|

TRANSLATIONS

|

Let us begin with

ehu:

| Ehu (cfr kehu)

Ehu ûa, drizzle. Vanaga.

Firebrand. Ehuehu: 1. Ashes. P

Mgv.: ehu, ashes, dust; rehu, a cinder,

ashes. Mq.: ehuahi, ashes. Ta.: rehu,

ashes, soot, any powder. 2. Brown, brownish. P Ta.:

ehuehu, red, reddish. Ha.: kehu, red or sandy

haired. Mq.: kehu, fair, blond. Mgv.:

keukeu-kura, id. Ma.: kehu, reddish brown.

Sa.: 'efu, id. To.: kefu, yellowish. Fu.:

kefu, blond, red. Niuē:

kefu, a

disrespectful term of address. Ragi ehuehu,

a cloudflecked sky. 3. Imperceptible. Churchill.

Pau.:

kehu,

flaxen-haired, blond. Ta.: ehu,

reddish. Mq.: kehu,

blond. Sa.: 'efu,

reddish, brown. Mq.: kehukehu,

twilight. Ha.: ehuehu,

darkness arising from dust, fog, or vapor. Churchill. |

| Kehu (cfr ehu)

Hidden; what cannot be seen because it is

covered; he-kehu te raá, said of the sun when it

has sunk below the horizon. Vanaga.

Kehu, hakakehu, to hide,

disguise, feint, feign, to lie in wait. Kekehu,

shoulder G. Churchill. |

There is a kind of logic

here. When the great fire has ended there are only ashes left. It is

as if the fire had been covered by a carpet of dust - he-kehu te

raá. Hawaiian ehuehu means darkness arising from dust,

fog, or vapour.

Sun is no longer a force to be respected - kefu they could

have said on Niuē.

In a separate page

from the item ehu in my Polynesian dictionary is enumerated the

possible uses of ehu (and the variants in other dialects):

| |

dust |

ashes |

vapor |

darkness |

twilight |

muddy |

| Samoa |

efu |

lefu |

|

nefu |

|

nefu |

| Tonga |

efu |

efu |

|

nefu |

nefu |

ehu |

| Niuē |

efu |

efu |

lefu |

|

|

|

| Uvea |

efu,

nefu |

efu,

lefu |

nefu |

nefu |

|

nefu |

|

Futuna |

efu |

lefu |

|

nefu |

|

|

|

Nukuoro |

rehu |

lefu |

|

|

|

|

| Maori |

nehu |

rehu |

ehu,

nehu, rehu |

rehu,

nehu |

|

ehu |

|

Moriori |

|

rehu |

|

|

|

|

|

Tahiti |

rehu |

rehu |

|

|

rehu |

ehu |

|

Marquesas |

ehu |

ehu |

|

|

ehu |

|

|

Rarotonga |

|

reu |

|

reu |

|

|

|

Mangareva |

ehu,

neu |

ehu,

rehu |

|

|

|

|

|

Hawaii |

ehu |

lehu |

ehu |

ehu,

lehu |

|

|

All 13 dialects have the basic meaning 'ashes', which is a

concept close to 'dust' (which 11 dialects also have). Only the

Moriori fishermen kept straight on the line.

Next we must notice how nehu / nefu appears to be used for ideas

close to but not on the line.

The 'ashes' column has rehu / reu / lehu / lefu in

addition to ehu / efu. It probably means that the basic

form is rehu, not ehu.

The important star Rehua (Antares in Scorpio) announces

the beginning of summer south of the equator:

... The Maori said Rehua (Antares, Ana-mua, the

'entrance pillar' of Tahiti) 'cooks' (ripens) all fruit, because

it inaugurated summer when it rose in the morning sky ...

Rehua is not rehu, but certainly we should assume

a wordplay involving 'ashes'. North of the equator Scorpio could

signify 'ashes', but south of the equator it can hardly do so.

Next we should involve also he-rehua (of Metoro):

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Aa1-5 |

Aa1-6 |

Aa1-7 |

Aa1-8 |

Aa1-9 |

Aa1-10 |

| ko te moa |

e noho ana ki

te moa |

e moa te erueru |

e moa te

kapakapa |

e moa te herehua |

ka hora ka

tetea |

|

e moa te erueru |

Oh

rooster, who scratches diligently! |

|

e moa te kapakapa |

Oh

rooster, who beats his wings! |

|

e moa te herehua |

Oh

rooster, who ties up the fruit! |

|

ka

hora |

Spread out! |

|

ka

tetea |

Have many descendants! |

... Herehua can be translated as

'ties up the fruit' (Barthel 2). The

'fruit' is presumably the 'skull' of the

Sun King, and we should remember the

fate of this skull (cfr at hua poporo

and at ua), not to mention

how the skull of One Hunaphu

fascinated Blood Moon:

... And then the bone spoke; it was

there in the fork of the tree: Why do

you want a mere bone, a round thing in

the branches of a tree? said the head of

One Hunaphu when it spoke to the

maiden. You don't want it, she was told.

I do want it, said the maiden. Very

well. Stretch out your right hand here,

so I can see it, said the bone. Yes,

said the maiden. She stretched out her

right hand, up there in front of the

bone. And then the bone spit out its

saliva, which landed squarely in the

hand of the maiden ...

|

He Rehua could be Antares. Possibly this star indicates

also the end of summer, when he disappears from view in autumn:

"The generally

accepted version of the Rehua myth, according to Best, is

that Rehua had two wives, the stars on either side of

Antares. One was Ruhi-te-rangi or Pekehawani, the

personification of summer languor (ruhi), the other

Whaka-onge-kai, She-who-makes-food-scarce before the new

crops can be harvested." (Makemson)

Poike as 'the time of change of wife' fits with the

changed orientation of the head in Aa1-10, and the mention of

hora (summer) and tetea (growth) would seem to

indicate a change from winter to summer.

And then we should also notice how teatea is part of the

name of item 25, i.e. following ehu in 24 in a way

similar to how tetea follows herehua:

|

24 ko

ehu

ko mahatua a piki rangi a hakakihikihi mahina |

|

e moa

te herehua |

|

Aa1-9 |

|

25 ko

maunga

teatea

a pua katiki. |

|

ka hora

ka

tetea |

|

Aa1-10 |

|

|

Next basic

(polysyllabic words are open to wordplay) key word is piki:

|

Piki

To climb, to mount, to go up; piki

aruga, to surpass; pikipiki, to embark, to go

aboard; hakapiki, to climb. P Pau.: piki,

to climb, to ascend, to mount. Mgv.: piki, to

mount, to go up, to climb. Mq.: piki, pií,

to mount, to climb, to go aloft. Ta.: pii, to

mount. Pikiga, ascent, steps, stairs; Mgv.:

pikiga, a stair, ladder, step. Pikipiki:

rauoho pikipiki, black hair and curly. P

Pau.: tupikipiki, to curl, to frizzle. Churchill.

Pau.: pikiafare, cat. Ta.:

piiafare, id. Churchill. |

Going up (piki)

is necessary when moving eastwards from Mahatua onto the

Poike peninsula and to Maunga Teatea (item 25).

This explanation

is far too simple, though. We must first contemplate what Fornander has to

say:

"PI'I,

v. Haw., to strike upon or

extend, as the shadow on the ground or

on a wall; to ascend, go up.

N. Zeal.,

piki, to ascend. Sam.: pi'i,

to cling to, to climb. Marqu., piki,

to climb, ascend; piki-a, steps,

acclivity. Tong., piki, to adhere

to, to climb, ascend. Fiji.,

bici-bici, a peculiar kind of

marking on native cloth.

Sanskr.,

pin'j, to dye or colour;

pin'jara, yellow, tawny. Lat.,

pingo, to paint, represent,

embroider.

The

marking out or tracing a shadow on the

ground or on a wall was probably the

primary attempt at painting. In the

Hawaiian alone the sense of an ascent,

compared to the lengthening of the

shadows, has been retained. As the sun

descended the shadows were thought to

ascend or creep up the mountain-side.

The sense

of 'marking, tracing', seems only to

have been retained in the Fijian, where

so much other archaic Polynesian lore

has been retained, and thus brings this

word in connection with the Sanskrit and

Latin."

|

It is remarkable

to find ehu (ashes) as an association connected with a

location in the eastern corner of the island - the sun goes down

in the west. But if we are interested in how the shadows are lengthening in late

afternoon we should look east and not west. The shadows in the east

are going up when sun is going down in the west.

These shadows could

possibly be seen creeping upwards on the slope of Poike, but

I do not think such a literal translation is the right one. Instead,

the 'shadows' could refer to how the sky in the east is growing

darker while the rest of the sky dome still is light. The dark

'wall' (or 'cloth') rising in the eastern sky in the evenings certainly was

observed fact. I guess this is what piki rangi indicates.

|

|

With piki rangi

evidently indicating the vertical dimension - Sun going down in the

west and darkness rising in the eastern sky - kihikihi mahina

should by contrast indicate the horizontal dimension:

| Kihi

Kihikihi, lichen; also: grey,

greenish grey, ashen. Vanaga.

Kihikihi, lichen T, stone T.

Churchill.

The

Hawaiian day was divided in three general parts, like

that of the early Greeks and Latins, - morning, noon,

and afternoon - Kakahi-aka, breaking the shadows,

scil. of night; Awakea, for Ao-akea,

the plain full day; and Auina-la, the decline of

the day.

The lapse of

the night, however, was noted by five stations, if I may

say so, and four intervals of time, viz.: (1.) Kihi,

at 6 P.M., or about sunset; (2.) Pili, between

sunset and midnight; (3) Kau, indicating

midnight; (4.) Pilipuka, between midnight and

surise, or about 3 A.M.; (5.) Kihipuka,

corresponding to sunrise, or about 6 A.M. ...

(Fornander) |

Lichen

lies flat on the ground. And also, kihikihi refers to ashes -

by way of the colour grey. When Sun goes down the colours disappear,

excepting those in the scale from black to white, with grey in the

center. Moon (Mahina) cannot produce any other colour than

white or gray.

Once again

Fornander delivers the necessary link between words and the cosmic

structure: The

time of sunset was Kihi according to the Hawaiians, and we

can infer it means 'the time when everything becomes grey'.

Though Moon is coloured yellow from Sun, and the stars

have all the colours. Kihikihi refers to the surface of the

earth, not to the 'inhabitants of the sky'.

|

|

We are now ready

to look again at the whole name:

24

ko ehu ko mahatua a piki rangi a hakakihikihi mahina

First comes ehu,

presumably in order to indicate how the great fire in the sky no

longer is 'alive'.

Next comes a

'reflection', in form of the contrast with twin events in the east: rising darkness in the

sky (piko rangi) together with the colour grey (kihikihi

) covering earth below. This grey colour comes from Moon (Mahina),

she makes gray (hakakihikihi).

This contrast

between the sun event in the west and the night events in the east is - it seems - a characteristic of the place

Mahatua. The name could refer to mahatu, to fold:

| Hatu

1. Clod of earth; cultivated land; arable

land (oone hatu). 2. Compact mass of other

substances: hatu matá, piece of obsidian. 3.

Figuratively: manava hatu, said of persons who,

in adversity, stay composed and in control of their

behaviour and feelings. 4. To advise, to command. He

hatu i te vanaga rivariva ki te kio o poki ki ruga ki te

opata, they gave the refugees the good advice not to

climb the precipice; he hatu i te vanaga rakerake,

to give bad advice. 5. To collude, to unite for a

purpose, to concur. Mo hatu o te tia o te nua, to

agree on the price of a nua cape. 6. Result,

favourable outcome of an enterprise. He ká i te umu

mo te hatu o te aga, to light the earth oven for the

successful outcome of an enterprise. Vanaga.

1. Haatu, hahatu,

mahatu. To fold, to double, to plait, to braid;

noho hatu, to sit crosslegged; hoe hatu,

clasp knife; hatuhatu, to deform. 2.. To

recommend. Churchill.

In the Polynesian dialects proper, we

find Patu and Patu-patu, 'stone', in New

Zealand; Fatu in Tahiti and Marquesas signifying

'Lord', 'Master', also 'Stone'; Haku in the

Hawaiian means 'Lord', 'Master', while with the

intensitive prefix Po it becomes Pohaku,

'a stone'. Fornander. |

If grey

covers the earth due to the light from Moon, she can be anywhere in

the sky. It is not necessary to have her low on the horizon in the

west (as a contrast to Sun low on the horizon in west). But if she is there, then it should be

a full

moon and a low tide. A low tide is in harmony with earth high above

the level of the sea. Which agrees with the situation on Poike.

Earth is also the meaning of hatu.

But in Barthel 2

he has coordinated the 24th Ehu item with the beginning of the

lunar cycle:

|

30-32 |

19 Hia

Uka |

20 Hanga

Ohiro |

|

1-3 |

21 Roto

Kahi |

22 Papa

Kahi |

|

2-4 |

23 Puna

Atuki |

24 Ehu |

|

3-5 |

25 |

26 |

|

4-6 |

27

Hakarava |

28 Hanga

Nui |

|

5-7 |

29

Tongariki |

30 Rano

Raraku |

I will not attempt

to revise his coordinations between lunar nights and

the items on the 2nd list of place names. But I guess he went

wrong at Hanga Ohiro:

"Hanga

Ohiro is located (north)west of Anakena, in the exact

spot where the crescent of the new moon could be seen from the royal

residence above the shore in the western sky. At this point, the

place name and the phase of the moon coincide, and the beginning of

the month is linked to the royal residence in much the same way as

the beginning of the year on the 'first list of place names'. Thus,

when the traditions tell that those versed in Rongorongo used

to come to Anakena in the first quarter of the moon (RM:246),

the accounts refer to the lunar time appropriate for such meetings,

and the statement makes sense in terms of our lunar model."

If we move

Hanga Ohiro from the last day of the lunar month to night number

20, the arguments for Anakena as a place to look for the new

moon will not be changed. Ohiro (1) is the opposite of

Hanga Ohiro (20).

|

|

There is more to

say of course, there always is. In order to keep track of time over the year it

could be debated whether to look at the sky in the early morning to find

out which constellation or star is rising heliacally, or whether

to look in the evening to find out which constellation or star

the sun goes down with.

Neither

alternative is very good, because you must do such observations at a

certain time and you must not look straight in the face of Sun.

Maka wela the Hawaiians said, your eyes will be burnt:

... Like the sun,

chiefs of the highest tabus - those who are called 'gods', 'fire',

'heat', and 'raging blazes' - cannot be gazed directly upon without

injury. The lowly commoner prostrates before them face to the

ground, the position assumed by victims on the platforms of human

sacrifice. Such a one is called makawela, 'burnt eyes' ...

You could avoid

looking Sun in the eye by observing which star was rising before Sun

(or descended after Sun in the evening). However, there is another

complication:

...

Colonists who arrived in New Zealand from Central Polynesia during

the Middle Ages and intermarried with the tangata whenua,

'people of the land', found themselves between the horns of a

calendrical dilemma. They must either convert the aborigines to the

Pleiades year beginning in November-December or themselves adopt the

Rigel year [together with heliacal rising observations] and bring

down the wrath of their ancestors on their own heads

...

A star will rise

in the early morning at different times depending on the latitude of

the observer. Makemson thought the Rigel year was a consequence of

some island 10º south of the equator:

... can be explained only on the assumption that the very first

settlers ... brought the Rigel year with them ... some other land

10° south of the equator where Rigel acquired at the same time its

synonymity with the zenith ..

I am not

convinced. The Gilbertese sky dome said Rigel was located at 8º S,

Antares at 26º S, and the Pleiades at 24º N, numbers filled to the

brim with other 'sacred' meanings:

Once (in pyramid

times) Sun reached to 24º on either side of the equator. 8 is the

'perfect number', and 26 is twice 13 (and also where Easter Island

is located). The Gilbertese had all 3 numbers correct, including

Rigel at 8º S. They were careful with the details. Moving across

the vast ocean with an orientation 2º wrong would spell 'disaster'.

However, when

observing a star rising it was necessary to know the latitude of the

observer, to compensate for the curvature of the earth. To relate

the position of a star which is rising (or going down) to the local

horizon is possible, but not a very good method. Not for a people

making voyages up and down the latitudes.

But there is an

ingenous method to determine the time of the year independent of

latitude or other local phenomena (such as mountains hiding the

horizon), viz. to use the moon. When there

is a full moon we know there is a straight line between moon and sun

and with us somewhere in the middle. A full moon can be seen from all

latitudes, the moon is so distant that the latitude of the observer

is insignificant.

If the observer

knows his starry sky well, he will immediately be able to determine

which location the full moon occupies, i.e. which stars are close. Then

by a quick mental operation he will twirl the starry globe in his

head to find the 'antipodal' point in which sun must be, which

'station' on the path of the year sun is in, what the time of the

year is. This method gives the same result irrespective of latitude.

The method is described by Worthen.

I remembered this

when reflecting on why piki appears in item 24.

Watching the shadows created by the rays of Sun is similar to

watching the full face of Moon. There is a straight line connecting

a shadow with its source, likewise the illuminated face and its

source.

The double calendar system of India could have been used

also in the rongorongo texts. The appearance of the 3 bird

islets outside Rano Kau (at the beginning of spring) appears

to be reflected in the 3 'peaks' of Maunga Teatea (not far

from Rano Raraku):

Kau means

midnight according to Fornander. At the other end we find

noon (Ao-akea). Akea can be transcribed as atea,

presumably the central 'daytime' of Sun. The double form (teatea)

means 'heavy rain' according to the Mangarevans, which indeed agrees

with what we have understood comes at the 'back side' (side 2 of a

'tablet'). Ehu ûa (not far from Rehua) means

drizzle.

Maybe Maunga

Teatea should be crossed from right to left. The last of the

'front side' would then be item 24 (Mahatua). In the G text

day 240 is at Gb1-10 and 1-10 is the same number as in Aa1-10:

|

|

"In Hindu legend there

was a mother goddess called Aditi, who had seven offspring.

She is called 'Mother of the Gods'.

Aditi,

whose name means 'free, unbounded, infinity' was assigned in the

ancient lists of constellations as the regent of the asterism

Punarvasu. Punarvasu is dual in form and means 'The

Doublegood Pair' ['Two Good Again' according to Allen]. The singular

form of this noun is used to refer to the star Pollux. It is not

difficult to surmise that the other member of the Doublegood Pair

was Castor.

Then the constellation

Punarvasu is quite equivalent to our Gemini, the Twins. In

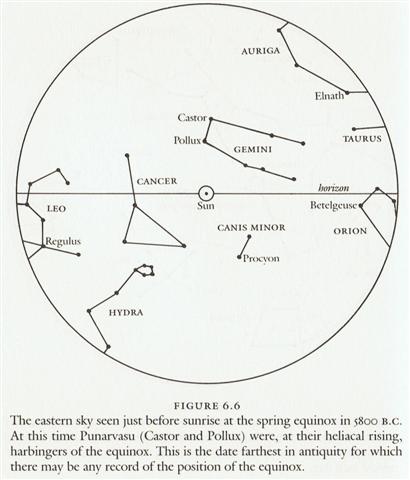

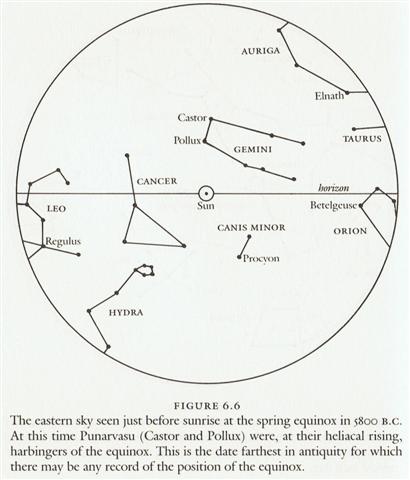

far antiquity (5800 B.C.) the spring equinoctial point was predicted

by the heliacal rising of the Twins (see fig. 6.6). By 4700 B.C. the

equinox lay squarely in Gemini (fig. 6.7).

Punarvasu

is one of the twenty-seven (or twenty-eight) zodiacal constellations

in the Indian system of Nakshatras. In each of the

Nakshatras there is a 'yoga', a key star that marks a

station taken by the moon in its monthly (twenty-seven- or

twenty-eight-day course) through the stars. (The sidereal period of

the moon, twenty-seven days and a fraction [27.3] , should be

distinguished from the synodic, or phase-shift period of 29.5 days,

which is the ultimate antecedent of our month.)

In ancient times the

priest-astronomers (Brahmans) determined the recurrence of the

solstices and equinoxes by the use of the gnomon. Later they

developed the Nakshatra system of star reference to determine

the recurrence of the seasons, much as the Greeks used the heliacal

rising of some star for the same purpose.

An example of the operation of the Nakshatra system in

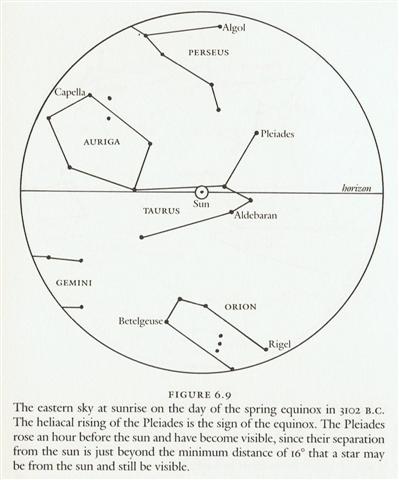

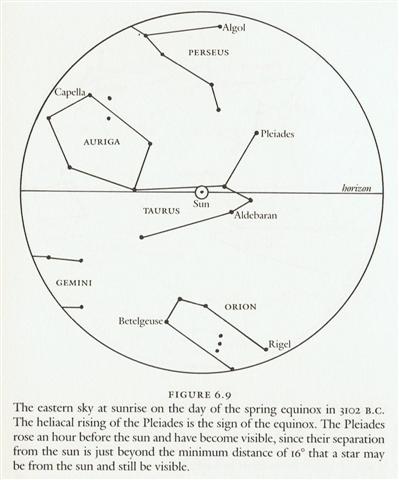

antiquity can be seen in figure 6.9

Here we see that the

spring equinox occurred when the sun was at its closest approach to

the star Aldebaran (called Rohini by the Hindus) in our

constellation Taurus. But, of course, the phenomenon would not have

been visible because the star is too close to the sun for

observation.

The astronomers

would have known, however, that the equinoctial point was at

Aldebaran by observing the full moon falling near the expected date

or near a point in the sky exactly opposite Aldebaran (since the

full moon is 180º from the sun), that is, near the star Antares; see

fig. 6.15.

The system of

Nakshatras, then, is quite distinct from systems that use the

appearance of heliacally rising or setting stars as the equinoctial

marker. Furthermore, the Indian system is all but unique in that two

calendar systems competed with each other - a civil system, in which

the year's beginning was at the winter solstice, and a sacrificial

year, which begins at the spring equinox. The beginning of the

former was determined by the Nakshatra method, observing the

winter full moon's apparition near the point of the summer solstice

in the sky (as explained above).

The arrival of the

beginning of the sacrificial year might be determined by the

Nakshatra method - observation of the spring full moon near to

the autumn Nakshatra in Virgo. More commonly, however, it was

determined as in the Greek system, by direct observation of the

heliacal rising of a sign star.

In the current

calendar, for example - one unchanged since the fifth century A.D. -

the yoga star of the Nakshatra Ashvini (beta

Arietis) ushers in the spring equinox at its heliacal rising."

(Worthen) |

|