|

TRANSLATIONS

The Japanese people is a hard working people. Yesterday evening when I on TV watched the Aki Basyoo sumo tournament the commentator explained that there were many spectators because it was Sunday - the other days in the week people couldn't get away from their jobs. Furthormore, it was the 8th day of the 15-day tournament, i.e. there were much people on the 1st, the 8th and the final day. The arrangement was always to have the final on a Sunday. This made me think. We have met 8 as an important cyclic number, for instance from OgotemmÍli: ... The most important of all drums, he said, was the armpit drum. The Nummo made it. It consists of two hemispherical wooden cups connected through their centres by a slender cylinder. It is like an hour-glass with a very long narrow neck. With this instrument tucked between his left arm and armpit, the drummer, by pressing on the hollow structure of thin wood, can tighten or relax the tension on the skins and so modify the tone. 'The Nummo made it. He made a picture of it with his fingers, as children do today in games with string.' Holding his hands apart, he passed a thread ten times round each of the four fingers, but not the thumb. He thus had forty loops on each hand, making eighty threads in all, which, he pointed out, was also the number of teeth of his jaws. The palms of his hands represented the skins of the drum, and thus to play on the drum was, symbolically, to play on the hands of the Nummo. But what do they represent? Cupping his two hands behind his ears, OgotemmÍli explained that the spirit had no external ears but only auditory holes. 'His hands serve for ears,' he said; 'to enable him to hear he always holds them on each side of his head. To tap the drum is to tap the Nummo's palms, to tap, that is, his ears.' Holding before him the web of threads which represented a weft, the Spirit with his tongue interlaced them with a kind of endless chain made of a thin strip of copper. He coiled this in a spiral of eighty turns, and throughout the process he spoke as he had done when teaching the art of weaving. But what he said was new. It was the third Word, which he was revealing to men.

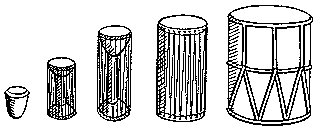

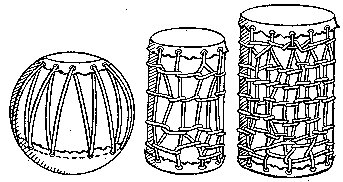

My intuition has told me that counting backwards from the largest drum to the special round one we ought to find Thursday, the day we eat round pancakes. But there are 8 drums, not 7 as the number of days in a week. That problem has ticked at the back of my head without solution. The sumo program delivered the solution: Given a start on Sunday with number 1, then the Sundays will arrive at 8, 15, 22 and 29. 15 is the full moon night, I guess, and 29 probably explains why Tahua as 46 * 29 = 1,334 glyphs. 29 is 4 weeks (a month), but the 1st day of next 4-week period must be located on a Sunday too, i.e. number 29 must be equal to number 1. ... The Maya New Year started with 1 Pop, the next day being 2 Pop, etc. The final day of the month, however, carried not the coefficient 20, but a sign indicating the 'seating' of the month to follow, in line with the Maya philosophy that the influence of any particular span of time is felt before it actually begins and persists somewhat beyond its apparent termination ... 28, according to the new interpretation, is not only the number of nights the moon shines with light from the sun, but 28 is of necessity the number of days in a month in order for the clockwork to function properly. 29 is equal to 1 and 8 is also equal to 1. A week begins on Sunday and ends on Sunday, but the latter Sunday is also the beginning of the following week. The 1st drum above is equal to the 8th and last one. With the decimal system 10 means the number following after 9. With a system based on 8 the number following 7 will be 10. The 2nd and 3rd drums equals sun and moon, because counting backwards from the 8th drum - going backwards in time because growth proceeds from little to great - we arrive there given that the 8th drum is Saturn. The end of the week must be ruled by Saturn and therefore Saturday is also the 1st day of next week. The two armpit drums (sun and moon) represent the drums of Nummo: ... The most important of all drums, he said, was the armpit drum. The Nummo made it. It consists of two hemispherical wooden cups connected through their centres by a slender cylinder. It is like an hour-glass with a very long narrow neck ... We leave that for the moment. Let us instead return to the hau tea glyphs. We can be certain that side a of Tahua describes the journey of the sun over the year, while side b documents the journey of the moon over the same year. Extending the table we have just created to include also the hau tea on side b we should see that they are parallel to those on side a. We begin like this:

The right vertical line is longer in the quartet of hau tea on side b, a sign that we are still in the 1st part of the year (according to what we have earlier established for hau tea glyphs on side b). We should also note that in Ab1-3 the glyph is leaning backwards, a sign which presumably is 'parallel' with a glyph leaning fordwards when a 'sunny' period is described, for instance in the quartet:

The form of these forward leaning figures maybe is designed to allude to viri as if seen in a mirror.

The right vertical lines in the 2nd quartet glyphs of hau tea on side b are no longer the longest. A reversal occurs from Ab2-52 to Ab3-46 and the reversal, I guess, is located at midsummer. Between Aa5-63 and Aa7-79 a gap occurs. Maybe it should be occupied by on of these glyphs (Aa6-2 respectively Aa7-29), also Aa1-11 and Aa1-34 are heavily marked:

My vote goes to Aa7-29, because a shark should be expected here. For instance, at autumn equinox according to my preliminary interpretation of London Tablet there is a glyph (Kb2-107) with a similar head:

Perhaps its signs should be read as 2 + 2 = 4 meaning the 4th quarter of the year? Furthermore, Ab4-24 seems to be the wrong glyph at that place. A more complicated and proper glyph is Ab4-30:

Not so long ago I defined hau tea to include glyphs with curved triple lines:

There remains 1 glyph on side a and 7 on side b:

The 2nd half of the moon year (as shown by short right vertical lines) could mean the 2nd half of the half-year from summer solstice to winter solstice. The power of moon increases up to winter solstice. The result, it seems, is that spring is not discussed on side b, while on side a the time before midwinter is not discussed. We remember the pattern in the Peruvian ceque structure:

... I (Chinchay-suyu) was the 'white' quarter where the Inca rulers lived, II (Anti-suyu) was a mixed quarter, III (Colla-suyu) was also a mixed quarter, and then IV (Cunti-suyu) was 'black') ... 'White' in the 1st quadrant and 'black' in the 4th in Peru emphasizes the power of sun (the light), but at the same time acknowledges that the origin of sun is in the 4th 'black' quadrant. In Tahua the power of 'black' in the 4th quadrant is harmonized by a balance with 'red' in the 2nd quadrant, where the power of sun clearly is at his strongest. The 1st and 3rd quadrants are mixed quarters, 'blue'. The Incas were not so balanced: "When we review the Andean Con-Tici-Viracocha myths we find that the ancient Peruvian solar religion cannot justly be referred to as pure sun-worship. In fact, the claim has been raised in some quarters (Means 1920 a, p. 27; etc.) that only the Incas were the actual spreaders of the genuine sun-cult in Peru, the pre-Inca religion having been essentially an ancestor-cult focused above all around a creator-god. We have seen, however, that this creator-god under his various names is intimately associated with the appearance of the light and the sun, and that some of his pre-Inca names are related to the terms for these conceptions. The relationship between the creator-god and the sun is also apparent from numerous Tiahuanaco works of art, not least the central figure on the monolithic Gateway of the Sun. Evidently in later Inca time the sun itself was raised to a much greater importance, but even then not as the sole supreme deity ..." (Heyerdahl 6) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||