|

TRANSLATIONS

There are 10 periods for the daylight according to Tahua (Aa1-16--36), as counted by the number of tapa mea (GD55). There are also 10 periods in the year before sun 'leaves' (Aa1-1--10), if we count by the number of glyphs. Though the glyphs may represent double periods, and then presumably 2 * 14 = 28 nights (those nights in the month when moon is visible). Maybe also the 10 tapa mea in the daylight calendar are to be counted as double periods. Such glyphs as Pa5-37 suggest that:

Furthermore, there was a tendency to compare the diurnal cycle with the yearly cycle and try to establish similarities. Once the Polynesians appear to have had 10 months: ... A connection between the new year and the harvesting of crops reminiscent of an earlier period when the evening appearance of the Pleiades in the east more nearly coincided with the arrival of the Sun at the autumnal equinox is seen in the prolonged Hawaiian ceremonies ushering in the new year. For in the month September-October, while the old year still had two months to run, announcement was made to the people by placing a certain signal outside the temple walls that the new year had begun ... Sun (summer, Kuukuu) disappears at crop time ... ... The important time of year in New Zealand was the tenth month when the sweet potato crop was harvested and stored in pits against the unproductive months of the winter. The eleventh and twelfth months were considered completely negligible ... Maybe also Sun was stored in a pit during the two 'negligible' months of winter? In the conceptual model where celestial 'persons' rise from 'pits' at the eastern horizon there surely must be a 'storing in pits' at the western horizon ... Though 10 months at some time became 12 months: ... From the natives of South Island [of New Zealand] White [John] heard a quaint myth which concerns the calendar and its bearing on the sweet potato crop. Whare-patari, who is credited with introducing the year of twelve months into New Zealand, had a staff with twelve notches on it. He went on a visit to some people called Rua-roa (Long pit) who were famous round about for their extensive knowledge. The name Rua-roa (Long pit) certainly alludes to solstice time. Whare-patari means 'the house of the Magellanic cloud'. ... According to Tutakangahu, the sage of the Tuhoes, the Maori priests gathered young shoots of food plants and offered them on special altars to those stars which were believed able to provide abundance by influencing the growth of both wild and cultivated products as well as the multiplication of fish and game. The priests then intoned rituals beseeching the stars to bestow a plentiful supply: Tuputuputu atua / Ka eke mai i te rangi e roa e, / Whangainga iho ki te mata o te tau e roa e. Magellanic Cloud [Tuputuputu is another name for the Magellanic Clouds], sacred one, / Mounting the heavens, / Cause all the new year's products to flourish. In the succeeding stanzas the prayer was addressed to Atutahi (Canopus), Takurua (Sirius), Whanui (Vega), and other food-bringing stars in turn, the second and third lines being repeated for each star. It will be noticed that these food-giving stars are not in general the same as the stars which governed the months ... They inquired of Whare how many months the year had according to his reckoning. He showed them the staff with its twelve notches, one for each month. They replied: 'We are in error since we have but ten months. Are we wrong in lifting our crop of kumara (sweet potato) in the eighth month?' Whare-patari answered: 'You are wrong. Leave them until the tenth month. Know you not that there are two odd feathers in a bird's tail? Likewise there are two odd months in the year.' The grateful tribe of Rua-roa adopted Whare's advice and found the sweet potato crop greatly improved as the result. We are not told what new ideas he acquired from these people of great learning in exchange for his valuable advice. The Maori further accounted for the twelve months by calling attention to the fact that there are twelve feathers in the tail of the huia bird and twelve in the choker or bunch of white feathers which adorns the neck of the parson bird ... Conceptually there seems to be a connection between neck and tail. I believe the explanation is that at crop time the 'head' is taken (by cutting the 'neck') and that will be the end ('tail') of the old 'bird'.

... There are other traces of an ancient year of ten months. The Marquesans, for example, termed a year of ten lunar months one puni or 'round'. Puni was the name for year in Easter Island. According to the ancient history of Kanalu some Hawaiian tribes assigned fourteen months to the year, or hookahi puni ma eha malama, one puni consisting of ten months plus four odd months ... There are 14 glyphs before we arrive at the 'break' in Aa1-15:

... The connections between the digging stick, cuckoo and summer appear also among the Maori: 'The Maori recognized two main divisions of the year: winter or takurua, a name for Sirius which then shone as morning star, and summer, raumati or o-rongo-nui, 'of the great Rongo', god of agriculture. They occasionally recognized spring as the digging season koanga, from ko, the digging stick or spade. The autumn or harvest season was usually spoken of as ngahuru, 'tenth' (month), although it was considered to include also the last two months of the year. Mahuru was the personification of spring ...

... The Maori term o-rongo-nui was undoubtedly applied to summer as in phrases such as te ra roa o te marua-roa o te o-rongo-nui, 'the long days (ra, Sun) of the summer solstice'; but it was also extended to cover the months of spring and early summer as well as those of late summer and fall. This is evident from such statements in the legends as: 'That bird is a cuckoo, and that is the bird of matahi o te tau o o-rongo-nui', i.e., of the first month of the summer season, although in New Zealand the cuckoo, like the robin in the north temperate zone, was the harbinger of spring. Also, 'Hine-rau-wharangi' was born in the month Ao-nui (first light) of the o-rongo-nui'. Among the Takitumu tribe Ao-nui was the name for May-June, the first month of the year which belonged to late fall or early winter. Rongo was the name for June in the Chatham Islands and began the Moriori year ... The calendar of the night (Aa1-37--48) has 12 periods, as counted by the number of glyphs. At Aa1-43 (= 42 + 1) the new 'day' begins:

This henua (GD37) has the short ends drawn inwards (as if indicating a time of famine), probably a sign of darkness (the daylight has not yet appeared). Such glyphs as Ha6-7 (showing a double period) may indicate that Aa1-43 contrariwise is not to be counted double:

Number 43 (in Aa1-43) is the result of 15 glyphs for the year (Aa1-1--15) added to 10 glyphs for the first half of daylight, up to and including Aa1-25, added to the 'death glyph' Aa1-26, added to 10 glyphs with sinking sun and dusk (Aa1-27--36), added to then 'ante midnight' 6 glyphs:

The rightmost numbers are sums which do not include the glyphs where the 'break' between periods occur (black-marked by me). The numbers at left reflect the marks on tapa mea during daytime. During nighttime the numbers reflect that the sign Y on top of t˘a tauuru (GD47) probably indicates double. Counting the 'day' as starting with Aa1-44 we arrive at 8 periods during nighttime and 20 (= 2 + 8 + 8 + 2) during daytime, i.e. 8 + 20 = 28 periods for a 'day'. For the 'night' remains 6 double periods = 12 periods. The sum of 'day' and 'night' will be 28 + 12 = 40. Counting the 'day' by way of the marks on tapa mea we get: 0 + 24 + 1 + 6 = 31, to which presumably we ought to add 8 (for post midnight) and thereby reach 39. One is missing (one got away) if we expected to reach 40. Line Aa1 has 90 glyphs and if we subtract the first 48 glyphs - used for the year, the X-area, the daylight calendar and the night calendar - we have 42 remaining glyphs, beginning with:

... Aa1-52 is number 52 and 52 * 7 = 364. Aa1-53 may illustrate old and new year (around winter solstice). Aa1-54 we remember from Aa1-15:

... In Aa1-15 we saw a break between the left and right parts. The break in the night occurs between Aa1-42 and Aa1-43 because there are 12 'hours' in the night and an even number of glyphs cannot have a break in the middle - the middle is two glyphs. Could Aa1-42 be the end of the sequence of glyphs which are 'outside' the 200π?

If that is so, then the meaning of this sign could be that with Aa1-43 'life' (sun) is reborn, which could allude to side a being used for 'mapping' the 'solar life' (over the year). 10 glyphs beyond Aa1-42 we find Aa1-52:

52 = 364 / 7 and the old year will soon meet his end ... Regarding Aa1-54 as the end of a part of the text, we find that the remaining glyphs in line Aa1 are 90 - 54 = 36. If Aa1-53 represents old and new year, then - I guess - the 4 glyphs Aa1-49--52 ought to represent the 4 quarters of the old year. 3 quarters (Aa1-49--51) have 'passed away' we can read, while the 4th and last quarter miraculously instead has been saved (got away) onboard a vessel. ... Why are there only 3 Pure emitted by Hotu Matua? Shouldn't it be an even number? As O, Ki, and Vanangananga were three of a quartet we miss Pure Henguingui ... ... RAP. henguingui is synonymous with MGV. henguingui 'to whisper, to speak low' and goes back to west Polynesian forms (SAM. fenguingui 'to talk in a low tone'; UVE. fegui 'murmurer') ... ... Now it becomes obvious why we should count 3 + 1 = 4:

I was probably wrong when I suggested that Va was the new 'moa' (or ariki), because at borders it is dangerous to open the mouth. Instead the 'missing' one, Pure Henguingui (the whisperer) must have survived. As to the reason why side a has 670 = 200π + 42 glyphs, it is possible (as suggested above) that Aa1-43 is the beginning of a 670 - 42 = 628 (200π) glyphs long journey of the sun, ending with Aa8-85:

The day + night calendar presumably has been created with the yearly journey of the sun in mind. Therefore it is noteworthy that at the beginning of the new 'day' there is a canoe (vaka, GD48):

Adding 42 glyphs to Aa1-13 we reach Aa1-55, i.e. the point from which a new period begins (given that Aa1-54 means the end of a period):

Aa1-13 (GD18, niu) indicates that the 'fire' has been 'stamped out' (rei). All 4 cardinal henua are just ghosts:

... there are 4 'beams' of light (like spooks - or spikes - in a wheel). spike ... A. ear of corn ... inflorescence of sessile flowers on a long axis ... B. lavender ... L. spīca ... rel. to spīna spine ... lave ... wash, bathe; pour out ... refresh ... Probably we should understand GD18 (niu) as the upside down 'king' (ariki, GD63) of light (Tane):

The ariki (GD63) is standing on top of the events of all 4 'directions' of his kingdom. He symbolizes 'reality' in full force, whereas his upside down image (GD18) has only 'spooky' power. The open ends of the 'quartet' on top is contrasted with the firmly closed ends of the 'quartet' at bottom. The 4 directions in Aa1-13 probably are ordered from left bottom and clockwise, i.e. with the colours white (the colour of the moon), pink (the colour of premidsummer sun), black (when Kuukuu the planter 'dies') and red (the colour of blood). The top spooky 'branches' represent summer (life of sun on land). We should compare with the t˘a-glyphs (GD47) where probably the top Y represents the spooky image of daytime: ... Metoro's name niu for this glyph type probably suggests the 'land of the past' in the same way as Hiva does, because the coco palm no longer grows on Easter Island ... ... Another idea: In Hb9-45 the top has the structure 3 + 1, whereas in Aa1-13 it has 4:

The 4th limb in Hb9-45 is different, not 'spooky' and presumably has a sun symbol at right on the 'knee'. Maybe the 'kava' limb is expressing how the new chief dies and then lives again. Like lightning he strikes the ground, thunder rolls and his strength is regained ... In Heyerdahl 6 I found another indication that 'open' means 'death' (or 'spirit'):

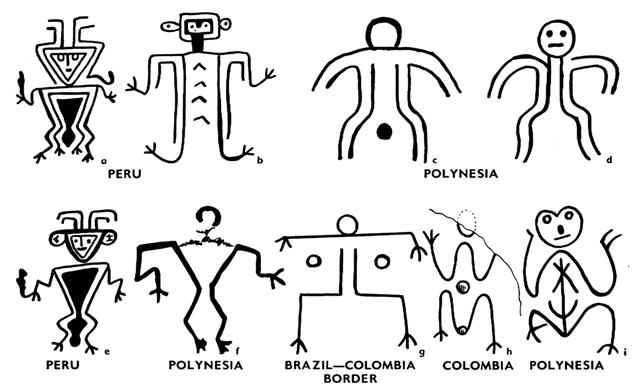

"Figs. a, b and e are Peruvian spirit emblems painted or embroidered on the burial gifts formed like sails ... Figs. c and d are petroglyphs of a type common in the Marquesas and Society Islands ... This peculiar type of Polynesian petroglyph represent, like so many of the Peruvian spirit emblems, an anthropomorphic figure drawn in two parallel lines in such a way that the body is not joined at the hips. Fig. f is a petroglyph from Kauai, Hawaii, reproduced by Bennett ... who describes it as 'triangular body not joined at the hips.' He further says ... of the local anthropomorphic figures in Kauai petroglyphs: 'Two, three, and four toes are found, with three as typical.' Both the triangular body, gaping hips, crooked arms, and a strange number of toes and fingers agree remarkably well with spirit emblems in early Peru ..." ... At the front wall of the house she caught sight of some poor human beings, their faces were one broad grin - they had no entrails. Thus she now sat there. At last, after some time, the Moon entered, and he now said: 'Look at those poor fellows there without entrails, they are those my cousin has deprived of their entrails!' He had given one of them something to chew, but as usual it fell down through him, where the entrails had been removed. Whenever they swallowed something, they had chewed a little, it fell right through them ... At Aa1-56 (GD16, vai) we should compare with the beginning of Sunday (Hb9-18 respectively Pb10-30):

Reasonably, the beginning of one period (week) should begin in a similar way as another period (year). Let us end this chapter with landing on terra firma and review two earlier pictures:

... Before midsummer the glyphs describe stylized arms (pushing the sun / sky up) and therefore it cannot be 'knees' - it must be 'elbows'. At midsummer there is a more fundamental reversal than shifting the 'elbows' from left to right (as in a vertically placed mirror), there is a reversal from going up to going down (a reflection as if in a horizontally placed mirror) ... If we compare the day time (according to Tahua) with the 'summer' (as seen above), we note the similarity in sun 'dying' during the 'after noon':

... We should also note the differences in the 'death' glyphs:

In the diurnal cycle the impression is that a 'person' is waving goodbye and then we see his arm turned into bone and his 'soul' rising while his earthly remains are marked by a stone. In the yearly circuit the arm is cut across (hatchmarked) to indicate darkness, or possibly caught in the strands of black hair, and after that we see just a grand burial stone. Presumably we should interpret the difference between GD45 and GD73 as due to the fact that in GD45 the 'soul' already is in the sky, whereas in GD73 the 'soul' is rising:

4 double months (the 'knee', or rather 'elbow', at left means a double period) before midsummer and 2 double months after midsummer give us 2 * 6 = 12 months for sun (Kuukuu) to live. In the Aztec calendar the sun has 14 * 6 = 84 midsummer days:

At the 'back' (tu'a) there seems to be 42 days. Perhaps the 42 first glyphs in line Aa1 correspond to those 42 days. 200π + 42 = 670 glyphs are too many for a cyclic yearly tour with the sun canoe. The 42 must therefore belong to the earlier cycle. This year's cycle starts at Aa1-43:

We have seen that Aa1-43 is unique among the henua (GD37) in the Tahua text. A table summarized the main glyphs of this kind:

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||