30. The Mad Hatter had a Sign in his oversized hat, a price label which alluded to the month of Jupiter (In this Style 10 / 6). ... The month, which takes its name from Juppiter the oak-god, begins on June 10th and ends of July 7th. Midway comes St. John's Day, June 24th, the day on which the oak-king was sacrificially burned alive. The Celtic year was divided into two halves with the second half beginning in July, apparently after a seven-day wake, or funeral feast, in the oak-king's honour ...

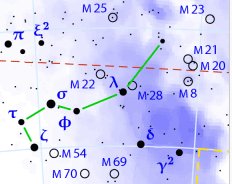

'Twinkle, twinkle, little bat!' // How I wonder what you're at!' And the Chinese list had the South Dipper (Tea Pot with Φ Sagittarii) as their 8th station:

... The medieval Dutch poem of Brandaen ... contains a very remarkable feature: Brandaen met on the sea a man of thumb size, floating upon a leaf, holding in his right hand a small bowl, in the left hand a stylus; the stylus he kept dipping into the sea and letting water drip from it into the bowl; when the bowl was full, he emptied it out, and began filling it again. It was imposed on him, he said, to measure the sea until Judgment-day. The particular kind of 'instrument' seems to reveal the surveyor in charge in this special case. Mercury was the celestial scribe and guardian of the files and records, 'and he was the inventor of many arts, such as arithmetic and calculation and geometry and astronomy and draughts and dice, but his great discovery was the use of letters', as Plato has it (Phaedrus 274). It remains to be seen whether or not all the measuring planets can be recognized by their particular methods of doing the measuring. It is known how Saturn does it, and Jupiter. Jupiter 'throws', and Saturn 'falls' ... The pointed stylus of Mercury may have contributed to the word 'Style' in the Mad Hatter's Hat. However, the stylus was also alluding to the gnomon pointer.

The star at the navel (middle) of Pollux was named Wasat (Middle) by the Arabs. At the time of rongorongo, when precession had restored the positions of the stars to their proper places in the Gregorian calendar, Wasat (δ Gemini) rose with the Sun in July 8:

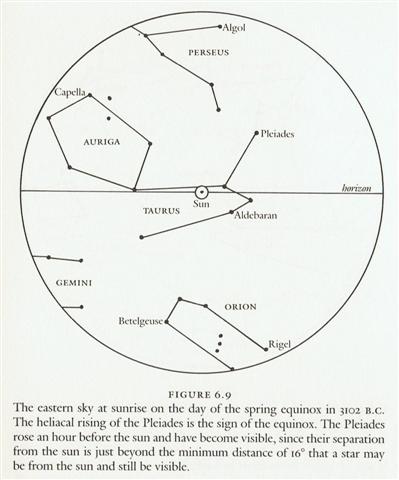

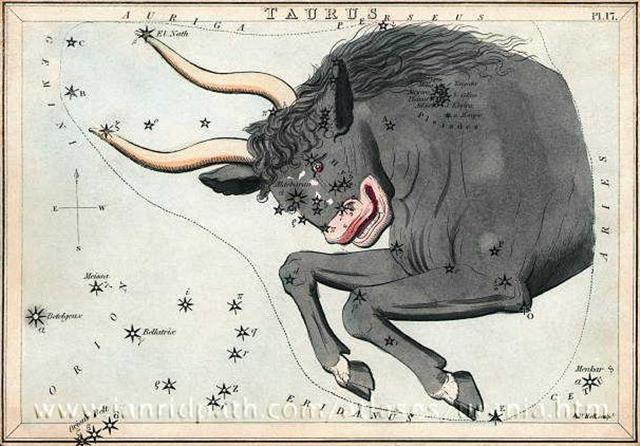

The midpoint of the month of Jupiter came at Canopus and its beginning was in June 10 at heliacal Nihal (β Leporis) - in the day after the Butting One at the point of the northern horn of Taurus:

At the time when Hyadum II was at 0h the corresponding day would have been June 10 (161) - 64 = 97 (APRIL 7), or 97 + 11 = 108 (= 540 / 5) days after the northern winter solstice.

... In China, every year about the beginning of April, certain officials called Sz'hüen used of old to go about the country armed with wooden clappers. Their business was to summon the people and command them to put out every fire. This was the beginning of the season called Han-shih-tsieh, or 'eating of cold food'. For three days all household fires remained extinct as a preparation for the solemn renewal of the fire, which took place on the fifth or sixth day after the winter solstice [Sic!]. The ceremony was performed with great pomp by the same officials who procured the new fire from heaven by reflecting the sun's rays either from a metal mirror or from a crystal on dry moss. Fire thus obtained is called by the Chinese heavenly fire and its use is enjoined in sacrifices: whereas fire elicited by the friction of wood is termed by them earthly fire, and its use is prescribed for cooking and other domestic purposes ... Like archaic China and certain Amero-Indian societies, Europe, until quite recently, celebrated a rite involving the extinguishing and renewal of domestic fires, preceded by fasting and the use of the instruments of darkness. This series of events took place just before Easter, so that the 'darkness' which prevailed in the church during the service of the same name (Tenebrae), could symbolize both the extinguishing of domestic fires and the darkness which covered the earth at the moment of Christ's death. In all Catholic countries it was customary to extinguish the lights in the churches on Easter Eve and then make a new fire sometimes with flint or with the help of a burning-glass. Frazer brings together numerous instances which show that this fire was used to give every house new fire. He quotes a sixteenth-century Latin poem in a contemporary English translation, from which I take the following significant lines: On Easter Eve the fire all is quencht in every place, // And fresh againe from out the flint is fecht with solemne grace. Then Clappers cease, and belles are set againe at libertée, // And herewithall the hungrie times of fasting ended bée ... The 5th or 6th day after the northern winter solstice should be December 26 (360) or December 27 (361). The beginning of April could refer to a date according to some star calendar, and from day 361 to APRIL 1 (91) there were 4 + 91 = 95 days, as if heliacal Canopus had been responsible for not only drinking up all the waters but also for exinguishing all the household fires - i.e. responsible for 3 days of 'eating cold food'. Water and fire were complementary aspects of the same reality. I decided to reverse the style for the dates of Canopus, so that for instance Ga2-1 would correspond to 5 APRIL (95) = June 24 (175) - 80 (as in the day number at 0h) = APRIL 21 (111) - 16 (= 80 - 64):

... The life-force of the earth is water. God moulded the earth with water. Blood too he made out of water. Even in a stone there is this force, for there is moisture in everything. But if Nummo is water, it also produces copper. When the sky is overcast, the sun's rays may be seen materializing on the misty horizon. These rays, excreted by the spirits, are of copper and are light. They are water too, because they uphold the earth's moisture as it rises. The Pair excrete light, because they are also light ... 'The sun's rays,' he went on, 'are fire and the Nummo's excrement. It is the rays which give the sun its strength. It is the Nummo who gives life to this star, for the sun is in some sort a star.' It was difficult to get him to explain what he meant by this obscure statement. The Nazarene made more than one fruitless effort to understand this part of the cosmogony; he could not discover any chink or crack through which to apprehend its meaning. He was moreover confronted with identifications which no European, that is, no average rational European, could admit. He felt himself humiliated, though not disagreeably so, at finding that his informant regarded fire and water as complementary, and not as opposites. The rays of light and heat draw the water up, and also cause it to descend again in the form of rain. That is all to the good. The movement created by this coming and going is a good thing. By means of the rays the Nummo draws out, and gives back the life-force. This movement indeed makes life. The old man realized that he was now at a critical point. If the Nazarene did not understand this business of coming and going, he would not understand anything else. He wanted to say that what made life was not so much force as the movement of forces. He reverted to the idea of a universal shuttle service. 'The rays drink up the little waters of the earth, the shallow pools, making them rise, and then descend again in rain.' Then, leaving aside the question of water, he summed up his argument: 'To draw up and then return what one had drawn - that is the life of the world.'

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||