|

A Maori saying: he

iti toki, e rite ana ki te tangata

= though the adze be small, yet does

it equal a man. (Starzecka) |

|

Rite

Hakarite, color, species, class,

mode, equality, condition, manner,

proportion, sort, figure; even,

regular; to align, to assimilate, to

simulate, to compare, to be equal,

to imitate; tae hakarite,

unequal, unfair, inequality,

irregular; hakarite koe,

unequal, unfair, incomparable;

hakarite ke, difference,

diversity, unequal, singular,

variety, extraordinary, fantastic;

e tahi hakarite, thus, so,

as, as much, as many, equal,

uniform, to resemble, to look like;

ariga hakarite, to look like;

niho hakarite, regular teeth.

Hakaritega, comparison,

agreement, parallel, likeness,

similitude. T Ma.: rite,

like. Ha.: like, id. Raro.:

arite, alike, resembling.

Churchill. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Ga1-30 |

Ga2-1 |

Ga2-2 |

Ga2-3 |

Ga2-4 |

|

Furud

(94.9) |

Well-22 |

no star listed (96) |

β Monocerotis, ν Gemini (97.0) |

no star listed (98) |

|

δ Columbae

(95.2),

TEJAT

POSTERIOR,

Mirzam (95.4), CANOPUS (95.6), ε Monocerotis (95.7), ψ1

Aurigae (95.9) |

|

June 23 |

ST JOHN'S

EVE |

25 |

26 (177) |

27 |

|

║June 19 |

20 (*91) |

SOLSTICE |

22 |

23 |

|

'May 27 |

28 (*68) |

29 |

30 (*70) |

31 |

|

'Vaitu Potu 27 |

28 (148) |

29 |

30 (150) |

31 |

|

"May 13 |

14 (*54) |

15

(*55) |

16 (136) |

17 |

|

Purva

Ashadha-20 |

Kaus

Borealis (279.3) |

ν Pavonis

(280.4), κ Cor. Austr. (280.9) |

Abhijit-22 |

|

KAUS

MEDIUS, κ Lyrae (277.5), Tung Hae (277.7) |

KAUS

AUSTRALIS (278.3), ξ Pavonis (278.4), Al Athfar

(278.6) |

θ Cor.

Austr. (281.0),

VEGA (281.8) |

|

December 23

(357) |

CHRISTMAS

EVE |

25 |

26 (360) |

27 |

|

║Dec 19

(*273) |

20 |

SOLSTICE |

22 |

23 (357) |

|

'Novembe 26

(*250) |

27 |

28 |

29 |

30 (*254) |

|

'Ko Ruti 26 |

27 |

28 |

29 (333) |

30 |

|

"Novembe 12

(*236) |

13 |

14 |

15 |

16 (320) |

|

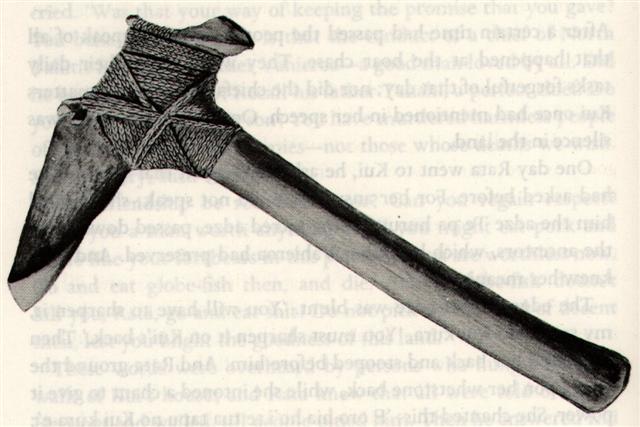

Toki

Small basalt axe. Vanaga.

Stone adze. Van Tilburg.

Ha'amoe ra'a toki =

'Put the adze to sleep' (i.e. hide it in the

temple during the night). Barthel.

Month of the ancient

Rapanui calendar. Fedorova according to

Fischer.

To'i. T. Stone adze

(e to'i purepure = with the

wounderful adze). Henry.

The Araukan Indians in the

coastal area of northern Chile, have customs

similar to those on the Marquesas and in

both areas toki means adze according

to JosÚ Imbelloni. The Araukans also called

their chief of war toki and the

ceremonial adze symbolized his function and

was exhibited at the outbreak of war. In

Polynesia Toki was the name of a

chief elevated by the Gods and his sign was

the blade of a toki. Fraser.

Axe, stone hatchet, stone

tool ...; maea toki, hard slates,

black, red, and gray, used for axes T. P

Pau.: toki, to strike, the edge of

tools, an iron hatchet. Mgv.: toki,

an adze. Mq.: toki, axe, hatchet.

Ta.: toi, axe. Churchill. |

|

The

pan-Polynesian elbow adze, with its variety

of tanged and rectangular stone blades, is

the cornerstone of Polynesian culture and

yet the most controversial of the culture

traits. H. O. Beyer was the first to note in

1948 that tanged and rectangular adz blades

similar to those of Polynesia were known in

very early archaeological periods in the

northern Philippines, but nowhere else in

Indonesia. He shows, however, that these

tanged adz types were used in that area

between 1750 and 1250 B.C. The problem again

arises as to how they could have reached

Polynesia. R. Duff in various lectures has

extended this distribution back to

continental Southeast Asia, but this brings

us no nearer to Polynesia.

Tanged adzes

are unknown throughout Melanesia, where the

blade cross section is even uniformly

cylindrical. Heine-Geldern, looking in vain

for a local passage, admits that the tanged

and rectangular adz could not have passed

that way because of 'the radical difference

in Polynesian and Melanesian blade forms'.

Buck, likewise looking in vain for a

passage, concluded that the Polynesian adz

forms could not have passed the Micronesian

way for the simple reason that no stone

existed on those atolls, thus the

Micronesians were obliged to make their

cutting tools from shell. He pointed out

that the Polynesian adz forms could not have

derived from Southeast Asia at all since the

lack of raw material in the 4,000-mile-wide

Micronesian area created a vast gap, forcing

the Polynesians to invent their own adz

forms independently upon reaching their

volcanic islands in the East Pacific.

We have seen

... however, that there is another and fully

feasible sea route from Southeast Asia to

Polynesia, the only one found possible by

early European sailing ships. This route

entirely avoids the Micronesian-Melanesian

buffer territory and travels from the

Philippine Sea with the Japan Current and

westerly winds to the island-studded coast

of Nortwest America, where all the elements

turn around and bear directly down upon

Hawaii. Once we substitute this northern

island area for Mirconesia or Melanesia as

roadside stations for Asiatic voyagers to

the East Pacific, we immediately find

steppingstones also for the tanged

rectangular adz: it was the principal tool

of the local Nortwest-Coast Indians right up

to the arrival of Europeans. Captain Cook

was the first to point out that the people

of the Northwest American Coast used adzes

similar to those of Tahiti and other

Polynesian islands, and Captain Dixon, after

Cook, noted that the adz of these coastal

Indians 'was a toe made of jasper,

the same as those used by the New

Zealanders'. Captain A. Jacobsen stressed:

'Also the adz-handle and the method of

securing the blade to the wooden handle are

exactly the same among the Polynesian people

as among the Northwest Indians.

Twentieth-century anthropologists have

confirmed these early observations. W. H.

Holmes emphasized that the tanged

rectangular adzes of the Northwest Coast

Indians resemble the adzes of the Pacific

islands more closely than they do the

corresponding tools of other American

tribes, and R. L. Olson wrote in his study

of the Northwest Coast elbow-adz: 'Its

occurence in Polynesia in a form almost

indentical with the elbow adz of America

suggests a hoary age and extra-American

origin'. It is accordingly possible that the

tanged, rectangular adz, belonging only to a

very early period in Asia and the northern

Philippines, spread to Polynesia during a

much later period, following the natural sea

passage by way of Northwest America. (Thor

Heyerdahl, Early Man and the Ocean.) |

|