|

TRANSLATIONS

The canoe - I still have it in my mind - is

a natural symbol for balance:

|

...

Amalivaca

broke his daughters' legs in

order to prevent them travelling

hither and thither and to force

them to remain in one place, so

that their procreative powers,

which had no doubt been put to

wrong uses during their

adventurous wanderings, should

henceforth be confined to

increasing the Tamanac

population. Conversely,

Mayowoca bestows legs on a

primeval and, of necessity,

sedentary couple, so that they

can both move about freely and

procreate.

In M415,

the sun and the moon are fixed

or, to be more exact, their

joint representation in the form

of rock carvings provides a

definitive gauge of the moderate

distance separating them and the

relative proximity uniting them.

But, since the rock is

motionless, the river below

should - supposing creation were

perfect - flow both ways, thus

equalizing the journeys upstream

and downstream. Anyone who has

travelled in a canoe knows that

a distance that can be covered

in a few hours when the journey

is downstream may require

several days if the direction is

reversed. The river flowing two

ways corresponds then, in

spatial terms, to the search, in

temporal terms, for a correct

balance between the respective

durations of day and night ...

such a balance should also be

obtainable through the

appropriate distance between the

moon and the sun being measured

out in the form of rock carvings

... |

Lévi-Strauss does not here mention the

feeling you get when entering a canoe - how

you have to be careful not to disturb the

balance. Yet in a canoe you feel safe in

high waves. A canoe is not characterized by

spatial or temporal distances, it is

characterized by stability (like the sun on

his path). Therefore, it

would not have been bad if I had said

something about the canoe as a security

symbol in my summary of Rei:

|

The rei miro glyphs were

used by the rongorongo

men to mark cardinal points,

i.e. points where the direction

of the journey of the sun canoe

across the blue sea of the sky

had to be adjusted.

The orientation of the canoe as

seen in the glyphs is therefore

'standing on its front end'. It

has stopped for a moment and a

new straight course will soon

begin.

Whereas the sun is steady and

always the same the moon is the

incarnation of change. Therefore

the rei miro glyphs have

'appendices' in form of

'sickles' below the hull, a sign

to indicate the moon. Rei

miro glyphs always appear

when change is due, never at

other times.

The calendars for the year had

the solstices and equinoxes

located at points which did not

coincide with the points where

the major calendar periods

changed. In that respect their

view corresponds with our view:

New year arrives, for example,

later than winter solstice and

spring equinox before the 1st of

April. |

Rei glyphs always appear when change

is due, because they give security. (I

notice how I wrote rei miro glyphs

instead of Rei glyphs and have to

change that at once.)

Next page in the glyph dictionary:

|

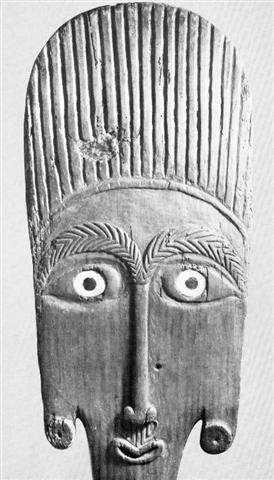

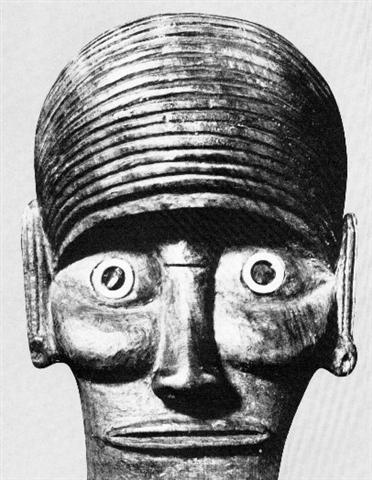

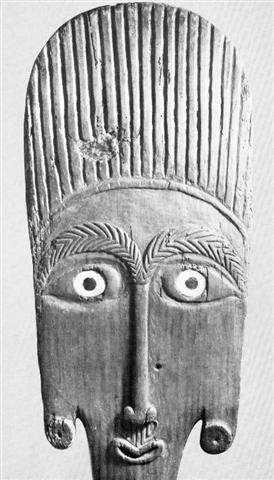

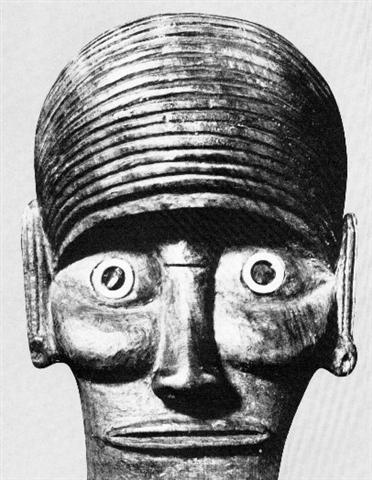

4. The

long nose in the ao face has the appearance of a

tree:

This tree is located at summer solstice, and the 'tree' in the

ua face should be the same tree at winter solstice. It is (in a

way) the tree which grew from the heart of Ulu:

... His wife sang a

dirge of lament, but did precisely as she was told, and in the

morning she found her house surrounded by a perfect thicket of

vegetation. 'Before the door,' we are told in Thomas Thrum's

rendition of the legend, 'on the very spot where she had buried her

husband's heart, there grew a stately tree covered over with broad,

green leaves dripping with dew and shining in the early sunlight,

while on the grass lay the ripe, round fruit, where it had fallen

from the branches above. And this tree she called Ulu

(breadfruit) in honor of her husband ...

It is also (in a way) the tree in which the head of One

Hunaphu was placed:

... And they were

sacrificed and buried. They were buried at the Place of Ball Game

Sacrifice, as it is called. The head of One Hunaphu was

cut off; only his body was buried with his younger brother. 'Put his

head in the fork of the tree that stands by the road', said One

and Seven Death. And when his head was put in the fork of the

tree, the tree bore fruit. It would not have had any fruit, had not

the head of One Hunaphu been put in the fork of the tree.

This is the calabash, as we call it today, or 'the skull of One

Hunaphu', as it is said. And then One and Seven Death

were amazed at the fruit of the tree. The fruit grows out

everywhere, and it isn't clear where the head of One Hunaphu

is; now it looks just the way the calabashes look. All the

Xibalbans see this, when they come to look

...

It is the coconut tree, and all sorts of fruitful mythic trees. They

represent the vertical 'cosmic tree' which keeps the sky dome up.

Probably it is seen as the middle of hua poporo.

We say south 'pole' and north 'pole' and mean this 'tree'. On

Easter Island, when sun stands low, the 'face' is compressed like

the face on the ua staff.

In the beginning sky was lying directly on the surface of the

earth and it was totally black in between. Tane (the god of

trees) managed to raise the sky and let in the light:

... Sky (rangi)

and Earth (papa) lay in primal embrace, and in the cramped,

dark space between them procreated and gave birth to the gods such

as Tane, Rongo and Tu. Just as children fought

sleep in the stifling darkness of a hare paenga, the gods

grew restless between their parents and longed for light and

air. The herculean achievement of forcing Sky to separate from Earth

was variously performed by Tane in New Zealand and the

Society Islands, by Tonofiti in the Marquesas and by Ru

(Tu) in Cook Islands. After the sky was raised high above the

earth, props or poles were erected between them and light entered,

dispelling the darkness and bringing renewed life ...

Ure Honu (who had found the skull of the sun king - helped by a rat, the

kuhane of Hotu Matua) later lost it

and searched inside the 'house' of king

Tuu Ko Ihu. The house is a symbol for the dome of the sky

and the roof needs props (tree stems), otherwise it will be

completely dark inside. |

|

"...

Ure Honu

was amazed and said, 'How beautiful you are! In the head of the new

bananas is a skull, painted with yellow root and with a strip of

barkcloth around it.'

Ure Honu

stayed for a while, (then) he went away and covered the roof of his

house in Vai Matā. It was a new house. He took the very large

skull, which he had found at the head of the banana plantation, and

hung it up in the new house. He tied it up in the framework of the

roof (hahanga) and left it hanging there.

Ure

sat out and caught eels, lobsters, and morays. He procured a great

number (? he ika) of chickens, yams, and bananas and piled

them up (hakatakataka) for the banquet to celebrate the new

house. He sent a message to King Tuu Ko Ihu to come to the

banquet for the new house in Vai Matā. A foster child (maanga

hangai) of Ure Honu was the escort (hokorua) of

the king at the banquet and brought the food for the king, who was

in the house. The men too came in groups and ate outside. When

Tuu Ko Ihu had finished his dinner, he rested. At that time he

saw the skull hanging above, and the king was very much amazed.

Tuu Ko Ihu knew that it was the skull of King Hotu A Matua,

and he wept. This is how he lamented: 'Here are the teeth that ate

the turtles and pigs (? kekepu) of Hiva, of the

homeland!'

After Tuu Ko Ihu had reached up with his hands, he cut off

the skull and put it into his basket. Out (went) the king, Tuu Ko

Ihu, and ran to Ahu Tepeu. He had the skull with him.

King Tuu Ko Ihu dug a hole, made it very deep, and let the

skull slide into it. Then he cushioned the hole with grass and put

barkcloth on top of it, covered it with a flat slab of stone (keho),

and covered (everything) with soil. Finally, he put a very big stone

on top of it, in the opening of the door, outside the house.

Ure Honu looked around for his skull. It was no longer in the

house. When he questioned those who knew, the foster child of Ure

Honu said, 'On the day on which the banquet for the new house

was held, Tuu Ko Ihu saw the skull. He was very much moved

and wept, 'Here are the teeth that ate the turtles and the pigs (?

kekepu) of Hiva, of the homeland!' When the foster

child of Ure Honu had spoken, Ure Honu grew angry. He

secretly called his people, a great number of men, to conduct a raid

(he uma te taua).

Ure set out and arrived in front of the house of Tuu Ko Ihu.

Ure said to the king, 'I (come) to you for my very large and

very beautiful skull, which you took away on the day when the

banquet for the new house was held. Where is the skull now?'

(whereupon) Tuu Ko Ihu replied, 'I don't know.'

When Tuu Ko Ihu came out and sat on the stone underneath

which he had buried the skull, Ure Honu shot into the house

like a lizard. He lifted up the one side of the house. Then Ure

Honu let it fall down again; he had found nothing. Ure Honu

called, 'Dig up the ground and continue to search!' The search

went on. They dug up the ground, and came to where the king was. The

king (was still) sitting on the stone. They lifted the king off to

the side and let him fall. They lifted up the stone, and the skull

looked (at them) from below. They took it, and a great clamour began

because the skull had been found. Ure Honu went around and

was very satisfied. He took it and left with his people. Ure Honu

knew that it was the skull of the king (puoko ariki)." (Manuscript

E according to Barthel 2) |

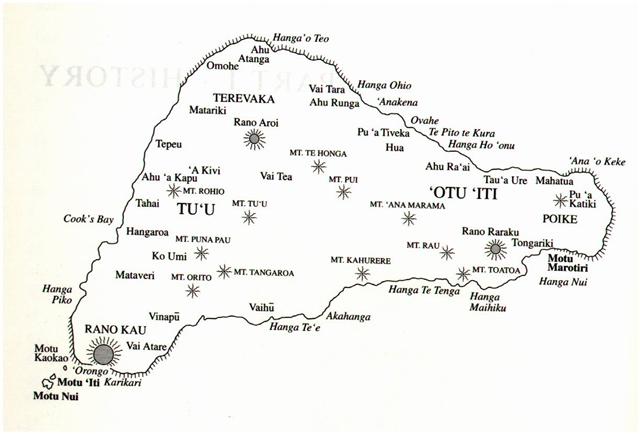

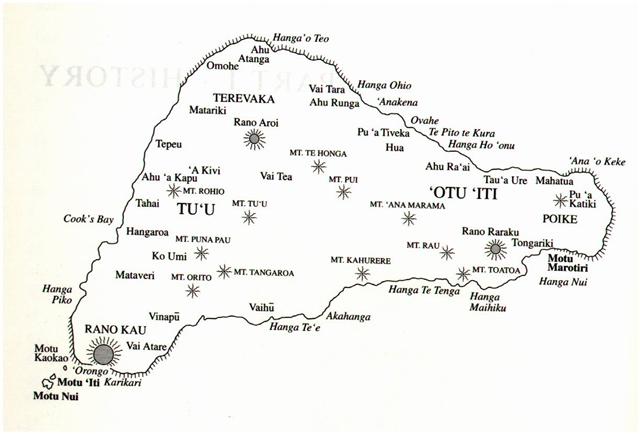

Tuu Ko Ihu went to Ahu Tepeu,

a name we recognize. It is located in the

domain of Tu'u, in the west:

I add peu to my Polynesian

dictionary, and cannot but notice the

meaning 'to fold, to crease' (just as in

winter the 'face' becomes wrinkled like the

forehead of ua):

| Peu

1. Axe, adze, mattock;

peu pakoa,

an axe poorly helved. 2. Energy. Peupeu:

1. To groan. 2. To be affectionate, to grow tender;

peupeuhaga,

friendship. Mq.: pèèhu,

haápeéhu,

pekehu,

to make tender. 3. Pau.: peu,

habit, custom, manners. Ta.: peu,

custom, habit, usage. 4. Pau.: hakapeu,

to strut. Ta.: haapeu,

id. Churchill.

Sa.:

mapelu, to bend, to

stoop, to bow down, persons stooping with age, housebeams sagging under

weight. To.: pelu,

bebelu,

to fold, to crease. Fu.: pelu,

peluki,

to fold. Uvea: pelu,

id., mapelu,

to bend, to bow. Ha.: pelu,

to double over, to bend, to fold. Rapanui: peu,

axe, adze. Churchill 2. |

It is because of the sagging housebeams. The

old king (Tuu Ko Ihu) is stooping

with age, folding over, and will soon fall

on his face.

('They lifted the king off to the side and

let him fall.')

Why an axe? Probably because

the old 'tree' must be felled.

From this viewpoint ua glyphs in the

rongorongo texts should be studied.

|