"Ogotemmêli had his

own ideas about calculation. The Dogon in fact did use the

decimal system, because from the beginning they had counted on

their fingers, but the basis of their reckoning had been the

number eight and this number recurred in what they called in

French la centaine, which for them meant eighty. Eighty

was the limit of reckoning, after which a new series began.

Nowadays there could be ten such series, so that the European

1,000 corresponded to the Dogon 800.

But Ogotemmêli

believed that in the beginning men counted by eights - the

number of cowries on each hand, that they had used their ten

fingers to arrive at eighty, but that the number eight appeared

again in order to produce 640 (8 x 10 x 8). 'Six hundred and

forty', he said, 'is the end of the reckoning.' According to

him, 640 covenant-stones had been thrown up by the seventh Nummo

to make the outline in the grave of Lébé.

So the cowries that

the father of the first twins found in the ground when

harvesting millet after the second sowing, were a foreshadowing

of commerce ..."

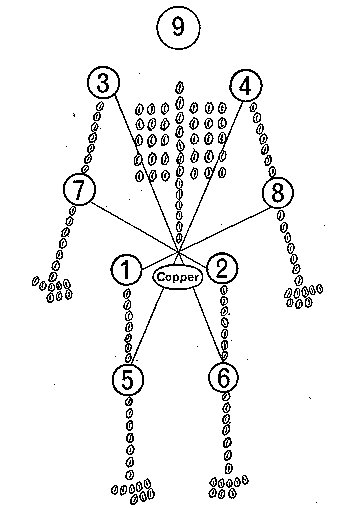

I

can count to 131 cowries in this picture of Lébé. 4 * 8 = 32

cowries form the hands and feet. Each limb (arm, leg) has 2 * 7

= 14 cowries. If we add the cowries for hands and feet the number will be 4

* 22 = 88. The central spinal column is marked by 13 cowries and

it is responsible for '1 more'. Otherwise we would have had 88 +

12 = 100 (respectively 130). The rib cage is formed by 18 + 12 = 30 cowries.

The head of Lébé is missing, or maybe it is represented by the

highest cowrie of the spine. The cowries are drawn not very

different from the 'balls' of maitaki:

After this preliminary - in order to bring some perspective on how

a

one-dimensional sequence of numbers can form patterns (like

kaikai strings) - let us move on to the

two-dimensional area of a field:

"Above the door of

the temple is depicted a chequer-board of white squares

alternating with squares the colour of the mud wall. There

should strictly be eight rows, one for each ancestor.

This chequer-board

is pre-eminently the symbol of the 'things of this world' and

especially of the structure and basic objects of human

organization. It symbolizes: the pall which covers the dead,

with its eight strips of black and white squares representing

the multiplication of the eight of human families; the façade of

the large house with its eighty niches, home of the ancestors;

the cultivated fields, patterned like the pall; the villages

with streets like seams, and more generally all regions

inhabited, cleared or exploited by men. The chequer-board and

the covering both portray the eight ancestors." (Ogotemmêli)

Life down on earth is like the light on Moon, it alternates

between two 'faces' (growing and decaying). The 'squares' of the

'gameboard of life' alternates in a cyclic and regular pattern.

Moving on from Moon, who governs the horizontal fields down

on earth, we must move in the vertical dimension in order to

reach Sun. Let us once again (cfr at honu) consider this gameboard (for Chinese

checkers):

The 6 coloured triangular 'mountains' around the white

hexagon field, when merged together become white. Colours are

generated from white and white is also the end of the colours.

Colours can be seen

only in daytime. There are 1 + 2 + 3 + 4 = 10 coloured

marbles in

each of these 6 triangles. But counting the white holes

(corresponding to nighttime)

we will find 6 * 10 + 1 hole. The central hole in the white hexagon

represents 'one more' and is necessary for moving the little

balls.

At the beginning of the game no hole is located in any of the

'mountains' - they have no room for 'life'. They are like the

clenched fists of the season of straw.

6

* 10 + 1 = 61 is the total number of white holes in the hexagon, which can be imagined as waiting for the 'turning in'

(at the horizon in the west) of the

'coloured marbles'. Yet a single hole is left empty (maybe

waiting for the head of Lébé):

If we reduce the size of the Chinese gameboard, the next smaller size

will have 6 * 6 + 1 = 37 holes. Reducing the size once again will bring us

down to

6 * 3 + 1 = 19 holes. We can recognize the connection

with the Sun numbers 18, 36, and 60, as if once man used to count

pebbles (or cowries) in triangular patterns to measure Sun.

These Sun numbers are 'eternal' and not

involved in the cycles of change ('life'). In order to create

life (increase by 'one more') holes must be filled.

The smallest possible game board of this sort is 6 * 1 + 1

= 7, because with next reduction we will reach 6 * 0 + 1 = 1 and

we can no longer recognize the triangular form. This last step in reduction

leads us, so to say, to the hole of 'one more'. In the beginning there is no

form.

If we return upwards in size, and add the steadily

growing gameboards together (forming a pyramid with a hexagonal

base and with a little hole at the apex going all the way down), we will get the following series: 1 + 7 = 8,

1 + 7 + 19 = 27, 1 + 7 + 19 + 37 = 64, 1 + 7 + 19 + 37 + 61 =

125, ...

In other words we will reach the cubic numbers: 1 = 1 * 1 * 1, 8 = 2

* 2 * 2, 27 = 3 * 3 * 3, 64 = 4 * 4 * 4, 125 = 5 * 5 * 5, ...

Moving up from a hexagonal field we will reach a cube.

The cube reflects the hexagonal gameboard of Chinese

checkers. This is, as I believe, what is meant by 'squaring' when the

'circle' is the path of

Sun over the year.

If you look at a cube you can only see half of its sides. Each

such side can be divided in two triangular areas. What you see

is similar in form to the Chinese gameboard. The central hole

corresponds to the position of the closest cube corner. The back

side of the cube represents the underside of the gameboard.

The cube is the form of Saturn (the last 'planetary garment' in

the Sun cycle). He should be counted as 5 * 5 * 5 = 125 (12 and

'fire'). 365 - 125 = 240 = 8 * 30.