In

ancient Egypt they thought Sirius was behind the yearly rise of the Nile.

... the

seasonal cycle, throughout the ancient world, was the

foremost sign of rebirth following death, and in Egypt

the chronometer of this cycle was the annual flooding of

the Nile. Numerous festival edifices were constructed,

incensed, and consecrated; a throne hall wherein the

king should sit while approached in obeisance by the

gods and their priesthoods (who in a crueler time would

have been the registrars of his death); a large court

for the presentation of mimes, processions, and other

such visual events; and finally a palace-chapel into

which the god-king would retire for his changes of

costume ...

... Pliny

wants to assure us that 'the whole sea is conscious of

the rise of that star, as is most clearly seen in the

Dardanelles, for sea-weed and fishes float on the

surface, and everything is turned up from the bottom'.

He also remarks that at the rising of the Dog-Star the

wine in the cellars begins to stir up and that the still

waters move

...

... the

modern Homo occidentalis is bound to shrink back

from the mere idea that the Nile represented a circle,

where 'source' and 'mouth' meet, so that there is

nothing preposterous in the notion that a Canopic mouth

can be found in the geographical North

...

In Polynesia the myths

told about how new Land was

fished up by Maui (or some other hero) and this idea

resembles how sea-weed and fishes were drawn up by Sirius (making the still waters come alive).

Hatiga te Kohe (Broken Staff) came before Roto Iri

Are (Sea Weed) in the sequence of dream soul stations,

and then she reached Tama (the Child):

... The dream

soul went on. She was careless (?) and broke the kohe

plant with her feet. She named the place 'Hatinga Te

Koe A Hau Maka O Hiva'.

The

dream soul went on and came to Roto Ire Are. She

gave the name 'Roto Ire Are A Hau Maka O Hiva'.

The dream soul went on and came to Tama. She

named the place 'Tama', an evil fish (he ika

kino) with a very long nose (he ihu roroa)

...

| Hati

Hati 1. To break (v.t.,

v.i.); figuratively: he hati te pou oka, to

die, of a hopu manu in the exercise of his

office (en route from Motu Nui to Orongo).

2. Closing word of certain songs. Vanaga.

Hahati. 1. To break (see

hati). 2. Roughly treated, broken (from physical

exertion: ku hahati ß te hakari) 3. To take

to the sea: he hahati te

vaka. Vanaga.

Ha(ha)ti. To strike, to

break, to peel off bark; slip, cutting, breaking,

flow, wave (aati, ati, hahati);

tai hati, breakers, surf; tumu hatihati,

weak in the legs; hakahati, to persuade;

hatipu, slate. P Pau.: fati, to break.

Mgv.: ati, hati, to break, to smash.

Mq.: fati, hati, id. Ta.: fati,

to rupture, to break, to conquer. Churchill.

|

| HAKI, v.

Haw., also ha'i and ha'e, primary

meaning to break open, separate, as the lips about

to speak, to break, as a bone or other brittle

thing, to break off, to stop, tear, rend, to speak,

tell, bark as a dog; hahai, to break away,

follow, pursue, chase; hai, a broken place, a

joint; hakina, a portion, part; ha'ina,

saying; hae, something torn, as a piece of

kapa or cloth, a flog, ensign. Sam., fati,

to break, break off; fa'i, to break off,

pluck off, as a leaf, wrench off; fai, to

say, speak, abuse, deride; sae, to tear off,

rend; ma-sae, torn. Tah., fati, to

break, break up, broken; fai, confess,

reveal, deceive; faifai, to gather or pick

fruit; haea, torn, rent; s. deceit,

duplicity; hae-hae, tear anything, break an

agreement; hahae, id. Tong., fati,

break, rend. Marqu., fati, fe-fati, to

break, tear, rend; fai, to tell, confess;

fefai, to dispute. The same double meaning of

'to break' and 'to say' is found in the New Zealand

and other Polynesian dialects. Malg., hai,

ha´k, voice, address, call.

Lat., seco, cut off, cleave,

divide; securis, hatchet; segmentum,

cutting, division, fragment; seculum (sc.

temporis), sector, follow eagerly, chase,

pursue; sequor, follow; sica, a

dagger; sicilis, id., a knife; saga,

sagus, a fortune-teller. Greek, άγνυμι,

break, snap, shiver, from Ѓαγ

(Liddell and Scott); άγν, breakage,

fragment; έκας,

adv, far off, far away.

Liddell and

Scott consider έκας akin to

έκαςτος,

each, every, 'in the sense of apart, by itself', and

they refer to the analysis of Curtius ... comparing

Sanskrit kas,

kÔ,

kat (quis,

qua,

quid),

who of two, of many, &c. Doubtless

έκας

and

έκαςτος are akin 'in the

sense of apart, by itself', but that sense arises

from the previous sense of separating, cutting off,

breaking off, and thus more naturally connects

itself with the Latin

sec-o,

sac-er,

and that family of words and ideas, than with such a

forced compound as

είς and κας.

Sanskr.,

sach, to follow. Zend, hach, id. (Vid.

Haug, 'Essay on Parsis'.) I am

well aware that most, perhaps all, prominent

philologists of the present time - 'whose

shoe-strings I am not worthy to unlace' - refer the

Latin sequor,

secus,

even sacer,

and the Greek έπω,

έπομαι, to this Sanskrit sach. Benfey

even refers the Greek έκας to this sach,

as explanatory of its origin and meaning.

But, under correction, and even without the

Polynesian congeners, I should hold that sach,

'to follow', in order to be a relative to sacer,

doubtless originally meaning 'set apart', then

'devoted, holy', and of έκας, 'far off',

doubtless originally meaning something 'separated',

'cut off from, apart from', must also originally

have had a meaning of 'to be separated from, apart

from', and then derivatively 'to come after, to

follow'. The sense of 'to follow' implies the sense

of 'to be apart from, to come after', something

preceding. The links of this connection in sense are

lost in Sanskrit, but still survive in the

Polynesian haki, fati, and its

contracted form hai, fai, hahai,

as shown above. I am therefore inclined to rank the

Latin sequor as a derivative of seco, 'to cut

off, take off'.

Welsh,

haciaw, to hack; hag, a gash, cut;

segur, apart, separate; segru, to put

apart; hoc, a bill-hook; hicel, id.

A.-Sax., saga, a saw; seax, knife;

haccan, to cut, hack; sŠgan, to saw;

saga, speech, story; secan, to seek. Anc.

Germ., seh, sech, a ploughshare.

Perhaps the Goth. hakul, A.-Sax. hacele,

a cloak, ultimately refer themselves to the Polynes.

hae, a piece of cloth, a flag.

Anc. Slav.,

sieshti (siekā), to cut; siekyra,

hatchet. Judge Andrews in his Hawaiian-English

Dictionary observes the connection in Hawaiian ideas

between 'speaking, declaring', and 'breaking'. The

primary idea, which probably underlies both, is

found in the Hawaiian 'to open, to separate, as the

lips in speaking or about to speak'; and it will be

observed that the same development in two directions

shows itself in all the Polynesian diaclects, as

well as in several of the West Aryan dialects also.

(Fornander) |

| Kohe

A plant (genus Filicinea) that

grows on the coast. Vanaga.

Vave kai kohe,

inaccessible. Churchill.

*Kofe is the name for

bamboo on most Polynesian islands, but today on

Easter Island kohe is the name of a fern that

grows near the beach. Barthel 2. |

|

Roto

1. Inside. 2. Lagoon (off the coast,

in the sea). 3. To press the juice out of a plant;

taheta roto pua, stone vessel used for

pressing the juice out of the pua plant, this

vessel is also just called roto. Roto o

niu, east wind. Vanaga.

1. Marsh, swamp, bog; roto nui,

pond; roto iti, pool. 2. Inside, lining; o

roto, interior, issue; ki roto, within,

into, inside, among; mei roto o mea, issue;

no roto mai o mea, maternal; vae no roto,

drawers. Churchill. |

| Iri

1. To go up; to go in a boat on the

sea (the surface of which gives the impression of

going up from the coast): he-eke te tagata ki

ruga ki te vaka, he-iri ki te Hakakaiga, the men

boarded the boat and went up to Hakakainga.

2. Ka-iri ki puku toiri ka toiri. Obscure

expression of an ancient curse. Vanaga.

Iri-are, a seaweed. Vanaga. |

| Are

To dig out (e.g. sweet potatoes).

Formerly this term only applied to women, speaking

of men one said keri, which term is used

nowadays for both sexes, e.g. he-keri i te

kumara, he digs out sweet potatoes. Vanaga.

To dig, to excavate. Churchill. |

|

Tama

1. Shoot (of plant), tama miro,

tree shoot; tama t˘a, shoot of sugarcane.

2. Poles, sticks, rods of a frame. 3. Sun rays. 4.

Group of people travelling in formation. 5. To

listen attentively (with ear, tariga, as

subject, e.g. he tama te tariga); e-tama

rivariva tokorua tariga ki taaku kţ, listen

carefully to my words. Tamahahine, female.

Tamahine (= tamahahine), female, when

speaking of chickens: moa tamahine, hen.

TamÔroa, male. Vanaga.

1. Child. P Pau.: tama riki,

child. Mgv.: tama, son, daughter, applied at

any age. Mq.: tama, son, child, young of

animals. Ta.: tama, child. Tamaahine (tama

1 - ahine), daughter, female. Tamaiti,

child P Mq.: temeiti, temeii, young

person. Ta.: tamaiti, child. Tamaroa,

boy, male. P Mgv.: tamaroa, boy, man, male.

Mq.: tamaˇa, boy. Ta.: tamaroa, id. 2.

To align. Churchill.

In the Polynesian this [tama na,

father in the EfatÚ language] is distinguished from

tßma child by the accent tamā

or by the addition of a final syllable which

automatically secures the same incidence of the

accent, tamßi,

tamana

... Churchill 2 |

... The brothers

had no idea what Maui was up to now, as he paid out his

line. Down, down it sank, and when it was at the bottom Maui

lifted it slightly, and it caught on something which at once

pulled very hard.

Maui

pulled also, and hauled in a little of his line. The canoe

heeled over, and was shipping water fast. 'Let it go!' cried

the frightened brothers, but Maui answered with the words

that are now a proverb: 'What Maui has got in his hand he

cannot throw away.'

'Let go?'

he cried. 'What did I come for but to catch fish?' And he

went on hauling in his line, the canoe kept taking water,

and his brothers kept bailing frantically, but Maui would

not let go.

Now Maui's hook

had caught in the barge-boards of the house of Tonganui, who

lived at the bottom of that part of the sea and whose name

means Great South; for it was as far to the south that the

brothers had paddled from their home. And Maui knew what it

was that he had caught, and while he hauled at his line he

was chanting the spell that goes:

O Tonganui / why

do you hold so stubbornly there below?

The power of

Muri's jawbone is at work on you, / you are coming, / you

are caught now, / you are coming up, / appear, appear.

Shake yourself, /

grandson of Tangaroa the little.

The fish came

near the surface then, so that Maui's line was slack for a

moment, and he shouted to it not to get tangled.

But then

the fish plunged down again, all the way to the bottom. And

Maui had to strain, and haul away again. And at the height

of all this excitement his belt worked loose, and his

maro fell off and he had to kick it from his feet.

He had to do the rest

with nothing on.

The

brothers of Maui sat trembling in the middle of the canoe,

fearing for their lives. For now the water was frothing and

heaving, and great hot bubbles were coming up, and steam,

and Maui was chanting the incantation called Hiki,

which makes heavy weights light.

At length

there appeared beside them the gable and thatched roof of

the house of Tonganui, and not only the house, but a huge

piece of the land attached to it. The brothers wailed, and

beat their heads, as they saw that Maui had fished up land,

Te Ika a Maui, the fish of Maui. And there were

houses on it, and fires burning, and people going about

their daily tasks. Then Maui hitched his line round one of

the paddles laid under a pair of thwarts, and picked up his

maro, and put it on again

...

(Antony

Alpers, Maori Myths & Tribal Legends.)

| Maro

Maro: A sort of small banner

or pennant of bird feathers tied to a stick.

Maroa: 1. To stand up, to stand. 2. Fathom

(measure). See kumi. Vanaga.

Maro: 1. June. 2.

Dish-cloth T P Mgv.: maro, a small girdle or

breech clout. Ta.: maro, girdle. Maroa:

1. A fathom; maroa hahaga, to measure. Mq.:

maˇ, a fathom. 2. Upright, stand up, get up,

stop, halt. Mq.: maˇ, to get up, to stand up.

Churchill.

Pau.: Maro, hard, rough,

stubborn. Mgv.: maro, hard, obdurate, tough.

Ta.: mÔr˘, obstinate, headstrong. Sa.:

mālō, strong. Ma.:

maro,

hard, stubborn. Churchill.

Ta.:

Maro,

dry, desiccated. Mq.: mao,

thirst, desiccated. Fu.:

malo,

dry. Ha.: malo,

maloo,

id. Churchill.

Mgv.:

Maroro,

the flying fish. (Ta.:

marara,

id.) Mq.: maoo,

id. Sa.: malolo,

id. Ma.: maroro,

id. Churchill. |

MALO ╣,

s. Haw., a strip of kapa or cloth tied

around the loins of men to hide the sexual

organs. Polynesian, ubique, malo, maro,

id., ceinture, girdle-cloth, breech-cloth.

Sanskr., mal,

mall, to hold; malla, a cup;

maltaka, a leaf to wrap up something, a cup;

malÔ-mallaka, a piece of cloth worn over

the privities..

Greek,

μηρνομαι; Dor., μαρνομαι, to draw up,

furl, wind round. No etymon in Liddell and

Scott.

MALO ▓,

v. Haw., to dry up, as water in pools or

rivers, be dry, as land, in opposition to water,

to wither, as vegetables drying up; maloo,

id., dry barren.

Ta., maro,

dry, not wet; marohi, dry, withered. A

later application of this word in a derivative

sense is probably the Sam. malo, to be

hard, be strong; malosi, strong; the

Marqu. mao, firm, solid; N. Zeal.,

maroke, dry; Rarot., Mang., maro, dry

and hard, as land.

Sanskr., mŗi,

to die; maru,

a desert, a mountain; marut,

the deities of wind; marka,

a body; markara,

a barren woman; mart-ya,

a mortar, the earth; mţra,

ocean.

For the

argument by which A. Pictet connects

maru

and mira

with mŗi,

see 'Orig. Ind.Eur', i. 110-111. It is doubtless

correct. But in that case 'to die' could hardly

have been the primary sense or conception of

mŗi.

To the early Aryans the desert, the

maru,

which approached their abodes on the west, must

have presented itself primarily under the aspect

of 'dry, arid, sterile, barren', a sense still

retained in the Polynesian

maro.

Hence the sense of 'to wither, to die', is a

secondary one. Again, those ancient Aryans

called the deity of the wind the

Marut;

and if that word, as it probably does, refers

itself to the root or stem

mŗi,

the primary sense of that word was certainly not

'to die', for the winds are not necessarily

'killing', but they are 'drying', and that is

probably the original sense of their name.

Lat.,

morior,

mors,

&c. Sax., mor,

Eng., moor,

equivalent to the Sanskr.

maru.

(Fornander)

|

We can compare

the fish-hook of Maui with that in Ga2-11, in ░June 30,

in day 100 + 1 counted

from ░March 21 and day 60 counted

from ░May 1:

|

APRIL 29 |

30 (*40) |

MAY 1 (11 * 11) |

2 (122) |

|

|

|

|

|

Ga2-9 |

Ga2-10 |

Ga2-11 |

Ga2-12 (42) |

|

Mash-mashu-sha-Risū-9 (Twins of the

Shepherd ?) |

ADARA = ε Canis Majoris

(104.8) |

ω Gemini

(105.4),

ALZIRR = ξ Gemini

(105.7),

MULIPHEIN = γ Canis Majoris

(105.8),

MEKBUDA = ζ Gemini

(105.9) |

7h (106.5) |

|

θ Gemini (103.0), ψ8 Aurigae (103.2),

ALHENA = γ Gemini

(103.8), ψ9 Aurigae (103.9) |

no star listed (106) |

|

July 2 |

(*104 = 8 * 13) |

4 (185) |

5 |

|

║June 28 |

29 (*100) |

SIRIUS |

║July 1 (182) |

|

'June 5 |

6 (157) |

7 (*78) |

8 |

|

NAKSHATRA DATES: |

|

OCTOBER 29 |

30 (303) |

31 (*224) |

NOVEMBER 1 |

|

χ Oct.

(286.0),

AIN AL RAMI = ν Sagittarii

(286.2), υ

Draconis (286.4), δ Lyrae (286.3),

κ Pavonis

(286.5),

ALYA = θ Serpentis

(286.6) |

ξ Sagittarii

(287.1),

ω Pavonis

(287.3), ε

Aquilae, ε Cor. Austr.,

SULAPHAT = γ Lyrae

(287.4), λ Lyrae (287.7),

ASCELLA

= ζ Sagittarii, BERED = i Aquilae

(Ant.)

(287.9) |

Al Na'ām-18 /

Uttara Ashadha-21 |

19h (289.2) |

|

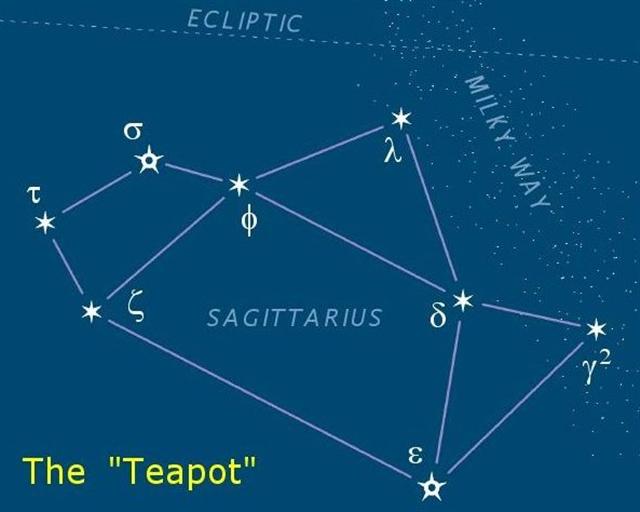

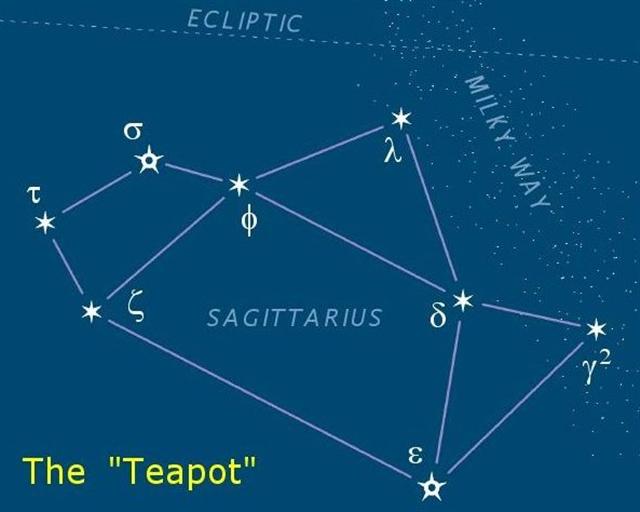

NUNKI

= σ Sagittarii

(288.4), ζ Cor. Austr. (288.5),

MANUBRIUM = ο Sagittarii

(288.8),

ζ Aquilae (288.9) |

λ Aquilae (Ant.)

(289.1), γ Cor. Austr (289.3),

τ Sagittarii

(289.4), ι Lyrae (289.5), δ Cor. Austr.

(289.8) |

|

January 1 |

2 |

3 (368) |

4 |

|

░December 28 |

29 |

30 (364) |

31 |

|

'December 5 |

6 (340) |

7 (*261) |

8 |

Close

to the Full Moon were Ascella and Nunki in

Sagittarius, which meant that when Sirius

was at the Sun then the Full Moon would had been

where the Sea was said to begin. At the time of

Gregory XIII this was in day 364 counted from

░January 1. Land was beginning

in ░June 30 and its opposite, Sea, was

originating

in ░December 31. 'Land' ('summer') began at

the opposite side of the sky compared to the

beginning of the 'Sea' ('winter').

...

This [σ]

has been identified with Nunki of the

Euphratean Tablet of the Thirty Stars,

the Star of the Proclamation of the Sea,

this Sea being the quarter occupied

by Aquarius, Capricornus, Delphinus, Pisces,

and Pisces Australis. It is the same space

in the sky that Aratos designated as

Water ... (Allen)

... 'Tell us a

story!' said the March Hare. 'Yes, please do!' pleaded Alice.

'And be quick about it', added the Hatter, 'or you'll be asleep

again before it's done.' 'Once upon a time

there were three little sisters', the Dormouse began in a great

hurry: 'and their names were Elsie, Lacie, and Tillie; and they

lived at the bottom of a well Ś

'

'What did they live

on?' said Alice, who always took a great interest in questions

of eating and drinking. 'They lived on treacle,' said the

Dormouse, after thinking a minute or two. 'They couldn't have

done that, you know', Alice gently remarked. 'They'd have been

ill.' 'So they were', said the Dormouse; 'very ill'.

Alice tried a little to fancy herself what such an extraordinary

way of living would be like, but it puzzled her too much: so she

went on : 'But why did they live at the bottom of a well?'

'Take some more tea

[= t as in duration of time]', the March Hare said to Alice,

very earnestly. 'I've had nothing yet', Alice replied in an

offended tone: 'so I can't take more [<]'.

'You mean

you can't take less

[>]',

said the Hatter:

'it's very easy to take more than nothing'. 'Nobody asked

your opinion', said

Alice. 'Who's making personal remarks now?' the Hatter remarked

triumphantly.

Alice did not quite

know what to say to this: so she helped herself to some tea and

bread-and-butter, and then turned to the Dormouse, and repeated

her question. 'Why did they live at the bottom of a well?' The

Dormouse again took a minute or two to think about it, and then

said 'It was a treacle-well.' 'There's no such thing!' Alice was

beginning very angrily, but the Hatter and the March Hare went

'Sh! Sh!' and the Dormouse sulkily remarked 'If you ca'n't be

civil, you'd better finish the story for yourself.' 'No, please

go on!' Alice said very humbly. 'I wo'n't interrupt you again. I

dare say there may be one.'

'One,

indeed!' said the Dormouse indignantly. However, he consented to

go on. 'And so these three little sisters - they were learning

to draw, you know Ś' 'What did they draw?' said Alice, quite

forgetting her promise. 'Treacle', said the Dormouse, without

considering at all, this time.

'I wan't a clean

cup', interrupted the Hatter: 'let's all move one place on.' He

moved as he spoke, and the Dormouse followed him: the March Hare

moved into the Dormouse's place, and Alice rather unwillingly

took the place of the March Hare. The Hatter was the only one

who got any advantage from the change; and Alice was a good deal

worse off than before, as the March Hare had just upsed the

milk-jug into his plate ...

|