|

TRANSLATIONS

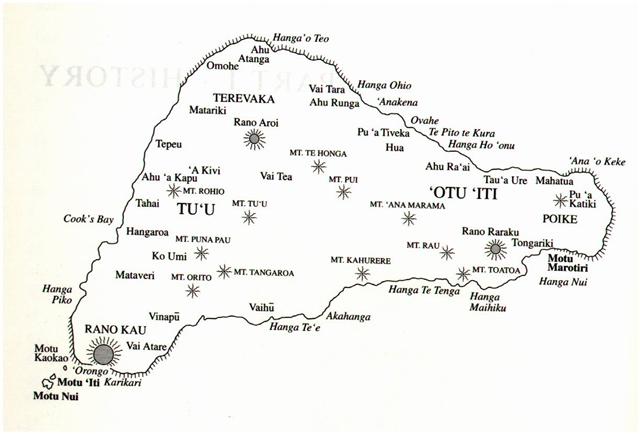

For the moon (kuhane) arriving at the 28th station (Ahu Akapu) means the last station of the cycle, while for the sun (Hau Maka) - having moved in the opposite direction (clockwise) - Ahu Akapu, at the midpoint of the west coast, also must mean the end of the travel: ... When the king of Papa O Pea has assembled his people (?) and has come to this place, he reaches Aha Akapu. To stay there, to remain (for the rest of his life) at Ahu Akapu, the king will abdicate (?) as soon as he has become an old man' ... The beginning of the moon journey is the three islets outside Orongo, while the sun presumably starts at Anakena (the first month of the year). The paepae (west coast) is the dark prebeginnings for both moon and sun. A little while ago I suggested that the back side of Ahu Tepeu was a wall connected with winter solstice, and that the 3 uprights alluded to the 3 wives (seasons) of the sun:

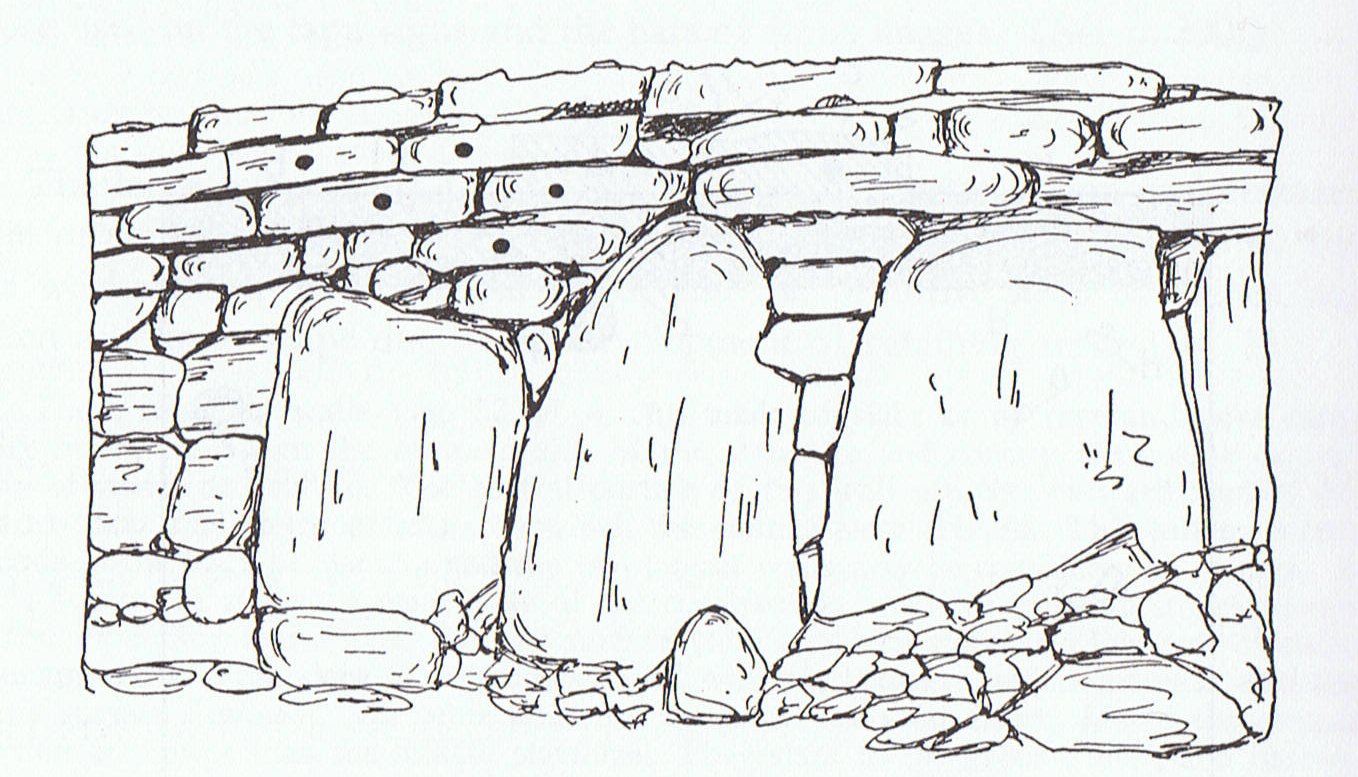

I have no reason to change that opinion, but another idea, that GD11 has a form similar to the ahu sites, cannot be right: ... The wings [of Ahu Haga O Hônu] make me imagine the whole structure as an architectual representation of GD11:

The head corresponds to the red 'hats' (tikitiki?) of the moai erected highest on the stage ... The head of GD11 is not located at the wall of the ahu, it is raised high against the sky. The moai are vertically raised props (toko), they are opposite to papa (horizontal flat). The head in GD11 is looking right, from us seen. The rongorongo text is also flowing in that direction. When we observe the sun moving towards west we think 'male' if we regard the movement towards west as being towards right. But if sun is male, then he must move towards his right. Which means that we should observe the movement as going towards left. We observe his movement by looking towards him, not by turning our back towards him. As to the journey of the kuhane we have no such problem. We imagine us looking down from the sky onto Easter Island and can observe the counterclockwise movement as going towards left. If we try something similar with the rongorongo boards, then we observe the text flowing first to the right, then turning half way around counterclockwise. Next turn, though, is clockwise. We have alternating motion, just as in Angkor:

When sun is observed in his yearly cycle, he goes to the solstice point and then reverses to move to the opposite solstice point, then he once again reverses. That is the fundamental alternative motion in the sky. The moon also exhibits an alternative motion, it may be imagined, because the movement oscillates between maximum (full moon) and minimum (new moon) in the same way. The flow of the rongorongo text, therefore, does not express any sign of being modelled after the sun or after the moon. Sun and moon both move alternatively and their is no distinction in that regard. Motu Marotiri, I guess, is connected with maro (GD67) and with the month Maro (at the end of the year). If that is correct, then probably sun travels from Anakena to Motu Marotiri during the first 3 seasons (wives). Because once long ago the last (4th) season (Maui pae) appeared to be without sun. The last quarter of the solar year would then be from Marotiri westwards along the coast up to the 3 islets outside Orongo. From Orongo up the west coast to Vai Poko and Anakena could then as now have been regarded as outside the regular calendar. This idea would explain why in the day calendar sun obviously is absent in the latter half of p.m.:

To continue: Maui taha ruled up to Marotiri. From Anakena to Marotiri the 3 wives (Maui muri, Maui roto and Maui taha) probably shared equally the path of the sun so that each one got 1/3 (i.e. 1 quarter). The center (Maui roto) must therefore lie on the north coast of Easter Island, not at Poike. To continue: Maui taha (at the side) is the last (oldest) phase of the visible and present sun. Maybe that explains why the frigate bird sometimes was called taha. The life of the sun begins with him arriving at 'dawn' in a canoe, he eats and grows and at 'noon' is experiencing his initiation to grownup life. From that point onwards he is a 'warrior' and takes on the habits of the frigate bird. "... Formerly, a young man could not marry before completing the cycle of the initiation rites and thus attaining the status of penp, 'warrior' ..." (From Honey to Ashes) "There are five species in the family Fregatidae, the frigatebirds. They are very closely related, and are all in the single genus Fregata. Frigatebirds attack other sea birds, hence the name. They are also sometimes called Man of War birds or Pirate birds. Since they are related to the pelicans, the term 'frigate pelican' is also a name applied to them. Frigatebirds are large, with iridescent black feathers (the females have a white underbelly), with long wings (male wingspan can reach 2.3 metres) and deeply-forked tails. The males have inflatable red-coloured throat pouches called 'gula pouches', which they inflate to attract females during the mating season. Frigatebirds are found over tropical oceans and ride warm updrafts. Therefore, they can often be spotted riding weather fronts and can signal changing weather patterns. These birds do not swim and cannot walk well, and cannot take off from a flat surface. Having the largest wingspan to body weight ratio of any bird, they are essentially aerial, able to stay aloft for more than a week, landing only to roost or breed on trees or cliffs. They lay one or two white eggs. Both parents take turns feeding for the first three months but then only the mother feeds the young for another eight months. It takes so long to rear a chick that frigatebirds cannot breed every year. It is typical to see juveniles as big as their parents waiting to be fed. When they sit waiting for endless hours in the hot sun, they assume an energy-efficient posture in which their head hangs down, and they sit so still that they seem dead. But when the parent returns, they will wake up, bob their head, and scream until the parent opens its mouth. The hungry juvenile plunges its head down the parent's throat and feeds at last. As members of Pelecaniformes, frigatebirds have the key characteristics of all four toes being connected by the web, a gular sac (also called gular skin), and a furcula that is fused to the breastbone. Although there is definitely a web on the frigatebird foot, the webbing is reduced and part of each toe is free. Frigatebirds produce very little oil and therefore do not land in the ocean. The gular sac is used as part of a courtship display and is, perhaps, the most striking frigatebird feature." (Wikipedia) During the 3rd season from midsummer up to decapitation at autumn equinox sun is taha. During the first 2 seasons sun is still in his childhood, he is not ready to fly high, he is a moa. In Métraux we find an important observation as regards the shape of the old stone fishhooks:

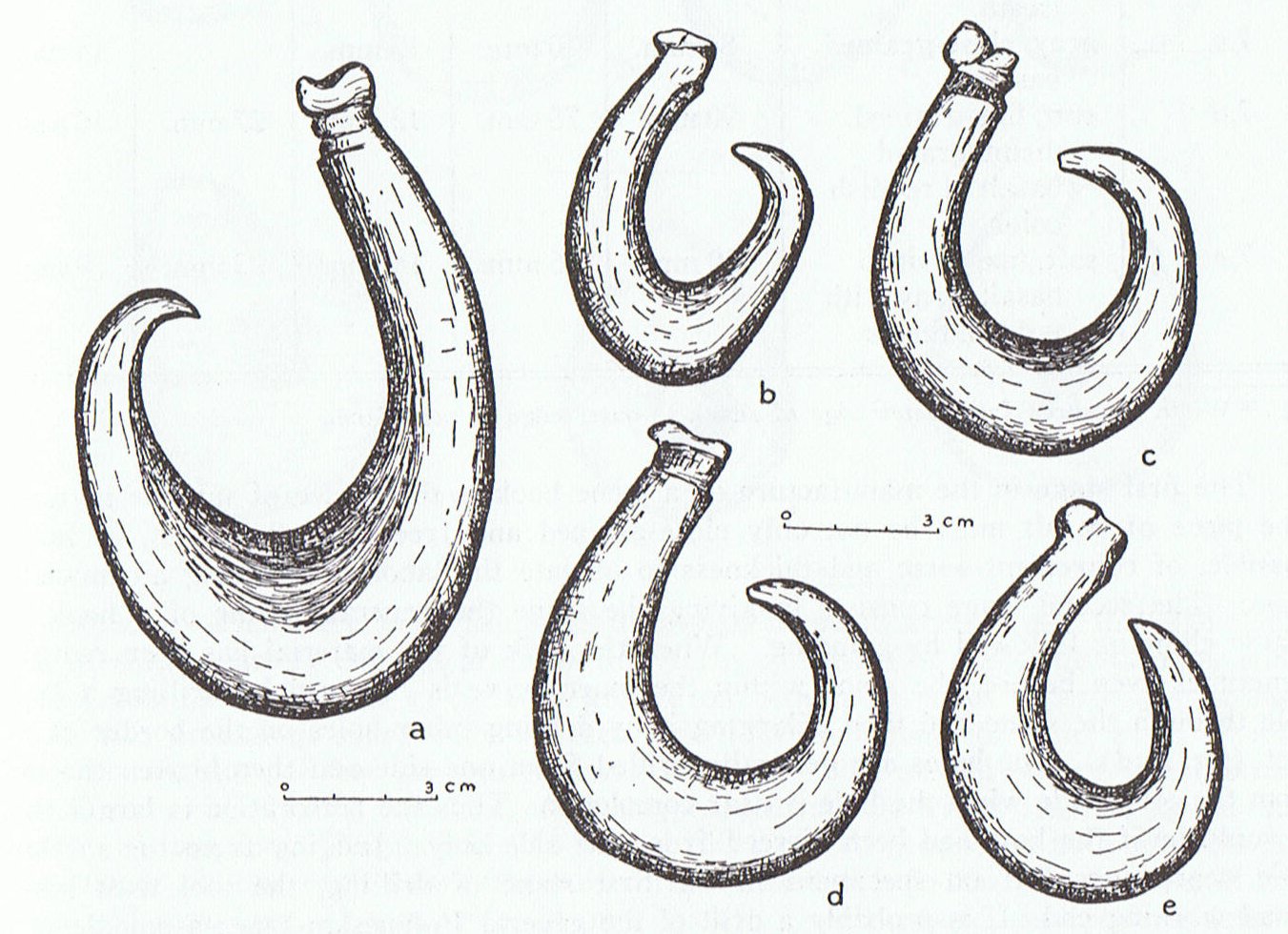

"The pattern of the stone hooks is uniform throughout, the principal variations being in thickness at the bend and in the distance between the point and the shank. Most of the fishhooks have a continous curve, but in one specimen [b] ... the limb from the bend to the point is almost straight. The shank is topped by a knob or projecting ridge with transverse grooves. A depression in the knob divides it into two unequal parts - one rounded, and the other small and sharp ... which is generally toward the point. Below the ridge there is a recess, the inner margin of which is sometimes serrated. The knob so divided strongly resembles the outlines of birds' heads as represented on the tablets." I guess that Métraux refers to such birds' heads as in for instance (Ab7-39):

I have decided to name GD32 glyphs hakaturou, but an alternative which also was suggested by Metoro's words at these glyphs was moa. He never said hakaturou at the straight GD32 glyphs, just at curved ones, while moa was used at straight or 'elbow' glyphs, e.g. Ab5-24 and Aa1-8:

Somewhat disturbing is the fact that I have chosen a straight GD32 variant as norm, while the name hakaturou suggests a bent form (and hakaturu means 'to cause to descend'):

The moa (as I guess) represent the stations of the sun during a.m. (before midsummer). They push the sky up. They, rather than the taha stage, express the same function as the great statues (moai). We should draw the conclusion that moai is to be read as moaî, where î means the same thing as in Vakaî, i.e. superlative (to abound):

|