|

TRANSLATIONS

I get the idea

that in Aa8-78 the 'feet' belong to a bird, and the left

'foot' is longer as in unmarked GD11 in B and G:

On the other

hand, in A unmarked GD11 has feet more like those in

Aa8-27. Furthermore, the fishes tend to have tail-fins

similar to what we see in Aa8-78:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Ab2-32 |

Ab2-67 |

Ab5-45 |

Ab5-60 |

Ab6-5 |

Ab6-10 |

The 'feet' in

Aa6-29 maybe are turtle's feet.Via Haga Hônu

marking autumn equinox (while Haga Takaure is

expressing spring equinox), I imagine the feet of the

turtle to originate from the shape of waning moon (like

an overturned canoe).

The waxing

moon would then be like a canoe right side up like the

moon sickle at the top of Aa8-78.

In vai

(GD16) we may have an image with full 'moon' (midsummer,

noon) in center, waxing moon at the top and waning at

bottom:

The difference

between growing and waning sun as expressed by vai

may then be suggested by how the sickles are located and

whether they are seen or not:

Eb3-7 (left)

and Eb4-26 (right) are examples (spring respectively

autumn). The top is the waxing phase of the sun and the

bottom the waning phase. With a single rim the phases of

the moon can be similarly expressed.

I have just

written about GD16 in the dictionary:

|

A few preliminary remarks and imaginations:

1.

This type of glyph possibly

illustrates the concept of 'the

living water of Tane' (vai

ora a Tane). There may be water in

the middle oval and there are four flames

like the reflexes from water. The number

four may indicate the four 'corners' of our

'earth', which is the receiving part.

The sun was associated with water among

other ancient peoples too, e.g. among the

early Babylonians and among the Maya

indians:

"But

beyond their role as points of communication

with the Underworld, James Brady of George

Washington University has told us that in

the Maya mind caves were intimately

associated with mountains, and that it is in

such caves that it was and still is believed

that fertilizing rain is created before

being sent into the sky; even today

ceremonies are held inside them at the onset

of the rainy season." (The Maya) |

| "...Tane,

under his name of Tane-te-waiora,

is the personified form of sunlight, and

the waiora a Tane is merely an

esoteric and emblematic term for

sunligth. The word waiora carries

the sense of health, welfare, soundness.

In eastern Polynesia the words vai

and vaiora mean 'to be, to

exist'. Warmth, sayeth the Maori, is

necessary to all forms of life, and the

warmth emitted by Tane the

Fertilizer is the waiora or

welfare of all things." (Best)

A straightforward

translation of vai, though, is

(sweet) water and ora means life.

I.e. living-water of Tane.

Spelling conventions makes Tane

into Kane in Hawaii.

"Centuries ago there

lived in Hawaii-of-the-green-hills a

chieftain whose name has been forgotten.

He is known only by the place from which

he came, Hawaii-loa, Far-away

Hawaii. His home was on the coast of

Kahiki-ku, Border-of-the-rising-Sun,

which lay eastward of the region where

mankind was first created, the

Land-of-the-living-water of the god

Kane." (Makemson) |

|

2.

The sun is passing

through an 'eye' in order to travel

into 'the world of darkness'. It is

the door to the yonder world, the

world of 'sleep' where 'dreams' are

living. There the sun is refreshing

himself, fetching his 'water'.

"Alice was beginning

to get very tired of sitting by her

sister on the bank and of having

nothing to do: once or twice she had

peeped into the book her sister was

reading, but it had no pictures or

conversations in it, 'and what is

the use of a book', thought Alice,

'without pictures or conversations?'

So she was

considering, in her own mind (as

well as she could, for the hot day

made her feel very sleepy and

stupid), whether the pleasure of

making a daisy-chain would be worth

the trouble of getting up and

picking the daisies, when suddenly a

White Rabbit with pink eyes ran

close by her.

There was nothing so

very remarkable in that; nor

did Alice think it so very

much out of the way to hear the

Rabbit say to itself 'Oh dear! Oh

dear! I shall be too late!' (when

she thought it over afterwards it

occurred to her that she ought to

have wondered at this, but at the

time it all seemed quite natural);

but, when the Rabbit actually

took a watch out of its

waistcoat-pocket, and looked at

it, and then hurried on, Alice

started to her feet, for it flashed

across her mind that she had never

before seen a rabbit with either a

waistcoat-pocket, or a watch to take

out of it, and was just in time to

see it pop down a large rabbit-hole

under the hedge. In another moment

down went Alice after it, never once

considering how in the world she was

to get out again." (Carroll)

In South America the motif of the

weeping eye may have a

connection with the Eastern

Polynesian concept of vaiora a

Tane. At the

archeological site of Orongo

(Heyerdahl 4) was found two

paintings of faces, similar to those

on ao paddles:

The movements of the eye are quick -

which means full of life.

As I remember it

Posnansky was certain that the

'tears' was a way of showing how the

eyes of the sun god were quickly

moving, not really tears at all but

'movement'. |

|

3.

The sky is like a kind of roof.

Above the roof the gods have

their abode (heaven). They can

fly up there. Maybe the stars

are holes in the roof and if so

then the stars are evidence that

the gods live in a glorious

light.

"Two men came to a hole in the

sky. One asked the other to lift

him up. If only he would do so,

then he in turn would lend him a

hand. His comrade lifted him up,

but hardly was he up when he

shouted for joy, forgot his

comrade and ran into heaven.

The other could just manage to

peep over the edge of the hole;

it was full of feathers inside.

But so beautiful was it in

heaven that the man who looked

over the edge forgot everything,

forgot his comrade whom he had

promised to help up and simply

ran off into all the splendour

of heaven." (Arctic Sky)

The light flaming from the

sun is like the light from the

stars - it is a sign of fire

(which in turn is symbolized by

feathers).

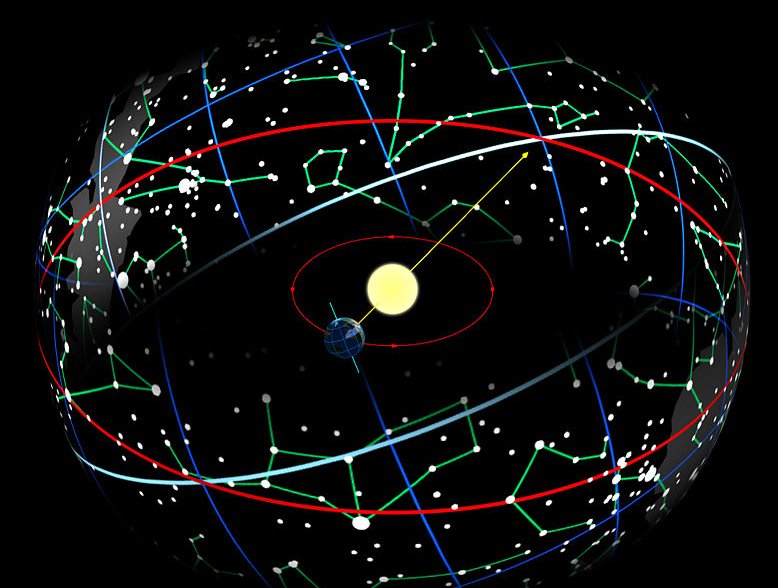

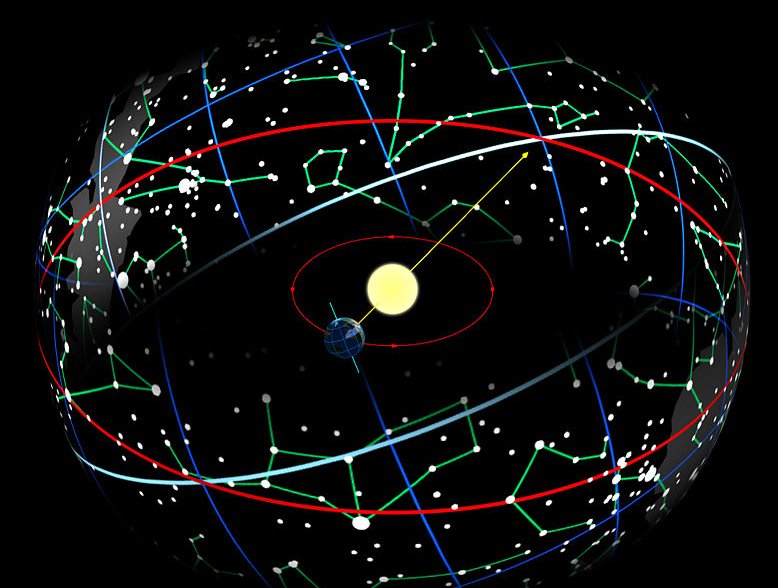

Cultural (non-civilized) man

knew how the sky roof slowly

revolved and that early each

morning (or evening) the

movement could be observed in

the way the sky had changed its

position a little bit since

yesterday.

Against the background of the

starry sky the movement of the

sun could be regarded as

constant. Every morning the

sun rose at dawn and every

evening he went down at the

other end of the sky.

Possibly, the canoe in which

the sun travelled was like a big

hole in the sky. The hole moved

slowly to keep the sun rising

and setting at the correct time

depending on season.

(Source:

Wikipedia) |

| Obviously the

Polynesians were well aware

of the concept of relative

movement. A gradual and slow

movement of the sun at the

horizon as observed in the

morning (or evening) could

be related to the slowly

revolving sky roof, thereby

coordinating the position of

the sun with the season and

with the position of the

star roof.

This was more easy to

grasp (and equally valid)

than the double movements of

the sun (daily and seasonal)

against a fixed sky roof (or

a view of earth

simultaneously circling

around the sun and its own

axis).

A quaint detail which

assures us about how the old

sea-farers preferred the

model of a slowly moving sky

rather than a model with

more complex movements for

sun canoe and earth is the

fact that when they

themselves travelled by

canoe to some distant island

they regarded their canoe to

stand still while the island

slowly came closer.

Navigation was more easy

that way:

"... In

traditional navigational

schools on Puluwat in

the Caroline Islands,

students learn how to sail

outrigger canoes. As

Puluwat sailors

conceptualize a voyage

between two islands, it is

the islands that move rather

than the canoe: the starting

point recedes as the

destination approaches :.."

(D'Alleva) |

We can then remember

how Sun is

symbolized in this

calendar:

|

Sun |

|

|

Jupiter |

|

|

|

Eb7-3 |

Eb7-4 |

Eb7-11 |

Eb7-12 |

|

Moon |

|

|

Venus |

|

|

|

Eb7-5 |

Eb7-6 |

Eb7-13 |

Eb7-14 |

|

Mars |

|

|

Saturn |

|

|

|

Eb7-7 |

Eb7-8 |

Eb7-15 |

Eb7-16 |

|

Mercury |

|

|

Sun

and

Jupiter

are here

referred

to by

other

signs

than

GD11,

while

the

rulership

of

Saturn

is

indicated

by a

complex

glyph

based on

GD11.

|

|

Eb7-9 |

Eb7-10 |

|

|

In the Keiti

calendar for the

year GD16

appears in the

6th and the 15th

periods:

|

|

"The Maori

recognized

two main

divisions of

the year:

winter or

takurua,

a name for

Sirius which

then shone

as morning

star, and

summer,

raumati

or

o-rongo-nui,

'of the

great

Rongo',

god of

agriculture.

They

occasionally

recognized

spring as

the digging

season

koanga,

from ko,

the digging

stick or

spade. The

autumn or

harvest

season was

usually

spoken of as

ngahuru,

'tenth'

(month),

although it

was

considered

to include

also the

last two

months of

the year.

Mahuru

was the

personification

of spring."

(Makemson)

"The Maori

term

o-rongo-nui

was

undoubtedly

applied to

summer as in

phrases such

as te ra

roa o te

marua-roa o

te

o-rongo-nui,

'the long

days (ra,

Sun) of the

summer

solstice';

but it was

also

extended to

cover the

months of

spring and

early summer

as well as

those of

late summer

and fall.

This is

evident from

such

statements

in the

legends as:

'That bird

is a cuckoo,

and that is

the bird of

matahi o

te tau o

o-rongo-nui',

i.e., of the

first month

of the

summer

season,

although in

New Zealand

the cuckoo,

like the

robin in the

north

temperate

zone, was

the

harbinger of

spring.

Also, 'Hine-rau-wharangi'

was born in

the month

Ao-nui

(first

light) of

the

o-rongo-nui'.

Among the

Takitumu

tribe

Ao-nui

was the name

for

May-June,

the first

month of the

year which

belonged to

late fall or

early

winter.

Rongo

was the name

for June in

the Chatham

Islands and

began the

Moriori

year."

(Makemson) |

| In Barthel 2 a summary is given over the months on Easter Island (according to the structure of a modern calendar). I have adapted the table somewhat. Red means the 6 months when sun is 'present': |

|

1st quarter |

2nd quarter |

3rd quarter |

4th quarter |

|

He Anakena (July) |

Tagaroa uri (October) |

Tua haro (January) |

Vaitu nui (April) |

|

Same as the previous month. |

Cleaning up of the fields. Fishing is no longer taboo. Festival of thanksgiving (hakakio) and presents of fowl. |

Fishing. Because of the strong sun very little planting is done. |

Planting of sweet potatoes. |

|

Hora iti (August) |

Ko Ruti (November) |

Tehetu'upú (February) |

Vaitu poru (May) |

|

Planting of plants growing above the ground (i.e., bananas, sugarcane, and all types of trees). Good time to fish for eel along the shore. |

Cleaning of the banana plantations, but only in the morning since the sun becomes too hot later in the day. Problems with drought. Good month for fishing and the construction of houses (because of the long days). |

Like the previous month. Some sweet potatoes are planted where there are a lot of stones (pu). |

Beginning of the cold season. No more planting. Fishing is taboo, except for some fishing along the beach. Harvesting of paper mulberry trees (mahute). Making of tapa capes (nua). |

|

Hora nui (September) |

Ko Koró (December) |

Tarahao (March) |

He Maro (June) |

|

Planting of plants growing below the ground (i.e., sweet potatoes, yams, and taro). A fine spring month. |

Because of the increasing heat, work ceases in the fields. Time for fishing, recreation, and festivities. The new houses are occupied (reason for the festivities). Like the previous month, a good time for surfing (ngaru) on the beach of Hangaroa O Tai. |

Sweet potatoes are planted in the morning; fishing is done in the afternoon. |

Because of the cold weather, nothing grows (tupu meme), and there is hardly any work done in the fields. Hens grow an abundance of feathers, which are used for the festivities. The time of the great festivities begins, also for the father-in-law (te ngongoro mo te hungavai). There is much singing (riu). |

|

The spelling of the names of the months are according to Vanaga. |

|

| By now it must be clear that GD16 (vai) is a symbol for the sun. There remains, though, a question to be answered: Why is there only one oval in Hb9-18 (instead of the normal two)?

| Sunday |

|

|

|

|

|

| Hb9-17 |

Hb9-18 |

Hb9-19 |

Hb9-20 |

Hb9-21 |

|

|

Only three glyphs in the P calendar. |

|

| Pb10-29 |

Pb10-30 |

Pb10-31 |

Answer: Because the calendar of the week is also a calendar for the planets. Planets cannot be seen during the day, only in the night. Logic has presumably made the creator of the H text to deduce that sun cannot be visible in a calendar for the week.

Therefore, he decided to chose a symbol for the invisible sun, the sun below the horizon, the sun during the night. The creator of the P text, however, seems to have missed the point, because also in Pb10-29 'night' is written by way of hatchmarks across GD37, henua. |

| Summary: The sun is symbolized by GD16 glyphs.

The label vai

for GD16 has been chosen because Metoro pointed to the

sun as the source of the important rain. Although also other glyph

types was referred to as vai by Metoro, the more

rounded versions of GD16, as for instance in the calendars for the

year in E and G, definitely appears to be connected with water.

Other versions of

GD16 are not so rounded, and the idea probably then is

not water but the canoe of the sun. In rei miro (GD13) the

sun canoe is seen as from afar (sideways), in GD16 it appears as

seen close by.

GD16 with a single

rim means the invisible sun (below the horizon). On side a of

Tahua GD16 glyphs have double oval rims, but on side b single rims. |

|