|

TRANSLATIONS

The world of rottenness is the world of the mortals. The Raw and the Cooked: "... With reference to the contrast between rock and decay, and its symbolic relation with the duration of human life, it may be noted that the Caingang of southern Brazil, at the end of the funeral of one of their people, rub their bodies with sand and stones, because these things do not rot. 'I am going to be like stones that never die', they say'. 'I am going to grow old like stones ..." Stone is tau in Rapanui, as eg in Tautoru (The Belt of Orion) and Tauono (The Pleiades). Stars are reliable and permanently there (immortal). But tau is also 'season' (or rather the 'produce of the season'). The seasons are also reassuringly reliable. Cooking implies mortality, The Raw and the Cooked: "... comparison between the Apinaye and Caraja versions, which tell the story of how men lost immortality, provides an additional interest, in that it establishes a clear link between this theme and that of the origin of cooking. In order to light the fire, dead wood has to be collected, so a positive virtue has to be attributed to it, although it represents absence of life. In this sense, to cook is to 'hear the call of rotten wood'. But the matter is more complicated than that: civilized existence requires not only fire but also cultivated plants that can be cooked on the fire. Now the natives of central Brazil practice the 'slash and burn' technique of clearing the ground. When they cannot fell the forest trees with their stone axes, they have recourse to fire, which they keep burning for several days at the base of the trunks until the living wood is slowly burned away and yields to their primitive tools. This preculinary 'cooking' of the living tree poses a logical and philosophical problem, as is shown by the permanent taboo agains felling 'living' trees for firewood. In the beginning, so the Mundurucu tell us, there was no wood that could be used for fires, neither dry wood nor rotten wood: there was only living wood ... Therefore only dead wood was legitimate fuel. To violate this regulation was tantamount to an act of cannibalism against the vegetable kingdom." In the beginning there was no fire domesticated. Domestic fires need dry wood, therefore trees must die. Fetching the 'fire' from the gods in the sky to enable 'cooking' implies that trees (and men) must die for the necessary 'circulation': '... To draw up and then return what one had drawn - that is the life of the world' ... '... In many lands, at the time of marriage, the kindling of the hearth in the new home is a crucial rite, and the domestic cult comes to focus in the preservation of its flame. Perpetual flames and votive lights are known practically everywhere in the developed religious cults. The vestal fire of Rome, with its attendant priestesses, was neither for cooking nor for the provision of heat. And we have already learned of the holy fire made and extinguished at the times of the installation and murder of the god-king ...' Flames (sky) and stones (earth) and water (underworld) are immortal, they are not being 'cooked'. Instead they are the fundamental ingredients for life and death. Once again, Thursday:

Two heads on one body (GD65) illustrates the conjunction of 'sky' (man, fire) and 'earth' (woman, water). The haati kava (GD34) glyphs tell us that new 'fire' arrives from the 'sky'. The 'cooking' means 'eating' (GD52, kai), and presumably some 'kava' ceremony is also alluded to. Possibly the GD52 glyphs in H follow the pattern 3 + 1, though the 3-group glyphs are not exacly alike (e.g. different hands). The 1st glyph has the Y-shape as hand and is therefore immediately recognized as different from the other 3. The glyph is also turned around looking backwards, and it certainly must mean something else than the other 3. Maybe the 1st glyph is the 'old king' ('rotten' and passé). We remember the looks of the 'odd' GD11:

'In this piece of ceramics we find the 'staircase' in both white

and black.

The earth is receiving light, heat and water (wavy lines) from the sun (6 double suns at top). Our world in sunlight is white and the black world below (as in a mirror) has also 6 double suns.' "The sun at noon is the sun declining; the creature born is the creature dying." (Hui Shih, ca 3rd century BC, according to Needham II.) From Adam's rib Eve was created. Churchill pointed out that kavakava (= rib) is related to vakavaka:

The canoe (vaka) is female, cfr Vakai. But she carries a male child (fire) inside. rib ... any of the curved bones articulated to the spine ... wife, woman (in allusion to Gen. ii 21) ... OHG. hirni|reba brain-pan, cranium, Gr. orophé roof, eréphein roof cover. (English Etymology) ribald ... rascal, licentious person ... OHG. hriba ... whore, MHG. rīben be on heat, copulate ... (English Etymology) ribband ... (naut.) any of the long flexible timbers fastened to the ribs of a ship ... (English Etymology) ribbon ... narrow woven band of fine material... (English Etymology) '... Sacred product of the people's agriculture, the installation kava is brought forth in Lau by a representative of the native owners (mataqali Taqalevu), who proceeds to separate the main root in no ordinary way but by the violent thrusts of a sharp implement (probably, in the old time, a spear). Thus killed, the root (child of the land) is then passed to young men (warriors) of royal descent who, under the direction of a priest of the land, prepare and serve the ruler's cup ... the tuu yaqona or cupbearer on this occasion should be a vasu i taukei e loma ni koro, 'sister´s son of the native owners in the center of the village'... Traditionally, remark, the kava root was chewed to make the infusion: The sacrificed child of the people is cannibalized by the young chiefs. The water of the kava, however, has a different symbolic provenance. The classic Cakaudrove kava chant, performed at the Lau installation rites, refers to it as sacred rain water from the heavens... This male and chiefly water (semen) in the womb of a kava bowl whose feet are called 'breasts' (sucu),

(pictures from Lindqvist showing very old Chinese cooking vessels) and from the front of which, tied to the upper part of an inverted triangle, a sacred cord stretches out toward the chief ... The cord is decorated with small white cowries, not only a sign of chieftainship but by name, buli leka, a continuation of the metaphor of birth - buli, 'to form', refers in Fijian procreation theory to the conceptual acception of the male in the body of the woman. The sacrificed child of the people will thus give birth to the chief. But only after the chief, ferocious outside cannibal who consumes the cannibalized victim, has himself been sacrificed by it. For when the ruler drinks the sacred offering, he is in the state of intoxication Fijians call 'dead from' (mateni) or 'dead from kava' (mate ni yaqona), to recover from which is explicitly 'to live' (bula). This accounts for the second cup the chief is alone accorded, the cup of fresh water. The god is immediately revived, brought again to life - in a transformed state ...' The sacred fire lit at the time ('Thursday') of the installation of the new great chief may be universal, and therefore may also describe how the early Polynesians once came over the sea in their canoes to Hawaii, taking charge over the new land and its people, possibly at the time of volcanic eruptions: "The great 'wandering chief' who is said to have discovered the Hawaiian islands is alluded to as Hawaii-loa, or 'Hawaii-the-great', (but his name is also repeatedly given as Ke Kowa-o-Hawaii, or 'The Straits of Hawaii'. (Fornander 1878, Vol. I, p. 23, 25.) The island Hawaii was named after this mythical wanderer, and hence the name must be a very ancient one brought to Hawaii by its early settlers. Fornander himself was sufficiently familiar with the Polynesian predilection for allegories and symbolic names to realize that 'the Straits of Hawaii' was merely a poetical device, a descriptive mythical name personified in the local discoverer, and he proceeded to trace its possible origin. He and others have shown that Hawaii, alias Hawaiki, is a composite name, consisting of a root with the suffix ii, alias iki. Iki is the original form, and ii the result of a later dropping of the letter k. Philologists have suggested two possible meanings for this suffix; on one hand 'small' or 'little'; on the other 'furious' or 'raging' as referring to a volcano in eruption. The improbability of the first of these meanings is apparent from the old Polynesian use of words like Hawaii-loa and Hawaii-nui, which would produce the senseless suffix 'Little-Great'. And, as shown by Fornander (Ibid., p. 6), a Marquesan tradition shows plainly that ii refers to a volcano: '... in a chant of that people, referring to the wanderings of their forefathers, and giving a description of that special Hawaii on which they once dwelt, it is mentioned as Tai mamao, uta oa tu te Ii - a distant sea (or far off region), away inland stands the volcano (the furious, the raging).' According to Henry (1928, p. 115), also Tahitian folklore often spoke of Hawaii Island as Havai'i-a, or 'Burning Havai'i', due to its volcano which was formerly always brightly burning. Thereupon Fornander and others with him removed the epithet ii or iki, and looked to the west for a place-name equivalent to Hawa (of Hawaii), Sava (of Savaii), or Hapa (of Hapaii). Suspicion naturally fell on Java, and the name of this island was by many considered the clue to the 'whence' of the Maori-Polynesian ancestors. After jumping a good 6,000 miles from Hawii to Java, he then took a further leap of 5,000 miles back to Zaba, the early seat of Cushite empire in Arabia, as the ancestral starting point. However, finding nowhere any 'Strait' with a name equivalent to Hawa or Hawaii, Fornander (p. 25) simply suggests that the allegoric reference to the Hawaiian discoverer as 'the Straits of Hawaii' must refer to the Hawaiian memory of a now lost name for the Straits of Sunda between Java and Sumatra. Here the question was left. Taking up Fornander's original clue, the present author suspected that Hawai (or Savai, Hapai) might have been the old root from which the name sprang, rather than Hawa. As stated earlier, Whatonga's legendary canoe in Hawaiki was named Te Hawai, not Te Hawa nor Te Hawaiki; and in Hawaii ancient place-names like Kaha-hawai, Puna-hawai, etc. are found. Even more suggestive is the fact that, as stated, the epithet ii or iki refers to a raging, active volcano, of which there are none in Polynesia outside the Hawaiian and Samoan groups and New Zealand. There are two in Hawaii in the Hawaiian Group, and another in Savaii, but there is none in Hapai in the Tonga Islands. Therefore, Hawaii and Savaii, but not Hapai, have been given the suffix ii, denoting a volcano. Yet, even without the ii, this Tonga island is known as Hapai and not as Hapa, quite in keeping with the name of Whatonga's canoe Te Hawai from Hawaiki. The reduction of a consonant, changing Hawaiki to Hawai'i and Hapaiki to Hapai'i, is a well known process in Polynesian speech, but no Polynesian dialect would abbreviate Hapai'i to Hapai. On the other hand, Hapai may very well be the root of Hapai-iki, and the canoe Te Hawai may be the root of Te Hawai-iki. Recalling at the same time the marked softening tendency throughout Polynesian speech, the p in Hapai is obviously an older form than w in Hawai. On these premises I resumed the search outside Polynesia for Hapai, or even for the more guttural Hakai. My own little table (from Krupa) over Polynesian spelling conventions does not list any 'p' (as in Hapa) corresponding to 'w' (or 'v'). Neither is 'k' anywhere to be found as an equivalent. Though Hawaiian 'k' corresponds to 't' in most other areas of Polynesia (which sounds more harsh than 't' to my ears), for example Kane instead of Tane. Earlier I wrote: A systematic analysis of what words Metoro used at glyphs with uplifted inwards oriented hands results in my idea that the concept is locality, e.g. noho = to sit, to stay, to live somewhere. Maybe there is a kind of logic, with one hand inwards bent meaning kai (= to eat, drink, talk etc), and two hands inwards bent - one from each direction - a place for kai, i.e. kaiga. Then this image could be used for locality as such (-ga). This idea of mine fits in nicely with what Barthel writes about this type of glyph:

(Though I have not yet been able to localize any such glyphs in the texts.) "Für Tu, der erstgeborenen Sohn des Gottes Tangaroa, wird als Herrschaftsregion 'Apai' oder 'Hapai' genannt, einer der fünf Bereiche des Jenseits.1) 1) Hiroa 1938, 421, 422, 424, 504. Ausführlich 470: 'Hapai was a good Po located in the sky... Tu and his descendants dwelt there... Hapai was a place of feasts and enjoyment. The entrance was through the mouth of Ruanuku... Ataatakirei, the home of Tu, was located in Hapai. Tagaroa visited his son Tu in Hapai after he left his wife Haumea... - Zur lokalisierung im Himmel vgl. das Auftreten von 'rangi' in Tafeltexten für den einäugigen Gott. - Zu 'ataatakirei' vgl. 'Apai'-Gesang (tangaroa te mare kura hapai). Tatsächlich scheint nun die besondere Armhaltung der Zeichens 501 gerade den Wert 'hãpai' zu besitzen und so eine ergänzende Ortsangabe für den Gott Tu darzustellen." (Barthel) Reading now in my wordlists I easily can grasp why Barthel thought about his 501 as equivalent to hapai:

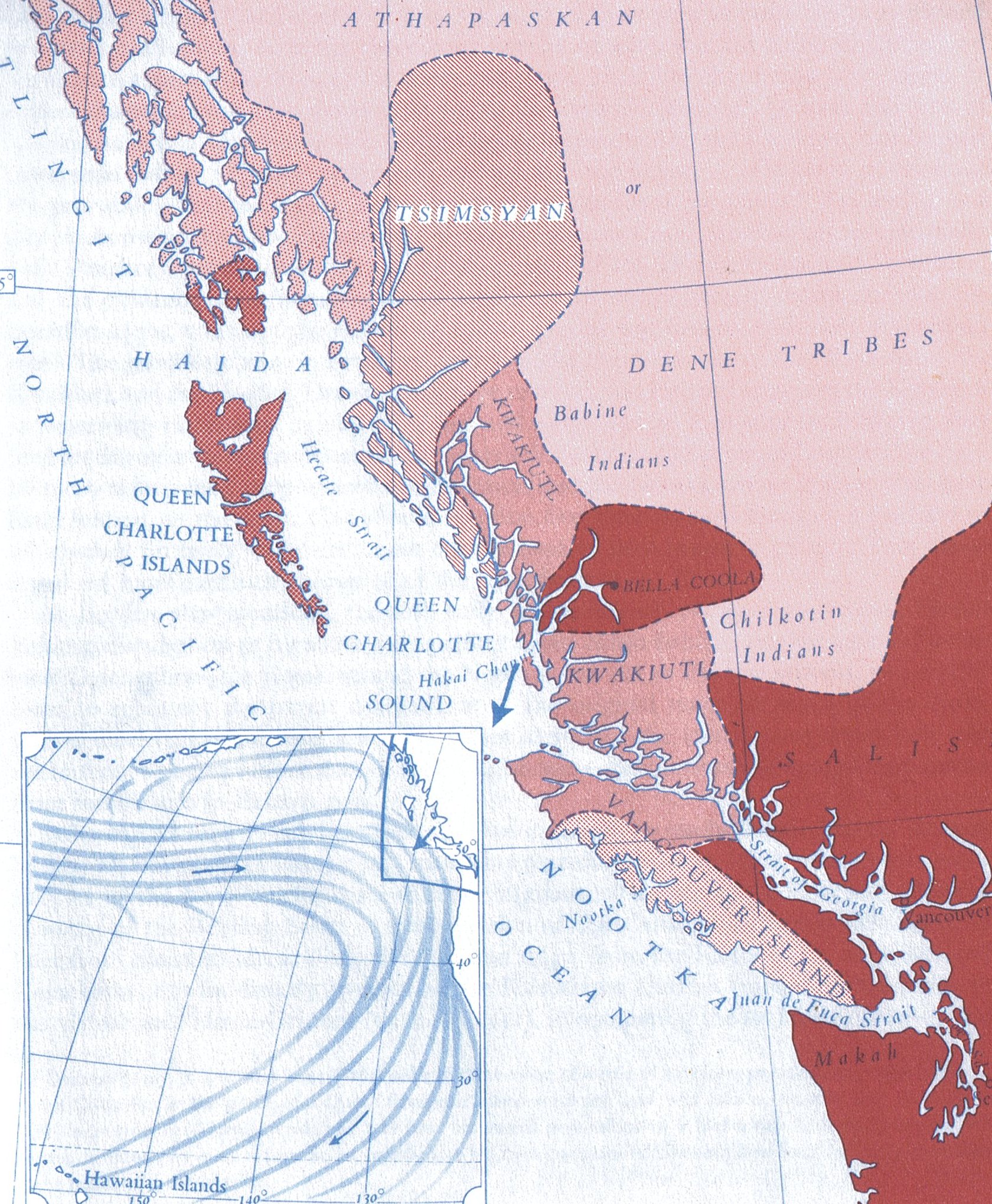

In a general world atlas (Philip 1934, p. 191) I checked up on the principal straits between the islands in the Northwest American Archipelago, and, between the Hunter and Calvert Islands, right in the midst of the Kwakiutl territory, was the Hakai Strait. If Hakai had been, for instance, in Europe or Argentina, or if it had been a mountain-ridge or an island, instead of a principal strait among the Northwest Indians of the particular Kwakiutl tribe, then it might well have been attributed to simple coincidence. But if we are actually looking for a certain strait with a certain name, located between the limited number of islands in Kwakiutl territory, and we actually find it there, that it be coincidence can no longer be considered." (Heyerdahl 6)

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||