|

TRANSLATIONS

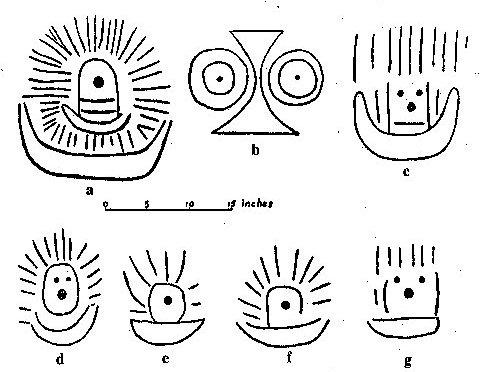

The beginning of hau tea in the glyph dictionary:

|

A few preliminary

remarks and imaginations:

1.

The beams of the sun which enlighten

our world:

presumably form the bottom part of the hau tea glyph type. This way of illustrating

- with the rays depicted as straight lines -

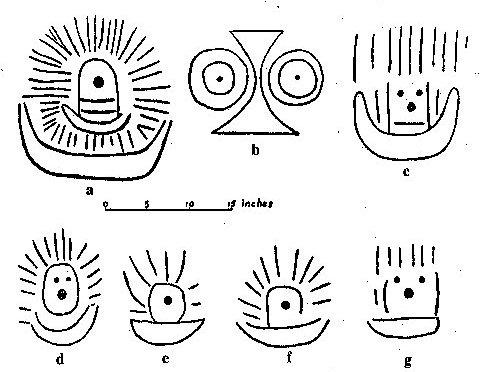

is the same as in the petroglyphs below (ref. Heyerdahl 3):

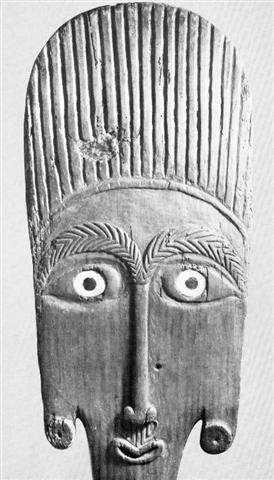

The vertical sun rays are also seen on the upper part of an example

of

ao:

:

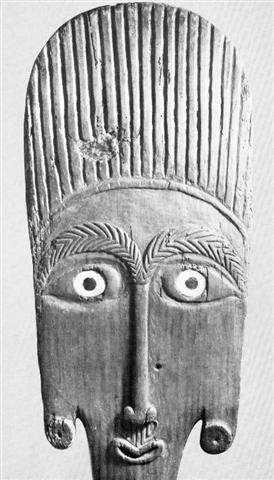

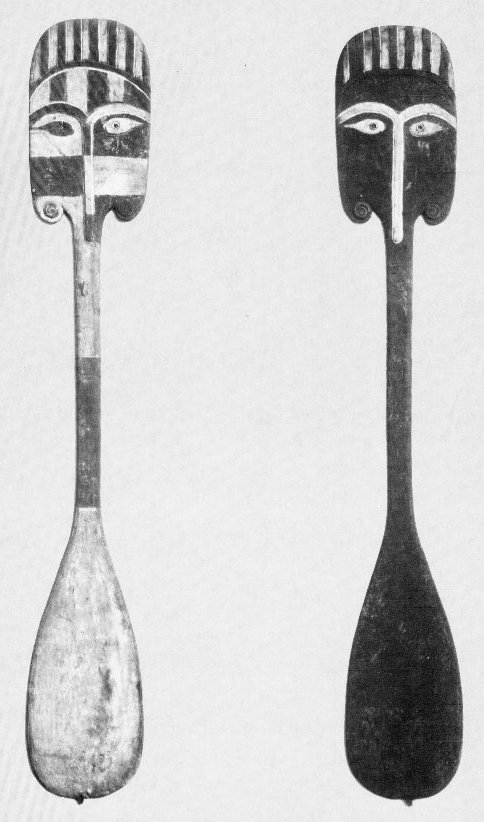

"A large portion of the upper blade, corresponding to

the broad and tall forehead, is covered by dense rows of vertically

painted stripes that may indicate hair although in some specimens

they definitely assume the aspects of a feather-crown of the type

common in aboriginal Easter Island." (Heyerdahl 3) |

| Ao, aô Large dance paddle.

1. Command, power, mandate, reign: tagata

ao, person in power, in command, ruler. 2. Dusk, nightfall. 3. Ao

nui, midnight. 4. Ao popohaga, the hours between midnight and

dawn. Aô, to serve (food); ku-âo-á te kai i ruga i te kokohu,

the food is served on a platter. Vanaga.

1. Authority, kingdom, dignity, government, reign (aho);

topa kia ia te ao, reign; hakatopa ki te ao, to confer

rank; ao ariki, royalty; ka tu tokoe aho, thy kingdom

come. PS Mgv.: ao, government, reign. Mq.: ao, government,

reign, command. Sa.: ao, a title of chiefly dignity; aoao,

excellent, surpassing, supreme. 2. Spoon; ao oone, shovel. 3. Dancing club

T. 3. Aonui (ao-nui 2), midnight. 4. Pau.: ao, the

world. Mgv.: ao, id. Ta.: ao, id. Mq.: aomaama, id.

Ma.: ao, id. 5. Pau.: ao, happy, prosperity. Mgv.: ao,

tranquil conscience. Ta.: ao, happiness. 6. Mgv.: ao,

cloud, mist. Ta.: ao, id. Mq.: ao, id. Sa.: ao,

cloud. Ma.: ao, id. 7. Mgv.: ao, hibiscus. 8. Ta.: ao,

day. Mq.: ao, day from dawn to dark. Sa.:

ao, id. Ma.: ao, id. 9. Ta.: ao, a bird. Ha.: ao, id.

10. Mq.: ao, respiration, breath. Ha.: aho, breath. 11.

Mq.: ao, to collect with hand or net. Sa.: ao, to gather.

Ma.: ao, to collect. Ta.: aoaia, to collect food and other

things with care. Churchill. |

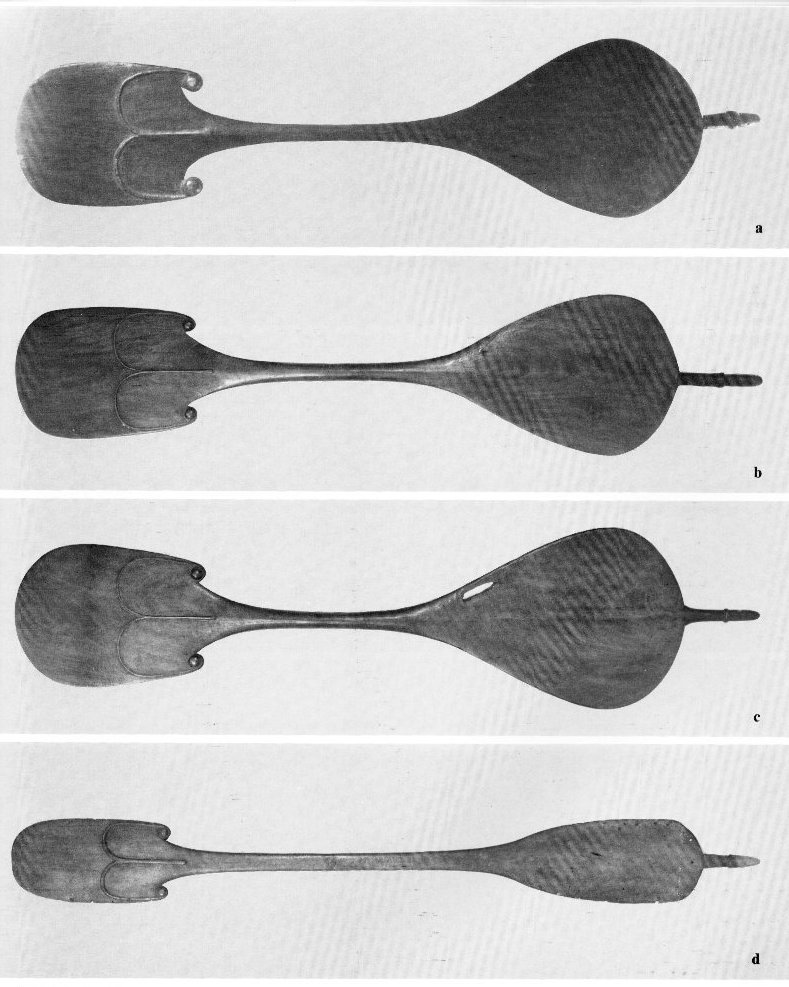

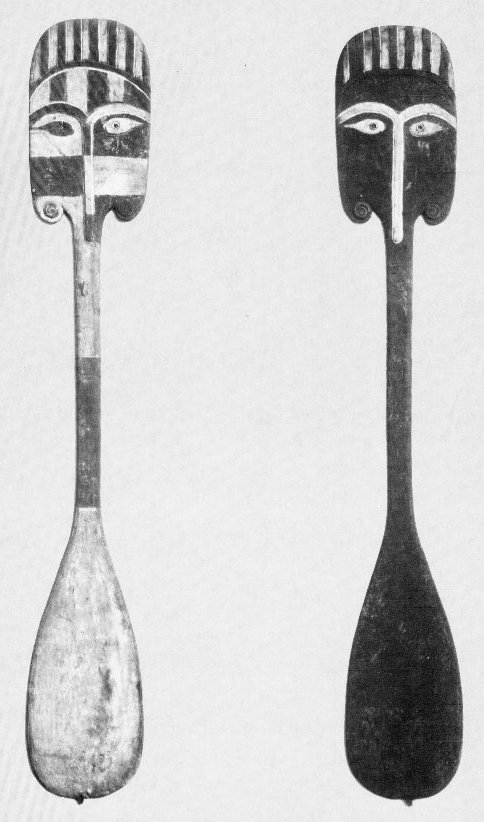

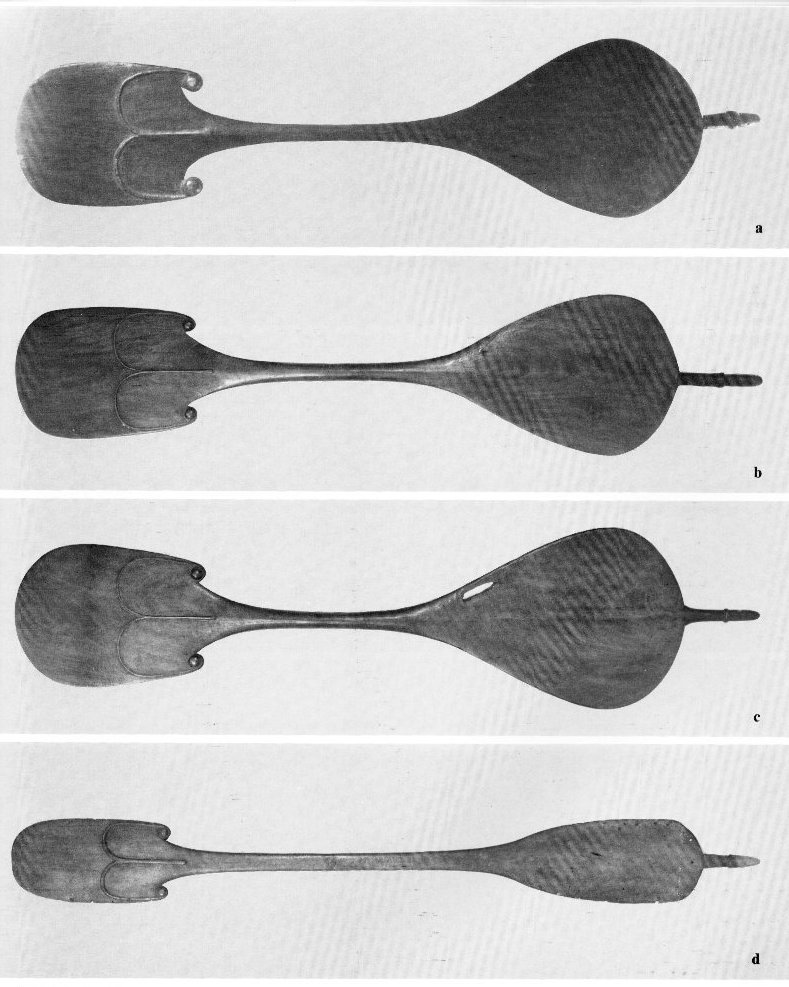

| "The ao and rapa

differ from each other mainly in size and in decoration, but are

otherwise closely related. Both were double-bladed paddles twirled

and shaken in the hand during ceremonial dances. The ao was

the larger of the two types, with a total length that could exceed 6

ft. (2 m.). One blade of the paddle, usually

pointing up during dances, has a conventionalized human face carved

and painted on each of its sides. The blade itself is carved flat as

on a functional paddle, with almost parallel edges and a rounded

distal end.

The nose is very long and extremely narrow, and

forks into two prominent eyebrows. This curved, Y-shaped combination

of nose and eyebrows is slightly raised in relief. The eyes are

carved and painted much larger than the mouth, which is either

reduced to a minimum or lacking. The ears, however, are invariably

present and carved in a conventionalized manner as two downward

projecting lobes with circular earplugs.

One very old and worm-eaten sample (Boston

64845) has fish vertebrae inserted as earplugs. The specimen,

collected by Agassiz' Albatross Expedition as late as 1904-5, has

doubtless been kept hidden in a cave. A large portion of the upper

blade, corresponding to the broad and tall forehead, is covered by

dense rows of vertically painted stripes that may indicate hair

although in some specimens they definitely assume the aspects of a

feather-crown of the type common in aboriginal Easter Island.

Some specimens have vertical tear marks painted as

parallel stripes running from the bases of the large eyes down

across the chin. This 'weeping-eye' motif is particularly pronounced

on the ancient ao symbols preserved as mural paintings on the

slabs in the ceremonial houses of Orongo (Ferdon, 1961, Figs.

65 b, f and Pl. 29 c; this vol., 183 a). Some faces on ao

paddles are painted with geometric fields suggesting tattoo.

Only one twin-faced blade of the ao is

painted; the rest of the paddle is left polished and plain. A slim

handle with an oval cross-section that becomes almost circular at

mid-length connects the painted blade with the other one which is

undecorated. It has the same outline except for the lack of

indentations carved below the earlobes of the decorated blade.

In some specimens the second blade is slightly

narrower and has a rounded rectanguloid outline. A fingerlike

projection with a ring-shaped band in relief around its midsection

is sometimes, but not always, carved at the center of the distal end

of this second blade. In some specimens the ring is replaced by a

steplike transition from a wider upper part to a narrower lower

part. This extension corresponds to the knob carved elsewhere on

some functional paddles and serves for pushing off or staking

operations." (Heyerdahl 3) |

The undecorated bottom paddle blade

presumably is female, while the top decorated one is male. Cocks have gaudy

colours, hens not.

Next page:

|

2.

Considering why there always are 3 vertical 'beams' in

hau tea - it must have a meaning - and based on the assumption

that it is sun beams which are illustrated, the natural conclusion will be that

the three 'beams' indicate

the division of the

day: "The

Hawaiian day was divided in three general parts, like that of the early Greeks

and Latins, - morning, noon, and afternoon - Kakahi-aka, breaking the

shadows, scil. of night; Awakea, for Ao-akea, the plain

full day; and Auina-la, the decline of the day.

The lapse of the night, however, was

noted by five stations, if I may say so, and four intervals of time, viz.: (1.)

Kihi, at 6 P.M., or about sunset; (2.) Pili, between sunset and

midnight; (3) Kau, indicating midnight; (4.) Pilipuka, between

midnight and surise, or about 3 A.M.; (5.) Kihipuka, corresponding to

sunrise, or about 6 A.M. ..." (Fornander)

Time consisted of night + day = 4 + 3 = 7. The Polynesians considered the

origin was in the darkest of night, with light arriving only later:

|

Night |

Kihi (sunset) |

|

| |

Pili |

| Kau

(midnight) |

|

| |

Pilipuka |

|

Kihipuka

(sunrise) |

|

|

Day |

Kakahi-aka |

morning |

|

Awakea |

noon |

|

Auina-la |

afternoon |

Fornander is not clear as to how the

night was structured in Hawaii, but 4 intervals of time there were. I have put midnight in a

special (black) box because it marks the 'death' of the old day (and the birth

of a new day). The division ('cut') of time at midnight makes it natural to have

a balance with 2 intervals before and 2 intervals after. There is no similar

'cut' at noon. Time begins anew (with a new cycle) at the darkest place.

Pilipuka is the first 'season' of the day and Pili the 7th. |

Hawaiian is harder to read than

other Polynesian dialects because they removed 't' from their alphabet. Kau

(midnight) could mean tau ('season') but also kau (swim), both

of which are reasonable. In the darkest of times there is no visible land

and you have to swim, and to mark the important border between one day and

the next a stone (tau) is used.

Words from 'foreign' Polynesian

dialects may have been preserved on Easter Island. Churchill's word list for

Mangareva, I have noticed, often is helpful, and the south - north travels

with Marquesas in the center, Hawaii in the north and Easter Island in the

south may have been more frequent than other trips across the sea, at least

during the later times when the Easter Polynesian dialects were being established

in the Pacific.

The 7th 'station', Pili, on

the other hand, is easy to transcribe into Rapanui:

| Piri

1. To join (vi, vt); to meet someone on the road;

piriga, meeting, gathering. 2. To choke: he-piri te

gao. 3. Ka-piri, ka piri, exclamation: 'So many!'

Ka-piri, kapiri te pipi, so many shellfish! Also used to

welcome visitors: ka-piri, ka-piri! 4. Ai-ka-piri ta'a

me'e ma'a, expression used to someone from whom one hopes to

receive some news, like saying 'let's hear what news you bring'.

5. Kai piri, kai piri, exclamation expressing: 'such a

thing had never happened to me before'. Kai piri, kai piri,

ia anirá i-piri-mai-ai te me'e rakerake, such a bad thing

had never happened to me before!

Piripiri, a slug found on the coast,

blackish, which secretes a sticky liquid.

Piriu, a tattoo made on

the back of the hand. Vanaga.

1. With, and. 2. A shock, blow. 3. To stick

close to, to apply oneself, starch; pipiri, to stick,

glue, gum; hakapiri, plaster, to solder; hakapipiri,

to glue, to gum, to coat, to fasten with a seal;

hakapipirihaga, glue. 4. To frequent, to join, to meet, to

interview, to contribute, to unite, to be associated,

neighboring; piri mai, to come, to assemble, a company,

in a body, two together, in mass, indistinctly; piri ohorua,

a couple; piri putuputu, to frequent; piri mai piri

atu, sodomy; piri iho, to be addicted to; pipiri,

to catch; hakapiri, to join together, aggregate, adjust,

apply, associate, enqualize, graft, vise, join, league, patch,

unite. Piria;

tagata piria, traitor. Piriaro

(piri 3 - aro), singlet, undershirt.

Pirihaga, to ally,

affinity, league. Piripou

(piri 3 - pou), trousers.

Piriukona, tattooing on

the hands. Churchill. |

To join, assemble (in mass), is one

of the meanings of piri. To stick together like the blackish slugs (piripiri)

on the coast (presumably the south coast) reminds us about Te Piringa

Aniva, the 7th kuhane station (if Maunga Hau Epa is

regarded as number 1) in the dark time when all the people gathered close

together, presumably to help nature in delivering the new 'fire' (first Sirius,

Te Pou, and later on sun). The structure is the same as that in the Hawaiian night.

It is a sluggish (slow and

irregular) time:

| Niva

Nivaniva,

madman, idiot. Vanaga.

Nivaniva,

absurd, stupidity, bungler, delirium, madness, to err, to wander

in mind, folly, foolish, heedless, frenzied, imbecile,

senseless, odd, inconsistent, simple, dupe, stupid, flighty (nevaneva);

nivaniva o te mata,

lethargy. Hakanivaniva,

queer, bewitched, stupefied, to tell lies. PS Ta.:

nivaniva,

neneva, foolish,

stupid, mad. Sa.: niniva,

giddy, dizzy. Churchill |

The people (aniva) is like

a mob, they can make the sun mobile again. Word play makes us understand.

In the beginning the gods were

like slugs, we should remember from the Haida:

|

Aanishaw

tangagyanggang, wansuuga. |

Hereabouts was all

saltwater, they say. |

|

Li

xitgwaangas, Xhuuya aa. |

He was flying all

around, the Raven was, |

|

Tigu

qqawgashlingaay gi lla quaangas. |

looking for land

that he could stand on. |

|

Qawdihaw gwaay

ghutgwa nang qaadla qqaayghudyas, |

After a time, at

the toe of the Islands, there was one rock awash. |

|

llagu qqawghaayghan

llagha lla xiidas. |

He flew there to

sit. |

|

|

|

Aa ttl sghaana

quiidas yasgagas ghiinuusis gangaang |

Like sea-cucumbers,

gods lay across it, |

|

llagu

gutgwii xhihldagahldiyaagas. |

putting their

mouths against it side by side. |

|

Ga sghaanagwaay

ghaaxas lla ttista qqaa sqqagilaangas, |

The newborn gods

were sleeping, out along the reef, |

|

ttl gwiixhang

xhahlgwii at wagwii aa. |

heads and tails in

all directions. |

|

Ghaadagas gyaanhaw

ising ghaalgagang, wansuuga ... |

It was light then,

and it turned to night, they say ... |

It must be a joke what comes at

the end, because obviously it was night then, and it turned to day. Light is

a word play on night.

The heads and tails (as if

flipping a coin, also a random event) of the

'cucumbers' were in all directions, describing the disorder before light

was 'turned on'.

The 'toe' on which Raven

'alighted' possibly indicates Hanga Te Pau - at least it is a kind of last station. Its

opposite should be at the other 'end' of the 'body', viz. at the 'snout':

| Ihu

1. Nose; ihu more, snub nose, snub-nosed

person. 2. Ihuihu cape, reef; ihuihu - many reefs,

dangerous for boats. 3. Ihu moko, to die out (a family of

which remains only one male without sons); koro hakamao te

mate o te mahigo, he-toe e-tahi tagata nó, ina aana hakaara,

koîa te me'e e-kî-nei: ku-moko-á te ihu o te mahigo, when

the members of family have died and there remains only one man

who has no offspring, we say: ku-moko-á te ihu o te mahigo.

To disappear (of a tradition, a custom), me'e ihu moko o te

tagata o te kaiga nei, he êi, the êi is a custom no

longer in use among the people of this island. 4. Eldest child;

first-born; term used alone or in conjunction with atariki.

Vanaga.

1. Nose, snout, cape T (iju G). Po

ihuihu, prow of a canoe. P Pau.: ihu, nose. Mgv.:

ihu, nose; mataihu, cape, promontory. Mq., Ta.:

ihu, nose, beak, bowsprit. Ihupagaha, ihupiro,

to rap on the nose, to snuffle. 2. Mgv.: One who dives deep.

Ta.: ihu, to dive. Churchill.

Sa.: isu, nose, snout, bill. Fu.,

Fakaafo, Aniwa, Manahiki: isu, the nose. Nuguria;

kaisu, id. Fotuna: eisu, id. Moiki: ishu, id.

To., Niuē, Uvea, Ma., Ta., Ha.,

Mq., Mgv., Pau., Rapanui, Tongareva, Nukuoro: ihu,

id. Rarotonga: putaiu,

id. Vaté: tus, id.

Viti: uthu, nose.

Rotumā: isu, id. ...

usu and

ngusu ... serve as transition

forms, usu pointing

to isu the nose in

Polynesia and ngusu

to ngutu the mouth,

which is very near, nearer yet when we bear in mind that

ngutu the mouth is snout as

well and that isu the

nose is snout too ...

Churchill 2. |

The name of the first Hawaiian

station, Pilipuka, ought to be pili-puka, and puka

maybe should be read as puta, cfr Rarotongan putaiu for

'nose', the 'nose' which has perforated (tiputa) the dark cloth,

I suppose:

| Tiputa

Pau.: To bore, to perforate. Ta.: tiputa,

to pierce. Mq.: tiputa, id. Ha.: kipuka, an

opening. Churchill |

The ti plant could

symbolize rebirth, we have learned from poporo.

Then we have rei puta, a

whale bone 'saviour of life':

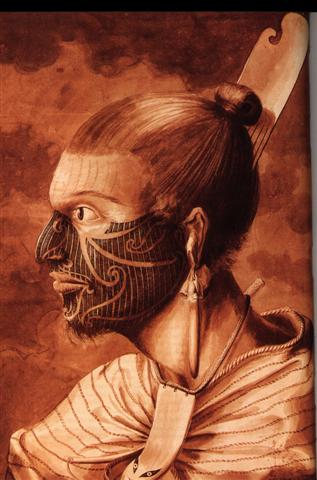

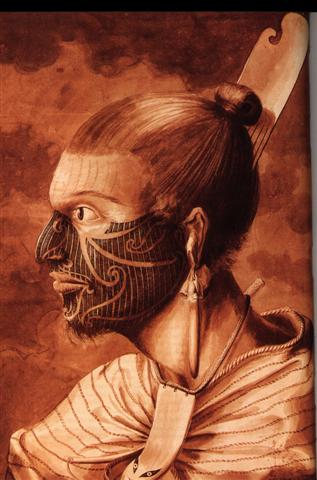

The picture is from

Starzecka and shows the tattooed son of a Maori chief.

| Rei

1. To tread, to trample on: rei kiraro ki te

va'e. 2. (Used figuratively) away with you! ka-rei kiraro

koe, e mageo ê, go away, you disgusting man. 3. To shed

tears: he rei i te mata vai. 4. Crescent-shaped breast

ornament, necklace; reimiro, wooden, crescent-shaped

breast ornament; rei matapuku, necklace made of coral or

of mother-of-pearl; rei pipipipi, necklace made of

shells; rei pureva, necklace made of stones. 5. Clavicle.

Îka reirei,

vanquished enemy, who is kicked (rei). Vanaga.

T. 1. Neck. 2. Figure-head.

Rei mua = Figure-head in

the bow. Rei muri =

Figure-head in the stern. Henry.

Mother of pearl;

rei kauaha, fin. Mgv.:

rei, whale's tooth.

Mq.: éi, id. This is

probably associable with the general Polynesian

rei, which means

the tooth of the cachalot, an object

held in such esteem that in Viti one tooth (tambua)

was the ransom of a man's life, the ransom of a soul on the

spirit path that led through the perils of

Na Kauvandra to the

last abode in Mbulotu.

The word is undoubtedly descriptive, generic as to some

character which Polynesian perception sees shared by whale ivory

and nacre. Rei kauaha

is not this rei; in

the Maori whakarei

designates the carved work at bow and stern of the canoe and

Tahiti has the same use but without particularizing the carving:

assuming a sense descriptive of something which projects in a

relatively thin and flat form from the main body, and this

describes these canoe ornaments, it will be seen that it might

be applied to the fins of fishes, which in these waters are

frequently ornamental in hue and shape. The latter sense is

confined to the Tongafiti migration.

Reirei, to trample down, to knead, to

pound. Churchill.

Pau.: Rei-hopehopega, nape. Churchill.

Mg. Reiga, Spirit leaping-place. Oral

Traditions. |

Now we are prepared to read about

the names of stars. Makemson:

"473. Pili-lua,

Two-friends-close-together; the Hawaiian form of Pipiri or Pipili,

whose myth is told throughout the Polynesian area. The Hawaiian pair of

stars was supposed to bring the opelu fish to local waters."

Maybe opelu

is o-pelu, and pelu = to fold, double over. If so, then there

will be - in a way - 'two friends close together'.

| Peu

1. Axe, adze, mattock;

peu pakoa,

an axe poorly helved. 2. Energy. Peupeu:

1. To groan. 2. To be affectionate, to grow tender;

peupeuhaga,

friendship. Mq.: pèèhu,

haápeéhu,

pekehu,

to make tender. 3. Pau.: peu,

habit, custom, manners. Ta.: peu,

custom, habit, usage. 4. Pau.: hakapeu,

to strut. Ta.: haapeu,

id. Churchill.

Sa.:

mapelu,

to bend, to stoop, to bow down, persons stooping with age,

housebeams sagging under weight. To.:

pelu,

bebelu,

to fold, to crease. Fu.: pelu,

peluki,

to fold. Uvea: pelu,

id., mapelu,

to bend, to bow. Ha.: pelu,

to double over, to bend, to fold. Rapanui:

peu,

axe, adze. Churchill 2. |

Te Peu

(significantly on the western coast close to the end of the kuhane

journey) is where Tuu Ko Ihu buried the head of Hotua Matua.

He was intending to be the 'nose' (ihu), the new boss.

Gemini, we can conclude, means the two friends close together

- one representing one side of the fold of time, the other the other side of

the fold. Spring equinox once was located in Gemimi.

"476. Pipili-ma, the Twins; a name for Lambda and

Upsilon Scorpii in Pukapuka.

477. Pipiri is the Maori name for the celebrated twins

who became stars. They are described as 'two stars of low rank', probably

referring to the degree of brightness, which rise shortly before the

Pleiades and herald the approach of the illustrious cluster and hence of a

new year Some

Maori tribes called the first month of the year Te Tahi-o-Pipiri, the

First of Pipiri, or by the abbreviated form Opipiri. Pipiri

was thus a synonym for winter, like Takurua, Sirius.

The Mangaians called the third month of the winter season

Pipiri. In Mangareva Pipiri was June, while in Easter Island it

stood for December.

Makemson can hardly have misunderstood, because the close (in

text and geography) Mangarevans had Pipiri properly located in June.

Maybe her source had misunderstood - on Easter Island Pipiri ought to

refer to 'December' rather than to December.

From the description it is evident that the Maori Pipiri

is the constellation Aries, which consists of two stars on the same diurnal

path as the Pleiades. In the Society Islands, Tuamotus and Pukapuka

Pipiri is identified as a double star in Scorpius, while in the Hawaiian

Islands Pililua is said to be Castor and Pollux.

Pipiri also appears in the form Oipiri.

According to a half-forgotten Maori myth, Oipiri and Whaka-ahu,

Castor, were the daughters of Po, Night, and Ao, Day. They

both became wives of Rehua. Oipiri was well versed in matters

pertaining to night and winter and she produced the snow. Whaka-ahu

was associated with summer and the world of light, marama heko-heko.

As night and day, cold and heat, summer and winter continually vie with one

another, so the attendants of Oipiri and Whaka-ahu are engaged

in an eternal conflict, but neither gains a permanent victory."

There is more in Makemson about pipiri, but this ought to be enough

for the moment. The main point is clear: Pipiri is an important

marker for a change of season.

|