|

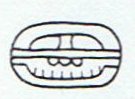

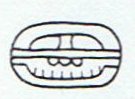

5 Tzec (Zec) |

|

| "...the Aztecs made sacrifices for 'the birth of the mountains' during their equivalent month, Tepeilhuitl ..." |

|

|

I immediately imagine I can see the sky roof coming up in the monument glyph - I can see what I hope to find. 8 short marks like the 'feather' signs in the rongorongo texts could express the sun light at last arriving down on earth. In Gates' Tzec glyph the top has opened up, another sign of sun light being allowed to enter, I imagine. The Aztecs may have thought about the phenomenon as due to the mountains pushing the sky up. |

|

"Two signs, Tzec and Pax, require the flaring open top, to distinguish them respectively from the chuen and the tun normal sign, on which they are formed." (Gates)

"The 11th day-name, in all the calendars, is Monkey: Batz in both Tzeltal and Quiché, Ozomatl in Nahuatl. The word chuen is not Maya; but on the authority of the names Hun-Batz, Hun-Chouen, the two monkey-brothers in the Popol Vuh, and the Tzeltal Chiu (given in the Ara ms. dictionary as a kind of monkey), we must accept Chuen as the original word, with this significance." (Gates)

Monkeys live in trees, and it could be an allusion to the 'Tree' now pushing the sky up. "Pictographs of monkey heads or full figures of monkeys sometimes replace the glyph for kin 'day'. This usage has been explained in terms of the associations of the Sun God with monkeys ..." Maybe the bottom middle sign in chuen is a sign to illustrate the 'sun tree' growing upwards. |

|

"The same glyph [chuen] is found to indicate the period of twenty days, known from Landa as the uinal (i.e., win-al). 'Month', however, appears in the Motul dictionary as uen, and chuen might be a compound chu-uen ..." I draw the conclusion that chu-uen, ought to mean 'sun month' (in distinction from an older moon-month), with chu = the sun. Dividing time into periods ('months') with 20 days indicates - I believe - a connection with the idea of 'fire hands', the seat of rationality and order. To see is to understand, and daylight is needed. Tzec is the 5th chuen, equal to the basic fire number (rima).

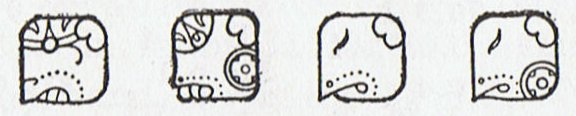

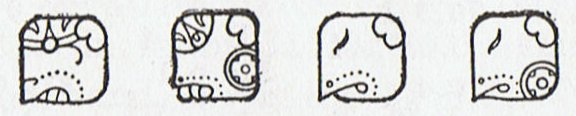

The probability is high that the 'month-glyphs' in rongorongo, designed as what may be a monkey ('kiore') up in a tree (henua), represent 20 days. In other words, this may be the rongorongo 'monkey' glyph type (or uinal):

|

... The month of twenty days, known to the Yucatec Maya and modern students as the uinal, is designated by the same glyph as the day called Chuen in Yucatec and Batz in other Maya languages. The true phonetic rendering is still unknown, or at least has not been established to the satisfaction of most scholars studying the glyphs ...

I should have mentioned in my comments above about chu-uen = sun-month, that the moon was named u, and that therefore uen = month probably stands for u-en (moon-en).

Another reflection is that the eye lashes of Mayan death signs - exemplified here by Cimi (the 6th day) possibly explain the inverted such eye lashes in for instance Tzec:

In the rongorongo system of writing such reversals (meaning 'the opposite of') are common:

|

|

|

|

| Aa1-16 |

Aa1-17 |

Aa1-18 |

Aa1-19 |

Both the Maya and the rongorongo masters saw 'eyelashes' in front (Aa1-19) or up (Tzec) as 'life and light'.

Tzec seems to announce the arrival of the 'monkey' (sun). Chuen is the 11th day name. There are 20 day names and Chuen is in the center. The preceding day is Xul, i.e. the 10 day name is the same as the 6th month name:

|

|

| 11 Xul |

6 Xul |

"No glyphs have given more trouble than these two in the arranging of their classification. The first is of the day Oc, the second the month Xul. The word for dog in Maya is pek; in Quiché, Choltí, Tzeltal, etc. tzi; the word xul in Maya means 'end'." (Gates)

Now back to vina-l and Vinapu. Anakena and Vinapu represent the sky respectively the watery season, I think:

|

1. Hanga Te Pau, the landing site of Ira and his band of explorers, is the natural anchorage for those approaching Vinapu by sea. The remarkable stone fronts of the ahu of Vinapu are all facing the sea. The explorers landed at Hanga Te Pau during the month 'Maro', that is, June ...

2. The cult place of Vinapu is located between the fifth and sixth segment of the dream voyage of Hau Maka. These segments, named 'Te Kioe Uri' (inland from Vinapu) and 'Te Piringa Aniva' (near Hanga Pau Kura) flank Vinapu from both the west and the east. The decoded meaning of the names 'the dark rat' (i.e., the island king as the recipient of gifts) and 'the gathering place of the island population' (for the purpose of presenting the island king with gifts) links them with the month 'Maro', which is June. Thus the last month of the Easter Island year is twice connected with Vinapu. Also, June is the month of summer solstice [a mistake: winter solstice], which again points to the possibility that the Vinapu complex was used for astronomical purposes.

3. On the 'second list of place names', Hanga Te Pau is called 'the middle (zenith) of the land' (he tini o te kainga). This may refer to a line bisecting the island, but it can just as easily mean the gathering of a great number (of islanders). The plaza (130 x 130 meters) would have been very well suited for this purpose.

4. The transformation of the 'second list of place names' into a lunar calendar links Hanga Te Pau and Rano Kau. A similar linkage occurs in connection with the third son of Hotu Matua between the 'pebbles of Hanga Te Pau' and his name 'Tuu Rano Kau'. There can be no doubt that Vinapu was dependent on the economic resources of the large crater.

5. In the 'scheme of lunar nights', Hanga Te Pau introduces the second half of the month in contrast to Hanga Ohiro, which introduces the first half. That means that Vinapu and Anakena were calendary opposites. Based on the encoded information gained from numbers 1 and 2, 'Maro' (for the Vinapu area) is contrasted with 'Anakena' (for the Anakena area) - or, to put it differently, the last month of the year is contrasted with the first month of the year.

6. The fact that the year ends at Vinapu and begins anew at Anakena may have meaning beyond the obvious transition of time and may also indicate a historic transition. The carbon-14 dating test assigned a much earlier date to Vinapu (ninth century) than to Anakena. This raises the question of an 'original population', which, according to the traditions, lived along the northern rim of Rano Kau (i.e., inland from Vinapu) and their relationship to the explorers.

7. During his visit in 1886, Thomson wrote about the plaza:

Immediately behind this platform (that is, Ahu Vinapu) a wall of earth encloses a piece of ground about 225 feet in diameter and circular in shape. This is believed to have been the theater of the native ceremonies, and perhaps the spot where the feasts were held. (PH:512-513)

Two names, he tini o te kainga ('a great number of people from the homeland') from the 'second list of place names' and te hue ('the gathering'), a local name from the area of the third-born, tend to confirm the statement by Thomson, and so does a revealing passage about Vinapu in one of the traditions (ME:373; Knoche 1925:266). This passage deals with a festival (te koro o vinapu), during which a young woman appears, disguised as a bird (poki manu, Campbell 1971:224). She is the daughter of Uho, who had married Mahuna-te-raa ('sun with curly hair? hidden sun?') in the 'land of the nocturnal eye' (henua mata po uri). But she longed for her homeland, the 'land of the light and clear eye' (henua mata maeha) until she was able to return to it.

Uho's journey across the sea began on the beach of Anakena, that is, the 'opposite' place from Vinapu. In the foreign land Uho instructs her daughter how to transform herself into a bird. The tale is interesting because it is the only one with the motif of a solar marriage. As such, it is possibly connected with the solar orientation of the Vinapu complex. Furthermore, the RAP. text lists the contrasting qualities of the two regions as mata pu uri vs. mata maeha.

Transferred to the fourfold division of the island, the contrast of 'night darkness' vs. 'daylight' corresponds to the contrast between the region of the night, including the landing site of Ira, which belongs to the third son, and the region of the noon sun, including the landing site of Hotu Matua, which belongs to the first-born. This tale again emphasizes the contrasting values assigned to Anakena and Vinapu. According to an unpublished fragment by Arturo Teao, which was recorded by Englert in 1936, 'Uho' was born in 'Hare Tupa Tuu', that is, in the house of the first-born.

However, having been born in Anakena, she would not have gone on a journey across the sea upon being married, but would have left her home for a region on the other side of the island. Her husband, 'Mahuna Te Raa', may have been a quasi-historic figure connected with the Vinapu complex. Since mata also refers to the political unit of a tribe on Easter Island, the metaphysical contrast arising from the fourfold division of the land also has its political counterpart in the form of four different tribal attributes:

|

1. mata maeha |

for Tuu Maheke and Anakena |

|

2. mata nui |

for Miru |

|

3. mata po uri |

for Tuu Rano Kau and Hanga Te Pau |

|

4. mata iti |

for Hotu Iti |

The first pair (numbers 1 and 2) expresses positive qualities, the second (numbers 3 and 4) mostly negative ones. This again seems to foreshadow the later conflict between the tribal federations." (Barthel 2) |

With new year the sun baby is born. Water belongs to the 4th quarter, not in the 1st. The inundation is over. The land emerges again from under the waves.

Vinapu, I imagine, is 'sun-20' (wina-l) plus a reference to both Rano Kau and to the circular area for gathering (hue) the 'great number of people from the homeland' (he tini o te kaiga) in the time of Te Piringa Aniva (the last 24th of the year).

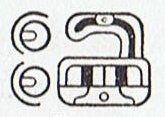

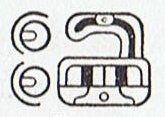

Expressed in Mayan, it is the time of Ahau (the 20th 'day'), when sun is at his lowest:

It is as if the sun (bottom inner circle) is inside a crater (pu). The awakening (in the last day of Uayeb), with the 'eyelashes going up' as in the instantaneous 'bird flight' ('fire') to Anakena, could explain the eyes in front in Uayeb:

... a young woman appears, disguised as a bird (poki manu, Campbell 1971:224). She is the daughter of Uho, who had married Mahuna-te-raa ('sun with curly hair? hidden sun?') in the 'land of the nocturnal eye' (henua mata po uri). But she longed for her homeland, the 'land of the light and clear eye' (henua mata maeha) until she was able to return to it ...

Vinal means not only 20 but also 'man':

"Vinal, as correctly noted by Seler, is not and cannot be derived from the Maya U, moon, by any known derivative word method, either in Maya or any other Mayance tongue.

Further, vinak, vinic, is the universal Mayance word for man; from it comes vinikal, viniquil, in the different languages, meaning 'manhood', and also 'score'.

It is the common word in Quiché for score. The count is vigesimal, the 20 hand and foot digits of the man, represented by the dots, bars and kal, just as by the Roman I, V, X.

To accept a shortening in Maya to the term vinal does violence to no principle, and vinal is the calendric 'score of days'.

The evidence on the identity between the words for 'man' and the 'score of days' is too strong to be ignored. Flores, Cakchiquel Arte, 1753, says 'Para contar Xiquipiles de cacao de veinte en veinte: hu-k'ala, ca-k'ala, etc. Para contar meses al modo de los Indios, que es de veinte en veinte: hu-vinak, ca-vinak, etc. Para contar años de veinte en veinte: hu-may, ca-may, etc.'

In his Pokoman grammar, ms. 1720, Moran tells us definitely that k'al is used for score, 20, ad omnia, para todo, except in the single case of four-score, 80, for which cah-vinak is used.

But to count days in Pokoman one always uses vinak, just as the Quiché-Cakchiquel above. (Pokoman also uses the above Quiché term May for the Maya Katun; and, incidentally, Quiché and Pokonchi give us k'al, ok'ob, chuy, calab for the numerals from 20 to 160,000; the terms for the two higher periods habe been lost.) The southern branches thus use the word vinak, man, in exactly the sense and place of the Yucatan vinal." (Gates)

The meaning of the tagata glyph type - denoting a fully grown season, as I have deduced - here gets confirmation. Maybe also a numerical value (not necessarily 20) can be assigned to tagata?

All the people (from the homeland) gather at Vinapu, it seems, because it is time for 'vinal'. All hands and all feet congregate. Hands and feet are empty.

The Pokoman used cah-vinak for 4 times 20, therby expressing a qualitative difference associated with a multiple of 4. Otherwise they said k'al instead. Maybe Vinapu likewise is a special '4 times' (a multiple of 20)?

There is more. There were two terms for 20 among the Maya: vinal and kal (k'al among the Pokoman). Therefore there ought to have been also two glyph types, I think. But that seems not to have been the case:

|

|

| kal, vinal |

Ahau |

"Landa in telling us that, besides the 20-day time count, they had another month, called U, moon, does no more than recognize the natural phenomenon, as done by every non-city dweller, whatever the keepers of books may work with.

We are told that the word vinal was 'derived' from U, because the moon is notable or 'alive for twenty days of her term', something that is first not true, and wherein the necessity for such an explanation defeats its aim.

We have not a trace anywhere of the calendric use of a 30-day, or moon-month, at any time. And further, the numeral 20 is too deeply rooted in all Maya mathematics and time-counting, to have come up on any such way ...

To say nothing of the overlooked fact that the different Mayance languages have three distinct root-words for moon. In Yucatan she is called U; in Kekchí Po; in Quiché Ik' ..." (Gates)

Maybe the Polynesian Po (night) is connected to Kekchí Po (moon)?