My sudden insight that the

henua type of glyph (GD37) probably has as its

origin the fact that trees all over the world marked

time not only by illustrating the seasons through their

visible changes (flowering, leaves budding, fruits

ripening, leaves being dropped etc), but also - more

subtly - by some

species being picked out as seasonal markers regularly

located over the year (e.g. 13 kinds of trees each

'governing' 28 days), may explain the occurences of e.g.

these types of glyphs:

|

|

|

|

Ab6-42 |

Ab4-23 |

Aa7-74 |

|

|

|

|

Qb6-128 |

Kb3-15 |

Eb3-19 |

Metoro normally

said henua when referring to GD37 glyphs. That

word does not mean 'tree' or 'wood', but is an

expression which describes what the GD37 glyph

symbolized, viz. the 'land' (which changes in its cycles

over the year):

| Henua Land, ground, country; te tagata noho i ruga i te henua the

people living on the earth. Placenta: henua o te poki. Vanaga.

1. Land, country, region; henua tumu, native land. 2. Uterus. 3.

Pupuhi henua, volley. Churchill.

M.: Whenua, the Earth; the whole earth: I pouri

tonu te rangi me te whenua i mua. 2. A country or district: A e

tupu tonu mai nei ano i te pari o taua whenua. Tangata-whenua,

natives of a particular locality: Ko nga tangata-whenua ake ano o

tenei motu. Cf. ewe, the land of one's birth. 3. The

afterbirth, or placenta: Ka taka te whenua o te tamaiti ki te moana.

Cf. ewe, the placenta. 4. The ground, the soil: Na

takoto ana i raro i te whenua, kua mate. 5. The land, as opposed to

the water: Kia ngaro te tuapae whenua; a, ngaro rawa, ka tahi ka

tukua te punga. Text Centre. |

We have here an example

showing that Metoro might have 'translated' the

rongorongo glyphs not by explaining the picture but

by explaining what the picture meant. We must remember

that.

At the start of the X-area

we do not find henua (Gd37) but niu

(GD18), although much points at these niu glyphs

are standing at the exact beginning of the new year:

|

|

|

Aa1-13 |

Pa5-67 |

How may that be explained?

Is a picture of a tree too trivial? The halo around the

head of a holy 'person' would be difficult to picture in

a rongorongo glyph (because such glyphs show only

outlines). Radiating light in all directions would be

easier drawn (as in niu).

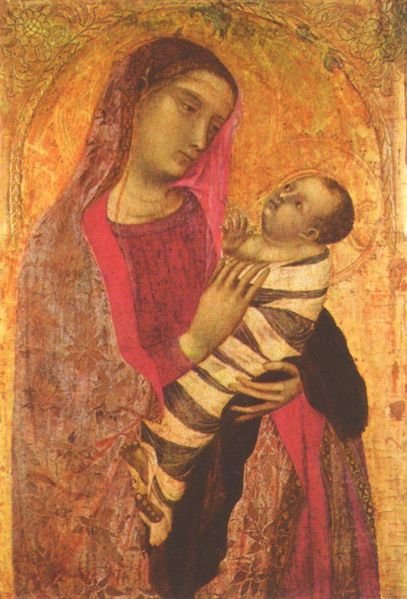

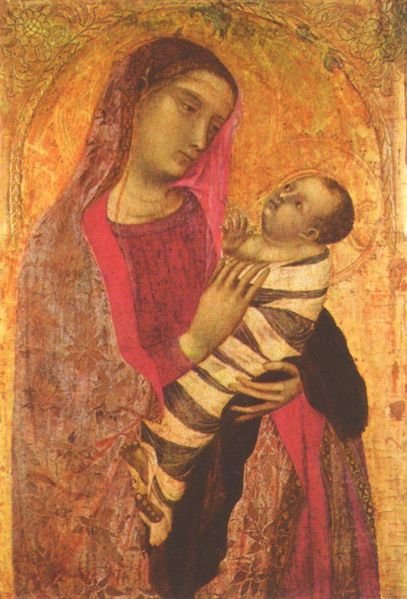

The picture

is from Wikipedia: 'Madonna and Child' by Ambrogio

Lorenzetti. I searched for 'swaddling', with the idea

that I would find some picture of how Polynesians

swaddled their newborn babies. However I did not find

any such information.

Newborn

babies do not show their arms and legs, because they

have been swaddled. That could explain the shape of

Pa5-70 (and similar glyphs):

"The child has hardly

left the mother's womb, it has hardly

begun to move and stretch its limbs,

when it is given new bonds. It is

wrapped in swaddling bands, laid down

with its head fixed, its legs stretched

out, and its arms by its sides; it is

wound round with linen and bandages of

all sorts so that it cannot move …

Whence comes this

unreasonable custom? From an unnatural

practice. Since mothers despise their

primary duty and do not wish to nurse

their own children, they have had to

entrust them to mercenary women. These

women thus become mothers to a

stranger's children, who by nature mean

so little to them that they seek only to

spare themselves trouble. A child

unswaddled would need constant watching;

well swaddled it is cast into a corner

and its cries are ignored …

It is claimed that

infants left free would assume faulty

positions and make movements which might

injure the proper development of their

limbs. This is one of the vain

rationalizations of our false wisdom

which experience has never confirmed.

Out of the multitude of children who

grow up with the full use of their limbs

among nations wiser than ourselves, you

never find one who hurts himself or

maims himself; their movements are too

feeble to be dangerous, and when they

assume an injurious position, pain warns

them to change it." (Wikipedia citing

Jean Jacques Rousseau - Emile: Or, On

Education, 1762.)

Barthel

suggested that 'no-legs-visible' might

indicate 'a god' (gods do not

need to move):

"Für das Zeichen 290,

[the type of glyph which I have here

exemplified by Hb8-136 - maybe 'a

swaddled person' with winglike arms]

das den

Götternamen 'mata viri' bzw. 'ruanuku'

vorangeht, wurde die Lesart 'atua' noch in

weiteren Textzusammenhängen geprüft."

"Im

Tafeltext Gr5 folgen die Zeichen 20 [he means the right

part of Ga5-10] und 79 [Ga5-11] als 'mata -

viri' aufeinander. Es liegt nahe, das vorangehende

Zeichen 290 [the left part of Ga5-10] als 'atua'

zu deuten. Zeichen 290, mit seinem massigen Leib und den

fehlenden Beinen, könnte möglicherweise ein Idol aus

Stein oder Holz darstellen und den Begriff der Gottheit

symolisierien."

|

|

|

- |

|

|

|

|

|

Ga5-10 |

Ga5-11 |

Ga5-12 |

Ga5-13 |

Ga5-14 |

Ga5-15 |

Ga5-16 |

|

|

|

|

|

... |

|

Kb1-12 |

Kb1-13 |

Kb1-14 |

Kb1-15 |

Kb1-16 |

As to

ruanuku he refers to Ab6-82:

|

|

|

|

|

|

Ab6-76 |

Ab6-77 |

Ab6-78 |

Ab6-79 |

Ab6-80 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Ab6-81 |

Ab6-82 |

Ab6-83 |

Ab6-84 |

Ab6-85 |

Neither of these two examples

convinces me that we should read atua (mata

viri respectively ruanuku). Ga5-10--16

(and the parallel text in K) has as its subject

matter the

period when sun turns around at midsummer and

the right part of Ab6-82 may symbolize the 'double

faces' as seen in Ab6-47 and Ab6-54 (possibly Mars

respectively Venus).

Though of course Barthel may

still be right - given that there are gods representing

midsummer respectively the double 'faces' of Mars /

Venus.

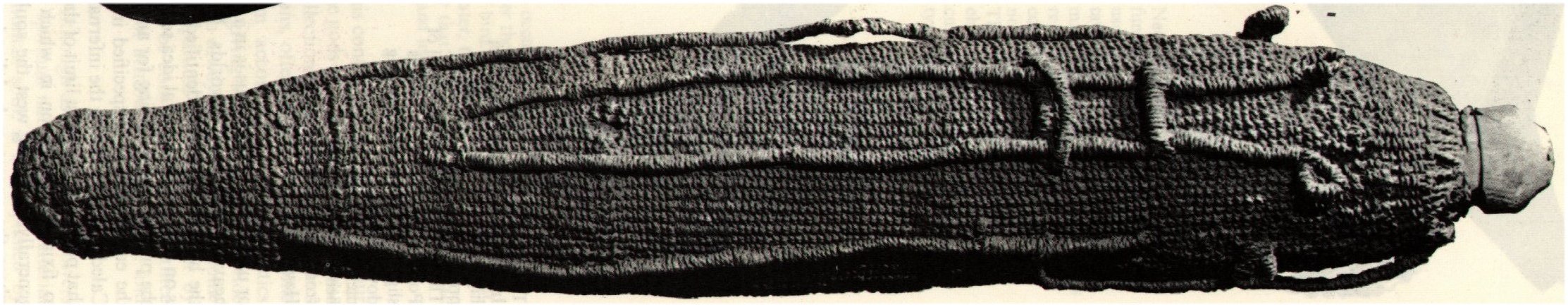

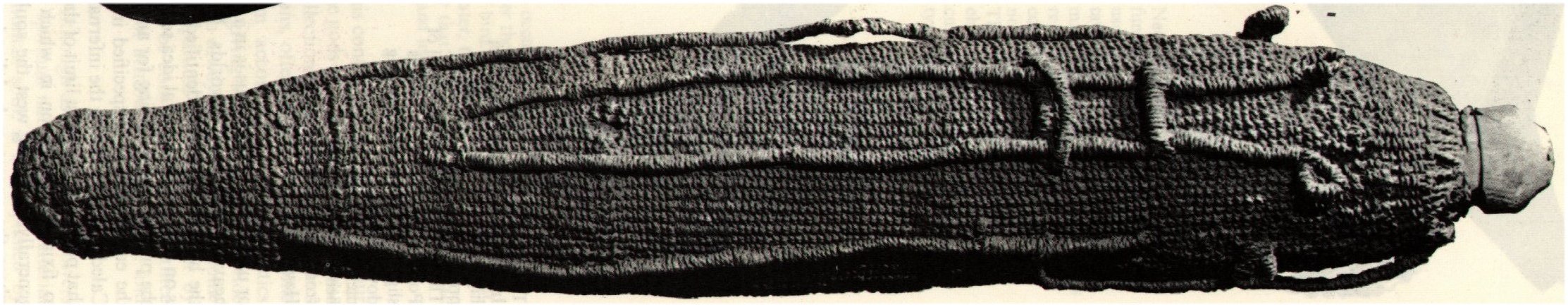

'No legs' may also be a way of making

threatening 'persons' harmless. In ancient times

they used to bury (dead) people with legs and arms

immobilized by ropes. Which reminds me of an image

of

'Oro (a war god):

"The war god Oro. Oro was worshipped

all over Polynesia, but in Tahiti not represented by

a carved human figure. Instead he was a bundle tied

up with cords over a wooden core; limbs and facial

features can, however, be recognized. Pleaded sinnet

cloth on wood. Tahiti." (Larousse)

"Vermutlich können in der

Osterinselschrift unter den Vorkommen von Zeichen

290 noch weitere Götternamen ausfindig gemacht

werden. Auch das Zeichen 1 [i.e. henua, GD37]

in seiner begrifflich verwandten Rolle kann hierfür

als nützlich gelten. Mit 'toko'

wurden auf Neu-Seeland die holzgeschnitxten

Götterstäbe, auf Tahiti pfostenartige Figuren der

groβen Gottheiten

bezeichnet. An diese übertragene Bedeutung sollte

man bei der Beurteilung des Stabzeichens denken. In

den Tafeltexten scheint jedenfalls das Zeichen 1 an

einigen Stellen direkt für das Zeichen 290 eintreten

zu können, d.h. 'toko' für 'atua'

gesetzt worden zu sein."

He gives no

examples, though, of where in the rongorongo

texts his number 1 is equivalent to his number 290,

and I cannot remember any parallel texts by means of

which this conclusion may be drawn.