|

TRANSLATIONS

The first pages of hupee:

|

A few preliminary

remarks and imaginations:

1.

I guess the basic meaning of 'mucus' could be the

slimy mixture of land

and sea squeezing up between your toes when treading on

the muddy beach at low tide.

This idea points to the cosmic border line between 'land' and 'sea',

i.e. the nourishing place after the vai season has passed

away - spring. The 'birth of new land' comes with 'high tide going

away', when 'the primal embrace' is torn apart:

...

Rangi and

Papa existed in close and loving embrace until a spirit without

origin forced them asunder. His name was Rangi-tokona,

Sky-propper, and he corresponds with the Tui-tee-langi of

Samoan myth. Rangi-tokona first politely requested Rangi

and Papa to separate but they refused. Then he lifted

Rangi higher and higher by means of magical incantations and

propped him up on ten pillars which he placed one on top of the

other so that they formed a single, long support. Then for the first

time light shone in upon the earth ...

A wordplay between hopu and hupe(e) is

possible, and in Marquesan hopu means 'to embrace':

| Hopu

1. To wash oneself, to

bathe, 2. Aid,

helper, in the following expressions: hopu kupega, those who help

the motuha o te hopu kupega in handling the

fishing nets; hopu manu, those who served the

tagata manu and, upon finding the first manutara

egg, took it to Orongo. Vanaga.

Bath; to bathe, to cleanse (hoopu).

Pau.: hopu, bath; to bathe. Ta.: hopu, to

dive. Churchill.

Mq.: hopu, to embrace, to clasp

about the body. Ma.: hopu, to catch, to seize.

Churchill. |

|

|

2.

The cycle of ebb and high tide is

governed by Moon, and twice in a day her water is flowing

in and out, as if breathing. When she is straight above or straight

down it is the time of flood, her water follows her. This means the

times when water recedes are connected with Moon at the horizon in

the west or at the horizon in the east.

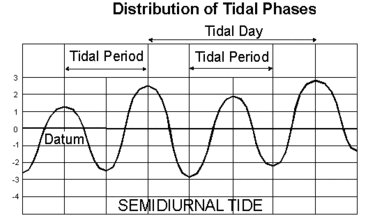

Picture from Wikipedia where it is stated that Moon

returns to the same place in the sky after about 24 hours and 50

minutes, which means the tidal period will be half as long (12 hours

and 25 minutes):

| ... Most coastal areas experience two

high and two low tides per day. The gravitational effect

of the Moon on the surface of the Earth is the same when

it is directly overhead as when it is directly

underfoot. The Moon orbits the Earth in the same

direction the Earth rotates on its axis, so it takes

slightly more than a day—about 24 hours and 50

minutes—for the Moon to return to the same location in

the sky. During this time, it has passed overhead once

and underfoot once, so in many places the period of

strongest tidal forcing is 12 hours and 25 minutes. The

high tides do not necessarily occur when the Moon is

overhead or underfoot, but the period of the forcing

still determines the time between high tides.

The Sun also exerts on the Earth a

gravitational attraction which results in a (less

powerful) secondary tidal effect. When the Earth, Moon

and Sun are approximately aligned, these two tidal

effects reinforce one another, resulting in higher highs

and lower lows. This alignment occurs approximately

twice a month (at the full moon and new moon). These

recurring extreme tides are termed spring tides. Tides

with the smallest range are termed neap tides (occurring

around the first and last quarter moons) ... |

Yesterday evening I happened to learn from the Life

series on TV that in the extreme south of Africa there are baboons

who are living in a tough environment with scarce food resources.

They had learned that at the time of spring flood (about every

fortnight) it was possible, when the sea was drawing back, to go out

among the kelp otherwise inaccessible in order to search for sharks'

eggs, a very nutricient food.

I remembered from ika hiku: ... Mermaid's

purses (also known as Devil's Purses) are the egg cases of skates,

sharks and rays. They are among the common objects which are washed

up by the sea. Because they are lightweight, they are often found at

the furthest point of the high tide. The eggcases that wash up on

beaches are usually empty, the young fish having already hatched out

...

The 'living purses' are far out, but the empty ones

are high up on the beach. This makes the image of a shark's

egg useful as a symbol which easily can be changed from living (with

'legs') to dead (without 'legs'). We should keep this possibility in

mind when trying to understand such glyphs as for instance:

The

peculiar idea of chiefs being 'sharks who walk on land' fits

with finding empty cases high up on the beach, the inhabitants

evidently having moved inlands.

|

|

3.

With Moon governing not only the tides but also time in general, it

is not strange to count time in doublemonths. Waxing and waning

should occur twice also in the 'her longer day', the month (her

ordinary day being 24 hours and 50 minutes).

Such must be inferred from the theory of correspondences.

Maybe, therefore, hupee can occur in 2 different locations

in a calendar for the year - or in any type of calendar for that

matter. A diurnal pattern is in harmony with the for us now

civilized people foreign view of 2 'years' in a

year, a 'summer year' and a 'winter year'. But each year evidently

has one

'ebb' period and one period of 'high tide' (or in agricultural terms

one season 'in leaf' and one 'in straw'). A semidiurnal pattern

would be more appropriate for people living by the sea and Moon is needed

whenever time is to be counted.

At the number of the beast, on the front side of the

Tahua tablet, the 'deluge' will from our new perspective not

necessarily be a description of an 'inundation' in the sky (the region

of 'earth' sinking down into 'water' due to the undulation of the

sky dome), nor a reflection of old

stories about how the Nile - or some other great river - regularly

is flowing over its banks, nor of memories of monsoon rains in some

ancient homeland (cfr at maitaki):

|

|

|

|

|

|

Aa6-64 |

Aa6-65 |

Aa6-66 |

Aa6-67 |

Aa6-68 |

Quite possibly the origin lies much earlier, when man

like the baboons of South Africa learned the value of keeping in

touch with time in order to find food on the exposed tidal flats.

The connection between tides and Moon was in Polynesia evidently encoded by her

'face' (a reflection of where the sun is) and when / where Moon is to

be seen in the sky. Sun and earth are the determining factors. Together they define the moon. But seen from the other

direction Moon rules over Sun and also what happens down on Earth,

which of course is a more practical and commonsense view.

An example is offered by the Hawaiian Moon calendar (cfr at

marama) where the tides are of

central importance, for instance:

... On the evening

of Hilo there is a low tide

until morning. On this night the women fished by

hand (in the pools left by the receding sea) and the men

went torch fishing. It was a calm night, no tide until

morning. It was a warm night without puffs of wind; on

the river-banks people caught goby fish by hand and

shrimps in hand-nets in the warm water. Thus passed the

famous night of Hilo. During the day, the sea

rose washing up on the sand, and returned to its old

bed, and the water was rough ...

We should here notice, though,

that in the night of Hilo the water was warm, which does not agree with how Bishop

Jaussen explained hupee, viz. as 'rhume, air froide'.

Also 'mucus from the nose' and 'night-dew' give associations to a

chilly environment.

|

|

A short summary:

|

1 |

Hilo |

On the evening

of Hilo there is a low tide

until morning. On this night the women fished by

hand (in the pools left by the receding sea) and the men

went torch fishing. It was a calm night, no tide until

morning. It was a warm night without puffs of wind; on

the river-banks people caught goby fish by hand and

shrimps in hand-nets in the warm water. Thus passed the

famous night of Hilo. During the day, the sea

rose washing up on the sand, and returned to its old

bed, and the water was rough. |

|

2 |

Hoaka |

On the evening

when Hoaka rises there is

low tide until morning, just

like the night of Hilo. |

|

3 |

Ku-kahi |

|

|

4 |

Ku-lua |

On that evening

the wind blows, the sea is choppy, there is low tide but

the sea is rough. The next morning the wind blows gently

and steadily. It was a day

of low tide. The sea receeded

and many came down to fish. |

|

5 |

Ku-kolu |

A day of low

tide; but the wind blows until

the ole night of the Moon. Many fishermen go out

during these days after different sorts of fish. The sea

is filled with fleets of canoes and the beach with

people fishing with poles and with women diving for

sea-urchins, the large and small varieties, gathering

limu, spreading poison, crab fishing, squid

spearing, and other activities.During the wet season

these are stormy days rather than clear; it is

only during the dry season when these low tides prevail,

that fish are abundant, the sea-urchins

fat and so forth ... |

|

6 |

Ku-pau |

It is

a day of low tide like the others

until the afternoon, then the sea rises, then ebbs,

until the afternoon of the next day.

The wind blows gently but it is scarcely perceptible.

The sand is exposed. |

|

7 |

Ole-ku-kahi |

It is a day of

rough sea which washes up the sand and lays bare the

stones at the bottom. Seaweed of the flat green variety

it torn up and cast on the shore in great quantity. |

|

8 |

Ole-ku-lua |

...the second

[night] of rough seas. It is a good night for torch

fishing, for the sea ebbs a

little during the night. |

|

9 |

Ole-ku-kolu |

The sea is rough

as on the first two days of this group. The

tide is low

and there is torch fishing at night

when the sea is calm. Some nights it is likely to

be rough. |

|

10 |

Ole-pau |

|

|

11 |

Huna |

|

|

12 |

Mohalu |

There is a

low tide

and the night is the sixth of the

group. |

|

13 |

Hua |

The

tide is low

on that day and it is the seventh of the group. Such is

the nature of this night. |

|

14 |

Akua |

This is the

eighth of this group of nights. It is a day of

low or high tide,

hence the saying: It may be rough, it may be calm. |

|

15 |

Hoku |

|

|

16 |

Mahea-lani |

It is a day of

low tide. |

|

17 |

Kulu |

This is the

eleventh of the nights of this group and on this night

the sea gathers up and replaces the sand. |

|

18 |

Laau-ku-kahi |

There is sea,

indeed, but it is only moderately high. |

|

19 |

Laau-ku-lua |

The sea is rough. |

|

20 |

Laau-pau |

A day of

boisterous seas. |

|

21 |

Ole-ku-kahi |

A day of rough

seas so that it is said: 'Nothing (ole) is to be

had from the sea.' |

|

22 |

Ole-ku-lua |

...a day of

rough seas. |

|

23 |

Ole-pau |

|

|

24 |

Kaloa-ku-kahi |

The weather is

bad with a high sea. This is the last rough day, the sea

now becomes calm. |

|

25 |

Kaloa-ku-lua |

|

|

26 |

Kane |

It is

a day of very low tide but

joyous for men who fish with lines and for girls who

dive for sea-urchins. |

|

27 |

Lono |

The

tide is low,

the sea calm, the sand is gathered up and returned to

its place; in these days the sea begins to wash back the

sand that the rough sea has scooped up. This is one

account of the night of Lono. |

|

28 |

Mauli |

...a

day of low tide. 'A sea that

gathers up and returns the sand to its place' is the

meaning of this single word. |

|

29 |

Muku |

...a

day of low tide, when the sea

gathers up and returns the sand to its place, a day of

diving for sea-urchins, small and large, for gathering

sea-weed, for line-fishing by children, squid-catching,

uluulu fishing, pulu fishing and so forth.

Such is the activity of this day. |

What seems to have been of main interest were days with a low tide,

for 15

out of 29 nights a low tide is mentioned.

Especially noteworthy is the fact that 'growing Moon' is

characterized by low tide, while for 'waning Moon' - excepting the

last 4 nights - a low tide is not mentioned. When Moon is growing it

corresponds to the time when Sun in spring is moving higher and

higher leaving Mother Earth down below. Sky (Sun) is torn apart from

the loving embrace.

The last 4 nights of waning Moon (from Tane

onwards) could correspond to how 'the front side' of the year is

beginning already at the end of the 'back side' of the year.

In the 17th (or 11th) night (Turu) a new season ('the flood'

or 'the back side')

is coming. After a further 10 nights 'the low tide' returns, in the 26th night

of Tane.

We should furthermore notice that also the 7th night is a night of

change (which probably means 'of Moon'):

'It is a day of

rough sea which washes up the sand and lays bare the

stones at the bottom. Seaweed of the flat green variety

it torn up and cast on the shore in great quantity.'

17 - 11 = 6 and this difference between my ordinal numbers in the

table above and what

is stated in the calendar is verified at Atua, which I have

given number 14 but which according to the calendar should be regarded as number 8.

The Tane night - which is number 26 counted

from the beginning with Hiro as number 1 - will probably be

number 20 in the view of the calendar maker. Once again number 20 is

found to be the limit for counting nights in a month.

And the first night is not Hiro but

Kore-Tu'u-Tahi. When counting to 20 nights in a month you should

not begin until Moon has risen far enough and you should stop before

she has shrunken too much.

The description of events and conditions according to the calendar apparently is mainly a theoretical construct rather than a

reflection of what was truly observed in mother nature during a

month. As such it is of greater interest and value for us than a

structure based on pure observational records.

|

|