|

TRANSLATIONS

"... 'When towards morning the Pleiades become visible the dry

season is imminent [for the Arawak of Guiana], Masasikiri

starts his journey and comes to warn people it is time to

prepare their fields.

He makes a whistling sound to which he owns his nickname

Masakiri (sic).

When people hear him at night, they strike their cutlasses with

something, which makes a sound like a bell; in this way they

thank the spirit for his warning ...25

25 According to P. Clastres (who gave me the

information personally), the non-agricultural Guayaki believe in

a trickster-spirit, who is master of honey and armed with an

ineffectual bow and arrows made of ferns. This spirit announces

his approach by whistling and is driven away by noise.

Thus the return of the Pleiades is accompanied by an exchange of

acoustic signals, the contrast between which has some formal

resemblance to that between the two fire-producing techniques,

friction and percussion ..." (From Honey to Ashes)

According to the

Arawaks of Guiana the early morning appearance of the Pleiades

is a signal to start working their fields.

My earlier

suspicion that rhombs in GD53 glyphs depict the 'skin of the

earth mother' (the agricultural fields) is thereby strengthened:

|

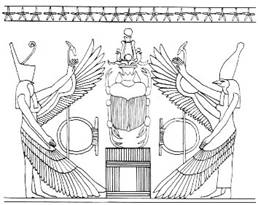

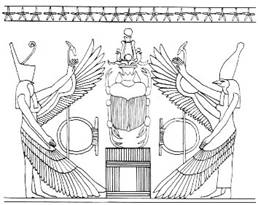

The

goddess at left represents Lower Egypt (low

headgear) and the goddess at right Upper Egypt (high

headgear). Which implies that the center beetle is

located moving from east (bottom) to west (top -

with starry sky above).

The

beetle seems to have emerged through the sun door at

bottom. The 6 legs of the insect become 12 limbs at

their ends.

To

the cardinal points in east and west are here added

the two cardinal points of north (Lower Egypt) and

south (Upper Egypt). In between these 4 cardinal

points we find the surface.

'...

The God Amma, it appeared, took a lump of clay,

squeezed it in his hand and flung it from him, as he

had done with the stars. The clay spread and fell on

the north, which is the top, and from there

stretched out to the south, which is the bottom, of

the world, although the whole movement was

horizontal. The earth lies flat, but the north is at

the top. It extends east and west with separate

members like a foetus in the womb. It is a body,

that is to say, a thing with members branching out

from a central mass. This body, lying flat, face

upwards, in a line from north to south, is feminine.

Its sexual organ is an anthill, and its clitoris a

termite hill ...'

As

we have identified the picture of arms raising the

sun both on Easter Island and in ancient Egypt, it

appears reasonable to suspect that the rhomb figure

in rongorongo represents the surface of the

earth.

'...

Above the door of the temple is depicted a

chequer-board of white squares alternating with

squares the colour of the mud wall. There should

strictly be eight rows, one for each ancestor. This

chequer-board is pre-eminently the symbol of the

'things of this world' and especially of the

structure and basic objects of human organization.

It symbolizes: the pall which covers the dead, with

its eight strips of black and white squares

representing the multiplication of the eight of

human families; the façade of the large house with

its eighty niches, home of the ancestors; the

cultivated fields, patterned like the pall; the

villages with streets like seams, and more generally

all regions inhabited, cleared or exploited by men.

The chequer-board and the covering both portray the

eight ancestors ...' |

As to the

whistling, I remember Kena:

|

... The Masked Booby is silent at sea, but has a

reedy whistling greeting call at the nesting

colonies ...

...

Kena, the name for the booby, is also an eastern

Polynesian name. Line 18 of the creation chant lists

as the mythical parents of kena 'Vie Moko'

and 'Vie Tea' (PH:520). The 'lizard woman' (vie

moko) and her younger sister the 'booby woman' (vie

kena) were considered the originators of

tattooing (ME: 367-368).

The

'white booby woman' (vie kena tea), together

with other deities, protected the eggs of sea birds

(RM:260). She might even be considered to be the

female counterpart of the supreme god Makemake.

In modern Hangaroa, vie kena tea is a

term of endearment for a beloved wife whose

well-rounded body and light skin is being praised

... |

|

Anakena

(presumably ana-kena,

the 'cave' out of which the 'booby'

arrives ?) is located - according to the Easter

Island calendar - at the beginning of the year. |

Another association from whistling

goes to the 4 (as in a rhomb) Pure (kinds of prayer)

emitted by Hotu Matua:

|

... Why are there only 3 Pure emitted by

Hotu Matua? Shouldn't it be an even number? As

O, Ki, and Vanangananga were

three of a quartet we miss Pure Henguingui.

Maybe

it has something to do with the 3 X-time glyphs?

There

are 4 ghostly beams of light in Aa1-13, but there

are only 3 'fruits' (hua, offspring) as

'passengers' in the canoe of Aa1-14

...

...

RAP. henguingui is synonymous with MGV.

henguingui 'to whisper, to speak low' and goes

back to west Polynesian forms (SAM. fenguingui

'to talk in a low tone'; UVE. fegui

'murmurer'). In many of the Polynesian languages,

ki is the spoken word; in some few, ki

refers to the process of thinking; (MGV., MAO.,

HAW.) and in some instances, it indicates special

noises (MQS. ki 'to whistle with two

fingers'; SAM. 'i 'to call like a bird'; TON.

ki 'to squeal'). Generally, o is the

affirmative answer to the caller, while

vanangananga indicates repeated speaking.

The four spirits represents, on one hand, the sound

scale of empty conch shells and, on the other hand,

a classification of types of prayers ...

By

going back to adjacent Polynesian idioms, as

wordplays for topographic features of the area of

the landing site. 'Pure O' permits a wordplay

with MAO. pūreo (i.e., purero 'that

which sticks out of the water'), 'Pure Ki'

with MAO. pureki (i.e., pūrei 'an

isolated rock'), while 'Pure Vanangananga'

brings to mind TUA. vanavana 'protuberance';

TAH. vanavana 'rough, ragged'.

Put

differently, the names of the three ghostly

emissaries, which are actually forms of prayer,

point to tangible objects in the environment, such

as the cliffs and reefs in the water of the bay,

which may have caused the damage done to the stone

figure of the ancestor. The accident must have

occured where the otherwise sandy beach of the

landing site is bordered by rocky promontories or

where sections of the reef jut out of the water.

If in

our version 'Pure O' is said to have used a

pureva (i.e., a large round stone) to sever

the head of the stone figure, this must be a

wordplay, intended to bring about the fourth pure

association, which would complete the 'pure

tetrade' of spirits living in Vai Hū.

Separating pureva into pure va

indicates noisy talk (compare especially HAW. wā)

or loud laughter (TON., UVE. vā), both forms

of expression that have very little in common with

'prayer' and may instead indicate the failure of the

undertaking. 'Pure Va' is, in this case, the

opposite of 'Pure Henguingui ... |

The arrival of the Pleiades (i

nika) announced new year on Easter Island too. On

side b of Tahua I think the middle of the text represents

this point. On side a we have earlier discussed the possibility

of Aa4-64 marking a new season:

|

|

|

|

|

|

Aa4-63 |

Aa4-64 |

Aa4-65 |

Aa4-66 |

Aa4-67 |

| i to rei - kua

hua ia |

kua hura i te

ragi |

ko te manu kua

moe |

ki to ihe |

e kua puhi ki

te ahi |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Aa4-68 |

Aa4-69 |

Aa4-70 |

Aa4-71 |

Aa4-72 |

| o te nuahine -

mau i te rei |

ko te matariki |

e

hau tea - e hapai ana koe |

i te maitaki -

ko matou hanau |

|

... Metoro's

words at the π

glyph (Aa4-64), kua hura i te ragi, are

worthy of note. One of the few Polynesian words

spread internationally is hula-hula:

|

Hura

1. To fish with a small funnel-shaped

net tied to the end of a pole. This

fishing is done from the shore; fishing

with the same net, but swimming, is

called tukutuku. 2. To be active,

to get moving when working: ka hura,

ka aga! come on, get moving! to

work! 3. Tagata gutu hura, a

flatterer, a flirt, a funny person, a

witty person. Hurahura, to dance,

to swing. Vanaga.

1. Sling. In his brilliant study of the

distribution of the sling in the Pacific

tracts, Captain Friederici makes this

note (Beiträge zur Völker- und

Sprachenkunde von Deutsch-Neuguinea,

page 115b): 'Such, though somewhat

modified, is the case in Rapanui,

Easter Island. The testimony of all the

reporters who have had dealings with

these people is unanimous that stones of

two to three pounds weight, frequently

sharp chunks of obsidian, were thrown by

the hand; no one mentions the use of

slings. Yet Roussel includes this weapon

in his vocabulary and calls it hura.

In my opinion this word can be derived

only from the Mangareva verb kohura,

to throw a stone or a lance. So far as

we know Rapanui has received its

population in part by way of Mangareva.'

To this note should be added the

citation of kirikiri ueue

as exhibiting this particular use of

ueue in which the general sense is

the transitive shake. 2. Fife, whistle,

drum, trumpet, to play; hurahura,

whistle. P Mq.: hurahura, dance,

divertissement, to skip. Ta.: hura,

to leap for joy. Pau.: hura-viru,

well disposed. Churchill.

H. Hula, a swelling, a

protuberance under the arm or on the

thigh.

Churchill

2. |

|

Kiri

Skin;

bark; husk; kiri heuheu, downy

skin; kiri mohimohi (also kiri

magó), smooth hairless skin.

Kirikiri miro, multicoloured.

Vanaga.

Skin,

hide, bark, surface; kiri ekaeka,

leprous; kiri haraoa, bran;

kiri hurihuri, negro; kiri maripu,

scrotum; kiri ure; prepuce.

P Pau.: kiri, bark. Mgv.: kiri,

skin, bark, leather, surface, color,

hue. Ta.: iri, skin, bark,

leather, planking. Kirikiri,

pebble, gravel, rounded stone, sling

stone; kikiri, pebble. P Pau.:

kirikiri, gravel, stony, pebbly.

Mgv.: kirikiri, gravel, small

stones, shingle. Ta.: iriiri,

gravel, stony, rough. Kirikirimiro:

ragi kirikirimiro, sky dappled

with clouds. Kirikiriteu, soft

gray tufa ground down with sugar-cane

juice and utilized as paint T.

Kiriputi (kiri - puti)

cutaneous, kiriputiti, id.

Kirivae (kiri - vae

1), shoe. Churchill. |

|

Ue

Uéué,

to move about, to flutter; he-uéué te

kahu i te tokerau, the clothes

flutter in the wind; poki oho ta'e

uéué, obedient child. Vanaga.

1. Alas. Mq.: ue, to groan. 2. To

beg (ui). Ueue: 1. To

shake (eueue); kirikiri ueue,

stone for sling. PS Pau.: ueue,

to shake the head. Mq.: kaueue,

to shake. Ta.: ue, id. Sa.:

lue, to shake, To.: ue'í, to

shake, to move; luelue, to move,

to roll as a vessel in a calm. Niuē:

luelue, to quake, to shake. Uvea:

uei, to shake; ueue, to move.

Viti: ue, to move in a confused

or tumultous manner. 2. To lace.

Churchill. |

If

the sky (ragi) is shaken (ueue) or

leaping (hura), that sounds a lot like when

mother Earth is shaking her breasts:

... It

was an old Maori belief that a change of seasons was

often facilitated by earthquakes. Ruau-moko,

a god of the Underworld, was said to bring about

changes of season, punctuating them with an

earthquake. Or as another Maori saying summed up the

matter, 'It is the Earth-mother shaking her breasts,

and a sign of the change of season.' ...

|

Ru

A chill, to shiver, to shudder, to

quake; manava ru, groan. Ruru,

fever, chill, to shiver, to shake, to

tremble, to quiver, to vibrate,

commotion, to apprehend, moved, to

agitate, to strike the water, to print;

manava ruru, alarm; rima ruru,

to shake hands. P Pau.: ruru, to

shake, to tremble. Mgv.: ru, to

shiver with cold, to shake with fever,

to tremble. Mq.: ú, to tremble,

to quiver. Ta.: ruru, to tremble.

Churchill.

Ruru,

to tremble, an earthquake. Sa.: lūlū,

lue, to shake. To.: luelue,

to roll; lulu, to shake. Fu.:

lulū, to tremble, to shake, to

agitate. Niuē: luelue, to shake;

lūlū, to shake, to be shaken.

Nuguria: ruhe, motion of the

hands in dancing; luhe henua, an

earthquake. Uvea, Ha.: lu,

lulu, lululu, to shake, to

tremble, to flap. Fotuna: no-ruruia,

to shake. Ma.: ru, ruru,

to shake, an earthquake. Ta., Rarotonga,

Rapanui, Pau.: ruru, to shake, to

tremble. Mgv.: ru, to tremble;

ruru, to shake. Mq.: uu, to

shake the head in negation; uuuu,

to shake up. Uvea: ue i, to

shake; ueue, to move. Rapanui:

ueue, to shake. Churchill 2. |

|

The nickname Masakiri sounds

very much like a variant of Matariki. Heyerdahl has

proven (as far as this is possible) that South America had

contacts with Easter Island and the rest of Polynesia, and that

the Polynesians originated in America (not in Asia). Therefore

it is not unthinkable that Matariki and Masakiri

- both meaning the Pleiades - are related words. The change

between s and t is not impossible, likewise the

shifting of syllables (metathesis), riki contra kiri, are

common in the evolution of languages.

In addition we know that not only

the Polynesians but also the South American Indians enjoyed

playing around with their languages:

"... The Indians of

eastern Bolivia 'like to borrow foreign words, with the result

... that their language is constantly changing; the women do not

pronounce the consonants s but always change it into an

f' (Armentia, p. 11).

More than a century

ago, Bates noted (p. 169) in connection with the Mura,

among whom he had lived: 'When the Indians, both men and women,

talk together, they seem to delight in inventing new

pronounciations and in distorting words. Everybody laughs at

these slang inventions, and the new terms are often adopted. I

have observed the same thing during long sailing trips with

Indian crews.'

An amusing

comparison with these remarks is to be found in a letter, full

of Portuguese words, that Spruce wrote from a Uaupés

village to his friend Wallace, who was by that time back in

England: 'Don't forget to tell me how you are progressing in the

English language and whether you can already make yourself

comprehensible to the natives ...' Wallace gives the following

explanatory commentary:

When we met at São

Gabriel ... we had noticed that we were quite incapable of

conversing together in English, without using Portuguese words

and expressions which amounted to about a third of our

vocabulary. Even when we made up our minds to speak only in

English, we succeeded in doing so only for a few minutes and

with difficulty and as soon as the conversation became animated

or it was necessary to recount an anecdote, Portuguese

reasserted itself! ...

Such linguistic

osmosis, with which travellers and expatriates are well

acquainted, must have played a considerable part in the

evolution of the Amercian languages and in the linguistic

conceptions of the natives of South America.

According to a

Kalina theory noted by Penard (in Goeje, p.32): 'vowels

change quicker than consonants, because they are thinner,

swifter, more liquid than the resistant consonants, but in

consequence their yumi close themselves sooner, which

means they return to their source more rapidly ..." (From Honey

to Ashes)

|