From the time of the introduction of the Gregorian calendar (in 1582 A.D.) to the time I have chosen to use as a year of reference for the rongorongo writers (1842 A.D.) the precession would have moved the stars ahead with about (1842 - 1582) / 71 = ca 4 days (glyphs). We can therefore add this piece of information in form of yet another set of dates, corresponding to the positions of the stars at the time of Gregory XIII:

The Gregorian calendar was constructed with Sirius as its 'leading star', rising at the end of the first half of the year (and 60 days later than May 1):

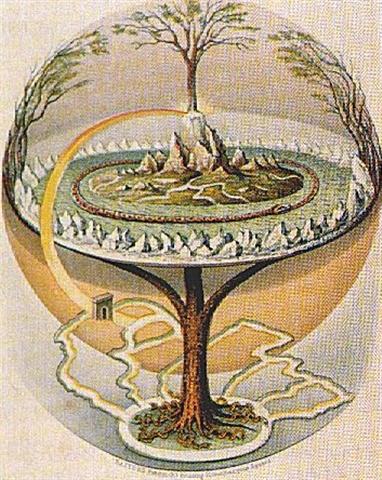

This could explain why the Egyptians had a cow instead of the bull, why Hathor was the heart of all the circuits. It was because the Bull was remembered to be the place where once upon a time the northern spring equinox had been and beyond the death of Father Light (Jupiter) in high summer there had to be a kind of interregnum before a new king could be installed. Although the creator of the G text could have ignored the proper motions of the stars he certainly would have known Sirius was a special case: ... The Sothic cycle was based on what is referred to in technical jargon as 'the periodic return of the heliacal rising of Sirius', which is the first appearance of this star after a seasonal absence, rising at dawn just ahead of the sun in the eastern portion of the sky. In the case of Sirius the interval between one such rising and the next amounts to exactly 365.25 days - a mathematically harmonious figure, uncomplicated by further decimal points, which is just twelve minutes longer than the duration of the solar year ... (Graham Hancock, Fingerprints of the Gods.) On Easter Island one of the names for Sirius was Te Pou (pillar, pole, etc), perhaps because it was not affected by the precession - this star pillar stood unmoved in the flow of time. ... pou meaning column, pillar or post of either stone or wood. Sometimes the word is applied to a natural rock formation with postlike qualities which serves as an orientation point. The star Sirius is called Te Pou in Rapanui and functions in the same way. (Jo Anne Van Tilburg, Easter Island. Archeology, Ecology and Culture. )

It always was in June 30. When 6 (as in June, the 6th month) of his 12 men had been eaten, Odysseus stopped the 1-eyed Polyphemus by using a fiery wooden pole: ... Odysseus and his fleet were now in a mythic realm of difficult trials and passages, of which the first was to be the Land of the Cyclopes, 'neither nigh at hand, nor yet afar off', where the one-eyed giant Polyphemus, son of the god Poseidon (who, as we know, was the lord of tides and of the Two Queens, and the lord, furthermore, of Medusa), dwelt with his flocks in a cave. 'Yes, for he was a monstrous thing and fashioned marvelously, nor was he like to any man that lives by bread, but like a wooded peak of the towering hills, which stands out apart and alone from others.' Odysseus, choosing twelve men, the best of the company, left his ships at shore and sallied to the vast cave. It was found stocked abundantly with cheeses, flocks of lambs and kids penned apart, milk pails, bowls of whey; and when the company had entered and was sitting to wait, expecting hospitality, the owner came in, shepherding his flocks. He bore a grievous weight of dry wood, which he cast down with a din inside the cave, so that in fear all fled to hide. Lifting a huge doorstone, such as two and twenty good four-wheeled wains could not have raised from the ground, he set this against the mouth of the cave, sat down, milked his ewes and goats, and beneath each placed her young, after which he kindled a fire and spied his guests. Two were eaten that night for dinner, two the next morning for breakfast, and two the following night. (Six gone.) But the companions meanwhile had prepared a prodigous stake with which to bore out the Cyclops' single eye; and when clever Odysseus, declaring his own name to be Noman, approached and offered the giant a skin of wine, Polyphemus, having drunk his fill, 'lay back', as we read, 'with his great neck bent round, and sleep that conquers all men overcame him.' Wine and fragments of the men's flesh he had just eaten issued forth from his mouth, and he vomited heavy with drink. 'Then', declared Odysseus, I thrust in that stake under the deep ashes, until it should grow hot, and I spake to my companions comfortable words, lest any should hang back from me in fear. But when that bar of olive wood was just about to catch fire in the flame, green though it was, and began to glow terribly, even then I came nigh, and drew it from the coals, and my fellows gathered about me, and some god breathed great courage into us. For their part they seized the bar of olive wood, that was sharpened at the point, and thrust it into his eye, while I from my place aloft turned it about, as when a man bores a ship's beam with a drill while his fellows below spin it with a strap, which they hold at either end, and the auger runs round continually. Even so did we seize the fiery-pointed brand and whirled it round in his eye, and the blood flowed about the heated bar. And the breath of the flame singed his eyelids and brows all about, as the ball of the eye burnt away, and the roots thereof crackled in the flame. And as when a smith dips an ax or adze in chill water with a great hissing, when he would temper it - for hereby anon comes the strength of iron - even so did his eye hiss round the stake of olive. And he raised a great and terrible cry, that the rock rang around, and we fled away in fear, while he plucked forth from his eye the brand bedabbled in much blood. Then maddened with pain he cast it from him with his hands, and called with a loud voice on the Cyclopes, who dwelt about him in the caves along the windy heights. And they heard the cry and flocked together from every side, and gathering round the cave, called in to ask what ailed him. 'What hath so distressed thee, Polyphemus, that thou criest thus aloud through the immortal night, and makest us sleepless? Surely no mortal driveth off thy flocks against thy will: surely none slayeth thyself by force or craft?' And the strong Polyphemus spake to them again from out of the cave: 'My friends, Noman is slaying me by guile, nor at all by force.' And they answered and spake winged words: 'If then no man is violently handling thee in thy solitude, it can in no wise be that thou shouldst escape the sickness sent by mighty Zeus. Nay, pray thou to thy father, the lord Poseidon.' On this wise they spake and departed; and my heart within me laughed to see how my name and cunning counsel had beguiled him ... (Joseph Campbell, The Masks of God: Occidental Mythology.)

... A man had a daughter who possessed a wonderful bow and arrow, with which she was able to bring down everything she wanted. But she was lazy and was constantly sleeping. At this her father was angry and said: 'Do not be always sleeping, but take thy bow and shoot at the navel of the ocean, so that we may get fire.' The navel of the ocean was a vast whirlpool in which sticks for making fire by friction were drifting about. At that time men were still without fire. Now the maiden seized her bow, shot into the navel of the ocean, and the material for fire-rubbing sprang ashore. Then the old man was glad. He kindled a large fire, and as he wanted to keep it to himself, he built a house with a door which snapped up and down like jaws and killed everybody that wanted to get in. But the people knew that he was in possession of fire, and the stag determined to steal it for them. He took resinous wood, split it and stuck the splinters in his hair. Then he lashed two boats together, covered them with planks, danced and sang on them, and so he came to the old man's house. He sang: 'O, I go and will fetch the fire.' The old man's daughter heard him singing, and said to her father: 'O, let the stranger come into the house; he sings and dances so beautifully.' The stag landed and drew near the door, singing and dancing, and at the same time sprang to the door and made as if he wanted to enter the house. Then the door snapped to, without however touching him. But while it was again opening, he sprang quickly into the house. Here he seated himself at the fire, as if he wanted to dry himself, and continued singing. At the same time he let his head bend forward over the fire, so that he became quite sooty, and at last the splinters in his hair took fire. Then he sprang out, ran off and brought the fire to the people ... (From the Catlo'Itq in British Columbia according to Hamlet's Mill.) But at the time of the First Point of Aries the pole star in the north (Polaris) would have been in the day before the northern spring equinox and the 'pole star' in the south (Te Pou, Sirius) at the door to a new 'year': ... The seventh tree is the oak, the tree of Zeus, Juppiter, Hercules, The Dagda (the chief of the elder Irish gods), Thor, and all the other Thundergods, Jehovah in so far as he was 'El', and Allah. The royalty of the oak-tree needs no enlarging upon: most people are familiar with the argument of Sir James Frazer's Golden Bough, which concerns the human sacrifice of the oak-king of Nemi on Midsummer Day. The fuel of the midsummer fires is always oak, the fire of Vesta at Rome was fed with oak, and the need-fire is always kindled in an oak-log. When Gwion writes in the Câd Goddeu, 'Stout Guardian of the door, His name in every tongue', he is saying that doors are customarily made of oak as the strongest and toughest wood and that 'Duir', the Beth-Luis-Nion name for 'Oak', means 'door' in many European languages including Old Goidelic dorus, Latin foris, Greek thura, and German tür, all derived from the Sanskrit Dwr, and that Daleth, the Hebrew letter D, means 'Door' - the 'l' being originally an 'r'. Midsummer is the flowering season of the oak, which is the tree of endurance and triumph, and like the ash is said to 'court the lightning flash'. Its roots are believed to extend as deep underground as its branches rise in the air - Virgil mentions this - which makes it emblematic of a god whose law runs both in Heaven and in the Underworld ... The month, which takes its name from Juppiter the oak-god, begins on June 10th and ends of July 7th. Midway comes St. John's Day, June 24th, the day on which the oak-king was sacrificially burned alive. The Celtic year was divided into two halves with the second half beginning in July, apparently after a seven-day wake, or funeral feast, in the oak-king's honour ... (Robert Graves, The White Goddess).

... In north Asia the common mode of reckoning is in half-year, which are not to be regarded as such but form each one separately the highest unit of time: our informants term them 'winter year' and 'summer year'. Among the Tunguses the former comprises 6½ months, the latter 5, but the year is said to have 13 months; in Kamchatka each contains six months, the winter year beginning in November, the summer year in May; the Gilyaks on the other hand give five months to summer and seven to winter. The Yeneseisk Ostiaks reckon and name only the seven winter months, and not the summer months. This mode of reckoning seems to be a peculiarity of the far north: the Icelanders reckoned in misseri, half-years, not in whole years, and the rune-staves divide the year into a summer and a winter half, beginning on April 14 and October 14 respectively. But in Germany too, when it was desired to denote the whole year, the combined phrase 'winter and summer' was employed, or else equivalent concrete expressions such as 'in bareness and in leaf', 'in straw and in grass' ... (Martin P. Nilsson, Primitive Time-Reckoning.) The pole in a gnomon had to be straight and the bent curves in Gb7-24 and Ga1-3 must have illustrated something else. Perhaps the bent curve illustrated old age, the last stage in an old circuit, and the newborn cycle should then stand straight:

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||