apple and the

red nut, is described as the food of the gods. 'Food of the

gods' suggests that the taboo on eating anything red was an

extension of the commoners' taboo on eating scarlet toadstools -

for toadstools, according to a Greek proverb which Nero quoted,

were 'the food of the gods'. In ancient Greece all red foods

such as lobster, bacon, red mullet, crayfish and scarlet berries

and fruit were tabooed except at feasts in honour of the dead.

(Red was the colour of death in Greece and Britain during the

Bronze Age - red ochre has been found in megalithic burials both

in the Prescelly Mountains and on Salisbury Plain.) ...

|

Uru,

úru-úru Uru. 1. To lavish food on those who have contributed to the

funerary banquet (umu pâpaku) for a family member (said of the

host, hoa pâpaku). 2. To remove the stones which have been heated

in the umu, put meat, sweet potatoes, etc., on top of the embers,

and cover it with those same stones while red-hot. 3. The wooden tongs

used for handling the red-hot stones of the umu. 4. To enter into

(kiroto ki or just ki), e.g. he-uru kiroto ki te hare,

he-uru ki te hare. 5. To get dressed: kahu uru. Vanaga.

Uruga. Prophetic vision. It is said that, not long before the

first missionaries' coming a certain Rega Varevare a Te Niu saw their

arrival in a vision and travelled all over the island to tell it:

He-oho-mai ko Rega Varevare a Te Niu mai Poike, he mimiro i te po

ka-variró te kaiga he-kî i taana uruga, he ragi: 'E-tomo te haûti i

Tarakiu, e-tomo te poepoe hiku regorego, e-tomo te îka ariga koreva,

e-tomo te poporo haha, e-kiu te Atua i te ragi'. I te otea o te rua raá

he-tu'u-hakaou ki Poike; i te ahi mo-kirokiro he-mate. Rega

Varevare, son of Te Niu, came from Poike, and toured the island

proclaiming his vision: 'A wooden house will arrive at Tarakiu (near

Vaihú), a barge will arrive, animals will arrive with the faces of eels

(i.e. horses), golden thistles will come, and the Lord will be heard in

heaven'. The next morning he arrived back in Poike, and in the evening

when it was getting dark, he died. Vanaga.

Uru manu. Those who do not belong to the Miru

tribe and who, for that reason, are held in lesser

esteem. Úru-úru. To catch small fish to use as bait.

Uru-uru-hoa. Intruder, freeloader (person who enters someone

else's house and eats food reserved for another). Vanaga.

1.

To enter, to penetrate, to thread, to come into port (huru);

uru noa, to enter deep. Hakauru, to thread, to

inclose, to admit, to drive in, to graft, to introduce, penetrate, to

vaccinate, to recruit. Akauru, to calk. Hakahuru, to set a

tenon into the mortise, to dowel. Hakauruuru, to interlace;

hakauruuru mai te vae, to hurry to. 2. To clothe, to dress, to put

on shoes, a crown. Hakauru, to put on shoes, to crown, to bend

sails, a ring. 3. Festival, to feast. 4. To spread out the stones of an

oven. Uruuru, to expand a green basket. 5. Manu uru, kite.

Uruga (uru 1).

Entrance. Churchill.

Uru, make even. Kapingamarangi. |

|

URU

This word usually means breadfruit (=

'skull'). Its fruit resembles a human skull, and

it is a most important fruit because of this and

because of its nutricious value. However, on

Easter Island breadfruit couldn't grow and

another plant seems to have served as a

substitute, Solanum nigrum, called

poporo:

This

plant is - according to bishop Jaussen's

documentations of what Metoro Tau'a Ure

told him - one species of the interesting family

of plants named Solanum. It was used for

obtaining colour for tattooing. There are though

several different types of glyphs showing this

plant, and possibly not all of these types imply

colour for tattooing. Every gift from nature was

taken care of to the utmost.

Barthel suggests the plant to be Solanum

nigrum. As nigrum means black, the

glyph perhaps was used for 'black'. Barthel

points out that on the Marquesas they counted

the fruits from the breadfruit trees in fours,

perhaps thereby explaining the four 'berries' in

this type of glyph.

The

breadfruit did not grow on Easter Island and the

berries of Solanum nigrum were eaten in

times of famine.

Barthel also informs us that the Maori singers

in New Zealand, where the breadfruit did not

grow, 'translated' kuru (= breadfruit) in

the old songs, from the times when their

forefathers lived in a warmer climate, into

poporo (= Solanum nigrum). And

according to Metoro the type of glyph

above stood for poporo.

Barthel further compares with the word koporo

on Mangareva. The poor crop of breadfruits at

the end of the harvest season was called

mei-koporo, where mei stood for

breadfruit. On other islands breadfruit was

called kuru, except on the Marquesas

which also used the word mei. Koporo

was a species of nightshade. |

I think we may be fairly certain

that uru in toa tauuru means that there is a kind

of masquerade - that the glyphs are not to be understood as real

tóa warriors hanging upside down (îka, fish). They

are not human beings temporarily dead soon to quicken again like

rau hei (mimosa branches). The

toa tauuru are instead important elements in the 'house

frame' of the night, i.e. the true meaning is masked by the

toa glyphs.

I imagine that there may

be some kind of description of the establishing of a new 'house' frame for the year among the glyphs at the beginning of side b. If so,

then the GD25 (pure) glyphs could be these key glyphs:

|

|

|

Ab1-6 |

Ab1-7 |

| i

ako te vai |

|

Ab1-15--17 |

|

|

Ab1-14 |

Ab1-18 |

| e honu paka |

e pure ia |

|

|

|

Ab1-68 |

Ab1-69 |

| no gagata |

apaki pure |

We should (temporarily) finish here by repeating

what I earlier have written about GD25 in the glyph dictionary:

|

GD25

|

pure |

Metoro usually said pure(ga) or

hare pure at this type of glyph. |

|

|

|

1.

GD25 could very well illustrate a pure

=

cowrie, but perhaps rather a bivalve with

two shells in general. The clam is not lying down

the way we usually see it, but this presumably is

just a way to reduce the space needed for the glyph

(cfr rei miro GD13 which is also standing on

its short end).

Metoro, on the other hand,

may have seen something else. Because his hare

pure should mean church, chapel or 'house to

pray', i.e. pure = prayer (though this seems

not to be a loan from the English language). In

Metoro's frame of reference the glyph perhaps is

illustrating an open mouth.

2.

However, neither of these two explanations is the

primary one. Instead we have two bent henua

(GD37), meeting at two points, like the hinges of a

clam.

Together this means a

year,

the two bent henua being the half-years

'winter' and 'summer'. The hinges are the solstices

(though perhaps in ancient times the equinoxes - a

more resonable interpretation because of the sharp

bends = quick changes of the sun).

There is

a myth supporting the interpretation that our

(temporal) world is like a clam, see

GD33.

But the interpretation of GD25 as hare is

more reasonable. Because "to enter a war canoe from

either the stern or the prow was equivalent to a

'change of state' or 'death'. Instead, the warrior

had to cross the threshold of the side-strakes as a

ritual entry into the body of his ancestor as

represented by the canoe." (Starzecka)

The

hare paega on Easter Island therefore had their

entrances in the middle of one of the long sides of

the 'canoe'. And the foundation stones of a hare

paega are similar to the henua in GD25.

The hare pure as 'the abode of the gods' is a

possible reading of GD25; hare can be

translated as structure and in the structure of

hare pure the openings are at the 'stem' and the

'prow'. A canoe is also a structure and hare

paega is like an overturned canoe (with openings

for the gods at the stem and prow).

"Our old

men said that the stars were the cause of good or

bad seasons which are influenced by the mana

of their rays. Thus the division of the year,

kau-penga, where named after certain stars." (A

Maori scholar according to Makemson.)

3.

More exactly defined the left henua seems to

be the time/space of the year when

the

Pleiades are visible in the sky (Matariki

i nika) and the right henua the other

half of the year, 'summer' (Matariki i raro).

In

Tahua a more technical description of

Matariki i nika is found:

The

right part of this type of glyph incorporates the

sky (with the two horns of the moon appearing behind

the 'head' of ragi) and the sign for

downwards shining light (tea).

The head

of rangi is leaning towards the right in

harmony with the leaning of henua, both

representing the bent shape of the sky above (the

upper valve of the clam).

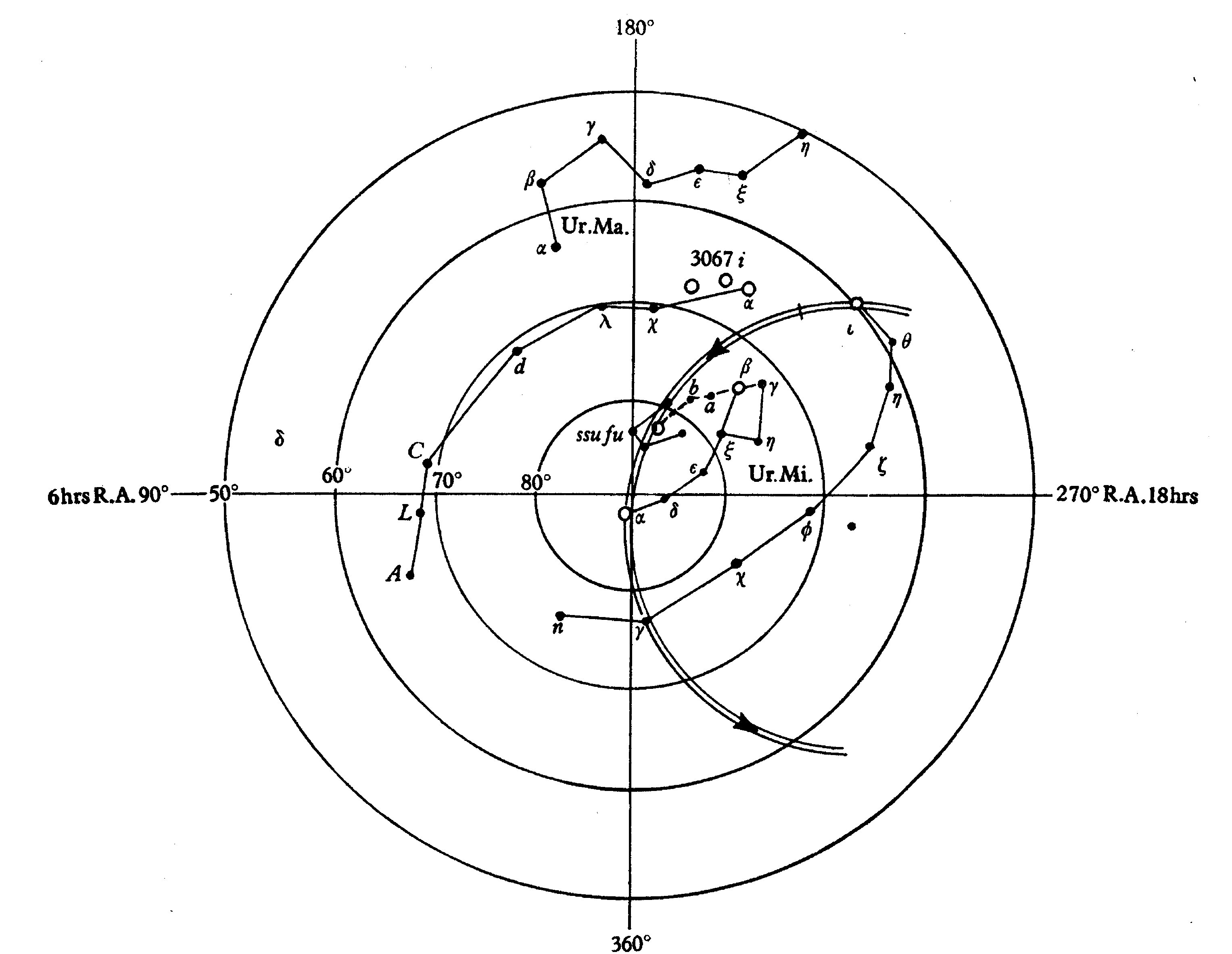

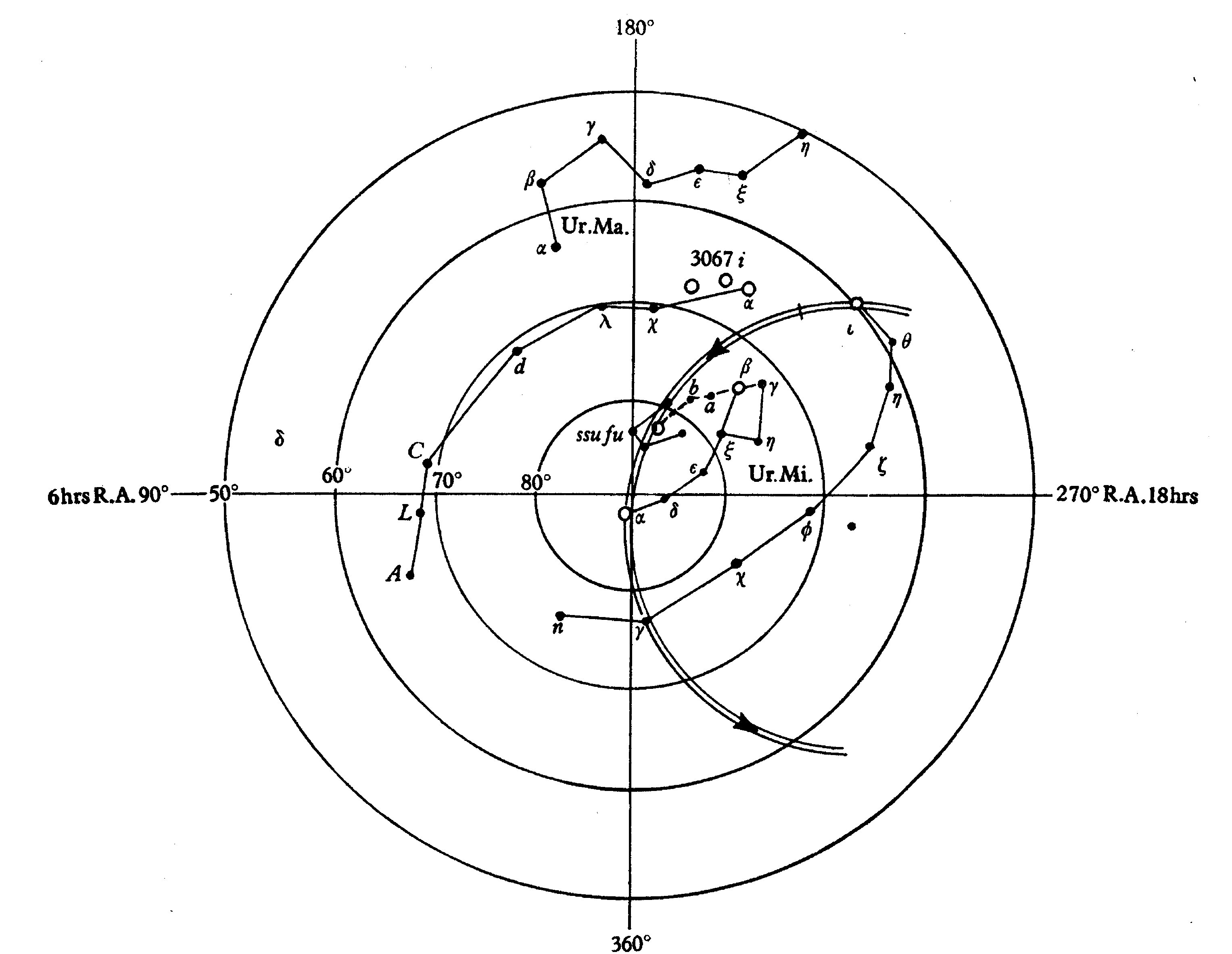

Ultimately there may be a Chinese influence

behind all this, because the Chinese regarded the

northern cap of the sky as the most important part,

where the 'Emperor' ruled (at the north pole which

did not revolve but was steady as a rock). The

Emperor's abode was defined by two 'walls' or chains

of stars:

The north pole slowly moved in a

circle, however, inside these walls of Ming

Thang, The Bright Palace, 'the mystical

temple-dwelling which the emperor was supposed to

frequent, carrying out the rites appropriate to the

seasons'. (Ref.: Needham 3) |

|