|

TRANSLATIONS

Two 'staffs' (or

'poles') on top

of each other

closely

resembles our

own idea about a

north and a

south pole.

We should here

remember how the

Maori and

Moriori

fishermen (which

are close

together

geographically),

shared the Haida

Gwaii concept of

staffs on top of

each other:

|

Ana

1.

Cave.

2.

If.

3.

Verbal

prefix:

he-ra'e

ana-unu

au i

te

raau,

first

I

drank

the

medicine.

Vanaga.

1.

Cave,

grotto,

hole

in

the

rock.

2.

In

order

that,

if.

3.

Particle

(na

5);

garo

atu

ana,

formerly;

mee

koe

ana

te

ariki,

the

Lord

be

with

thee.

Churchill.

Splendor;

a

name

applied

in

the

Society

Islands

to

ten

conspicious

stars

which

served

as

pillars

of

the

sky.

Ana

appears

to

be

related

to

the

Tuamotuan

ngana-ia,

'the

heavens'.

Henry

translates

ana

as

aster,

star.

The

Tahitian

conception

of

the

sky

as

resting

on

ten

star

pillars

is

unique

and

is

doubtless

connected

with

their

cosmos

of

ten

heavens.

The

Hawaiians

placed

a

pillar

(kukulu)

at

the

four

corners

of

the

earth

after

Egyptian

fashion;

while

the

Maori

and

Moriori

considered

a

single

great

central

pillar

as

sufficient

to

hold

up

the

heavens.

It

may

be

recalled

that

the

Moriori

Sky-propper

built

up a

single

pillar

by

placing

ten

posts

one

on

top

of

the

other.

Makemson. |

It is not

impossible to

imagine how the

horizontal poles

(as in Tahiti

and Hawaii) -

which are

space-oriented

(at corners

around the

horizon) - must

be placed on top

of each other:

Visualizing the

progress of

cyclical solar

time, beginning

at new year with

the first pole

(Sirius), then

advancing to

next station

when sun has

moved up a bit

and another

'staff' is

needed on top of

the first one to

hold the sun

up, then

continuing all

the way up to

midsummer when

all sections are

needed.

In winter the

staffs are

needed on the

other side of

earth. After

midsummer they

are therefore

gradually

disassembled

here.

Now to moa:

I have not

earlier in the

glyph dictionary

used the first

page to present

different types

of glyphs like

this. In the

glyph catalogue

the table above

is presented

already at

manu rere.

Another similar

table is

presented at

tagata.

|

A

few

preliminary

remarks

and

imaginations:

1.

The

picture

in

moa

glyphs

appear

to

show

a

cock

-

not

a

hen

(moa

uha)

and

not

a

youngster

(moa

taga)

but

a

fully

grown

and

potent

rooster

(moa

to'a):

"While

the

dog

and

the

pig

existed

only

in

the

traditions

as

the

shadows

of

the

past,

the

domestic

fowl

(moa)

that

were

brought

along

achieved

a

position

of

supreme

importance.

As a

matter

of

fact,

they

dominated

the

island's

economy

to

the

point

that

one

is

tempted

to

speak

of a

prevailing

'economy

of

fowl'!

Their

influence,

in

its

many

ramifications,

touched

every

aspect

of

life

of

the

Easter

Islanders,

including

the

socioeconomic

and

the

ideologic.

As

the

only

permanent

livestock,

they

were

an

essential

part

of

the

islanders'

subsistence.

All

sources

count

moa

(Gallus

sp.)

among

the

animals

imported

by

Hotu

Matua,

and

the

terminology,

including

figurative

terms,

is

solidly

rooted

in

the

Polynesian

language.

Moa

means

'fowl'

in

general

as a

generic

term,

but

it

also

means

'rooster'.

On

the

other

hand,

the

name

for

'hen'

is

formed

by

adding

uha,

the

general

Polynesian

addition

for

female

animals.

Specific

names

are

formed

by

adding

attributes

to

moa

-

such

as

moa

maanga

and

moa

rikiriki

for

'chicken',

moa

tanga

for

'young

hen

or

rooster',

and

moa

toa

for

an

especially

splendid

'rooster'.

There

is

an

extensive

terminology

dealing

with

characteristics

of

the

anatomy

and

the

different

types

of

plumage.

It

is

also

truly

amazing

to

what

extent

types

and

scenes

from

the

world

of

fowl

were

projected

upon

people

and

situations.

Some

examples

of

'zoomorphic

patterns

of

speech'

will

serve

to

illustrate

the

point.

An

adopted

child

is a

'chick

that

is

being

nourished'

(maanga

hangai).

Formerly,

a

marriageable

daughter,

as

well

as a

beloved

wife,

was

called

a

'hen'

(uha).

It

was

a

mark

of

distinction

for

a

grown

son

or a

brave

young

man

to

be

referred

to

as a

'rooster'

(moa)

..."

(Barthel

2)

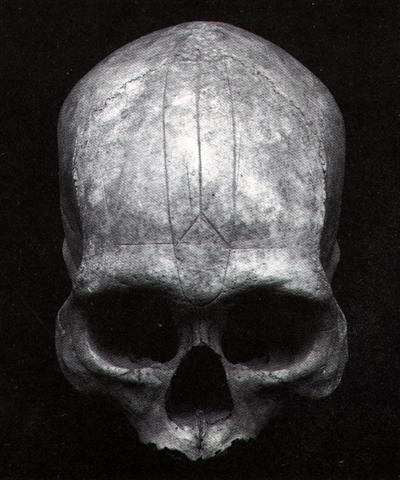

The

virility

of a

cock

was

intertwined

with

that

of a

chief:

"Up

to

the

present

time,

fertility

spells

for

fowls

have

played

an

important

role.

Especially

effective

were

the

so-called

'chicken

skulls'

(puoko

moa)

-

that

is,

the

skulls

of

dead

chiefs,

often

marked

by

incisions,

that

were

considered

a

source

of

mana.

Their

task

is

explained

as

follows:

'The

skulls

of

the

chiefs

are

for

the

chicken,

so

that

thousands

may

be

born'

(te

puoko

ariki

mo

te

moa,

mo

topa

o te

piere)

...

As

long

as

the

source

of

mana

is

kept

in

the

house,

the

hens

are

impregnated

(he

rei

te

moa

i te

uha),

they

lay

eggs

(he

ne'ine'i

te

uha

i te

mamari),

and

the

chicks

are

hatched

(he

topa

te

maanga).

After

a

period

of

time,

the

beneficial

skull

has

to

be

removed,

because

otherwise

the

hens

become

exhausted

from

laying

eggs."

(Barthel

2)

|

The 'wood' from

the old 'snag'

is used to light

the new fire:

|

...

The

world

of

rottenness

is

the

world

of

the

mortals.

The

Raw

and

the

Cooked:

'...

With

reference

to

the

contrast

between

rock

and

decay,

and

its

symbolic

relation

with

the

duration

of

human

life,

it

may

be

noted

that

the

Caingang

of

southern

Brazil,

at

the

end

of

the

funeral

of

one

of

their

people,

rub

their

bodies

with

sand

and

stones,

because

these

things

do

not

rot.

'I

am

going

to

be

like

stones

that

never

die',

they

say'.

'I

am

going

to

grow

old

like

stones

...'

Stone

is

tau

in

Rapanui,

as

eg

in

Tautoru

(The

Belt

of

Orion)

and

Tauono

(The

Pleiades).

Stars

are

reliable

and

permanently

there

(immortal).

But

tau

is

also

'season'

(or

rather

the

'produce

of

the

season').

The

seasons

are

also

reassuringly

reliable.

Cooking

implies

mortality,

The

Raw

and

the

Cooked:

'...

comparison

between

the

Apinaye

and

Caraja

versions,

which

tell

the

story

of

how

men

lost

immortality,

provides

an

additional

interest,

in

that

it

establishes

a

clear

link

between

this

theme

and

that

of

the

origin

of

cooking.

In

order

to

light

the

fire,

dead

wood

has

to

be

collected,

so a

positive

virtue

has

to

be

attributed

to

it,

although

it

represents

absence

of

life.

In

this

sense,

to

cook

is

to

'hear

the

call

of

rotten

wood'.

But

the

matter

is

more

complicated

than

that:

civilized

existence

requires

not

only

fire

but

also

cultivated

plants

that

can

be

cooked

on

the

fire.

Now

the

natives

of

central

Brazil

practice

the

'slash

and

burn'

technique

of

clearing

the

ground.

When

they

cannot

fell

the

forest

trees

with

their

stone

axes,

they

have

recourse

to

fire,

which

they

keep

burning

for

several

days

at

the

base

of

the

trunks

until

the

living

wood

is

slowly

burned

away

and

yields

to

their

primitive

tools.

This

preculinary

'cooking'

of

the

living

tree

poses

a

logical

and

philosophical

problem,

as

is

shown

by

the

permanent

taboo

agains

felling

'living'

trees

for

firewood.

In

the

beginning,

so

the

Mundurucu

tell

us,

there

was

no

wood

that

could

be

used

for

fires,

neither

dry

wood

nor

rotten

wood:

there

was

only

living

wood

...

Therefore

only

dead

wood

was

legitimate

fuel.

To

violate

this

regulation

was

tantamount

to

an

act

of

cannibalism

against

the

vegetable

kingdom.' |

|

...

'When

I

discussed

the

theme

of

man's

mortality

in

the

South

American

myths,

I

showed

that

they

developed

it

either

in

the

form

of

the

impossibility

of

rejuvenation

or

resurrection,

or

in

the

complementary

form

of

premature

aging

...

The

North

American

myths

belonging

to

the

lewd

grandmother

cycle

retain

this

distinction,

since,

in

the

first

type

(the

provocative

neighbour),

a

very

young

hero

suddenly

loses

all

his

teeth

and

so

becomes

a

prematurely

old

man,

whereas

in

the

third

(the

incestous

grandmother),

a

very

old

heroine

succeeds

in

getting

rid

of

her

wrinkles;

but

even

the

most

famous

shamans

fail

to

give

her

back

her

teeth:

the

absence

of

teeth

is

responsible

for

a

second

death,

and

this

time

resuscitation

is

no

longer

possible

...

It

can

be

noted

in

passing

that

the

Coast

Salish

believed

in a

similar

opposition

between

death

from

sickness

and

death

by

decapitation:

only

the

second

was

irrevocable

...' |

Headhunters

want to kill

their

enemies for

good. The

enemy will

thereby be

robbed of

his

vitality,

which will

be

transferred

to the

headhunter.

The

possessor is

the owner.

What is

possessed is

an attribute

of the

possessor.

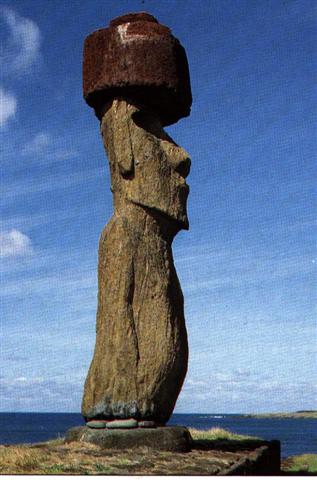

| 2. The function of cocks and chiefs to ascertain the arrival of 'fruits' (hua) of all kinds on the island has made me conclude there is a wordplay involved between moa and moai (the statues). I read moai as moa-î, where the meaning of -î is 'full', 'abound', 'be plentiful'. For example: ki î te îka i uta, 'as there are lots of fish on the beach'. Makemson has suggested the statues, standing high and erect, to have been raised to guarantee a fertile land:

... the embodiment of sunlight thus becomes, in the form of a carved human male figure, the probable inspiration for the moai as sacred prop between Sky and Earth. The moai as Sky Propper would have elevated Sky and held it separate from Earth, balancing it only upon his sacred head. This action allowed the light to enter the world and made the land fertile ...

The statues are made from stone: mae'a Matariki, Pleiades-stones, according to Churchill. When the Pleiades rose in the east before the sun the male part of the year, the time of rising sun was announced:

... I think it is probable that the Rapa Nui ritual calendar, as that of the Maori, Mangarevans, Samoans, Tongans and other Polynesians began in July following the rising of the Pleiades. On Rapa Nui and many other islands, the Pleiades were called Matariki...

According to Heyerdahl, when the islanders were asked why there were no ure (penis) on the stone giants an old man calmly replied: 'A moai cannot have two ure, he is one himself.' As to the form of the moai statues a famous myth confirms:

"Métraux quotes a Rapa Nui legend in which carvers from Hotu Iti (eastern sector) journeyed to the western sector to seek the advice of a master carver. They were perplexed about how to resolve the difficult problem of carving the statue neck. He advised them to seek the answer by viewing their own bodies. They did so, and discovered that the model for the statue neck was the penis (ure)." (Van Tilburg)

|

The circuit

is hua -

moa - hua -

moa etc.

The 'chicken

skulls'

(heads of

dead chiefs)

are used for

generating a

new

generation

and the new

generation

will in turn

generate new

chiefs. I

think the

1st half of

the year,

counted from

winter

solstice, is

the season

of hua -

moa and

the 2nd half

the season

moa - hua.

|