|

TRANSLATIONS

When the Stranger King arrives over the sea to take command over this land and our queen, he must have been born on the other side of the horizon. He is the sun born at new year on the other side of the earth. Likewise, a baby will be born on this land at midsummer. He cannot be king here, the old king is still living. Therefore he must depart to another land on the other side of the horizon. What a powerful incentive to migrate across the sea in all directions! Next page in the glyph dictionary:

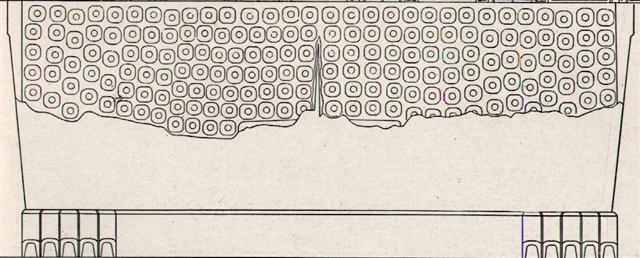

On the Pachamama skirt there are 3 * 59 = 177 signs, here we have 4 * 59 = 236 signs. If the idea is to measure half a year, then 177 is close, while 236 is off the mark. 177 is less than 182, which agrees with the fact that south of the equator summer is shorter than winter. Pachamama is facing us, that means her front - i.e. the time sun is present (summer) - measures 177. In G the first half is measured by the text on side a, from Ga1-26 to Gb1-6, as 210 glyphs. A second half should also be 210 glyphs, together reaching 420 (7 flames of the sun). 261 + 210 = 471 is 51 more than 420. According to the skirt of Pachamama there are 25 + 25 = 50 signs at the beginning and end of the cycle:

We must not be deceived by the fact that there are 7 columns with 5 signs at right in the picture, 2 of them belong to the group with 16 (columns 8-10):

7 * 5 = 35 is, however, also a message delivered of course. 420 / 35 = 12. The skirt can be read more than in one way. The central part of the skirt surely illustrates 'high summer' (maby both by reading the skirt as the cycle of sun over the year respectively the day or by reading the skirt as the cycle of the moon). The midpoint of high summer is characterized by a rift, or visualized from the other direction, as a mountain point. Possibly the same kind of sign is in the center of Akbal (night):

The beginning and end of the Pachamama skirt cycle has 25 + 25 signs, as symmetric season straddling 'new year'. We recognize the fundamental pattern, that 'night' is divided in two equal parts. The structure of the G text is similar to that in the Pachamama skirt: At the center is high summer, while darkness rules the beginning and end. With 25 dark glyphs before Ga1-26 and the Pachamama skirt fresh in mind I counted backwards from the end of side b. Shouldn't there be 25 special glyphs also at the end of the cycle? Yes, there are. Beyond the possible kava glyph in Gb7-31 there are 5 glyphs which precede the 25 glyphs at the end of side b:

A glyph like a canoe (Gb8-4) is the last of the 210 glyphs for the 2nd half of the cycle and in Ga1-25 the same canoe is found again, at the end of a 51 glyph long journey. Gb8-5 is a looking back bird (the only one of its kind in G) which once made me document the 25 following glyphs on a single page. This is what presumably happens on the voyage:

I have red-marked Gb8-11 because I have waited for an opportunity to insert another important item. Beyond these 16 'summer-time' glyphs, arranged in the pattern 2 + 3*2 plus 2 + 2*3, there arrive what I believe are 'winter-time' glyphs, arranged as 4*2 = 8, i.e. light (16) + dark (8) equals 24:

Obviously these 24 glyphs belong together in a pattern with 'growing' at the beginning (illustrated by an open mouth in 2 + 3*2), followed by 'desiccation' (illustrated by hue in 2 + 2*3 - Metoro said e te hue e at the last of the 8 glyphs) -, and then by rain (Ża) and water (vai). The pattern in the last 'season' is 1 + (1+1+1) + (2+1+1) = 8. Metoro's words at Ab6-60--61 are worthy to observe:

His hotu is the only time he mentions what could be king Hotu A Matua. And tagi is weeping:

Is there a general crying because of the fate of the king? Polynesians weep when an old friend arrives, not when he leaves. If we cut 'night' in two equal parts, Ab6-60--61 arrives with 'new year'. His hotu presumably means the new year, not the king. As to iko the word does not 'rhyme' with tagi:

Here the friend has left, been carried off, taken out of the fire (hiko). The old year is no longer. 6 * 60 = 360. ... When Tu'u ko ihu went down to the House of Cockroaches the people were taking the stones from the earth-oven and were throwing out the ends of burning wood. This wood was toromiro. Tu'u ko ihu took two flaming pieces of wood and carried them into that house, into Hare koka. He sat there, and with his sharp pieces of obsidian he carved them into moai kavakava ... |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||