|

TRANSLATIONS

The words of Metoro

at Bb6-13 agree well with what he said at Ab8-43:

|

|

Ab8-43 |

|

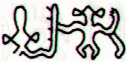

o te pito motu |

The 'cut-off' (motu)

navel string (pito) presumably indicates how at a

certain important time mother and child becomes two.

After that the feeding continues by way of nipples

(Pb3-21 and Qb4-7).

Earlier we have the similar

looking glyph as a 'crossing over place' in Mamari:

|

|

|

|

|

Ca5-17 |

Ca5-18 |

Ca5-19 |

Ca5-20 |

|

hakahagana te honu |

tagata

moe hakarava hia |

ka moe |

hakapekaga mai |

|

|

|

|

|

Ca5-21 |

Ca5-22 |

Ca5-23 |

Ca5-24 |

| te Rei |

te manu |

te

henua |

tuu te

rima i ruga |

Which reminds me of the

Hawaiian piko = 'junction of blade and stem'

(i.e. mother = stem and blade = child, I suppose):

|

Pito

1. Umbilical cord; navel;

centre of something: te pito o te henua,

centre of the world. Ana poreko te poki,

ina ekó rivariva mo uru ki roto ki te hare o

here'u i te poki; e-nanagi te pito o te

poki, ai ka-rivariva mo uru ki roto ki te

hare, when a child is born one must not

enter the house immediately, for fear of

injuring the child (that is, by breaking the

taboo on a house where birth takes place);

only after the umbilical cord has been

severed can one enter the house. 2. Also

something used for doing one's buttons up

(buttonhole?). Vanaga.

Navel. Churchill.

H Piko 1. Navel,

navel string, umbilical cord. Fig. blood

relative, genitals. Cfr piko pau 'iole,

wai'olu. Mō ka piko, moku ka piko,

wehe i ka piko, the navel cord is cut

[friendship between related persons is

broken; a relative is cast out of a family].

Pehea kō piko? How is your navel [a

facetious greeting avoided by some because

of the double meaning]? 2. Summit or top of

a hill or mountain; crest; crown of the

head; crown of the hat made on a frame (pāpale

pahu); tip of the ear; end of a rope;

border of a land; center, as of a fishpond

wall or kōnane board; place where a

stem is attached to the leaf, as of taro. 3.

Short for alopiko. I ka piko nō

'oe, lihaliha (song), at the belly

portion itself, so very choice and fat. 4. A

common taro with many varieties, all with

the leaf blade indented at the base up to

the piko, junction of blade and stem.

5. Design in plaiting the hat called

pāpale 'ie. 6. Bottom round of a

carrying net, kōkō. 7. Small wauke

rootlets from an old plant. 8. Thatch above

a door. 'Oki i ka piko, to cut this

thatch; fig. to dedicate a house. Wehewehe. |

We have also collected all glyphs where Metoro said pito:

|

|

|

|

|

Bb3-41 |

Bb6-13 |

Bb7-26 |

|

mai tae vere hia - ki te

pito o te

henua |

kua motu

te pito

o te fenua |

kua aga ko

te pito |

|

|

|

|

|

Ab8-43 |

Aa4-38 |

Aa4-39 |

|

o te

pito motu |

ki te

henua - ki uta ki te

pito o te

henua |

I was making an effort to write about GD14 (henua ora)

in the glyph dictionary, a topic very close to

te pito, because both their important times are

located at the 'end'.

Indeed, I therefore think this might be the proper place to

document what I have written about henua ora:

|

A few preliminary

remarks and imaginations:

1. This

type of glyph appears to have connections with life and death, or

more precisely with the miracle of

growth.

"When the man, Ulu,

returned to his wife from his visit to the temple at Puueo,

he said, 'I have heard the voice of the noble Mo'o, and he

has told me that tonight, as soon as darkness draws over the sea and

the fires of the volcano goddess, Pele, light the clouds over

the crater of Mount Kilauea, the black cloth will cover my

head. And when the breath has gone from my body and my spirit has

departed to the realms of the dead, you are to bury my head

carefully near our spring of running water. Plant my heart and

entrails near the door of the house. My feet, legs, and arms, hide

in the same manner. Then lie down upon the couch where the two of us

have reposed so often, listen carefully throughout the night, and do

not go forth before the sun has reddened the morning sky. If, in the

silence of the night, you should hear noises as of falling leaves

and flowers, and afterward as of heavy fruit dropping to the ground,

you will know that my prayer has been granted: the life of our

little boy will be saved.' And having said that, Ulu fell on

his face and died.

His wife sang a dirge of lament,

but did precisely as she was told, and in the morning she found her

house surrounded by a perfect thicket of vegetation. 'Before the

door,' we are told in Thomas Thrum's rendition of the legend, 'on

the very spot where she had buried her husband's heart, there grew a

stately tree covered over with broad, green leaves dripping with dew

and shining in the early sunlight, while on the grass lay the ripe,

round fruit, where it had fallen from the branches above. And this

tree she called Ulu (breadfruit) in honor of her husband.

The little spring was concealed by

a succulent growth of strange plants, bearing gigantic leaves and

pendant clusters of long yellow fruit, which she named bananas. The

intervening space was filled with a luxuriant growth of slender

stems and twining vines, of which she called the former sugar-cane

and the latter yams; while all around the house were growing little

shrubs and esculent roots, to each one of which she gave an

appropriate name. Then summoning her little boy, she bade him gather

the breadfruit and bananas, and, reserving the largest and best for

the gods, roasted the remainder in the hot coals, telling him that

in the future this should be his food. With the first mouthful,

health returned to the body of the child, and from that time he grew

in strength and stature until he attained to the fulness of perfect

manhood.

He became a mighty warrior in those days, and was

known throughout all the island, so that when he died, his name,

Mokuola, was given to the islet in the bay of Hilo where

his bones were buried; by which name it is called even to the

present time." (Campbell)

|

|

2. Growth

is always a kind of

rebirth and rebirth implies that somebody has to die first.

Without death the world would be overcrowded.

"And they were sacrificed and buried. They were

buried at the Place of Ball Game Sacrifice, as it is called. The

head of One Hunaphu was cut off; only his body was buried

with his younger brother. 'Put his head in the fork of the tree that

stands by the road', said One and Seven Death.

And when his head was put in the fork of the tree, the tree bore

fruit. It would not have had any fruit, had not the head of

One Hunaphu been put in the fork of the

tree. This is the calabash, as we call it today, or 'the skull of

One Hunaphu', as it is said. And then

One and Seven Death were amazed at the

fruit of the tree. The fruit grows out everywhere, and it isn't

clear where the head of

One Hunaphu is; now it looks just the way

the calabashes look. All the

Xibalbans see this, when they come to

look."

(Popol

Vuh)

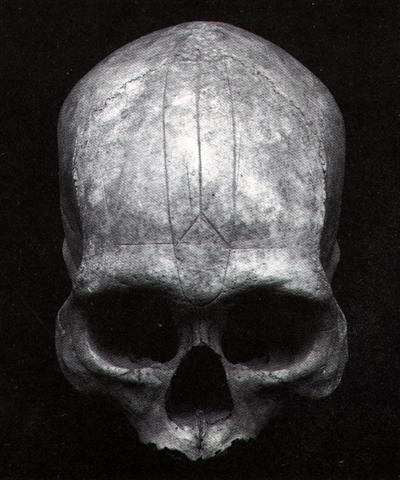

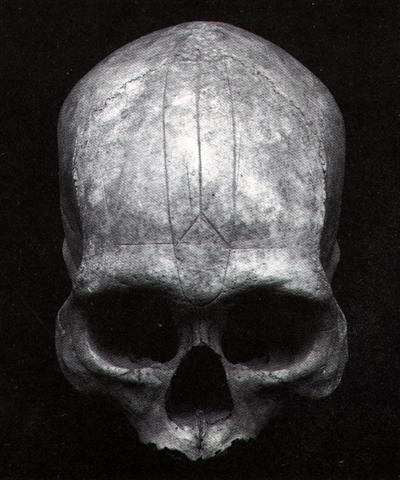

Rapa Nui

cranium (USNM 31064a) according to Van Tilburg |

|

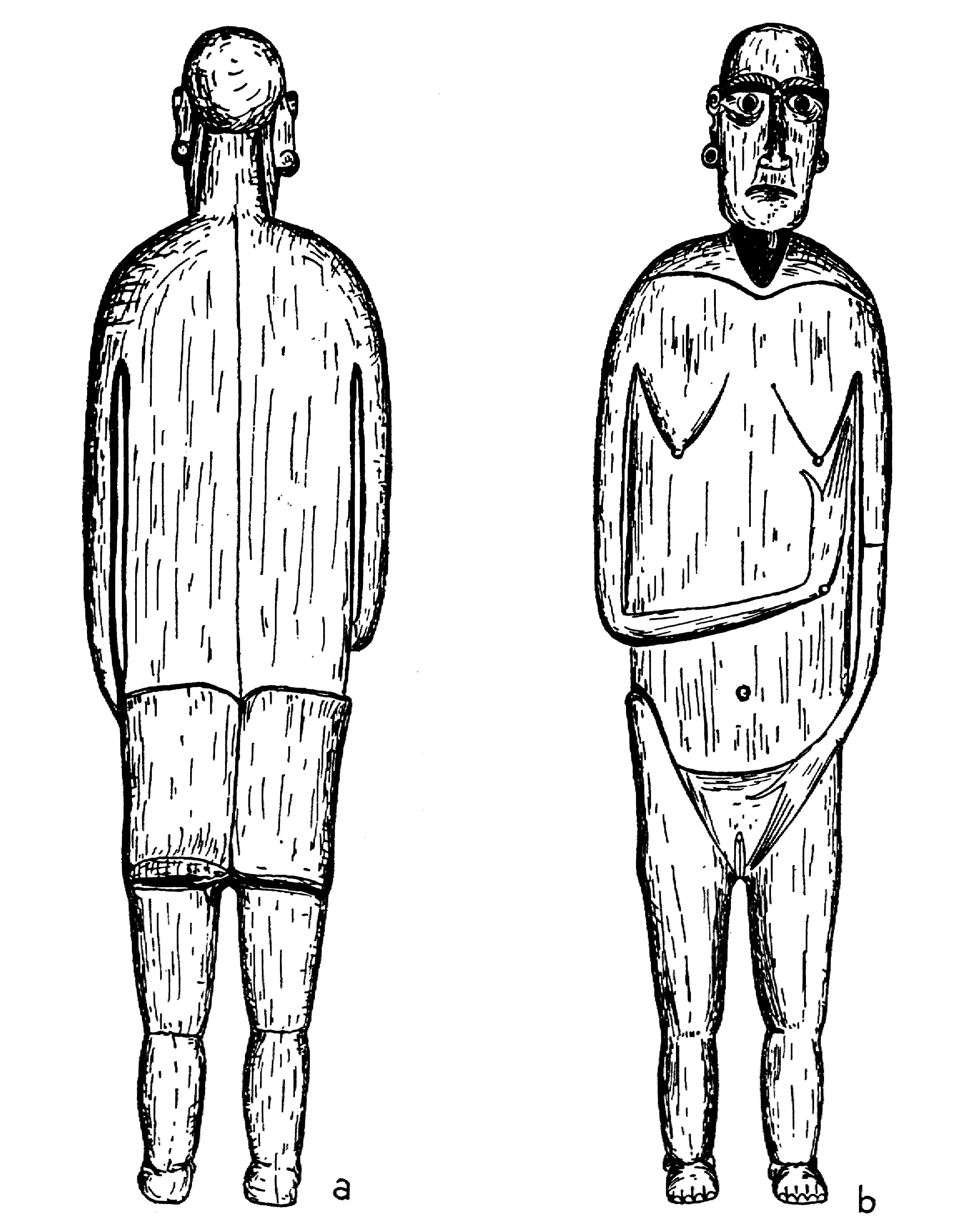

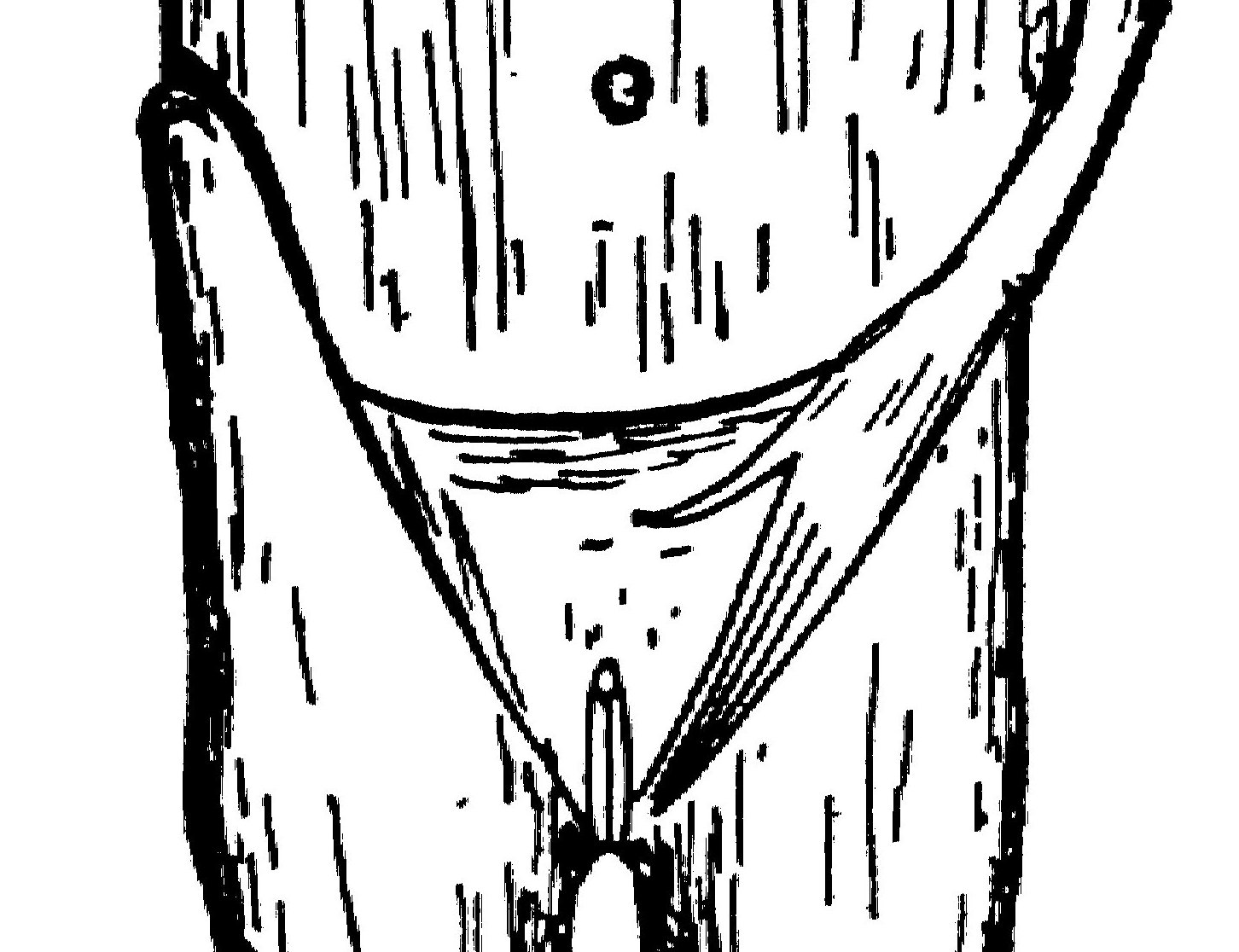

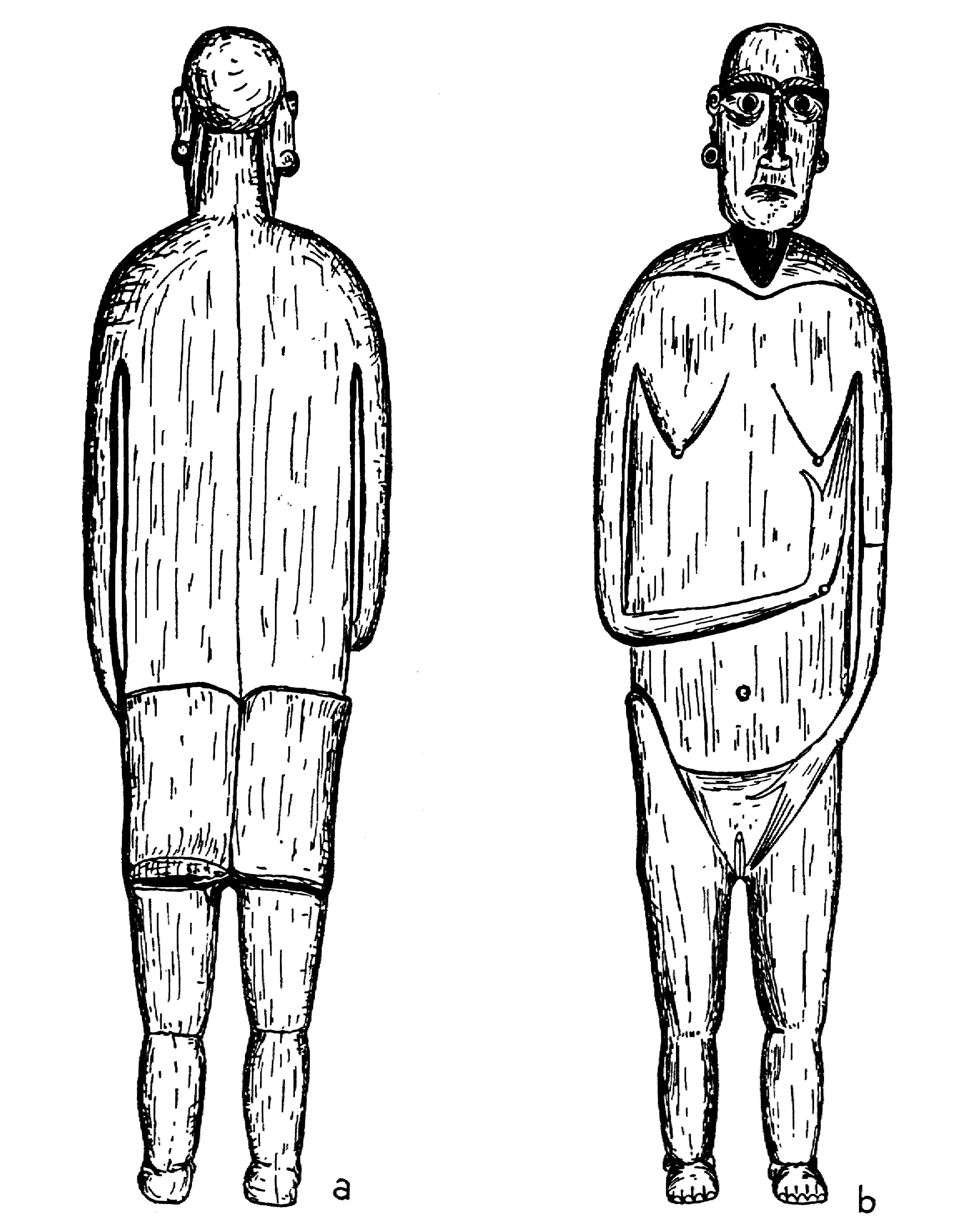

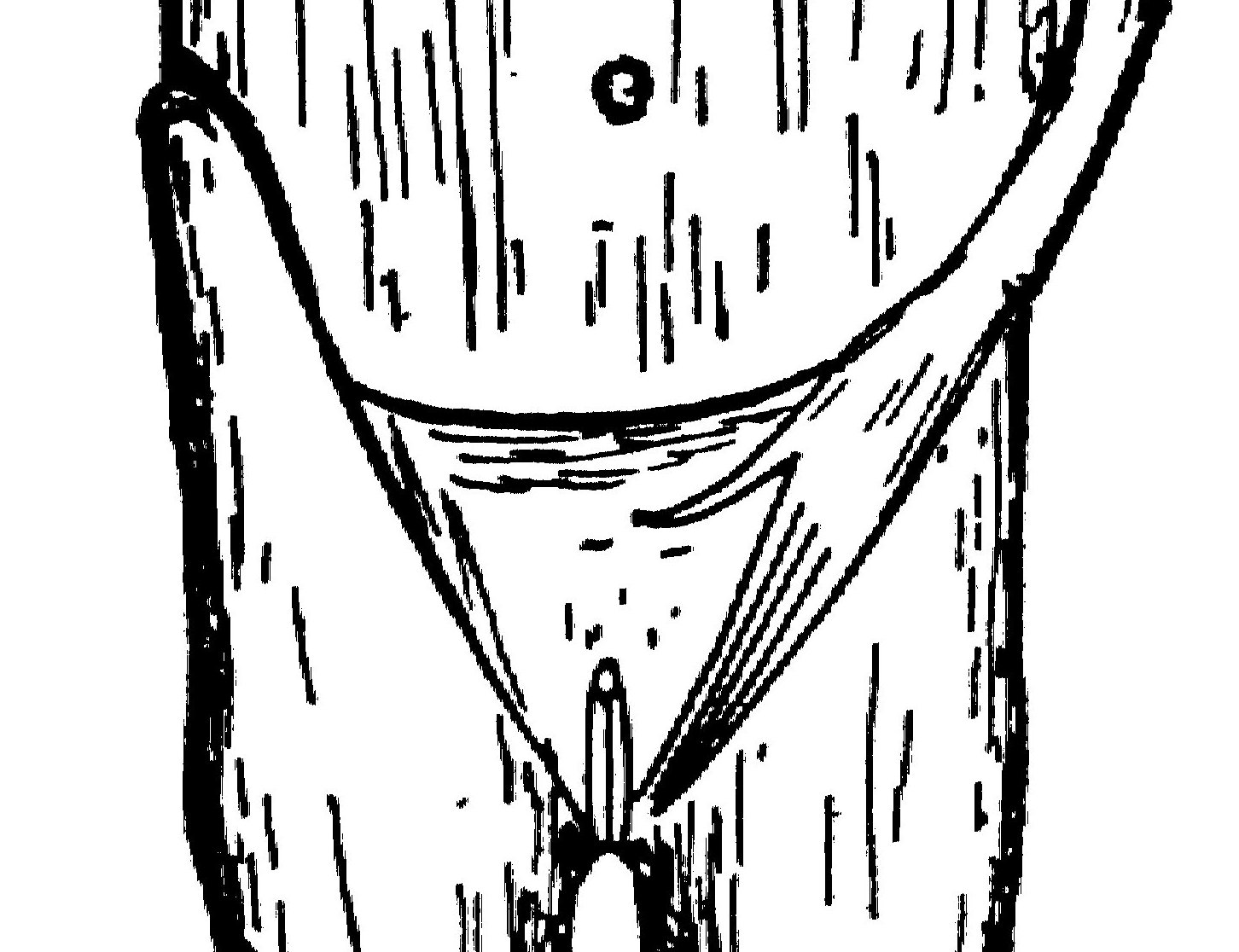

3. In this picture of a moai paapaa (ref. Métraux) we can see

that the creator has used what looks like an upside down version of GD14 as a

picture for the vulva:

The uterus is the origin of new life (ora),

and we can therefore understand Metoro when he said henua ora rua

(rua = two)

at Ab6-91--92:

A mother is equal to the fertile and living earth (henua

ora),

while man contrariwise must represent death (by being a warrior).

A preliminary assessment of the meaning of GD14 glyphs is that we

see an upside down

vulva. The GD14 glyphs are nearly always oriented this way. |

|

4. GD14 presumably shows a

kind of 'nut' at the bottom, from which

new growth emerges. This 'nut' must be 'broken' in order to free the

new life, 'breaking

the nut'.

"...in the ceremonial course of

the coming year, the king is symbolically transposed toward the

Lono pole of Hawaiian divinity; the annual cycle tames the

warrior-king in the same way as (e.g.) the Fijian installation

rites. It need only be noticed that the renewal of kingship at the

climax of the Makahiki coincides with the rebirth of nature.

For in the ideal ritual calendar, the kali'i battle follows

the autumnal appearance of the Pleiades, by thirty-three days - thus

precisely, in the late eighteenth century, 21 December, the winter

solstice. The king returns to power with the sun.7

7

The correspondence between the winter solstice and the kali'i

rite of the Makahiki is arrived at as follows: ideally, the

second ceremony of 'breaking the coconut', when the priests assemble

at the temple to spot the rising of the Pleiades, coincides with the

full moon (Hua tapu) of the twelfth lunar month (Welehu). In

the latter eighteenth century, the Pleiades appear at sunset on 18

November. Ten days later (28 November), the Lono effigy sets

off on its circuit, which lasts twenty-three days, thus bringing the

god back for the climactic battle with the king on 21 December, the

solstice (= Hawaiian 16 Makali'i). The correspondence is

'ideal' and only rarely achieved, since it depends on the

coincidence of the full moon and the crepuscular rising of the

Pleiades.

Whereas, over the next two days,

Lono plays the part of the sacrifice. The Makahiki

effigy is dismantled and hidden away in a rite watched over by the

king's 'living god', Kahoali'i or

'The-Companion-of-the-King', the one who is also known as

'Death-is-Near' (Koke-na-make). Close kinsman of the king as

his ceremonial double, Kahoali'i swallows the eye of the

victim in ceremonies of human sacrifice (condensed symbolic trace of

the cannibalistic 'stranger-king').

The 'living god', moreover, passes

the night prior to the dismemberment of Lono in a temporary

house called 'the net house of Kahoali'i', set up before the

temple structure where the image sleeps. In the myth pertinent to

these rites, the trickster hero - whose father has the same name (Kuuka'ohi'alaki)

as the Kuu-image of the temple - uses a certain 'net of

Maoloha' to encircle a house, entrapping the goddess Haumea;

whereas, Haumea (or Papa) is also a version of

La'ila'i, the archetypal fertile woman, and the net used to

entangle her had belonged to one Makali'i, 'Pleiades'.

Just so, the succeeding

Makahiki ceremony, following upon the putting away of the god,

is called 'the net of Maoloha', and represents the gains in

fertility accruing to the people from the victory over Lono.

A large, loose-mesh net, filled with all kinds of food, is shaken at

a priest's command. Fallen to earth, and to man's lot, the food is

the augury of the coming year. The fertility of nature thus taken by

humanity, a tribute-canoe of offerings to Lono is set adrift

for Kahiki, homeland of the gods.

The New Year draws to a close. At the next full moon,

a man (a tabu transgressor) will be caught by Kahoali'i and

sacrificed. Soon after the houses and standing images of the temple

will be rebuilt: consecrated - with more human sacrifices - to the

rites of Kuu and the projects of the king."

(Islands

of History) |

|

5.

The three more or less

vertical lines in GD14 may be seen as the rays of the sun and the

'nut' at the bottom is perhaps covered with earth formed like a

little hill, therefore the double wedge.

"Ta'aroa tahi tumu,

'Ta'aroa origl. stock' - most commonly Ta'aroa or

Te Tumu - existed before everything except of a rock (Te Papa)

which he compressed and begat a daughter (Ahuone) that is

Vegetable Mole.*

* Ahuone means

'earth heaped up' - a widespread name for the Polynesian first

woman. It sounds as if Cook also heard the term applied to the banks

of humus and rotting material on which taro is grown. In the

English of his day this was known as 'vegetable mould'."

(Record by Captain Cook. Ref.: Legends of the South Seas.)

Death and rebirth

are so fundamental and difficult to understand that we here must

continue with more explanations. Dr. Jung (ref. Campbell) seems to

be the best authority in our civilization:

"Do we ever understand what we think? We understand

only such thinking as is a mere equation and from which nothing

comes out but what we have put in. That is the manner of working of

the intellect. But beyond that there is a thinking in primordial

images - in symbols that are older that historical man; which have

been ingrained in him from earliest times, and, eternally living,

outlasting all generations, still make up the groundwork of the

human psyche. It is possible to live the fullest life only when we

are in harmony with these symbols; wisdom is a return to them. It is

a question neither of belief nor knowledge, but of the agreement of

our thinking with the primordial images of the unconscious. They are

the source of all our conscious thoughts, and one of these

primordial images is the idea of life after death."

"A human being would certainly not grow to be seventy

or eighty years old if this longevity had no meaning for the species

to which he belongs. The afternoon of human life must have a

significance of its own and cannot be merely a pitiful appendage to

life's morning.

The significance of the morning undoubtedly lies in

the development of the individual, our entrenchment in the outer

world, the propagation of our kind and the care of our children. But

when this purpose has been attained - and even more than attained -

shall the earning of money, the extension of conquests, and the

expansion of life go steadily on beyond the bounds of all reason and

sense?

Whoever carries over into the afternoon the law of

the morning - that is, the aims of nature - must pay for so doing

with damage to his soul just as surely as a growing youth who tries

to salvage his childish egoism must pay for this mistake with social

failure.

Moneymaking, social existence, family and posterity

are nothing but plain nature - not culture. Culture lies beyond the

purpose of nature. Could by any chance culture be the meaning and

purpose of the second half of life? In primitive tribes, we observe that the old people

are almost always the guardians of the mysteries and the laws, and

it is in these that the cultural heritage of the tribe is

expressed." |

|

The

preliminary remarks and imaginations lead us to the idea that

henua ora in some way is connected with the mysteries of

life, growth, ageing and death. In the Keiti

calendar of the year henua ora appears in the 10th period (i.e. in the

6th of the 12 half-months long summer) and also in

the 1st period:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

11 |

12 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

13 |

14 |

15 |

16 |

17 |

18 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

19 |

20 |

21 |

22 |

23 |

24 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

25 |

26 |

27 |

28 |

29 |

30 |

|

These 31

glyphs evidently function as end-of-period markers in

the same way as what we have seen in the Keiti

calendar. The only difference is the

'feathers' (meaning 'end'). |

|

31 |

|

Here

(left) is the last (32nd) end-of-period marker, a special design

- as there also is a special design in the 24th and last end-of-period marker in

Keiti (right). |

|

|

Ga7-14 |

Eb6-19 |

|

|

Next I chose

the 19th period of G and can see two parallel sequences of

glyphs in Keiti:

|

|

Autumn equinox in E should be located in the 18th period:

|

|

We can now try again with the table of comparison:

|

|

The glyphs tell us more. Important is to notice how already in

the 15th period the coming dark half of the year is defined:

|

15 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Ga4-23 |

Ga4-24 |

Ga4-25 |

Ga4-26 |

Ga4-27 |

6 + 6

= 12 half-months (representing the dark two quarters) are visualized

by wedge-marks inside the perimeters of the ovals in Ga4-23--24.

Autumn equinox occurs around the 21st of March (south of the

equator), i.e. before the 1st of April (when the last quarter of the

year begins). We should therefore not be surprised to find already

in the 15th period this message. Equinoxes do not occur on the 1st

of a month.

In E

the half-months are defined as 360 / 24 = 15 days. In period 15 of G

we should - therefore - read (6 + 6) * 15 = 180 days for the dark

half of the year.

|

|

The measure 180 for the winter half gives us automatically 360 -

180 = 180 days for the summer too. In G summer begins with

period no. 7 and ends with period no. 12, i.e. there are only 6

periods during summer (the same number as the number of flames

around the sun, GD12).

The length of such a summer period must be

longer than 15 days:

180 / 6 = 30

But

we can

reformulate into half-periods: 12 * 15 = 180. The winter

season may then (for harmony's sake) be formulated as:

13 * 14 = 182

12 +

15 = 13 + 14. Furthermore 13 and 14 are

inside 12 and 15, suggesting that

13 and 14 are female in character.

365 -

180 - 182 = 3. There are signs that the rongorongo creators thought

about 3 dark nights at the end of a year. A working hypothesis is

therefore that the calendar in G covered a whole year.

|

|

"They walked

in crowds when they arrived at Tulan, and there was no fire.

Only those with Tohil had it: this

was the tribe whose god was first to generate fire. How it was

generated is not clear. Their fire was already burning when

Jaguar Quitze and Jaguar Night

first saw it: 'Alas! Fire has not yet become ours. We'll die from

the cold', they said. And then Tohil spoke: 'Do not grieve.

You will have your own even when the fire you're talking about has

been lost', Tohil told them.

'Aren't you a true god! Our

sustenance and our support! Our god!' they said when they gave

thanks for what Tohil had said.

'Very well, in truth, I am your

god: so be it. I am your lord: so be it,' the penitents and

sacrificers were told by Tohil.

And this was the warming of the

tribes. They were pleased by their fire.

After that a

great downpour began, which cut short the fire of the tribes. And

hail fell thickly on all the tribes, and their fires were put out by

the hail. Their fires didn't start up again. So then

Jaguar Quitze and Jaguar Night

asked for their fire again: 'Tohil,

we'll be finished off by the cold', they told Tohil. 'Well, do not grive', said

Tohil. Then he started a fire. He

pivoted inside his sandal." (Popol Vuh)

|

|

Already at

the beginning of the 'solar canoe' voyage the destination is

known. How else could the (straight) courses between the turning

(cardinal) points be defined? Already at birth the final

destination is know - death. Henua ora

is the final destination. In the frame of reference in form of a

canoe voyage it is the ultimate harbour

which governs the journey. In the frame of reference in form of a

journey of life it means

death, where 'earth' (mother nature) is the

receptacle.

Movement is

cyclical:

|

"... 'The

rays drink up the little waters of the earth, the

shallow pools, making them rise, and then descend again

in rain.' Then, leaving aside the question of water, he

summed up his argument: 'To draw up and then return what

one had drawn - that is the life of the world' ..."

(Ogotemmêli) |

Henua ora

is designed to be a kind of cup (receptacle). |

|

'There was noise at

night at Marioro, it was Hina beating tapa in

the dark for the god Tangaroa, and the noise of her mallet

was annoying that god, he could endure it no longer. He said to

Pani, 'Oh Pani, is that noise the beating of tapa?'

and Pani answered, 'It is Hina tutu po beating

fine tapa.'

Then Tangaroa

said, 'You go to her and tell her to stop, the harbour of the god is

noisy.' Pani therefore went to Hina's place and said

to her, 'Stop it, or the harbour of the god will be noisy.' But

Hina replied, 'I will not stop, I will beat out white tapa

here as a wrapping for the gods Tangaroa, 'Oro, Moe,

Ruanu'u, Tu, Tongahiti, Tau utu, Te

Meharo, and Punua the burst of thunder'.

So Pani returned and told the god that Hina would not

stop.

'Then go to her again', said Tangaroa, 'and make her stop.

The harbour of the god is noisy!' So Pani went again, and he

went a third time also, but with no result. Then Pani too

became furious with Hina, and he seized her mallet and beat

her on the head. She died, but her spirit flew up into the sky, and

she remained forever in the moon, beating white tapa. All may

see her there. From that time on she was known as Hina nui aiai i

te marama, Great-Hina-beating-in-the-Moon." (World of the

Polynesians) |

|

"My son, said Makea tutara

one evening at dusk, when they were sitting outside the house, I

have heard from your mother and from others that you are brave and

capable, and that in everything you have undertaken in your own

country you have succeeded. That says a great deal for you. But I

have to warn you: now that you have come to live in your father's

country you will find that things are different. I am afraid that

here you may meet your downfall at last. 'What do you mean?' said

Maui. 'What things are there here that could be my downfall?'

'There is your great ancestress

Hine nui te Po', said Makea, gravely. And he

watched Maui's face as he mentioned the name of

Great Hine the Night, the daughter and the

wife of Tane and goddess of death. But Maui did not

move an eyelid. 'You

may see her, if you look', Makea went on, pointing to where

the sun had gone down, 'flashing over there, and opening and

closing, as it were'. His thoughts were on death as he spoke. For it

was the will of Hine nui, ever since she turned her back on

Tane and descended to Rarohenga, that all her

descendants in the world of light should follow her down that same

path, returning to their mother's womb that they might be mourned

and wept for.

'Oh, nonsense', said Maui

affectionately to the old man. 'I don't think about that sort of

thing, and you shouldn't either. There's no point in being afraid.

We might just as well find out whether we are intended to die, or to

live forever.' Now Maui had not forgotten what his mother

once said about Hine nui te Po: that he would some day

vanquish her, and death would then have no power over men. He

remembered this now, and was not moved by his father's fears. But

Hine nui was the sister of Mahuika, and she knew of

Maui's dangerous trickery at the abode of fire, and was resolved

to protect her other descendants from further mischief of this kind.

'My child', said Makea now

in a tone of deep sorrow, 'there has been a bad omen for us. When I

performed the tohi ceremony over you I missed out a part of

the prayers. I remebered it too late. I am afraid this means that

you are going to die.' 'What's she like, Hine nui te Po?'

asked Maui. 'Look over there', said Makea, pointing to

the ice-cold mountains beneath the flaming clouds of sunset. 'What

you see there is Hine nui, flashing where the sky meets the

earth. Her body is like a woman's, but the pupils of her eyes are

greenstone and her hair is kelp. Her mouth is that of a barracuda,

and in the place where men enter her she has sharp teeth of obsidian

and greenstone.'

'Do you think she is as fierce as

Tama nui te ra, who burns things up by his heat?' asked

Maui. 'Did I not make life possible for man by laming him and

making him keep his distance? Was it not I who made him feeble with

my enchanted weapon? And did the sea not cover much more of the

earth until I fished up land with my enchanted hook?' 'All that is

very true', said Makea. 'And you are my last-born son, and

the strength of my old age. Very well then, be it as it will. Go

there, and visit your ancestress if that is what you wish. You will

find her there where the earth meets the sky.' And they sat for a

while in the dusk, until the red clouds turned grey and the

mountains into black.

Next morning early, Maui

went out looking for companions for the expedition. The birds were

up when he left, and among them he succeeded in finding several who

were willing to go with him. There was tiwaiwaka, the little

fantail, flickering about inquisitively and following Maui

along the track as if he might have something for him. There was

miromiro, the grey warbler, tataeko, the whitehead, and

pitoitoi, the robin, who is almost as tame and curious as the

fantail. Maui assembled a party of these friends and told

them what he intended to do. They knew it was an act of great

impiety to invade the realm of Hine nui te Po with

mischievous intentions.

And now, they learned, it was

Maui's idea to enter her very body. He proposed to pass through

the womb of Great Hine the Night,

and come out by her mouth. If he succeeded, death would no longer

have the last word with regard to man; or so his mother had told him

long ago. This, then, was to be the greatest of all his exploits.

Maui, who once

had travelled eastward to the very edge of the pit where the sun

rose, and southward over the great Ocean of Kiwa to where he

fished up land, and all the way to the dwelling-place of Mahuika

- Maui now proposed a journey to defy great Hine in

the west. Taking his enchanted weapon, the sacred jawbone of Muri

ranga whenua, he twisted its strings around his waist. Then he

went into the house and threw off his clothes, and the skin on his

hips and thighs was as handsome as the skin of a mackerel, with the

tattoed scrolls that had been carved there with the chisel of

Uetonga. And off they went, with the birds twittering in their

excitement.

When they arrived at the place

where Hine nui lay asleep with her legs apart and they could

see those flints that were set between her thighs, Maui said

to his companions: 'Now, my little friends, when you see me crawl

into the body of this old chieftainess, whatever you do, do not

laugh. When I have passed right through her and am coming out of her

mouth, then you can laugh if you want to. But not until then,

whatever you do.' His frieds twittered and fluttered about him and

flew in his way. 'O sir', they cried, 'you will be killed if you go

in there.' 'No', said Maui, holding up his enchanted jawbone.

'I shall not - unless you spoil it. She is asleep now. If you start

laughing as soon as I cross the threshold, you will wake her up, and

she will certainly kill me at once. But if you can keep quiet until

I am on the point of coming out, I shall live and Hine nui

will die, and men will live thereafter for as long as they wish.' So

his friends moved out of his way. 'Go on in then, brave Maui',

they said, 'but do take care of yourself'.

Maui

at first assumed the form of a kiore, or rat, to enter the

body of Hine. But tataeko, the little whitehead, said

he would never succeed in that form. So he took the form of a

toke, or earth-worm. But tiwaiwaka the fantail, who did

not like worms, was against this. So Maui turned himself into

a moko huruhuru, a kind of caterpillar that glistens. It was

agreed that this looked best, and so Maui started forth, with

comical movements.

The little birds now did their

best to comply with Maui's wish. They sat as still as they

could, and held their beaks shut tight, and tried not to laugh. But

it was impossible. It was the way Maui went in that gave them

the giggles, and in a moment little tiwaiwaka the fantail

could no longer contain himself. He laughed out loud, with his

merry, cheeky note, and danced about with delight, his tail

flickering and his beak snapping. Hine nui awoke with a

start. She realised what was happening, and in a moment it was all

over with Maui. By the way of rebirth he met his end.

Thus died this Maui we have

spoken of, who was formed in the topknot of Taranga and cast

in the sea, but was saved and nurtured to lead a life of mischief.

And thus did the laughter of his companions at the last and most

scandalous of his exploits deprive mankind of immortality. For

Hine nui always knew what Maui had it in mind to do to

her. But she knew that it was best that man should die, and return

to the darkness from which he comes, down that path which she made

to Rarohenga. Wherefore our people have the saying: 'Death

came to the mighty when Maui was strangled by Hine nui to

Po, and so it has remained in the world'."

(Maori Myths) |

|

"12. Odysseu's arrival home: Transformed by

Athene into the semblance of a beggar (Noman, still), the returned

master of the house was recognized only by his dog and his old, old

nurse. The latter spied above his knee the old scar of a gash

received from the tusk of a boar. (Compare Adonis and the boar,

Attis and the boar, and, in Ireland, Diarmuid and the boar.) Hushing

the nurse, Odysseus watched for some time the shameless behavior of

the suitors and maidservants in his house; whereafter, and at last:

13. Penelope, offering to marry any one of those

present who could draw the powerful bow of her spouse, set up a

target of twelve axes to be pierced. None of the suitors

could even string the bow. Several tried manfully. The recently come

beggar then offered and was mocked. However, as we read:

He already was handling

the bow, turning it every way about, and proving it on this side and

that, lest the worms might have eaten the horns when the lord of the

bow was away...

And Odysseus of many

counsels had lifted the great bow and viewed it on every side, and

even as when a man that is skilled in the lyre and in minstralsy,

easily stretches a cordabout a new peg, after tying at either end

the twisted sheep-gut, even so Odysseus straightway bent the great

bow, all without effort, and took it in his right hand and proved

the bowstring, which rang sweetly at the touch, in tone like a

swallow.

Then great grief came

upon the wooers, and the color of their countenance was changed, and

Zeus thundered loud showing forth his tokens. And the steadfast

goodly Odysseus was glad thereat, in that the son of

deep-counselling Cronus had sent him a sign.

Then he caught up a

swift arrow which lay by his table, bare, but the other shafts were

stored within the hollow quiver, those whereof the Achaeans were

soon to taste.

He took and laid it on

the bridge of the bow, and held the notch and drew the string, even

from the settle whereupon he sat, and with straight aim shot the

shaft and missed not one of the axes, beginning from the first

ax-handle, and the bronze-weighted shaft passed clean through and

out at the last.

The solar hero having thus demonstrated his

passage of the twelve signs and his lordship of the palace, he

proceeded masterfully to the shooting down of the suitors. 'And they

writhed with their feet for a little space, but for no long while.'

After which, 'Thy bed verily shall be ready,' said

the wisely wifely Penelope. 'Come tell me of thine ordeal. For

methinks the day will come when I must learn it, and timely

knowledge is no hurt'." (Campbell 3)

|

|

"... the name [Vindler,

one of the epithets of Heimdall] is a subform of vindill

and comes from vinda, to twist or turn, wind, to turn

anything around rapidly. As the epithet 'the turner' is given to

that god who brought friction-fire (bore-fire) to man, and who is

himself the personification of this fire, then it must be synonymous

with 'the borer' ...

The Sibyl's prophecy

does not end with the catastrophes, but it moves from the tragic to

the lydic mode, to sing of the dawning of the new age:

Now do I see / the Earth anew / Rise all green / from the waves

again ... / Then fields unsowed / bear ripened fruit / All ills grow

better."

(Hamlet's Mill) |

|

To summarize:

While rei miro signifies a 'canoe' which is turning

around, in order to begin a new straight course, henua ora

is at the opposite end of the 'travel'. The turning around

the 'canoe' is a shaky operation which takes place before the next

phase of the travel can begin. Therefore we find rei miro

immediately before the new straight course (= season in the

calendar).

At the final end

of the 'travel', beyond the 'full stop', henua ora is

located. There is no more movement and the 'canoe' is in its

harbour. The canoe is 'sleeping'.

We therefore find

henua ora immediately after the last straight course (=

season in the calendar). |

|