173. If the C text (and presumably most of the other rongorongo texts too) were presenting myths, stars, dates, and numbers, etc., in an elaborate and intertwined way, then we need to extricate these strands one by one in order to eventually be able to perceive the whole. Number offers hard facts and could therefore be misunderstood as reliable. But they carry very little meaning in themselves and by being universal tools they can be regarded from multiple angles. 325, for instance, could refer to the date of the Julian equinox (3-25), but it could also refer to the year of the Council of Nicaea (AD 325), or be the result of the operation 13 * 25, to mention but a few possibilities. Number 325 could then in principle allude to all such possibilities when it was used or hinted at in the rongorongo texts. The Council of Nicaea - the beginning of a unified new faith - could correspond to March 25 as the date for the Julian equinox which marked the point where winter and summer were unified, like at the dawn of a new day. Glyph 325 in a text could identify a new beginning, where the old and murky was superseded by the new and bright. It could of course also represent e.g. 5 * 65 (which in turn could then lead imagination further ahead to e.g. 365 + 300). Number was an essential part of the description of the beautiful whole, numbers were like the bones in the skeleton structure of the created Cosmos. Therefore we have to take notice of such things as the number of glyphs on side a of the C tablet compared to the number on side b, and to play with these numbers because the creator of the text had probably done so, for instance in making an effort to contrast the contents of the 14 lines on side a with the contents of the 14 lines on the back side of the tablet:

In some way there seems to be a basic difference between side a and side b. This should be the minimum result of our con-templation. We should also react to the fact that side b has not 14 * 29 = 406 but only 348 (= 406 - 2 * 29) glyphs. There is not only a difference between side a and side b but an imbalance.

This should mean the text flow does not continue uninterrupted from the end of side a on to the beginning of side b. Looking at the last glyph on side a we will find an empty hand - the sequence of counting is ending here:

... The way of reckoning on the fingers differs in various islands. In Nengone the fingers are turned up and brought together at five. In the Banks Islands the fingers are turned down. This is often done with the spoken numerals, often without the use of words. The practice of turning down the fingers, contrary to our practice, deserves notice, as perhaps explaining why sometimes savages are reported to be unable to count above four. The European holds up one finger, which he counts, the native counts those that are down and says 'four'. Two fingers held up, the native counting those that are down, calls 'three'; and so on until the white man, holding up five fingers, gives the native none turned down to count. The native is nunplussed, and the enquirer reports that savages can not count above four. The last glyph on side b is similarly drawn without a completed outline, as if the bottom part of the figure had been cut off from view:

... Koti. Kotikoti. To cut with scissors (since this is an old word and scissors do not seem to have existed, it must mean something of the kind). Vanaga. Kotikoti. To tear; kokoti, to cut, to chop, to hew, to cleave, to assassinate, to amputate, to scar, to notch, to carve, to use a knife, to cut off, to lop, to gash, to mow, to saw; kokotiga kore, indivisible; kokotihaga, cutting, gash furrow. P Pau.: koti, to chop. Mgv.: kotikoti, to cut, to cut into bands or slices; kokoti, to cut, to saw; akakotikoti, a ray, a streak, a stripe, to make bars. Mq.: koti, oti, to cut, to divide. Ta.: oóti, to cut, to carve; otióti, to cut fine. Churchill. Pau.: Koti, to gush, to spout. Ta.: oti, to rebound, to fall back. Kotika, cape, headland. Ta.: otiá, boundary, limit. Churchill. Thus we could not expect the sum of the number of glyphs on the tablet to carry much meaning - it was not necessary to continue counting beyond 392 respectively beyond 348. The Tahua (A) tablet, on the other hand, was surely constructed for the counting to continue all the way from the beginning to the end of the text:

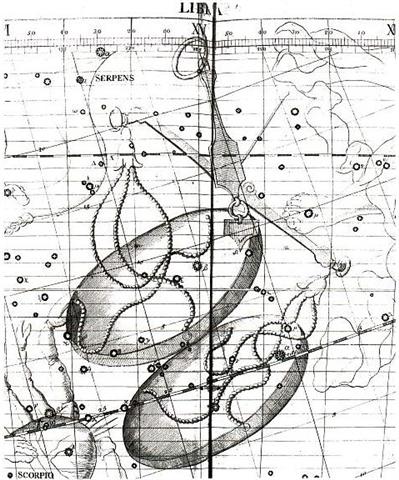

En passent we should take notice of the fact that a beginning, after what could be a pair of lunar synodic months (2 * 29½ = 59 days), was described by Metoro as resembling (the point of) a 'tattoing instrument' (hoea). ... In the morning of the world, there was nothing but water. The Loon was calling, and the old man who at that time bore the Raven's name, Nangkilstlas, asked her why. 'The gods are homeless', the Loon replied. 'I'll see to it', said the old man, without moving from the fire in his house on the floor of the sea. Then as the old man continued to lie by his fire, the Raven flew over the sea. The clouds broke. He flew upward, drove his beak into the sky and scrambled over the rim to the upper world. There he discovered a town, and in one of the houses a woman had just given birth ... We can compare with the beginning of side a on the C tablet and also with the upside down figure in position 370, which 'happens to' coincide with the result of the operation (392 + 348) / 2:

And early on side b there was a 3rd and final place which Metoro referred to as hoea - but without the qualifying suffix te:

Possibly we should understand that Metoro meant this was a point without the negative tê he might have been using on side a. The documentation which Bishop Jaussen saved for the future has no diacritic marks (with a very few exceptions such as haú). The Tahua text has 580 glyphs before the 'red gills of dawn' (vaha mea).

Although there is an empty hand at the end of side a the basic time count evidently continues, because 392 + 21 = 413, which number we immediately will recognize as 14 lunar synodic months. 7 * 59 = 413 = 740 - 327 and beyond this 'fish-hook point' came the birth of a new cycle:

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||