|

TRANSLATIONS

It is time to return to the glyph dictionary. A final note from Gates, though:

"... for the most important of all the days, the first, Imix, we find the corresponding forms Imox, Imos in Quiché and Tzeltal, defined in the earliest Quiché dictionaries as meaning espadarte, swordfish. We find Mox in Pokonchi, but with no early definition."

The 'water dragon' is a mythical beast, and cannot be identified as any special species in nature. It is a swordfish, it is a lizard, it is a shark, it is a macaw. It might even be a dragon, because around the North Pole such a constellation is winding.

I have updated the first page about haga rave, and distributed its contents onto three pages:

| A few preliminary remarks and imaginations: 1. The haga rave glyph type does not show a picture of a 'bay', instead it appears to be an illustration of a bent branch.

Sometimes the implication may be not only bent but rather 'broken' as in Pa5-40:

"The Polynesians mingle the time-indications based on the position of the sun with others which are derived from the life of men and nature. We are told that the Hawaiian day was divided into three general parts, 1, breaking the shadows, 2, the plain, full day, 3, the decline of the day... " (Nilsson)

Pa5-40 could be an allusion to daybreak ('breaking the shadows').

A bent branch can symbolize 'change'. The 'curved' was according to the Pythagorean school a 'female' trait:

“Freeman describres the dualistic cosmology of the Pythagorean school (-5th century), embodied in a table of ten pairs of opposites. On one side there was the limited, the odd, the one, the right, the male, the good, motion, light, square and straight. On the other side there was the unlimited, the even, the many, the left, the female, the bad, rest, darkness, oblong and curved.” (Needham 3)

From this it is clear that there is a high probability for 'curved' to also imply 'darkness' in the minds of the Easter Islanders. This is one reason (among others) to interpret 'breaking the shadows' as going from the female night to the male day.

Night is divided in two parts by midnight. Noon has not the same power of division, because it is the same day before and after noon. Day is male, night is female.

The haga rave glyph type maybe should be understood not only as the object 'bent branch' but also - and primarily - as a symbol for the flexible 'female'. The bent branch is soft and pliant, otherwise it could not be bent at all - under stress it would break to pieces. |

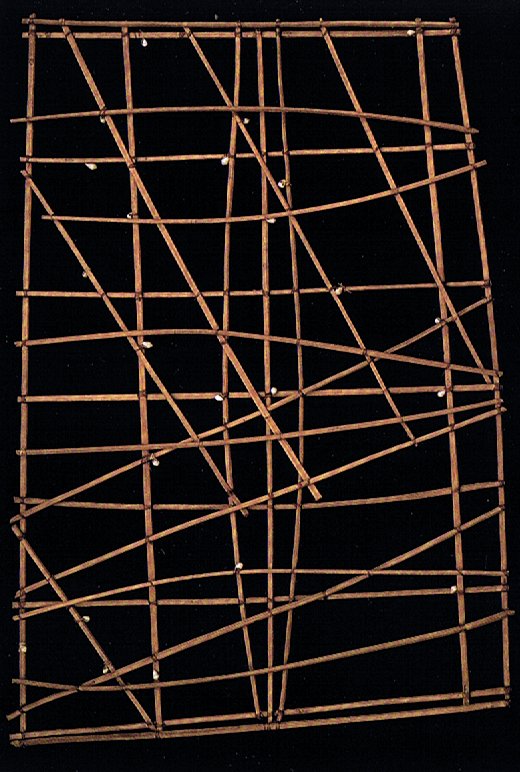

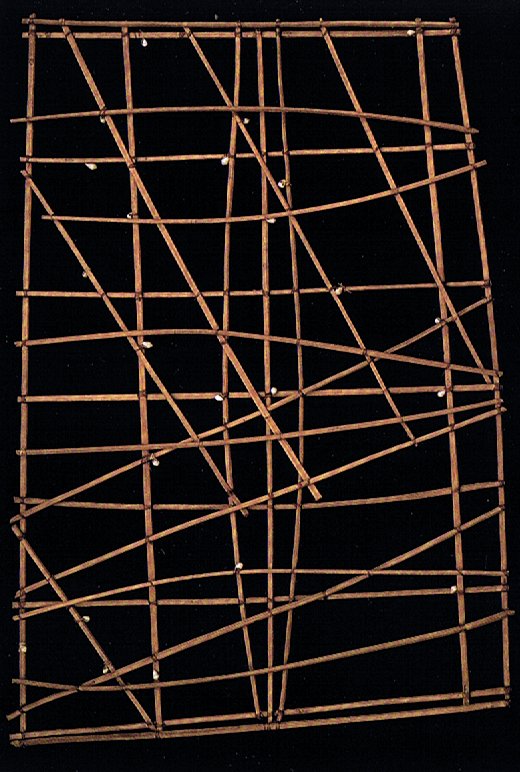

| 2. Sailing charts, rib charts, should be mentioned here. An example from the Marshall Islands (ref. D'Alleva) was made from 'wood, shells, and vegetable fibres':

"In order to traverse these great distances, the Lapita must have been skilled navigators and sailors, just like their descendants, the Polynesians. Navigational techniques still in use in Micronesia may provide insight into the ancient traditions of Lapita and Polynesian seafaring. In traditional navigational schools on Puluwat in the Caroline Islands, students learn how to sail outrigger canoes. As Puluwat sailors conceptualize a voyage between two islands, it is the islands that move rather than the canoe: the starting point recedes as the destination approaches.

Puluwat map the skies by the constellations and the ocean by its distinguishing features; islands, reefs, swells, areas of rough water. Similarly, a Marshall Islands stick chart uses shells to indicate specific islands and patterns of sticks lashed together to illustrate currents and common wave formations in a form that is both supremely functional and aesthetically appealing." (D'Alleva)

Before we condemn the Polynesians for their ignorance when thinking that the canoe is standing still while the island in front is moving towards them, we should consider our own similar behaviour: We say that the sun and the stars move across the sky from east to west, when we instead ought to say that it is the earth which is turning.

Reality is hard to face. Therefore we prefer to say the sky is moving - not we down on earth. If we often used to travel long distances by canoe we would therefore (presumably) say that the water is moving - not we (in the canoe). |

There may be a reason for Ha6-6 (and similar glyphs) to appear at noon (or midsummer), because the 'tree' is at its highest there. We remeber the contest when the Jaguar lost his first (good) eyes while juggling with them:

... the jaguar invited the anteater to a juggling contest, using their eyes removed from the sockets: the anteater's eyes fell back into place, but the jaguar's remained hanging at the top of a tree ...

And then, more to the point because it happened on Easter Island, Ure Honu hung up the head of Hotu Matua high under his roof:

... He took the very large skull, which he had found at the head of the banana plantation, and hung it up in the new house. He tied it up in the framework of the roof (hahanga) and left it hanging there ...

I ought to add something to try to explain why there is a fishhook at noon. But then I must also be able to explain why these glyphs appear during the 2nd half of the week:

|

Here (in Ab6-42--57), the meaning presumably is to indicate the 2nd half - the part which comes beyond the middle.

We conclude that the other variant of hakaturou (in Sunday-Wednesday) - which has a rather straight 'neck' - probably refers to the 1st half.

Although Sunday is special, which is indicated e.g. by a 'head' with an upwards pointing 'mouth' drawn with two straight lines.

|

The straight hakaturou glyphs possibly are 'sky proppers' pushing the 'roof' higher and higher up to the 'noon' of the week, but that does not make the fishhook type more understandable, rather the opposite.

In Thursday and Friday the immediately following hipu (calabash etc) maybe can give us a lead:

|

Hipu

Calabash, shell, cup, jug, goblet, pot,

plate, vase, bowl, any such receptacle; hipu hiva, melon, bottle;

hipu takatore, vessel; hipu unuvai, drinking glass.

P Mgv.: ipu, calabash, gourd for carrying liquids. Mq.: ipu,

all sorts of small vases, shell, bowl, receptacle, coconut shell. Ta.:

ipu, calabash, cup, receptacle. Churchill. |

The first half of the week is obviously male in character (straight standing up and pushing), while the second half is female (receptacle and fruitful). The 'beak' in the 2nd half of the week is different, which I have commented upon:

The double-headed hakaturou glyph Bb6-17 should be compared with another such glyph, Eb8-25:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Eb8-13 |

Eb8-14 |

Eb8-15 |

Eb8-16 |

Eb8-17 |

Eb8-18 |

Eb8-19 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Eb8-20 |

Eb8-21 |

Eb8-22 |

Eb8-23 |

Eb8-24 |

Eb8-25 |

Eb8-26 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Eb8-27 |

Eb8-28 |

Eb8-29 |

Eb8-30 |

Eb8-31 |

Eb8-32 |

Eb8-33 |

The two 'beaks' in Eb8-25 are differently drawn, the one at right looking similar to those in Monday-Wednesday and the one at left similar to the 'beaks' in Thursday-Saturday:

|

I said nothing about 'male' contra 'female'. If at 'noon' there is a 'change of sexes' (meaning the 'pusher' is decapitated and his 'wife' taking over the 'government'), the 'beak' must change form.

The haga rave glyph type is female, it illustrates not only a flexible bent branch but also a receptacle in its outline.

I have also referred to moai meaning 'promising young lads':

| "... It was a mark of distinction for a grown son or a brave young man to be referred to as a 'rooster' (moa).

One of the Rongorongo tablets and a petroglyph (Barthel 1962) indicate that the group of explorers of the immigrant cycle were known as 'roosters'. The same figurative meaning is found in a fragment of the Metoro chants:

|

e moa te erueru |

Oh rooster, who scratches diligently! |

|

e moa te kapakapa |

Oh rooster, who beats his wings! |

|

e moa te herehua |

Oh rooster, who ties up the fruit! |

|

ka hora |

Spread out! |

|

ka tetea |

Have many descendants! |

|

(Barthel 1958:186) |

|

The deeper meaning of this passage can be discovered by comparing it with the 'great old words' (Barthel 1959a:168).

The 'one who beats his wings' refers to the best person, and the 'one who ties up the fruit' refers to the richest. The 'one who scratches diligently' must be a person who is industrious, so that we can interpret the praise of a promising young man." (Barthel 2) |

I now understand why Metoro stopped with his 'moa' at midsummer - the moa he thought of were male.

Contemplating the hakaturou glyphs in the 2nd part of the week, one cannot but think about e moe te herehua, the one who ties up the fruit. But he occurs too early, and ka tetea is located more accurately in the enumeration:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Aa1-5 |

Aa1-6 |

Aa1-7 |

Aa1-8 |

Aa1-9 |

Aa1-10 |

Aa1-11 |

Aa1-12 |

| ko te moa |

e noho ana ki te moa |

e moa te erueru |

e moa te kapakapa |

e moa te herehua |

ka hora ka tetea |

ihe kuukuu ma te maro |

ki te henua |

The word haga (bay) does not obviously connect, I think, to the picture I have tried to paint. But hâgai and hagahuru are more close:

| Hagahuru Ten (agahuru, hagauru). P Mq.: onohuú, okohuú, id. Ta.: ahuru. id. Churchill.

The Maori recognized two main divisions of the year: winter or takurua, a name for Sirius which then shone as morning star, and summer, raumati or o-rongo-nui, 'of the great Rongo', god of agriculture. They occasionally recognized spring as the digging season koanga, from ko, the digging stick or spade. The autumn or harvest season was usually spoken of as ngahuru, 'tenth' (month), although it was considered to include also the last two months of the year. Mahuru was the personification of spring. Makemson. |

| Hâgai To feed. Poki hâgai, adopted child. Vanaga.

To feed, to nourish, forster-parent (agai); hagai ei u, to suckle. P Pau.: fagai, to feed, to maintain, to support. Mgv.: agai, to nurse, to nurture, to give food to, an adoptive or foster father; akaagai, to feed. Mq.: hakai, to feed. Ta.: faaai, to nourish, a foster-parent. Churchill. |

The 10th glyph in the first line on side a of Tahua illustrates a point of turning around. A moon sign (descending) appears at the elbow. Normally en face means that we can see two 'sun eyes', but here the old one (left from us seen) has gone. The sign of tagata (fully grown) has lost the old 'eye'.

The descending moon sign should imply Aa1-10 is standing at an Omotohi position, where the 'suckling' (omo) season (growing) is over and the fruit (hua) is cut down (tohi):

According to the words of Metoro he presumably meant we should understand that the time of spreading out (hora) is over:

| Hora Ancient name of summer (toga-hora, winter summer). Vanaga.

1. In haste (horahorau). 2. Summer, April; hora nui, March; vaha hora, spring. 3. 'Hour', 'watch'. 4. Pau.: hora, salted, briny. Ta.: horahora, bitter. Mq.: hoáhoá, id. 5. Ta.: hora, Tephrosia piscatoria, to poison fish therewith. Ha.: hola, to poison fish. Churchill.

Horahora, to spread, unfold, extend, to heave to; hohora, to come into leaf. P Pau.: hohora, to unfold, to unroll; horahora, to spread out, to unwrap. Mgv.: hohora, to spread out clothes as a carpet; mahora, to stretch out (from the smallest extension to the greatest), Mq.: hohoá, to display, to spread out, to unroll. Ta.: hohora, to open, to display; hora, to extend the hand in giving it. Churchill. |

| Tetea To have many descendants. Vanaga. |

Was the great 'a.m. fish' poisoned (Hawaiian hola)? I have always found the French word poisson (fish) strangely similar to poison. On April 1 the French say 'donner quelqu'un une poisson', a very strange expression meaning 'give somebody a fish'. The 'fish' arrives in spring and dies at midsummer, I think.

The 2nd half of the week, then, should correspond to the time when growth no longer occurs. The 'dead skulls' are hung up to dry under the roof. A 'calabash' (hipu) should be dry to become useful.

Now I dare suggest a meaning for the fishhook sign. I revise the page into:

|

3. The

primary meaning of haga rave glyphs may be

change.

Darkness is a power contrary to light. In spring (or at dawn) the

light is strong and winning over darkness, in autumn (or dusk) the

light is weaker. At the solstices the powers of light and darkness

weigh equal, but there the most important changes occur, slowly at

first and then accelerating.

In the Hawaiian language the word moai means

'bending over, arching like a tree', and at some point in life

('zenith') people indeed start to bend over, a process which is

difficult to see at the beginning but very clear later in life.

Their backs are no longer straight and their heads are leaning

forward, starting to hang down like ripe fruits. Could, maybe, the

'fishhook' variant of hakaturou in for instance Ha6-6

indicate this idea? Hardly, the 'head' is definitely not starting to

hang down:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Ha6-1 |

Ha6-2 |

Ha6-3 |

Ha6-4 |

Ha6-5 |

Ha6-6 |

Ha6-7 |

Ha6-8 |

A moai statue stands high, as if at zenith,

helping to keep the sky up ('sky propper'). Combining the 'sky

propper' with haga rave can, though, be done by fusing

together the two glyph types:

|

|

"Night came, midnight

came, and Tuu Maheke said to his brother, the last-born: 'You

go and sleep. It is up to me to watch over the father.' (He said)

the same to the second, the third, and the last.

When all had left, when

all the brothers were asleep, Tuu Maheke came and cut off the

head of Hotu A Matua.

Then he covered everything with soil. He hid (the head), took it,

and went up. When he was inland, he put (the head) down at Te

Avaava Maea. Another day dawned, and the men saw a dense swarm

of flies pour forth and spread out like a whirlwind (ure tiatia

moana) until it disappeared into the sky.

Tuu Maheke

understood. He went up and took the head, which was already stinking

in the hole in which it had been hidden. He took it and washed it

with fresh water. When it was clean, he took it and hid it anew.

Another day came, and

again Tuu Maheke came and saw that it was completely dried

out (pakapaka). He took it, went away, and washed it with

fresh water until (the head) was completely clean. Then he took it

and painted it yellow (he pua hai pua renga) and wound a

strip of barkcloth (nua) around it.

He took it and hid it

in the hole of a stone that was exactly the size of the head. He put

it there, closed up the stone (from the outside), and left it there.

There it stayed." (Barthel 2) |

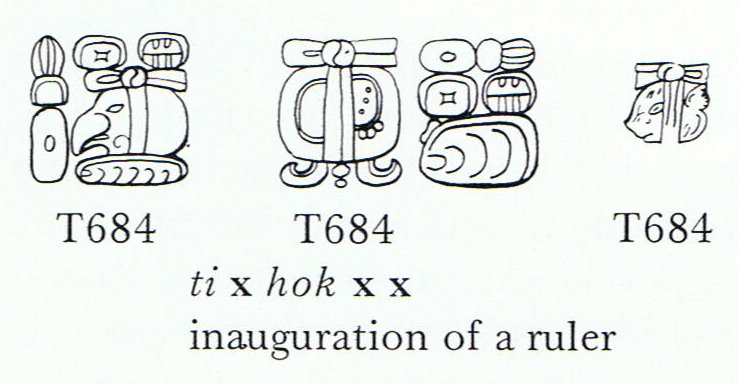

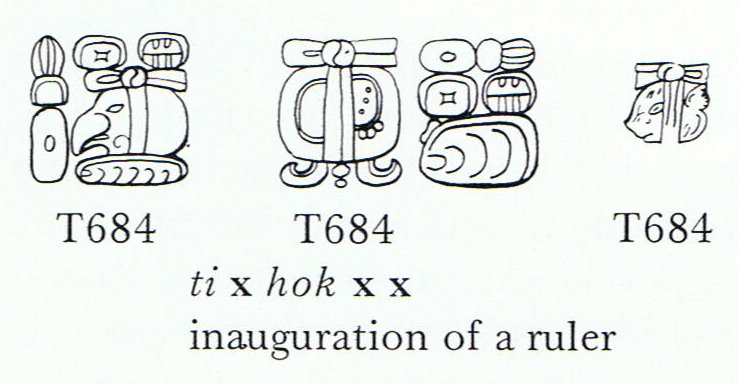

Did Tuu Maheke took on his

father's role by tying the strip of cloth around the head? The Maya indians

would immediately have recognized the sign of the 'toothache' glyph:

|

| 'toothache glyph' |

|