|

TRANSLATIONS

Gates is trying hard to integrate the Maize God (Yum Kaax) into the North Star perspective:

"There is only one solution that will satisfy the above usage of glyphs 71 to 76. The banded headdress in itself must be a sign of Lordship, as in Yum Kaax, Lord of the Cornfields." I do not agree. There must be more to it. The sign of corn in 18 Cumhu certainly connects the month to the Cornfields. Anciently signs were not arbitrary:

And in Aa1-14 a similar concept of the dark fruitful earth presumably is documented:

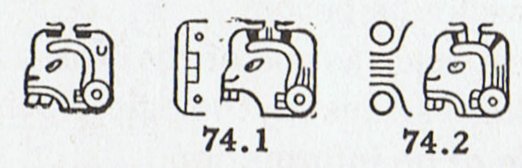

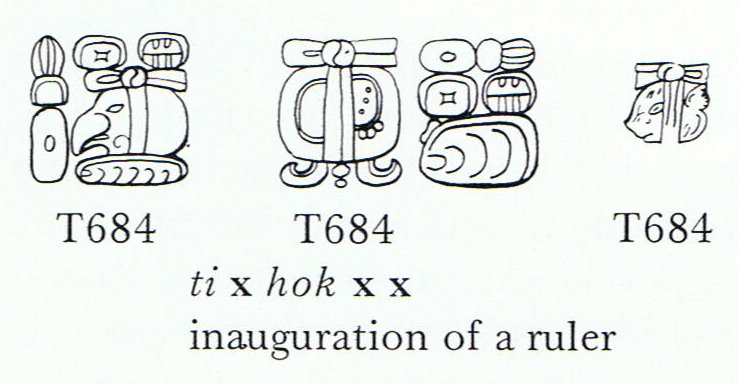

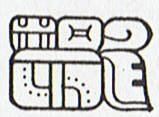

Aa1-13 reminds me about how '20' (equally valid as 13 to signify 'end') is 'imprisoned', presumably in Mother Earth: ... By the way, I just happened to read in Kelley: Cyrus Thomas ... drew attention to a 'representation of an idol head in a vessel covered with a screen or basket'. Above it was the glyph also found for 'twenty', Yucatec kal, and he pointed out that kal also 'signifies to imprison or inclose which is certainly appropriate to what we seen the figure'. It may be pointed out that Tzeltal shows a comparable semantic parallelism, for tab is both 'twenty' and 'tie'. However, 'inclose' is the more relevant term here, and Yucatec kal seems a preferable reading. It may be pointed out that the 'twenty' glyph appears at Yaxchilan as an apparent epithet of the ruler Bird Jaguar. Yucatec kal is cognate with Huaxtec ts'ale 'king' and with Quiche q'alel, a title, the head of a group, and is probably included in Yucatec ixikal 'señora principal' ('noble lady'). I would, therefore, translate it 'the great ruler'. The idol head in the vessel, I think, represents the ruler at the time of conjunction. He is caught ... "... Proskouriakoff (1960, pp. 456-457 and elsewhere) has shown that certain dates which seem to be associated with the beginnings of reigns are accompanied by the 'toothache glyph' [T684] with a wide variety of infixes, including the kal glyph.

Cordan (1963a, pp. 45, 49) suggests the 'toothache glyph' is hok + kal (Ticul dictionary, hokal, 'bound together'; Tzotzil hokol, assimilated form, 'hung up'). More recently, Barthel (1968a, p. 136) has pointed out that hok is found as a Yucatec root meaning 'to put in office'. This makes it virtually certain that the reading hok is correct. If the offering scenes are connected with divination, it may be relevant that Tzeltal -jok'iy is 'preguntar' ('to ask a question')." (Kelley) At new year 'the dice are thrown', it is a 'Chamber of Hazard'. The 'head' is in the dark, in the 'Palace Chapel'. The new life depends on the 'fruitful field'. The 'head' of the old one has to be 'implanted' in the 'fruitful field'. Only then can a 'baby' develop, possibly during the 'barred months', to be delivered by the 'bat' in Zotz:

The vertical 'toothache' band (of the 'sun', the ruler) alludes, I think, to the 'Tree', but also to the 'banded headdress'. In the following season, the band is no longer vertical and another band is 'crossed' with it, viz. the band of the moon - cfr Pop, Uo, and Zip. The vertical band, in stylized form, is a necessary sign in what Gates pointed at as a possible glyph for haab:

"It is at present a bare suggestion; but we have not yet verified a glyph that must surely exist in what texts we have, namely for the haab, or solar year. The peculiar position and repetition of this 331.2.1 on the first side of the Paris codex, in Madrid tz. 125, and in the Dresden, have suggested this as a candidate for that meaning. It occurs besides on the New Year pages, both Madrid and Dresden, where such a glyph should by all means be expected." (Gates) Reading Kelley I have, furthermore, stumbled on a possible connection between Seven Macaw and the moko glyph type. I cannot get it out of my head, so I have to document it:

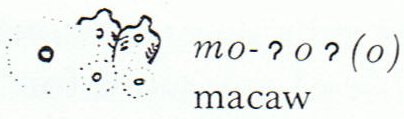

As one of Kelley's examples of how to phonetically read the Maya glyphs he has chosen 'macaw':

The glottal stop is close to the sound of k. Instead of the vowel a (in macaw) the Mayans used o. As to the last o within parenthesis: "... I strongly suspect that when the script was developed, some or all of the Mayan languages still preserved a final vowel on words which now end with a consonant ..." (Kelley) The resemblance between the Mayan and Polynesian dialects thereby increases. Also, on Easter Island mago alternatively could be pronounced mogo:

I suggest the shark (mago) is conceptually related to the lizard (moko). We know that Imix was a kind of 'sea dragon'. When Hawaiian Ulu (presumably alluding to 'head') understood he had to die in order for his son to live, he went to the nobel Mo'o: ... When the man, Ulu, returned to his wife from his visit to the temple at Puueo, he said, 'I have heard the voice of the noble Mo'o, and he has told me that tonight, as soon as darkness draws over the sea and the fires of the volcano goddess, Pele, light the clouds over the crater of Mount Kilauea, the black cloth will cover my head. And when the breath has gone from my body and my spirit has departed to the realms of the dead, you are to bury my head carefully near our spring of running water. Plant my heart and entrails near the door of the house. My feet, legs, and arms, hide in the same manner. Then lie down upon the couch where the two of us have reposed so often, listen carefully throughout the night, and do not go forth before the sun has reddened the morning sky. If, in the silence of the night, you should hear noises as of falling leaves and flowers, and afterward as of heavy fruit dropping to the ground, you will know that my prayer has been granted: the life of our little boy will be saved.' And having said that, Ulu fell on his face and died ... Thus the moko concept is connected with the end, the head, and with fire. Seven Macaw is neither a lizard nor a shark. But his colours betray him: ... Men and birds joined forces to destroy the huge watersnake, which dragged all living creatures down to his lair. But the attackers took fright and cried off, one after the other, offering as their excuse that they could only fight on dry land. Finally, the duckler ... was brave enough to dive into the water; he inflicted a fatal wound on the monster which was at the bottom, coiled round the roots of an enormous tree. Uttering terrible cries, the men succeeded in bringing the snake out of the water, where they killed it and removed its skin. The duckler claimed the skin as the price of its victory. The Indian chiefs said ironically, 'By all means! Just take it away!' 'With pleasure', replied the duckler as it signalled to the other birds. Together they swooped down and, each one taking a piece of the skin in its beak, flew off with it. The Indians were annoyed and angry and, from then on, became the enemies of birds. The birds retired to a quiet spot in order to share the skin. They agreed that each one should keep the part that was in its own beak. The skin was made up of marvelous colors - red, yellow, green, black, and white - and had markings such as no one had ever seen before. As soon as each bird was provided with the part to which it was entitled, the miracle happened: until that time all birds had had dingy plumage, but now suddenly they became white, yellow, and blue ... The parrots were covered in green and red, and the macaws with red, purple, and gilded feathers, such as had never before been seen. The duckler, to which all the credit was due, was left with the head, which was black. But it said it was good enough for an old bird ... The huge watersnake of course must be Imix and a species of moko / mago. Seven Macaw therefore is connected with the moko. The word mo'o'o for macaw is close to Hawaiian mo'o. In Easter Island mythology the moko is related to the concept of being 'down in the earth': ... When Tuu Ko Ihu came out and sat on the stone underneath which he had buried the skull, Ure Honu shot into the house like a lizard. He lifted up the one side of the house. Then Ure Honu let it fall down again; he had found nothing. Ure Honu called, 'Dig up the ground and continue to search!' ....Jaussen (according to Barthel): ... A une certaine saison, on amassait des vivres, on faisait fête On emmaillotait un corail, pierre de défunt lezard, on l'enterrait, tanu. Cette cérémonie était un point de départ pour beacoup d'affaires, notamment de vacances pour le chant des tablettes ou de la priére, tanu i te tau moko o tana pure, enterrer la pierre sépulcrale de lézard de sa prière ... ... We have seen how for example the Aztecs ordered the lizard close to the snake and death in their 20-day week:

Beyond Cuetzpallin, the lizard, follows the serpent and then death. Then a reception by the 'deer', because the Manik sign means not only 'to grasp' but also 'deer':

The name 'coco-nut palm' (niu) implies coco (as in mo'o'o), nut (as in the head of Ulu) and palm as inside the grasping Manik. ... When viewed on end, the endocarp and germination pores give the fruit the appearance of a coco (also Côca), a Portuguese word for a scary witch from Portuguese folklore, that used to be represented as a carved vegetable lantern, hence the name of the fruit. The specific name nucifera is Latin for nut-bearing ...

|