|

TRANSLATIONS

Tagaroa Uri (possibly 'Green Tangaroa') is

located in spring:

|

...

Barthel has given us the following data:

|

Vaitu Nui

(April) |

1-2 |

Hora Iti

(August) |

9-10 |

Koro

(December) |

17-18 |

|

Vaitu Potu

(May) |

3-4 |

Hora Nui

(September) |

11-12 |

Tuaharo

(January) |

19-20 |

|

Maro

(June) |

5-6 |

Tangaroa Uri

(October) |

13-14 |

Tehetu'upu

(February) |

21-22 |

|

Anakena

(July) |

7-8 |

Ruti

(November) |

15-16 |

Tarahau

(March) |

23-24 |

The twelve

Rapanui months are divided into

half-months according to the numbers, which

refer to the order established by the voyage

of the dream soul:

|

1 |

Nga Kope Ririva Tutuu Vai A Te

Taanga |

9 |

Hua Reva |

17 |

Pua Katiki |

|

2 |

Te Pu Mahore |

10 |

Akahanga |

18 |

Maunga Teatea |

|

3 |

Te Poko Uri |

11 |

Hatinga Te Kohe |

19 |

Mahatua |

|

4 |

Te Manavai |

12 |

Roto Iri Are |

20 |

Taharoa |

|

5 |

Te Kioe Uri |

13 |

Tama |

21 |

Hanga Hoonu |

|

6 |

Te Piringa Aniva |

14 |

One Tea |

22 |

Rangi Meamea |

|

7 |

Te Pei |

15 |

Hanga Takaure |

23 |

Peke Tau O Hiti |

|

8 |

Te Pou |

16 |

Poike |

24 |

Mauga Hau Epa |

... The

triple division of the Marquesan year yields

the segments August-November,

December-March, and April-July ...

... The months were also personified by the

Marquesans who claimed, as did the

Moriori, that they were descendants of

the Sky-father. Vatea, the Marquesan

Sky-parent, became the father of the

twelve months by three wives among whom

they were evenly divided ...

... A curious diversion appears in the month

list of the people of Porapora and

Moorea in the Society Islands, which

sheds light on the custom of the Moriori

who sometimes placed 24 figures in the canoe

which they dispatched seaward to the god

Rongo on new years day. The names of

the wives of the months are included,

indicating that other Polynesians besides

the Chatham Islanders personified the months

... |

As tangaroa.a oto

uta is the 2nd king on the list (of the year),

ko oto uta must be the New Year King. His

'dream stations' are nos. 11-12, i.e. Hatinga Te

Kohe and Roto Iri Are.

The Old

Year King has nos. 9-10 and according to my

interpretation of the beginning of side a in

Tahua he is characterized as 'dying':

|

|

|

Aa1-11 |

Aa1-12 |

| ihe

kuukuu ma te maro |

ki

te henua |

Kuukuu (resembling the 'flute' of the 'cuckoo

bird') presumably should be contrasted with

Kiukiu (the 'squeeking rat', Oto Uta).

Also his neck was broken, though later in the year

according to Manuscript E:

|

.. On the thirtieth day of the month of

October ('Tangaroa Uri'), Hotu

asked about the stone figure (moai

maea) named Oto Uta. Hotu

said to Teke, 'Where is the

figure Ota Uta (corrected in the

manuscript for Hina Riru)?

Teke

thought about the question and then said

to Hotu, 'It was left out in the

bay.'

...

The canoe of Pure O left on the

fifth day of the month of November ('Ruti').

After the canoe of Pure O had

sailed and had anchored out in the bay,

in Hanga Moria One, Pure

saw the figure, which had been lying

there all this time, and said to his

younger brothers (ngaio taina),

'Let's go my friends (hoa), let

us break the neck of this mean one (or,

ugly one, rakerake). Why should

we return to that fragment of earth (te

pito o te kainga, i.e., Easter

Island)? Let us stay in our (home)land!

... After the neck of Oto Uta had

been broken, Kuihi and Kuaha

arrived. They picked up the neck of King

Oto Uta, took it, and brought it

with them. They

arrived out in the bay, in Hanga Rau.

(There) Kuihi and Kuaha

left (the fragment). After the neck of

Oto Uta had been brought on land,

out in the bay of Hanga Rau, the

wind, the rain, the waves, and the

thunder subsided. Kuihi and

Kuaha arrived and told the king the

following: 'King Oto Uta is out

in the bay of Hanga Rau'. Hotu

said to his servant (tuura)

Moa Kehu, 'Go down to king Oto

Uta and take him up out of the bay

of Hanga Rau!' |

|

Hanga Rau

is the place where new life begins:

'... When Hotu's canoe had

reached Taharoa, the vaginal

fluid (of Hotu's pregnant wife)

appeared. They sailed toward Hanga

Hoonu, where the mucus (kovare

seems to refer to the amniotic sac in

this case) appeared. They sailed on and

came to Rangi Meamea, where the

amniotic fluid ran out and the

contractions began. They anchored the

canoe in the front part of the bay, in

Hanga Rau. The canoe of Ava

Rei Pua also arrived and anchored.

After Hotu's canoe had anchored,

the child of Vakai and Hotu

appeared. It was Tuu Maheke, son

of Hotu, a boy. After the canoe

of Ava Rei Pua had also arrived

and anchored, the child of Ava Rei

Pua was born. It was a girl named

Ava Rei Pua Poki ...' |

It

seems that the neck of the statue of King Oto Uta

was broken at summer solstice (late in November,

Ruti). If so, then

the event takes place at dream stations nos. 15-16 (Hanga

Takaure and Poike)

The breaking of the

neck is equivalent, I think, to breaking the power.

We remember Katinga Te Kohe (no. 11) at which

the dream soul of Hau Maka broke the 'kohe'

with her feet.

...

The

name 'Breaking of the kohe plant', which is

used in the same or nearly the same form in all of

the tradition, must refer to a special event.

*Kofe is the name for bamboo on most Polynesian

islands, but today on Easter Island kohe is

the name of a fern that grows near the beach ...

She broke the 'bamboo'

staff (old year ruler), to clear the way for Oto

Uta. Both at winter solstice and at summer solstice

the old rulership must be broken.

Once again 'From Honey to Ashes' has valuable

information to offer:

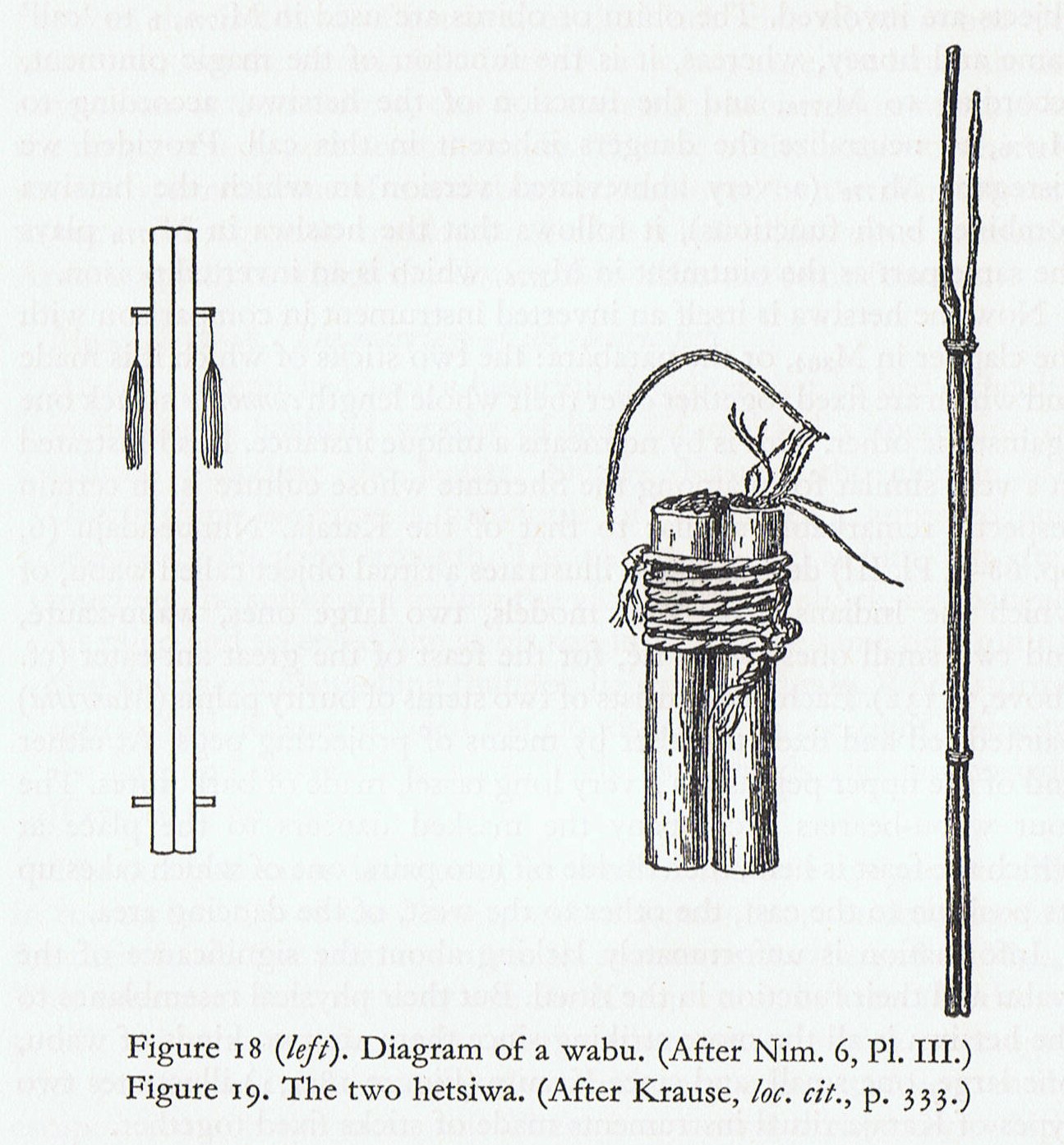

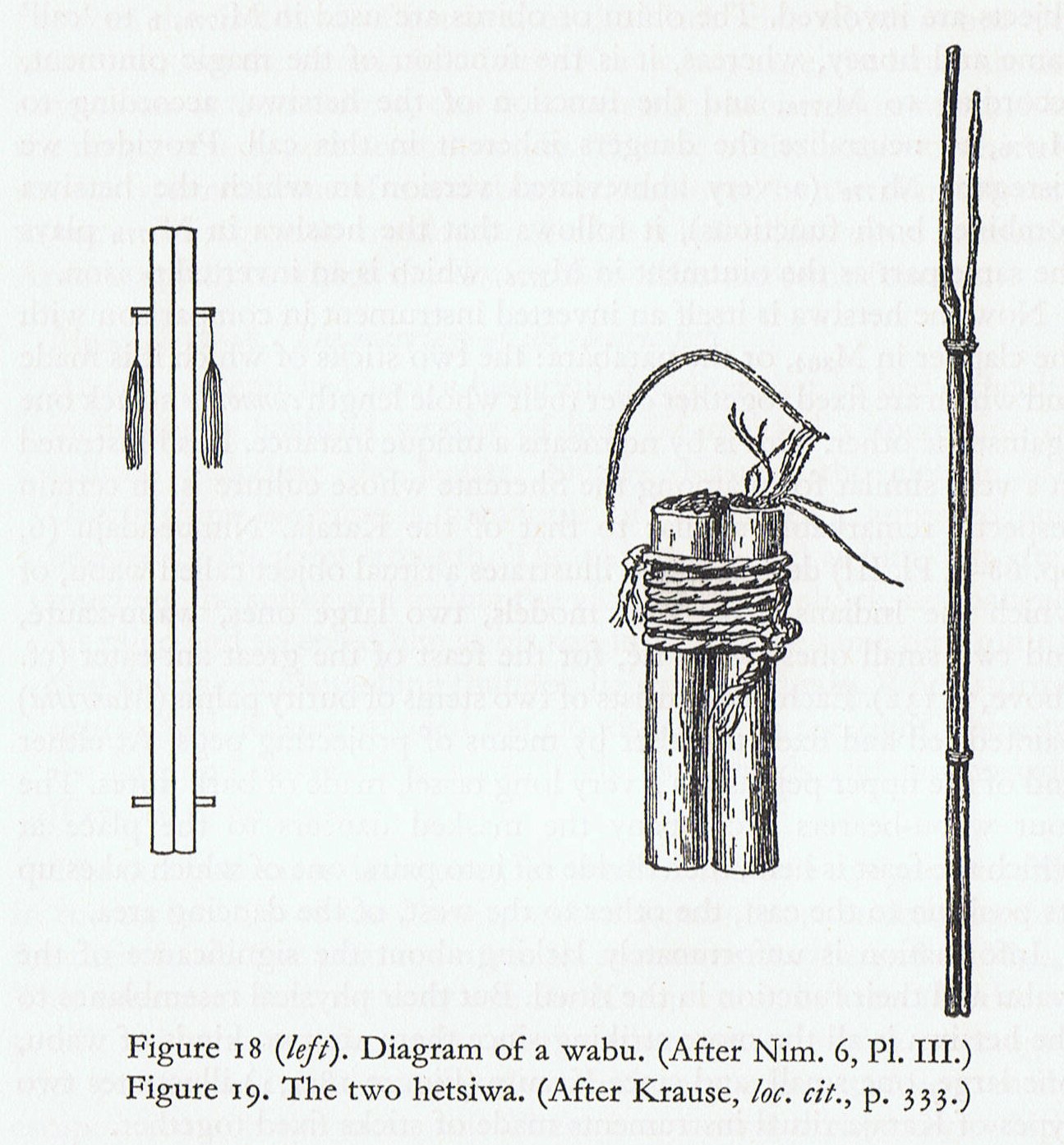

"... Information is unfortunately

lacking about the significance of the wabu

and their function in the ritual. But their physical

resemblance to the hetsiwa is all the more

striking since there are two kinds of wabu,

one large, one small, and since Krause ...

illustrates two types of Karaja ritual

instruments made of sticks fixed together,

In the present state of knowledge,

the theory according to which the hetsiwa and

the wabu represent, as it were, immobilized

clappers, must be put forward with extreme prudence.

Yet the existence of similar

conceptions among the ancient Egyptians gives it a

certain credibility. I am well aware that Plutarch's

evidence is often suspect. I therefore make no claim

to be restating authentic beliefs since, as far as I

am concerned, it is of scant importance whether the

imagery to which I am about to refer originated

among reliable Egyptian sages, among a handful of

Plutarch's informants, or in Plutarch's own mind.

In my view, the only point worthy of

attention is that, after I had noted on several

occasions that the intellectual processes evidenced

in Plutarch's work presented a curious similarity to

those I was deducing from South American myths, and

that, consequently, in spite of the time gap and

geographical distance, I had to admit that in both

instances human minds had worked in the same way, a

new convergence should emerge in connection with a

hypothesis I would not have dared to put forward,

had it not made the comparison justifieable. Here

then is Plutarch's text:

Moreover, Manethus says that the

Egyptians have a mythical tradition in regard to

Jupiter, that because his legs were grown together

he was not able to walk and so for shame tarried in

the wilderness; but Isis, by severing and separating

those parts of his body, provided him with means of

rapid progress.

This fable teaches by its legend that

the mind and reason of the god, fixed amid the

unseen and invisible, advanced to generation by

reason of motion.

The sistrum, a metallic rattle, also

makes it clear that all things in existence need to

be shaken, or rattled about, and never to cease from

motion but, as it were, to be waked up and agitated

when they grow drowsy and torpid.

They say that they avert and repel

Typhon by means of the sistrum, indicating thereby

that when destruction constricts and checks Nature,

generation releases and arouses it by means of

motion (Plutarch's Moralia. Isis and Osiris,

376).

Is it not extraordinary that the

Karaja, whose magical practices and the problems

they raise have led us to Plutarch, should have

evolved a story completely symmetrical with his?

They say that Kanaschiwué,

their demiurge, had to have his arms and legs tied

to prevent him from destroying the earth by floods

and other disasters, as he would have done had his

movements been unrestricted (Baldus 5, p. 29).17

17 In the same way, it

would also be appropriate to re-examine the famous

episode of Aristeus (Virgil, Georgics, IV) in

which Proteus (who corresponds to Plutarch's Typhon)

has to be bound hand and foot during the dry season:

'Iam rapidus torrens sitientis Sirius Indos',

in order to make him consent to show the shepherd

how to find honey again, after it had been lost as a

result of the disappearance of Eurydice, the

mistress, if not of honey like the heroine of M233-M234,

undeniably mistress of the honeymoon! Eurydice, who

is swallowed by a monstous sea-serpent (ibid.,

v. 459), is an inversion of the heroine of M326a

who was born from a sea-serpent and who rejected a

honeymoon, in the days when animals had the gift of

speech, and therefore would not have had any use for

an Orpheus.

In spite

of its obscurity, the Greek text introduces a clear

contrast between, on the one hand silence and

immobility symbolized by two limbs normally separate

yet welded together, and on the other movement and

noise, symbolized by the sistrum.

As in

South America, unlike the first term, only the

second term is a musical instrument. As in South

America also, this musical instrument (or its

opposite) is used to 'divert or drive away' a

natural force (or it is used to attract it for

criminal purposes): in one instance, it is Typhon,

that is, Seth; in the other, the tapir or snake as

seducers, the snake-rainbow associated with rain,

rain itself or the chthonian spirits." (From Honey

to Ashes)

Hercules too was tied

up and killed at the time of summer solstice, we

remember:

|

... Hercules first appears in legend as

a pastoral sacred king and, perhaps

because shepherds welcome the birth of

twin lambs, is a twin himself.

His characteristics and history can be

deduced from a mass of legends,

folk-customs and megalithic monuments.

He is the rain-maker of his tribe and a

sort of human thunder-storm. Legends

connect him with Libya and the Atlas

Mountains; he may well have originated

thereabouts in Palaeolithic times. The

priests of Egyptian Thebes, who called

him 'Shu', dated his origin as '17,000

years before the reign of King Amasis'.

He carries an oak-club, because the oak

provides his beasts and his people with

mast and because it attracts lightning

more than any other tree. His symbols

are the acorn; the rock-dove, which

nests in oaks as well as in clefts of

rocks; the mistletoe, or Loranthus;

and the serpent. All these are sexual

emblems.

The dove was sacred to the Love-goddess

of Greece and Syria; the serpent was the

most ancient of phallic totem-beasts;

the cupped acorn stood for the glans

penis in both Greek and Latin; the

mistletoe was an all-heal and its names

viscus (Latin) and ixias

(Greek) are connected with vis

and ischus (strength) - probably

because of the spermal viscosity of its

berries, sperm being the vehicle of

life.

This Hercules is male leader of all

orgiastic rites and has twelve archer

companions, including his spear-armed

twin, who is his tanist or

deputy. He performs an annual green-wood

marriage with a queen of the woods, a

sort of Maid Marian. He is a mighty

hunter and makes rain, when it is

needed, by rattling an oak-club

thunderously in a hollow oak and

stirring a pool with an oak branch -

alternatively, by rattling pebbles

inside a sacred colocinth-gourd or,

later, by rolling black meteoric stones

inside a wooden chest - and so

attracting thunderstorms by sympathetic

magic ... |

|

... The manner of his death can be

reconstructed from a variety of legends,

folk-customs and other religious

survivals. At mid-summer, at the end of

a half-year reign, Hercules is made

drunk with mead and led into the middle

of a circle of twelve stones arranged

around an oak, in front of which stands

an altar-stone; the oak has been lopped

until it is T-shaped. He is bound to it

with willow thongs in the 'five-fold

bond' which joins wrists, neck, and

ankles together, beaten by his comrades

till he faints, then flayed, blinded,

castrated, impaled with a mistletoe

stake, and finally hacked into joints on

the altar-stone. His blood is caught in

a basin and used for sprinkling the

whole tribe to make them vigorous and

fruitful. The joints are roasted at twin

fires of oak-loppings, kindled with

sacred fire preserved from a

lightning-blasted oak or made by

twirling an alder- or cornel-wood

fire-drill in an oak log.

The trunk is then uprooted and split

into faggots which are added to the

flames. The twelve merry-men rush in a

wild figure-of-eight dance around the

fires, singing ecstatically and tearing

at the flesh with their teeth. The

bloody remains are burnt in the fire,

all except the genitals and the head.

These are put into an alder-wood boat

and floated down the river to an islet;

though the head is sometimes cured with

smoke and preserved for oracular use.

His tanist succeeds him and reigns for

the remainder of the year, when he is

sacrificially killed by a new Hercules

... |

We

understand more and more of the myths. I guess

the Easter Island version of 'Typhon' /

'Hercules' etc may be the spring god Tagaroa

Uri (who causes the greenery to spread out

and life to grow). Though it is surely King

Oto Uta who is the generator, who wins the

battle against the old year. Let us quickly

recapitulate the story on Hawaii:

|

...

Power reveals and defines itself as the

rupture of the people's own moral order,

precisely as the greatest of crimes

against kinship: fraticide, parricide,

the union of mother and son, father and

daughter, or brother and sister ...

...

power is not represented here as an

intrinsic social condition. It is

usurpation, in the double sense of a

forceful seizure of sovereignity and a

sovereign denial of the prevailing moral

order. Rather than a normal succession,

usurpation itself is the principle of

legitimacy. Hocart shows that the

coronation rituals of the king or

paramount chief celebrate a victory over

his predecessor. If he has not actually

sacrificed the late ruler, the heir to

the Hawaiian kingship, or some one of

his henchmen, is suspected of having

poisoned him.

There

follows the scene of ritual chaos...

when the world dissolves or is in

significant respects inverted, until the

new king returns to reinstate the tabus,

i.e., the social order. Such mythical

exploits and social disruptions are

common to the beginnings of dynasties

and to successive investitures of divine

kings.

We can

summarily interpret the significance

something like this: to be able to put

the society in order, the kin must first

reproduce an original disorder. Having

committed the monstrous acts against

society, proving he is stronger than it,

the ruler proceeds to bring system out

of chaos. Recapitulating the initial

constitution of social life, the

accession of the king is thus a

recreation of the universe. The king

makes his advent as a god. The symbolism

of the installation rituals is

cosmological ...

...

The rationalization of power is not at

issue so much as the representation of a

general scheme of social life: a total

'structure of reproduction', including

the complementary and antithetical

relations between king and people, god

and man, male and female, foreign and

native, war and peace, heavens and earth

... |

|

...

The divine first appears abstractly, as

generative-spirit-in-itself. Only after

seven epochs of the po, the long

night of the world's self-generation,

are the gods as such born - as siblings

to mankind. God and man appear together,

and in fraternal strife over the means

of their reproduction: their own older

sister.

Begun

in the eighth epoch of creation, this

struggle makes the transition to the

succeeding ages of the ao, the

'day' or world known to man. Indeed the

struggle is presented as the condition

of the possibility of human life in a

world in which the life-giving powers

are divine. The end of the eighth chant

thus celebrates a victory: 'Man spread

about now, man was here now; / It was

day [ao].'

And

this victory gained over the god is

again analogous to the triumph achieved

annually over Lono at the New

Year, which effects the seasonal

transition, as Hawaiians note, from the

time of long nights (po) to the

time of long days (ao). The older

sister of god and man, La'ila'i,

is the firstborn to all the eras of

previous creation. By Hawaiian theory,

as firstborn La'ila'i is the

legitimate heir to creation; while as

woman she is uniquely able to transform

divine into human life.

The

issue in her brothers' struggle to

possess her is accordingly cosmological

in scope and political in form.

Described in certain genealogies as

twins, the first two brothers are named

simply in the chant as 'Ki'i, a

man' and 'Kane, a god'. But since

Ki'i means 'image' and Kane

means 'man', everything has already been

said: the statuses of god and man are

reversed by La'ila'i's actions.

She 'sits sideways', meaning she takes a

second husband, Ki'i, and her

children by the man Ki'i are born

before her children by the god Kane...

...

In the succeeding generations, the

victory of the human line is secured by

the repeated marriages of the sons of

men to the daughters of gods, to the

extent that the descent of the divine

Kane is totally absorbed by the

heirs of Ki'i ... |

Jupiter 'tarried in the wilderness' because his

'legs were grown together', just as the statue

of Oto Uta was left behind. The 'legs' in

question we saw already in the statue of

Pachamama:

|

... Notice that the

right leg (left as seen from the

statue) is 'summer' and the left leg

'winter'. In ancient times they

could manage with two seasons. And

right step first is a rule north of

the equator only. The word 'summer'

is related to the Sanskrit word 'sáma'

= half-year ... |

Let us

now return to Hawaii and what Sahlins describes

in his Islands of History:

"... In

the Saturnalia, the Lupercalia, their carnival

successors and analogous annual festivals of

traditional kingdoms elsewhere, a further

permutation of the original structure appears. At

this time of cosmic and social rebirth, celeritas

and gravitas exchange places: the people

become the party of disorder, and the celebration of

their community is a so-called ritual of rebellion."

celerity ... swiftness ... L. celeritās

... prob. rel. to Gr. kéllein drive, kélēs

runner ... (English Etymology)

Kings move

slowly, while their servants should run. Remember

Aa1-3--4:

"... At

the Hawaiian annual [annular, annullation] ceremony

of this type, the Makahiki ('Year), the lost

god cum legendary king returns to take possession of

the land.

Circulating the island to collect the offerings of

the people, he leaves in his train scenes of mock

battle and popular celebration.

At the

end of the god's progress, the Hawaiians perform a

version of the Fijian installation ceremonies. The

reigning king comes in from the sea to be met by

attendants of the returned popular god hurling

spears, one of which is caused to symbolically reach

its mark.

Thus

killed by the god, the king enters the temple to

sacrifice to him and welcome him to 'the land of

us-two'.

Yet the

death of the king is also the moment of his

reascension, and in the end it is the god who is

sacrificed. Just as the povisional king of carnival

must eventually suffer execution, the image of the

returned god is soon after dismantled, bound, and

hidden away - a rite watched over by the ceremonial

double (or human god) of the king, one of whose

titles is 'Death is Near'.

Thereupon, the real usurper, the constituted king,

resumes his normal business of human sacrifice."

The mock battle with

clappers, upheaval, turning everything upside down (to

induce the sun return from his 'sleep' in

the middle of the 'water') could be symbolized with

two wooden 'limbs' crossed as in GD76 (hahe):

| Hahe

Hahehahe. To

congregate, to gather (of people,

animals, things). Hahei, to

encircle, to surround. Ku hahei á te

tagata i ruga i te umu, he vari, the

people have placed themselves around the

oven, forming a circle. Ana ká i te

umu, he hahei hai rito i raro, when

you cook food (lit.: light the oven) you

cover it all around with banana leaves

at the bottom. Vanaga.

M.

Whawhe,

to come or go round. Cf. hawhe,

to go or come round; awhe, to

pass round or behind; takaawhe,

circuitous. 2. To put round. 3. To be

blown away by the wind. Te aute tč

whawhea - Prov. 4. To grasp, to

seize. Cf. wha, to lay hold of;

to handle. 5. To save, as a defeated

person on a battle-field. Text Centre. |

The executive

on earth, i.e. the king (GD63, ariki), must

induce his 'runners' to 'move' by the power of his

'sword' (without doubt a 'wooden' one); he must be prepared

to 'make battle' (e.g. by way of human sacrifice):

That is one reason for

him having a base on crossed sticks. The sticks are a kind

of socialized 'instruments of darkness'.

If we remove the king

from his position at the top of the 'instruments of

darkness' we once again have GD76 (hahe),

where people congregate (hahehahe) and seize

(Ma.: whahe) the power. This probably is the

6th station of the kuhane, Te Piringa

Aniwa:

... The

cult place of Vinapu is located between the

fifth and sixth segment of the dream voyage of

Hau Maka. These segments, named 'Te Kioe Uri'

(inland from Vinapu) and 'Te Piringa Aniva'

(near Hanga Pau Kura) flank Vinapu

from both the west and the east.

The

decoded meaning of the names 'the dark rat' (i.e.,

the island king as the recipient of gifts) and 'the

gathering place of the island population' (for the

purpose of presenting the island king with gifts)

links them with the month 'Maro' which is

June.

Thus,

the last month of the Easter Island year is twice

mentioned with Vinapu. Also, June is the

month of the summer [a misprint for winter]

solstice, which again points to the possibility that

the Vinapu complex was used for astronomical

purposes ...

|

Piri 1. To

join (vi, vt); to meet someone on the

road; piriga, meeting, gathering.

2. To choke: he-piri te gao. 3.

Ka-piri, ka piri, exclamation:

'So many!' Ka-piri, kapiri te pipi,

so many shellfish! Also used to

welcome visitors: ka-piri, ka-piri!

4. Ai-ka-piri ta'a me'e ma'a,

expression used to someone from whom one

hopes to receive some news, like saying

'let's hear what news you bring'. 5.

Kai piri, kai piri, exclamation

expressing: 'such a thing had never

happened to me before'. Kai piri, kai

piri, ia anirá i-piri-mai-ai te me'e

rakerake, such a bad thing had never

happened to me before!

Piripiri,

a slug found on the coast, blackish,

which secretes a sticky liquid.

Piriu,

a tattoo made on the back of the hand.

Vanaga.

1. With, and. 2. A

shock, blow. 3. To stick close to, to

apply oneself, starch; pipiri, to

stick, glue, gum; hakapiri,

plaster, to solder; hakapipiri,

to glue, to gum, to coat, to fasten with

a seal; hakapipirihaga, glue. 4.

To frequent, to join, to meet, to

interview, to contribute, to unite, to

be associated, neighboring; piri mai,

to come, to assamble, a company, in a

body, two together, in mass,

indistinctly; piri ohorua, a

couple; piri putuputu, to

frequent; piri mai piri atu,

sodomy; piri iho, to be addicted

to; pipiri, to catch; hakapiri,

to join together, aggregate, adjust,

apply, associate, enqualize, graft,

vise, join, league, patch, unite.

Piria;

tagata piria, traitor.

Piriaro

(piri 3 - aro), singlet,

undershirt.

Pirihaga, to

ally, affinity, league.

Piripou

(piri 3 - pou), trousers.

Piriukona,

tattooing on the hands. Churchill. |

|

Niva

Nivaniva, madman,

idiot. Vanaga.

Nivaniva, absurd,

stupidity, bungler, delirium,

madness, to err, to wander in

mind, folly, foolish, heedless,

frenzied, imbecile, senseless,

odd, inconsistent, simple, dupe,

stupid, flighty (nevaneva);

nivaniva o te mata,

lethargy.

Hakanivaniva, queer,

bewitched, stupefied, to tell

lies. PS Ta.:

nivaniva,

neneva, foolish,

stupid, mad. Sa.:

niniva, giddy, dizzy.

Churchill. |

I think there is a

reference in Te Piringa Aniwa to the 'madman'

(nivaniva) - i.e. the anarchy of the gathered

people, the mob, who is temporarily (during the

period of the 3 black nights of the 'slug',

piripiri) are taking over the rule from the

king.

|