|

TRANSLATIONS

Next pages with underpages:

|

4.

Here I could have ended my 'preliminary remarks and

imaginations'. Rona glyphs should, I have suggested, appear

immediately 'inside' the beginning of a new season or cycle, and the

twisted body posture ought to represent how 'movement' from now on

goes in the other direction. This is enough to try out, for instance

by looking at the beginning of texts after the tablets have been

turned, e.g. represented by our wellknown pair Gb1-6--7:

I have not classified them as rona, but Gb1-13

(in position 242 + 1) is a rona glyph.

However (a strange word which English Etymology does not care to

explain), my ambition goes higher. In the preceding hupee

chapter we have made a first (and fairly successful I would say)

attempt at connecting the geography of Easter Island with the

'geography in the sky' and we ought to go on in that direction.

Rona glyphs seem to be promising.

In the following pages, not so few, I will try to arrange my ideas

in as good an order as I can, but I know there is no King's way

ahead. The terrain is difficult. So let's go:

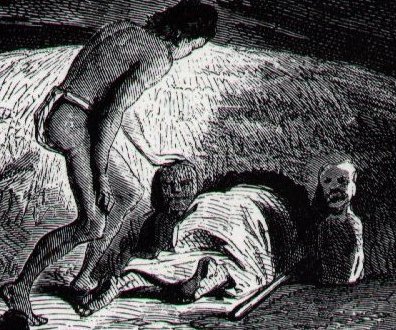

The entrance

to a hare paega can be protected by 2 rona

figures, or rather a Rona and a Runu I guess:

Not much is visible of them in this picture (cut out

from a drawing by Pierre Loti - cfr at haú) but they are standing there and in between

someone is crawling inside through the door opening.

The door should be at a cardinal point, one of the corners of the

'square earth'. If so, then the location ought to be at equinox I

imagine, because only the gods should enter a canoe at the stern or the prow

(and a hare paega is the equivalent of an overturned

canoe, the 'night side' of a canoe):

... to enter a war

canoe from either the stern or the prow was equivalent to a 'change

of state' or 'death'. Instead, the warrior had to cross the

threshold of the side-strakes as a ritual entry into the body of his

ancestor as represented by the canoe ...

Métraux has mentioned these entrance figures:

"The low entrances of

houses were guarded by images of wood or of bark cloth, representing

lizards or rarely crayfish.

The bark cloth

images were made over frames of reed, and were called manu-uru,

a name given also to kites, masks, and masked people

..."

The lizard (moko) and the crayfish (ura) form a pair

of contrasts, one up on land and the other down in the sea.

Manu-uru

are not real 'birds', just imitations

(reflections) made of 'straw'. Metoro

said toa tauuru

for 7 of the periods of the night (cfr Aa1-37--46). In my

added item for uru in the Polynesian dictionary I have commented that

uru

usually means breadfruit (= 'skull') and that its fruit resembles a

human skull. A cranium and uru symbolize, I think, the end of

life - which has great nutritional value. Uru has 2 u,

as is should for a 'back wheel'.

Nightfall and morning connect the diurnal

cycle with the yearly cycle. The hour of midnight was preferably a

time for sleep, because at that time (equal to new year) there was a

'door' open through which figures of fancy and fear moved.

Métraux has given us a good description of how it was to sleep in a

hare paega:

"... The most vivid

description of hut interiors is given by Eyraud ... who slept in

them several nights:

Imagine a half open

mussel, resting on the edge of its valves and you will have an idea

of the form of that cabin. Some sticks covered with straw form its

frame and roof. An oven-like opening allows its inhabitants to go

inside as well as the visitors who have to creep not only on all

fours but on their stomachs.

This indicates the

center of the building and lets enter enough light to see when you

have been inside for a while. You have no idea how many Kanacs may

find shelter under that thatch roof. It is rather hot inside, if you

make abstraction of the little disagreements caused by the deficient

cleanliness of the natives and the community of goods which

inevitably introduces itself ...

But by night time, when

you do not find other refuge, you are forced to do as others do.

Then everybody takes his place, the position being indicated to each

by the nature of the spot. The door, being in the center, determines

an axis which divides the hut into two equal parts. The heads,

facing each other on each side of that axis, allow enough room

between them to let pass those who enter or go out. So they lie

breadthwise, as commodiously as possible, and try to sleep."

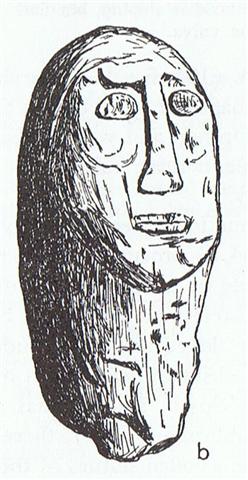

Métraux has also given us a close-up picture of one of these

manu-uru figures:

"The nose is narrow and

straight and on the same plane as the forehead. The mouth is formed

by two parallel raised strips. The oval eyes protrude. The

cheekbones are two crescentic prominences ..."

|

|

5.

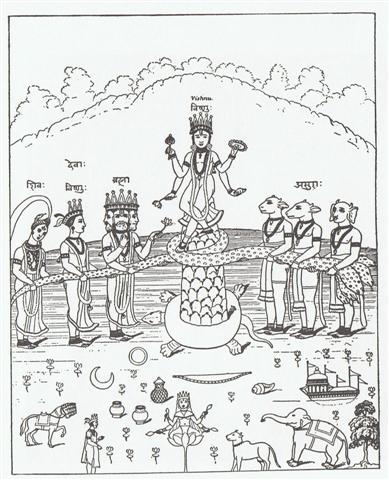

In the Tuamotuan dialect

ronarona

means 'to pull one another about'. On

Easter Island rona means 'drawing, traction'.

Nga

Tavake A Te Rona and

Te Ohiro A Te Runu - the pair who were on the island

already before Ira and his team anchored (like gods in the

solstice

bay, Hanga Te Pau) - could represent the 2

forces ('beasts' contra 'men and gods') constantly tugging at war

and

beautifully illustrated in India:

The beasts are in

spring, and they describe the raw rava force, while

men and gods are more restrained, with mature planning ahead rather

than shortsighted and childish focus on the present only.

I have not earlier given an adequate description of

the rava force, because a separate

page was needed.

Te Ohiro A Te Runu should correspond to the team of autumn,

or

the team of Moon we could say, because Ohiro is the 1st

night of the Moon. And Nga Tavake A Te Rona would then

correspond to the team of spring, the team of Sun. However, it is

not so easy.

|

|

Let us begin by repeating what Vanaga says:

1. Enough, sufficient; ku-rava-á,

that's enough, it is sufficient. 2. To be satiated, to be satisfied;

ku rava-á te tagata i te kai,

the man has eaten his fill. 3. Used very commonly before verbs to

express someone much inclined towards this action:

tagata rava taûa, quarrelsome person;

rava kai, glutton;

rava haúru, sleepy-head;

rava kî, chatterbox;

rava tagi, cry-baby;

rava keukeu, hard-working;

vara is often used instead of

rava. Vanaga.

Rava is here given two main meanings, as I

understand it. First of all an intensive, focused, selfish mood, and

secondarily the result thereof, viz. enough! The primary sense must be the

aggressive mood - hunger in all its senses - what can be expected after

a winter

season with scarce resources. |

|

Next we should compare with the not quite so intense

and more neutral rave:

Ta.: Rave, to take. Sa.: lavea, to be

removed, of a disease. To.: lavea, to bite, to take the hook,

as a fish. Fu.: lave, to comprehend, to seize. Niuē:

laveaki, to convey. Rar.:

rave, to take, to

receive. Mgv: rave, to

take, to take hold; raveika,

fisherman. Ma.: rawe, to

take up, to snatch. Ha.: lawe,

to take and carry in the hand. Mq.: ave,

an expression used when the fishing line is caught in the stones.

Churchill 2.

Behind this spectrum of

meanings we can discern the idea of 'seize' (to take possession of). In the intensive hungry

rava mood much forceful

action (rave) must come, must be the result of the primary

drives. No time to deliberate or discuss, hunger is ravenous. But

rave

has no childish tune, it is a calculating and mature 'beast' who is

acting. |

In Churchill there is much information regarding rava,

and we can see that there is no clear bordeline between rava

and rave:

1. [I have missed to

copy this page in Churchill.] 2. To get, to have, to conquer, to

gain, to obtain, invasion, to capture, to procure, to recover,

to retrieve, to find, to bring back, to profit, to assist, to

participate, to prosper; mea

meitaki ka rava, to deserve. PS Pau.:

rave, to take. Mgv.:

rave, to take, to

acquire possession. Ta.: rave,

to seize, to receive, to take. To.:

lava, to achieve, to obtain. Viti:

rawā, to obtain, to

accomplish ... 3. To know; rava iu, to discern. 4.

Large; hakarava, to enlarge, to augment, to add. PS Sa.:

lava, large, very. 5. Hakarava, wide, width,

across, to put across, yard of a ship, firm; hakarava

hakaturu, quadrangular. P Mgv.: ravatua, the shelving

ridge of a road, poles in a thatch roof, a ridge. In the

Tongafiti speech this appears only in Maori whakarawa to

fasten with a latch of bolt ... 6. A prepositive intensive;

rava oho, to take root; rava keukeu, to apply

oneself; rava ahere, agile, without fixed abode; rava

ki, to prattle; rava vanaga, to prate. Mq.: ava,

enough, sufficient. 7. Hakarava, gummy eyes, lippitude.

8. Hakarava omua to come before, precede.

He then continues with words incorporating

rava:

Ravagei, to

prattle. Ravahaga, capture. Ravaika, to fish.

Mgv.: raveika, a fisherman. Mq.: avaika, avaiá,

id. Ravakai (ravekai), glutton, insatiable; tae

ravekai, frugal. Ravakata (ravakakata),

jovial, merry. Ravaki, to prattle, to tell stories,

loquacious, narrator, orator, eloquent, to boast, to speak evil,

to defame, slander, gossip. Ravapeto, to blab, to speak

evil. Ravapure, fervent, earnest. Ravavae,

invention. Ravatere, to scare away. Neku

ravatotouti, agile. Ravavanaga, loquacious,

garrulous, to tell stories, narration.

A negative tense is colouring many of these items

(glutton, boast, speak evil, blab etc). Table manners are not high

in priority when you are ravenous, and in a competition for scarce

resources the noble side is put aside. Furthermore childish

behaviour comes to the surface in times of stress.

A special case is the double variant of rave:

Ta.: raverave, a

servant, to serve. Ha.: lawelawe, to wait on the table,

to serve. Churchill.

When the gods and men of equal rank have sat down

to take what they want the more humble men should stand aside as

servants, they are the Mercury characters. |

|

Fornander is as always a good source for coming to

grips with the meanings of words, and he has recognized the

relationship between rava and rave. First rava

(lawa):

LAWA, v. Haw., to work out, even to the

edge or boundary of a land, i.e., leave none uncultivated, to

fill, suffice, be enough.

Sam.,

lava, be enough, to complete; adj., indeed, very. Tah.,

rava-i, to suffice. N. Zeal., rava-kore, lit. 'not full',

poor. Fiji., rawa, accomplish, obtain, possess.

Sanskr.,

labh, lambh, to obtain, get, acquire, enjoy, undergo,

peform; lábha, acquisition, gain; rabh, to seize, to

take.

Lith.,

loba, the work of each day, gain, labour; lobis, goods,

possessions; pra-lobti, become rich; api-lobe, after

work, i.e., evening.

A. Pictet

refers the Lat. labor, work, to this same family, as well as

the Irish lobhar and the Welsh llafur. He also, with

Bopp and Benfey, refers the Goth. arbaiths, labour, work, to

the Sanskr. rabh = arb, as well as the Anc. Slav.,

rabu, a servant. Russ., rabota, labour. Gael., airbhe,

gain, profit, product.

The modern word 'robot' combines the

meanings 'work' and 'servant'. One cannot avoid thinking about the

'slaves' who do the work and those who take the profit. The division

between rava and raverave is still in force, and it

was also at the base of the Greek culture. Without work

there will be no food, but the food can be taken (robbed) by someone

tough enough higher up. |

|

And lawe:

LAWE,

v.

Haw., to carry, bear, take from out of; lawe-lawe, to wait upon, to

attend on, serve, to handle, to feel of; adj. pertaining to

work.

Tah.,

rave, to receive, to take, seize, lay hold of; s. work,

operation; rave-rave, a servant, attendant.

Rarot.,

Paum., rave, id. Sam., lave, to be of service;

lave-a, to be removed, of a disease; lavea'i, to

extricate, to deliver. Fiji., lave, to raise, lift up.

Malg.,

ma-lafa, to take, seize; rava, pillage, destruction.

Sunda., rampok, theft. Mal., rampas, me-rabut,

take forcibly. Motu (N. Guinea), law-haia, to take away ...

Greek,

λαμβανω, έλαβον,

take hold of, seize, receive, obtain; λημμα,

income, gain; λαβη,

λαβις, grip, handle.

Lat.,

labor,

work, activity; perhaps also Laverna,

the goddess of gain or profit, the protectress of thieves;

rapio,

rapax.

Goth.,

raupjan, to

reap, pluck; raubon,

to reave, rob. Sax., reafian,

take violently. Pers., raftan,

to sweep, clean up; robodan,

to rob. Lith., ruba,

pillage; rûbina,

thief.

The Fijian word

lave, to raise, lift up, can by

association go on to reva. But basically there is

no resemblance between raising food or else to superiors (rave)

on one hand and lifting up high in order to suspend (reva).

|

|

Tavake in Nga Tavake a Te Rona could refer to the name

of one of the tropic birds:

"Tavake is the

general Polynesian name for the tropic bird, whose red tail feathers

were very popular. This name is closely connected with the original

population." (Barthel 2)

"The Red-tailed

Tropicbird, Phaethon rubricauda, is a seabird that nests

across the Indian and Pacific Oceans. It is the rarest of the

tropicbirds, yet is still a widespread bird that is not considered

threatened. It nests in colonies on oceanic islands.

The Red-tailed

Tropicbird looks like a stout tern, and hence closely resembles the

other two tropicbird species. It has generally white plumage, often

with a pink tinge, a black crescent around the eye and a thin red

tail feather. It has a bright red bill and black feet

...

When breeding they

mainly choose coral atolls with low shrubs, nesting underneath them

(or occasionally in limestone cavities). They feed offshore away

from land, singly rather than in flocks. They are plunge-divers that

feed on fish, mostly flying fish, and squid."

(Wikipedia)

Nga marks plural:

| Ga

Preposed plural marker of rare usage. 1.

Sometimes used with a few nouns denoting human beings,

more often omitted. Te ga vî'e, te ga poki, the

women and the children. Ga rauhiva twins. 2. Used

with some proper names. Ga Vaka, Alpha and Beta

Centauri (lit. Canoes). Vanaga. |

It seems impossible to connect plural with

Spring Sun, he has only one 'leg' and spring is singleminded. Nga Tavake must belong beyond

midsummer. And this seems to agree with where Ira found him:

"Through the

meeting with Nga Tavake, the representative of the

original population in the area north of Rano Kau, the

number of the explorers is once again complete. Not only are

Kuukuu and Nga Tavake related as 'loss' and 'gain',

but also they share the same economic function: it was Kuukuu's

special mission to establish a yam plantation after the landing

(in his role he represents the vital function of the good

planter); Nga Tavake joined the explorers to work with

them in the yam plantation of the dead Kuukuu (i.e., he

closes the gap caused by the death of Kuukuu among the

planters.)" (Barthel 2)

Nga Tavake A Te Rona was found at the

back side of the island, the side of the Moon. The important

feature of the bird was its thin red tail feather. Red at the

end suggest a fire at the end of a cycle.

|

|

"... They all sat down

and rested [on the plain of

Oromanga],

when suddenly they saw that a turtle had reached the shore and had

crawled up on the beach. He [Ira] looked at it and said,

'Hey, you! The turtle has come on land!' He said, 'Let's go! Let's

go back to the shore.' They all went to pick up the turtle. Ira

was the first one to try to lift the turtle - but she didn't move.

Then Raparenga

said, 'You do not have the necessary ability. Get out of my way so

that I can have a try!' Raparenga stepped up and tried to

lift the turtle - but Raparenga could not move her. Now you

spoke, Kuukuu: 'You don't have the necessary ability, but I

shall move this turtle. Get out of my way!' Kuukuu stepped

up, picked up the turtle, using all his strength. After he had

lifted the turtle a little bit, he pushed her up farther.

No sooner had he pushed

her up and lifted her completely off the ground when she struck

Kuukuu with one fin. She struck downward and broke Kuukuu's

spine. The turtle got up, went back into the (sea) water, and swam

away. All the kinsmen spoke to you (i.e. Kuukuu): 'Even you

did not prevail against the turtle!'

They put the injured

Kuukuu on a stretcher and carried him inland. They prepared a

soft bed for him in the cave and let him rest there. They stayed

there, rested, and lamented the severely injured Kuukuu.

Kuukuu said, 'Promise me, my friends, that you will not abandon

me!' They all replied, 'We could never abandon you!' They stayed

there twenty-seven days in Oromanga. Everytime Kuukuu

asked, 'Where are you, friends?' they immediately replied in one

voice, 'Here we are!'

They all sat down and

thought. They had an idea and Ira spoke, 'Hey, you! Bring the

round stones (from the shore) and pile them into six heaps of

stones!' One of the youths said to Ira, 'Why do we want heaps

of stone?' Ira replied, 'So that we can all ask the stones to

do something.' They took (the material) for the stone heaps (pipi

horeko) and piled up six heaps of stone at the outer edge of the

cave.

Then they all said to

the stone heaps, 'Whenever he calls, whenever he calls for us, let

your voices rush (to him) instead of the six (of us) (i.e., the six

stone heaps are supposed to be substitutes for the youths). They all

drew back to profit (from the deception) (? ki honui) and

listened. A short while later, Kuukuu called. As soon as he

had asked, 'Where are you?' the voices of the stone heaps replied,

'Here we are!' All (the youths) said, 'Hey, you! That was well

done!' ..." (Manuscript E according to Barthel 2)

|

|

As regards

Te Ohiro A Te Runu (who had died - maybe killed by a turtle like

Kuukuu?) we must first consider

runu:

|

Runu

To take, to grab with the hand; to

receive, to welcome someone in one's home. Ko Timoteo

Pakarati ku-runu-rivariva-á ki a au i toona hare,

Timoteo Pakarati received me well in his house.

Runurunu, iterative of runu: to take

continuously, to collect. Vanaga.

1. To pluck, to pick, a burden. 2. A

substitute; runurunu, a representative.

Churchill. |

The idea of 'to take' (rave) corresponds to spring rather

than to autumn, to the front side rather than to the back side. In

order 'to

grab with the hand' (runu) it is certainly necessary to have

a hand (rima), which ought to exclude the nuku

(autumn) season. Furthermore, ru in the Mangarevan dialect

means 'eager, in haste, impatient', which is a feeling of spring

rather than autumn.

Then we must also take into consideration the possible meanings of hiro:

| Hiro

1. A deity invoked when praying for rain

(meaning uncertain). 2. To twine tree fibres (hauhau,

mahute) into strings or ropes.

Ohirohiro, waterspout

(more exactly pú ohirohiro), a column of water

which rises spinning on itself.

Vanaga.

To spin, to twist. P Mgv.: hiro,

iro, to make a cord or line in the native manner

by twisting on the thigh. Mq.: fió, hió,

to spin, to twist, to twine. Ta.: hiro, to twist.

This differs essentially from the in-and-out movement

involved in hiri 2, for here the movement is that

of rolling on the axis of length, the result is that of

spinning. Starting with the coir fiber, the first

operation is to roll (hiro) by the palm of the

hand upon the thigh, which lies coveniently exposed in

the crosslegged sedentary posture, two or three threads

into a cord; next to plait (hiri) three or other

odd number of such cords into sennit. Hirohiro,

to mix, to blend, to dissolve, to infuse, to inject, to

season, to streak with several colors; hirohiro ei

paatai, to salt. Hirohiroa, to mingle;

hirohiroa ei vai, diluted with water. Churchill.

Ta.: Hiro, to exaggerate. Ha.:

hilohilo, to lengthen a speech by mentioning

little circumstances, to make nice oratorial language.

Churchill. |

The deity of sneak thieves was

Whiro (Mercury) on New Zealand (according to Makemson):

|

Hawaiian Islands |

Society Islands |

Tuamotus |

New Zealand |

Pukapuka |

|

Ukali

or

Ukali-alii

'Following-the-chief' (i.e. the Sun)

Kawela 'Radiant' |

Ta'ero

or

Ta'ero-arii

'Royal-inebriate' (referring to the eccentric and

undignified behavior of the planet as it zigzags

from one side of the Sun to the other) |

Fatu-ngarue

'Weave-to-and-fro'

Fatu-nga-rue

'Lord of

the Earthquake' |

Whiro

'Steals-off-and-hides'; also the universal name for

the 'dark of the Moon' or the first day of the lunar

month; also the deity of

sneak thieves and rascals. |

Te Mata-pili-loa-ki-te-la

'Star-very-close-to-the-Sun' |

Irregular movement is a basic astronomical characteristic of Mercury,

which explains the action 'to-and-fro'. Whiro

was a deity of thieves, because they must be quick in their

actions. In spring it must go quick, in

autumn it can take time. There is nothing

negative with theft, according to

the Polynesians view, on the contrary it is a virtue.

|

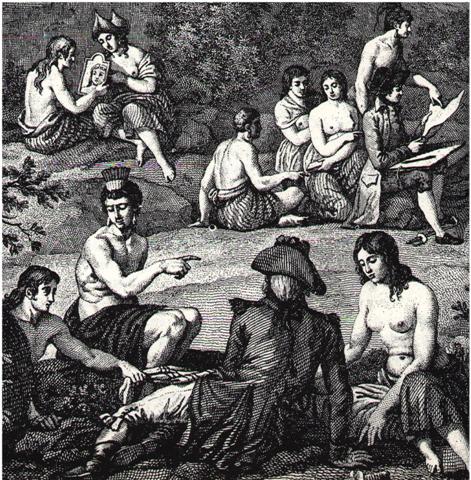

|

(part of a drawing from Easter

Island where thieves are in full action)

|

"If I am allowed to

lift a page from The Golden Bough: each year the

sylvan landscape of old New Zealand provided 'the scene

of a strange and recurring tragedy.' In a small

sweet-potato garden set apart for the god, a Maori

priest enacted a sacred marriage that would be worthy of

his legendary colleague of the grove of Nemi.

Accompanying his movements with a chant that included

the phrase, 'Be pregnant, be pregnant', the priest

planted the first hillocks (puke, also 'mons

veneris') of the year's crop. The priest plays the part

of the god Rongo (-marae-roa, Ha., Lono),

he who originally brought the sweet potato in his penis

from the spiritual homeland, to impregnate his wife (Pani,

the field).

During the period of

growth, no stranger will be suffered to disturb the

garden. But at the harvest, Rongo's

possession is contested by another god, Tuu (-matauenga)

- ancestor of man 'as tapu warrior' - in a battle

sometimes memorialized as the origin of war itself.

Using an unworked

branch of the mapou tree - should we not thus

say, a bough broken from a sacred tree? - a second

priest, representing Tuu, removes, binds up, and

then reburies the first sweet-potato tubers. He so kills

Rongo, the god, parent and body of the sweet

potato, or else puts him to sleep, so that man may

harvest the crop to his own use. Colenso's brilliant

Maori informant goes on to the essentials of the charter

myth:

Rongo-marae-roa

[Rongo as the sweet potato] with his people were

slain by Tu-matauenga [Tuu as warrior]...

Tu-matauenga

also baked in an oven and ate his elder brother

Rongo-marae-roa so that he was wholly devoured as

food.

Now the plain

interpretation, or meaning of these names in common

words, is, that Rongo-marae-roa is the kumara

[sweet potato], and that Tu-matauenga is man."

"...the Hawaiian

staple, taro, is the older brother of mankind, as

indeed all useful plants and animals are immanent forms

of the divine ancestors - so many kino lau or

'myriad bodies' of the gods. Moreover, to make root

crops accessible to man by cooking is precisely to

destroy what is divine in them: their autonomous power,

in the raw state, to reproduce."

"...the aggressive

transformation of divine life into human substance

describes the mode of production as well as consumption

- even as the term for 'work' (Ha., hana) does

service for 'ritual'. Fishing, cultivating, constructing

a canoe, or, for that matter, fathering a child are so

many ways that men actively appropriate 'a life from the

god'."

"Man, then, lives by a

kind of periodic deicide. Or, the god is separated from

the objects of human existence by acts of piety that in

social life would be tantamount to theft and violence -

not to speak of cannibalism.

'Be thou undermost, /

While I am uppermost', goes a Maori incantation to the

god accompanying the offering of cooked food; for as

cooked food destroys tabu, the propitiation is at the

same time a kind of pollution - i.e., of the god.

The aggressive

relation to divine beings helps explain why contact with

the sacred is extremely dangerous to those who are not

themselves in a tabu state. Precisely, then, these

Polynesians prefer to wrest their existence from the god

under the sign and protection of a divine adversary.

They put on Tuu (Kuu), god of warriors.

Thus did men learn how to oppose the divine in its

productive and peaceful aspect of Rongo (Lono).

In their ultimate relations to the universe, including

the relations of production and reproduction, men are

warriors."

"...the Hawaiians had

a sweet-potato ritual of the same general structure as

the Maori cycle. It was used in the 'fields of

Kamapua'a', name of the pig-god said by some to be a

form of Lono, whose rooting in the earth is a

well-known symbol of virile action. While the crops were

growing, the garden was tabu, so that the pig could do

his inseminating work. No one was allowed to throw

stones into the garden, thrust a stick into it, or walk

upon it - curious prohibitions, except that they amount

to protection against human attack. If the garden thus

belonged to Lono, at the harvest the first god

invoked was Kuu-kuila, 'Ku-the-striver'."

(Islands of History) |

|

|