|

TRANSLATIONS

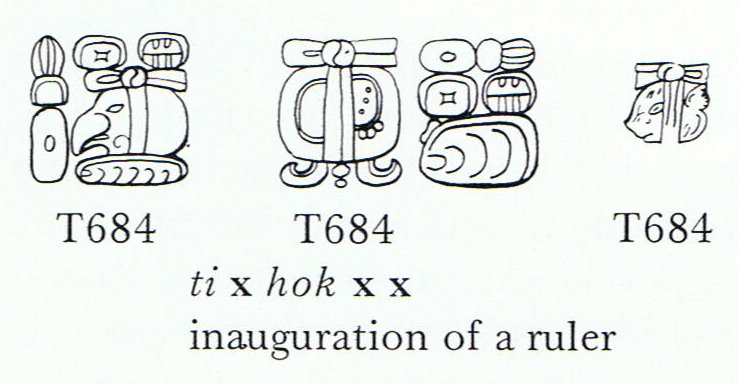

A new phase has been reached in my efforts to understand the rongorongo texts. The balance tipped over when I recognized the 'toothache' glyph in how Tuu Maheke took care of his fathers skull. No longer can I regard the Mayan system of thought as possibly far away related to the Easter Island system of thought. The connections are too many and show, I think, a much closer connection than I had imagined possible. Did Barthel realize this too? Why and when did he turn to studying the Maya glyphs? Even if the Easter Island system of thought is a close relative of the Mayan system of thought it does not necessarily mean the rongorongo writers shared the same system of thought. But it seems very probable that they did. The change in my view is a dangerous phenomenon. It will tend to increase my credulity. For instance, I am already toying with the idea that the name Tuu Maheke could be related to ti x hok xx:

The first 'x' could be a parallel to ma in Maheke. The inauguration of a ruler presumably refers to what happens at New Year, and heke (octopus) may refer to an 8-fold division of the sky around the pole. The octopus is not a creature of the sky, but on Easter Island the North Star is below the horizon in the north, i.e. in a way down in the sea. Heke has other meanings too, several of them - I think - relevant in our discussion:

Tuu Maheke did not overthrow (hakaheke) his father, but he succeded him. And he cut (Hawaiian helehele) his head and buried it. It then should become his role to deflower (hakaheke) Blood Moon late in the year. Most interesting, though, is the Paumotuan hekeheke (presumably an intensified heke) meaning elephantiasis - suggesting 'pau' as for instance in va'e pau (clubfoot):

And then, another imaginative idea of mine concurs: .. almost if not quite the most important deities in the Maya ritual were the Four Chacs, the Pauah-tun, ruling the four quarters and colors. It is their cult that goes through the chants from first to last, with the colors and offerings, and with Itzamná and his consort Ixchel as the great superior, beneficient deities. Both the Chacs and Itzamná ruled the Quarters, He through them; He was the God, they the Guardians, and either could be called Red Lord, White Lord, etc. In most mythologies the East and North are the sacred quarters; in one of the chants Itzamná is called U yum ki chac ahau Itzamna, 'Father of the Sun, Great Lord Itzamná', repeating one of the traditions which represents Kin-ich-ahau as the son of Itzamná. So that we not only have 'the Lord Sun, the East', on the authority both of the glyphs and the texts, but also (on the strength of our glyph 71.1 or 75.1) 'The Lord' among the Chacs, for the North - and of course its Star ... Pauah-tun is a word which obviously has tun (the 360-day year) at its end. The beginning will then be pauah, which I do not know the meaning of. But I can speculate: Pauah-tun are the Four Chacs, Gates says, and therefore pauah possibly is related to 4. Towards the end of the 4th quarter time is running out (for the old year) - pau in Polynesian:

I can go on. The words of Metoro relating to the phases of the day are still rather puzzling.

He said hoki twice (at 28 and 32 - female numbers implying 'spreading out') presumably to indicate how death is followd by next generation, I imagine.

The word hoko (to jump etc, possibly referring to the jump from one generation to the next, as for instance - presumably - is alluded to in the story about how the people at the House of Cockroaches were taking the stones from the earth-oven and throwing out the ends of burning wood whereupon Tu'u ko ihu took two of them and carved them into moai kavakava.

In hokohuki the primary word is hoko (according to Polyensian custom), and huki has a determinative function:

Much food for thought is buried in huki, and I have to leave this train of thoughts for the moment. But my intuition tells me there is a connection between the hokohuki of Metoro and the haga rave glyph type:

|