|

TRANSLATIONS

At new year the ship of the sun starts its journey. We have seen that the Moriori fishermen on Chatham Islands - as if in imitation of the sun - launched a canoe on new years day: ... The triple division of the Marquesan year yields the segments August-November, December-March, and April-July ... ... The months were also personified by the Marquesans who claimed, as did the Moriori, that they were descendants of the Sky-father. Vatea, the Marquesan Sky-parent, became the father of the twelve months by three wives among whom they were evenly divided ... ... A curious diversion appears in the month list of the people of Porapora and Moorea in the Society Islands, which sheds light on the custom of the Moriori who sometimes placed 24 figures in the canoe which they dispatched seaward to the god Rongo on new years day. The names of the wives of the months are included, indicating that other Polynesians besides the Chatham Islanders personified the months ... Also on Easter Island similar ideas probably once ruled. A remnant is mentioned by Métraux under the rubric 'Recreation': ... on the first day of the year the natives dress in navy uniforms and performs exercises which imitate the maneuvers of ships' crews ... This increases the probability that the bottom part of Ab1-2 is meant do depict a canoe:

Metoro, instead of talking about ships, seems to have told about the sound of drums:

Probably the new year celebrations included the beating of drums. At 'dawn' bright colours as from the rainbow appear, the 'birds' wake up to try on their new gaudy habits and a lot of different noises will be heard when each bird thinks its own 'flute' is making a 'pretty sound'. The senses are filled to the brim. At new year the fireworks are needed not only for the eyes to watch, they have to denotate with the loudest possible sounds. We have our own 'recreations' of a new year. ... the succeeding Makahiki ceremony, following upon the putting away of the god, is called 'the net of Maoloha', and represents the gains in fertility accruing to the people from the victory over Lono. A large, loose-mesh net, filled with all kinds of food, is shaken at a priest's command. Fallen to earth, and to man's lot, the food is the augury of the coming year. The fertility of nature thus taken by humanity, a tribute-canoe of offerings to Lono is set adrift for Kahiki, homeland of the gods ... We note that 'the food is the augury of the coming year' and we should remember the ancient belief in a cosmic lottery at dawn. Dawn may come at different times, not just in the daily cycle but also in the yearly cycle of the sun, and then possibly twice because there are two 'years' in a year: ... der erste Monat des Jahres nach dem Schicksalsgemach (= Ubšugina) bezeichnet wird ... , der siebente aber d.i. der erste der zweiten Jahreshälfte nach dem im Ubšugina befindlichen Duazaga ... The decision makers up above must be induced to give us plenty of hua in the new period and we may now begin to appreciate the appearance of GD13 (rei) in Ab1-5. ... Up to the present time, fertility spells for fowls have played an important role. Especially effective were the so-called 'chicken skulls' (puoko moa) - that is, the skulls of dead chiefs, often marked by incisions, that were considered a source of mana. Their task is explained as follows: 'The skulls of the chiefs are for the chicken, so that thousands may be born' (te puoko ariki mo te moa, mo topa o te piere) ... As long as the source of mana is kept in the house, the hens are impregnated (he rei te moa i te uha), they lay eggs (he ne'ine'i te uha i te mamari), and the chicks are hatched (he topa te maanga) ... After a period of time, the beneficial skull has to be removed, because otherwise the hens become exhausted from laying eggs ... The canoe which is launched with tribute offerings to Lono (Rogo) has as its goal the homeland of the gods, Kahiki according to Hawaiian spelling, Tahiti in other Polynesian dialects. We must not think, though, that the destination is what we call Tahiti: "According to Maori Polynesian [meaning the descendants of those Northwest coast Indians who discovered Hawaii] tradition, the spring with the sacred life-giving water was reachable even by contemporary mortals provided they could manage the voyage eastwards across the sea, to the foreign land towards the sunrise, where it was still located. It was in a land foreign to the present island tribes, but it was 'in that ancient, well-remembered, and often-quoted home of the Polynesians ... situated in Kahiki-ku, ...' (Fornander 1878, Vol. I, p. 101). Kahiki, or Kahiki-ku (Sacred Kahiki), is, of all Polynesian allusions to the earliest Fatherland, the name most widely and commonly employed. Kahiki was the mainland home of the first godlike men who became the island discoverers, the home of the Tiki and Taranga family, and the place where true man was created. In Polynesia (as in Peru) the Flood must, however, have antedated the actual ancestral 'creation', for a Polynesian legend states that it was not until after that primary man-destroying catastrophe that the survivors in their vessel first 'landed and dwelt in Kahiki-honua-kele, a large and extensive country.' (Ibid., p. 91)1 1 We recall as a peculiar aspect of both Peruvian and Polynesian mythology that some people were said to have lived in obscurity and darkness even before the creation of sunlight and the proper ancestral tribes. From that initial arrival after the flood - that is through the scene of human creation and all successive events until Maui-Tiki-Tiki and his contemporaries settled the islands in the Polyensian Ocean - did the forefathers of the islanders reside on the great mainland of Kahiki, which was said to border directly on the ocean. (Ibid., p. 101, etc.) We have seen ... that in New Zealand and several islands of Polynesia proper - but not in Hawaii - the natives possess distinct traditions to the effect that the secondary invasion of the islands came at the beginning of the present millenium by way of a group of islands termed Hawaiki, and located in the north. Thus began the actual Maori-Polynesian period. But before this event, and associated with the gods and god-like men of the earliest legendary island era, we hear the numerous references to the glorious kingdom of Kahiki. Percy Smith (1910 a, p. 216) writes: 'I judge from Fornander that the Hawaiians have no tradition of any Hawaiki in the Pacific, but in their word Ka-hiki we may probably trace the name Fiji as well as Ta-hiti.' In spite of this relationship in name, none of these three places are geographically identifiable one with the other. From the numerous references to Kahiki-ku it is clear that it is no circumnavigable island, but a sub-division of a vast continent, with ocean only on one side. It is referred to in other Polynesian dialects also as Tawhiti and Tefiti. We may therefore well assume that Fiji (properly: Viti), as well as Tahiti in the Society Group, have both taken their names from this same mythical source, the sacred Kahiki-ku of songs and traditions. In analysing the etymology of this early mythical name, Percy Smith (Ibid., p. 111) came to the following interesting conclusion: 'Ta is a prefix of a causative nature, Whiti, or Hiti, is to rise up, as the sun, and also means the east.' In fact, all through Polynesia, from Easter Island to Fiji, from Hawaii to New Zealand, we meet the word hiti, viti, hiki, whiti, fiti, and iti, always meaning 'sunrise', 'east', or 'towards east'. Gill (1876, p. 17), and with him also Steinen (1933, p. 19), reached the very same conclusion as Smith on the etymology of this ancient place-name, giving it as a composite of a causative and the Polynesian word for 'east'.1 1 Gill (loc. cit.), who received first hand information among the aborigines of the Hervey Islands concerning the etymology of the name Tahiti, wrote: It is said that the 'spirit' name of Tahiti is 'Iti', i.e. 'iti nga' = sun-rising. Tahiti simply means 'east', or 'sun-rising', from hiti (our iti) to 'rise': ta being causative. The island was known in the Hervey Group by the name Iti or 'east': it is only of late years the full name Tahiti has become familiar ..." (Heyerdahl 6) The Flood, I believe, is a description of how sun disappears in autumn - the great fire is extinguished and the cause surely must be vast amounts of water. In the solar calendar of the year the period between 260 to 364 nights probably represents the 'Flood'. The eternal sun is reborn again like a little child in the midst of the dark season, at winter solstice, and his power is not yet very great. Therefore darkness (moon) still rules. The event of His birth must anyhow be celebrated and it is a kind of dawn. To send a ship with light is a gesture of welcome and of sympathetic magic - Tahiti (Oh, rise!), or even better, Mata Tahiti (Oh, rise Great Eye!) - in a shorter form with the Hawaiians, Makahiki:

... The Loy Krathong-feast ... is a feast for Thai people when they celebrate and thank the Water Goddess. People go down to the sea and put afloat a little boat made of banana leaves. Inside there is a little lighted candle ... Let us continue from Heyerdahl 6: ... there is a graphic distinction between Polynesian information pertaining to immaterial spirits and that relating to seafaring ancestors. Those of the Polynesians who let their departed spirits follow in the trail of the setting sun were confident that they would enter the gateway at Haehae in the east next morning, and thus find the way to paradise with the sun as guide.

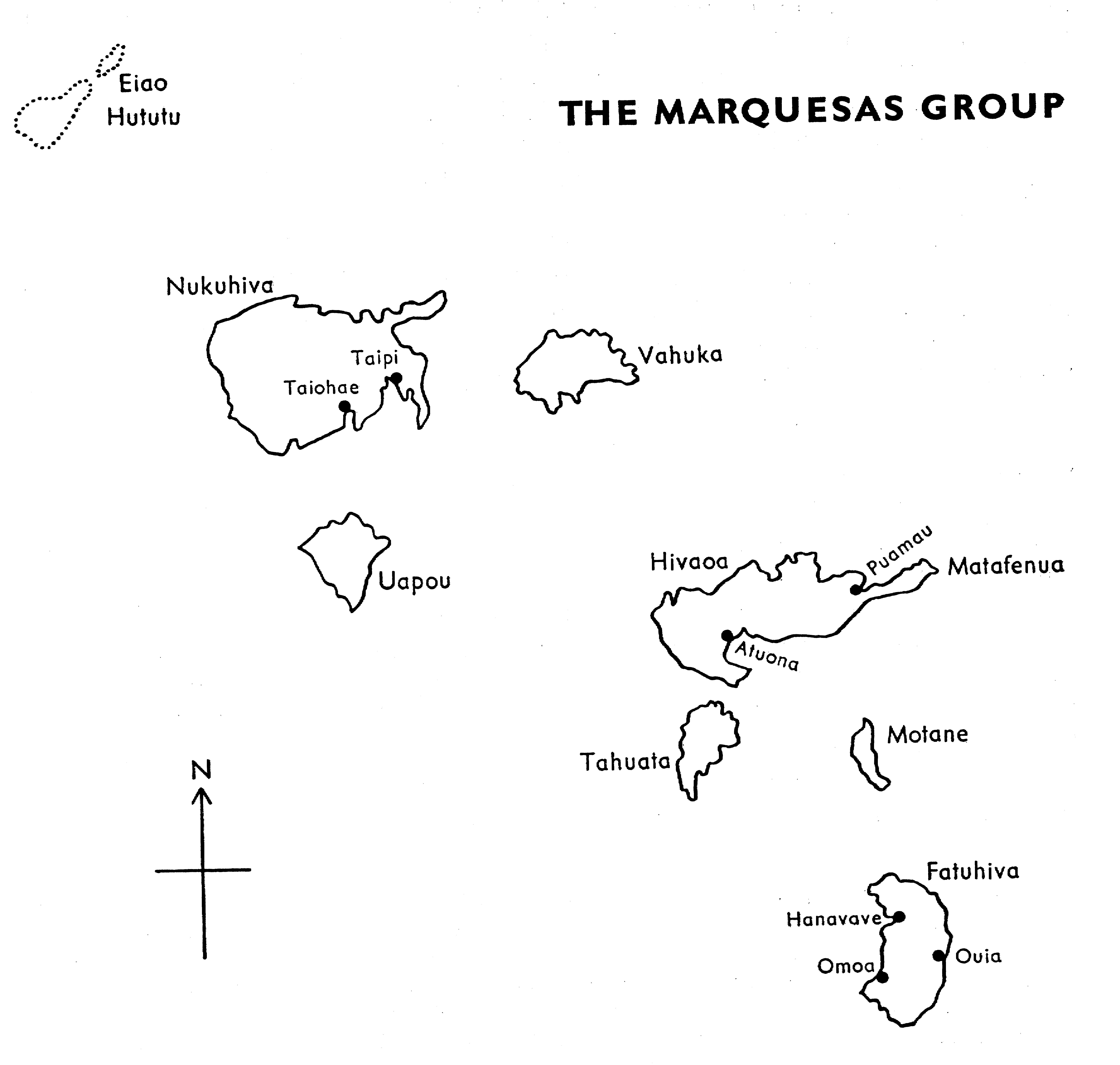

But Kahiki itself was only secondarily a tempting home for returning spirits; it was above all a real land, the designation of a distant mountainous mainland bordering on the Polynesian ocean, whence mankind migrated to the present occupied groups. There are even some few legends which claim that certain early heroes made a return visit to Kahiki ... their steering orders were then to direct their bows 'to the rising sun'. A distinct tradition to this effect is also recorded from the Marquesas, in an account of a visit to Tefiti. (Fiti is the Marquesan pronounciation of hiki, 'east', and te is their definite article.) In his Marquesan Legends, Handy (1930, a p. 131) narrates that a party of 'men, women and children' embarked in a double canoe of extraordinary size, which was named Kaahua. Setting out on their long expedition from the Marquesas group 'they sailed east, and finally reached a land called Tefiti. Some of the explorers remained at this land, while others returned to Puamau on 'Kaahua' ... A map included in Heyerdahl 6 shows that Puamau is located on Hivaoa:

As there is no land short of Pacific South America to the eastwards of the Marquesas group, Handy was much puzzled by this itinerary for a voyage to Tefiti, but, he stresses, 'my informant insisted that this land was toward the rising sun (i te tihena oumati).' Steinen (1933, 0. 10) heard the Marquesans referring to the same eastern land as Fitinui, 'Great Fiti', or the 'Great East'. They stressed that this Great Fiti was not in the direction of the other Pacific islands, but across the ocean to the east of their own group, 'beyond the eastern cape of Matafenua.' ... Steinen (Ibid.) also points to the curious fact that the term fiti, which on the other islands means 'sunrise', in the Marquesas has a double significance, namely 'to go towards the east', and also 'to go inland from the coast' or 'uphill from seashore'. He tries to explain this as having originated from the time of navigation,when 'to go towards the east' would be to ascend against the trade wind, a regular uphill movement. This is a very plausible explanation, yet it is not impossible that the double significance of the word has survived from a time when the Marquesans' ancestors lived in that great land to 'the East', i.e. Pacific South America, where 'to go east' and 'to go inland' would actually be one and the same thing.1 1 It is true that the Polynesians considered an eastward voyage by water-craft as an uphill voyage, and a westward voyage as one going downhill over the ocean surface. Henry (1928, p. 436) states that in regular boasting competitions the Raiateans would try to the best of their ability to belittle Tahiti. "To this retort the Tahitians would reply. 'How can Tahiti be underrated by Raiatea? The sun rises over Tahiti, and sets over Raiatea; the moon ascends over Tahiti and sets over there ... You are indeed below in the west, and we are above in the east here. When Raiateans come to Tahiti, they say they are sailing up, and it is really up. But when they return to Raiatea, they say they are sailing down, and Raiatea is really down from Tahiti.' And so the dispute ended." Fornander (1878, Vol I, p.18) also recorded: "In many of the Polynesian groups the expressios 'up' and 'down' (Haw., iluna or manae and ilalo) are used with reference to the prevailing trade-winds. One is said to 'go up' when travelling against the wind, and to 'go down' when sailing before it." The feeling that the Pacific Ocean 'slopes down' from east to west was most vividly experienced by the members of the Kon-Tiki raft expedition. I suppose the little canoe with a lighted candle will reach the eastern abode of the sun by drifting downhill - moved westwards by winds and currents - but it surely will take some time. Poike is a good symbol for 'noon', it lies 'uphill' in the east and poike in the Maori language means 'place aloft' according to Barthel 2. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||