Joseph Campbell (The Masks of God: Primitive Mythology.): ... For the planting folk of the fertile steppes and tropical jungles ... death is a natural phase of life, comparable to the moment of the planting of the seed, for rebirth. As an example of the attitude, we may take the composite picture presented by Frobenius of the sort of burial and reliquary rites that he observed everywhere among the horticulturists of South and East Africa: When an old kinsman of the sib dies, a cry of joy immediately fills the air. A banquet is arranged, during which the men and women discuss the qualities of the deceased, tell stories of his life, and speak with sorrow of the ills of old age to which he was subject in his last years. Somewhere in the neighorhood - preferably in a shady grove - a hollow has been dug in the earth, covered with a stone. It now is opened and there within lie the bones of earlier times. These are pushed aside to make room for the new arrival. The corpse is carefully bedded in a particular posture, facing a certain way, and left to itself then for a certain season, with the grave again closed. But when time enough has passed for the flesh to have decayed, the old men of the sib open the chamber again, climb down, take up the skull, and carry it to the surface and into the farmstead, where it is cleaned, painted red and, after being hospitably served with grain and beer, placed in a special place along with the crania of other relatives. From now on no spring will pass when the dead will not participate in the offerings of the planting time; no fall when he will not partake of the offerings of thanks brought in at harvest: and in fact, always before the planting commences and before the wealth of the harvest is enjoyed by the living. Moreover, the silent old fellow participates in everything that happens in the farmstead. If a leopard kills a woman, a farmboy is bitten by a snake, a plague strikes, or the blessing of rain is withheld, the relic is always brought into connection with the matter in some way. Should there be a fire, it is the first thing saved; when the puberty rites of the youngsters are to commence, it is the first to enjoy the festival beer and porridge. If a young woman marries into the sib, the oldest member conducts her to the urn or shelf where the earthly remains of the past are preserved and bids her take from the head of an ancestor a few kernels of holy grain to eat. And this, indeed, is a highly significant custom; for when this young, new vessel of the spirit of the sib becomes pregnant, the old people of the community watch to see what similarities will exist between the newly growing and the faded life ... ' Frobenius terms the attitude of the first order 'magical', and the latter 'mystical', observing that whereas the plane of reference of the first is physical, the ghost being conceived as physical, the second renders a profound sense of a communion of death and life in the entity of the sib. And anyone trying to express in words the sense or feeling of this mystic communion would soon learn that words are not enough: the best is silence, or the silent rite. Not all the rites conceived in this spirit of the mystic community are as gentle, however, as those just described. Many are appalling, as will soon be shown. But through all there is rendered, whether gently or brutally, an awesome sense of this dual image, variously turned, of death in life and life in death: as in the form of the Basumbwa Chief Death, one of whose sides was beautiful, but the other rotten, with maggots dropping to the ground; or in the Hawaiian tree with the deceptive branches at the casting-off place to the other world, one side of which looked fresh and green but the other dry and brittle ... The powerfully drawn niu in day 59 alludes to the last glyph on side a of the tablet (number 229). In mythic time this Tree of Life was fully grown in the day after St John's Eve (heliacal view) or in the night after Christmans Eve (nakshatra view):

... This [ζ Cancri at Ga2-29] lies on the rear edge of the Crab's shell, and is known as Tegmine, In the Covering; but, if the word be allowable at all, it should be Tegmen, as Avienus is supposed to have had it. Ideler, however, said that Avienus was referring to the covering shell of the marine object, and not to the stellar ... ... The ancient Chinese used to drill holes in turtle shells and then place them in the fire to see what cracks developed. The cracks foretold the future:

Turtles can be associated with earth (the Middleworld) and earth is resistant to fire. The Polynesians had earth-ovens (umu) in which food was prepared. The heavenly firedrill had a turtle at the bottom presumably to isolate the earth from a general conflagration when at new year a fire must be ignited.  ... the tortoise cannot be burnt ... a characteristic which is confirmed objectively by ethnography, since the wolf's trick [in M192] of trying to cook the tortoise while it was lying on its back is based on a method which may seem barbarous but is still current in central Brazil: the tortoise is so difficult to kill that the peasants cook it alive among the hot wood cinders, with its own shell acting as the cooking-dish; the process may last several hours, because the poor beast takes so long to die ... The 'Brutes' (beasts) of early and quick growth later matured to become stable 'Men'. Each year the force of spring 'fought a tug of war' with the force of maturity, creating an oscillation over time:

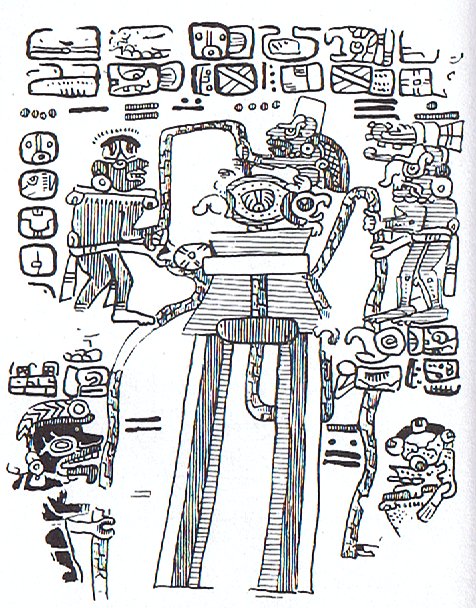

In the rongorongo vocabulary niu represented the beginning of the new (ni-u, Mayan U means Moon), whereas the ariki type of glyph marked the end of the cycle:

The niu type of glyph has the head of the king down in the ground

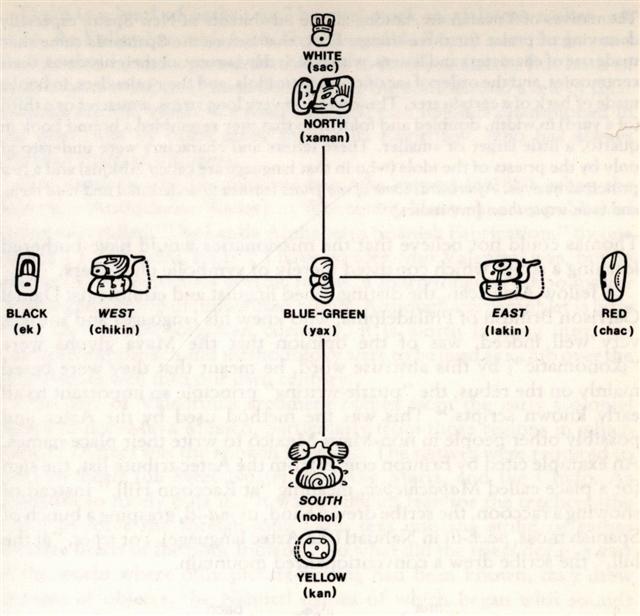

whereas in the ariki type of glyph the head of the king is high up. ... The Inca kingdom was called Tawantinsuyu = 'the indivisible four quarters of the world' and the Inca himself was ruling in its center (Cuzco) ...

There was a Heap of Fuel lying there waiting but the Bright Fire did not occur until day 61, which in rongorongo times was in He Anakena 24 (*125 = 5 * 5 * 5):

The coco would come at the end of the 3rd quarter, where 'the Tree' was short and great sun was at the horizon, descending at the thigh:

... He [Eric Thompson] established that one sign, very common in the [Mayan] codices where it appears affixed to main signs, can be read as 'te' or 'che', 'tree' or 'wood', and as a numerical classifier in counts of periods of time, such as years, months, or days. In Yucatec, you cannot for instance say 'ox haab' for 'three years', but must say 'ox-te haab', 'three-te years'. In modern dictionaries 'te' also means 'tree', and this other meaning for the sign was confirmed when Thompson found it in compounds accompanying pictures of trees in the Dresden Codex. The 4th quarter was ruled by a woman (Moon, U) handling a very long time stick, however without the 'necessary ability' to drill fire. With her sitting posture it would be impossible and her mouth is turned down. In Ga3-5 the sitting figure appears to have generated fire - there are rising maro feathers in front. This was the last day of the month 'He Maro. The last of this kind of 'fire-generating' figures in the G text is at Ga7-10 and at Ga7-13 (182) darkness had fallen over the Land (hatchmarks over te henua):

If my interpretation is correct, then sida a of the tablet is beginning with Sun arriving in spring as viewed from a point north of the equator. With heliacal Antares a change from the northern viewpoint to the southern world should occur, which also appears to be illustrated in Ga7-19 (with fire down below):

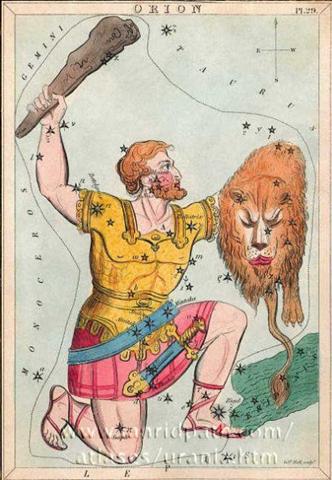

In Ga7-24 we can imagine how the spirit of the dead Old Lion (represented by the swarm of stars π and ο Orionis) has generated a descendant in front.

|