The volcanoes on Easter Island were dormant. Yet land was shrinking anyhow: ... This island was once a great land. The reason it became so small is because Uoke lifted the earth with a (mighty) pole and then let it sink (into the sea). It was because of the very bad people of Te Pito O Te Henua that Uoke lifted the land (and let it crumble) until it became very small. From the uplifted Te Pito O Te Henua, (they) came to the landing site of Nga Tavake, to Te Ohiro. In Rotomea (near Mataveri) they disembarked and climbed up to stay at Vai Marama (a waterplace near Mataveri). During the next month, they moved on to Te Vare (on the slope of the crater Rano Kau). When they saw that the (land-) lifting Uoke also approached (their present) island, Nga Tavake spoke to Te Ohiro: 'The land is sinking into the sea and we are lost!' But Te Ohiro warded off the danger with a magic chant. In Puku Puhipuhi, Uoke's pole broke, and, in this way, at least Nga Tavake's landing site remained (of the formerly great land). And the Mayas had a sinking 'canoe' in their night sky:

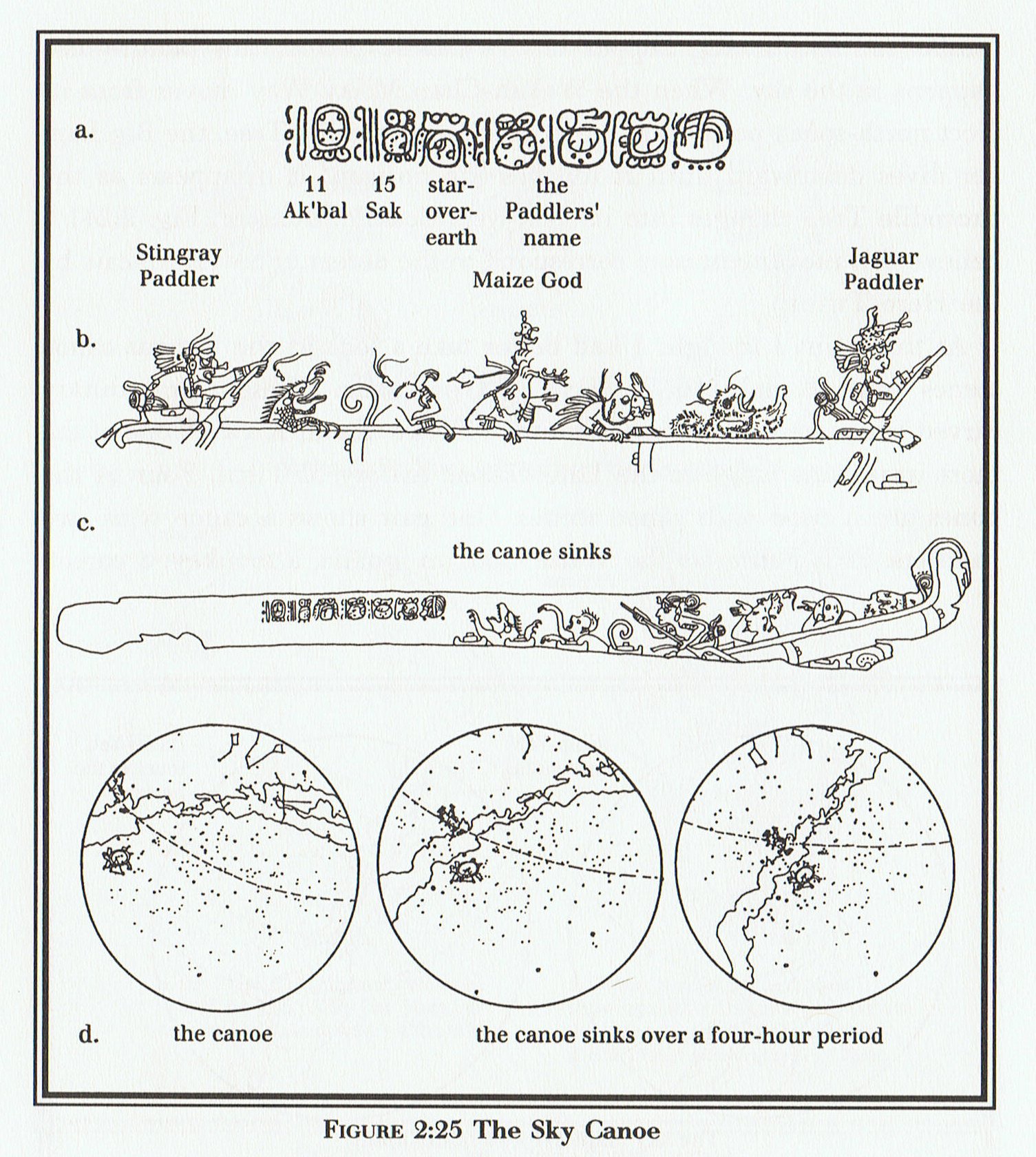

"At midnight the Milky Way was stretched across the sky from east to west in the form of the Cosmic Monster ... It suddenly occurred to me that this configuration could also be the canoe, and that during the four hours after midnight the Cosmic Monster canoe 'sinks' as the Milky Way turns and brings the three hearth stones of Orion to the zenith just before dawn." (David Freidel, Linda Schele, Joy Parker: Maya Cosmos. Three Thousand Years on the Shaman's Path.) A canoe - or at least its midsection (honua) - is floating on the waters like a piece of land, a little land for the life (cfr Moku Ola). ... 4 March 1779. The British ships are again at Kaua'i, their last days in the islands, some thirteen months since their initial visit. A number of Hawaiian men come on board and under the direction of their women, who remain alongside in the canoes, the men deposit navel cords of newborn children in cracks of the ships' decks (Beaglehole 1967:1225). For an analogous behavior observed by the missionary Fison on the Polynesian island of Rotuma, see Frazer (1911, 1:184). Hawaiians are connected to ancestors (auumakua), as well as to living kinsmen and descendants, by several cords emanating from various parts of the body but alike called piko, 'umbilical cord'. In this connection, Mrs. Pukui discusses the incident at Kaua'i: I have seen many old people with small containers for the umbilical cords... One grandmother took the cords of her four grandchildren and dropped them into Alenuihaha channel. 'I want my granddaughters to travel across the sea!' she told me. Mrs. Pukui believes that the story of women hiding their babies' pikos in Captain Cook's ship is probably true. Cook was first thought to be the god Lono, and his ship his 'floating island'. What woman wouldn't want her baby's piko there? Remarkably we have just discussed heliacal Achird at 'March 4 (to be compared with 4 March 1779), and the broken form of henua in Ca1-10 could well illustrate a 'broken canoe awash in the surf' (a dead chief). Cook had to return to the Hawaiian islands because his mast had broken - like the pole of Uoke.

Cook was (as Caesar) a mythic figure: "Cook's first visit, to Kaua'i Island in January 1778, fell within the traditional months of the New Year rites (Makahiki). He returned to the Islands late in the same year, very near the recommencement of the Makahiki ceremonies. Arriving now off northern Maui, Cook proceeded to make a grand circumnavigation of Hawai'i Island in the prescribed clockwise direction of Lono's yearly procession, to land at the temple in Kealaekua Bay where Lono begins and ends his own circuit. The British captain took his leave in early February 1779, almost precisely on the day the Makahiki ceremonies close. But on his way out to Kahiki, the Resolution sprung a mast, and Cook committed the ritual fault of returning unexpectedly and unintelligibly. The Great Navigator was now hors catégorie, a dangerous condition as Leach and Douglas have taught us, and within a few days he was really dead - though certain priests of Lono did afterward ask when he would come back." (Marshall Sahlins, Islands of History.) The transition from one year to the next was, I think, alluded to in the story of Kuukuu (in the Polynesian languages it was not possible to end a word with a consonant). "With the elimination of Kuukuu, Makoi achieves superior status among the sons of Hua Tava: the last-born now holds the rank of the first-born. Through the meeting with Nga Tavake, the representative of the original population in the area north of Rano Kau, the number of the explorers is once again complete. Not only are Kuukuu and Nga Tavake related as 'loss' and 'gain', but also they share the same economic function: it was Kuukuu's special mission to establish a yam plantation after the landing (in this role he represents the vital function of the good planter); Nga Tavake joined the explorers to work with them in the yam plantation of the dead Kuukuu (i.e., he closes the gap caused by the death of Kuukuu among the planters)." (The Eighth Island)

The 3 'stones' standing in the water outside the southwestern corner of Easter Island may have been regarded as the 3 species of tropic birds: ... Ms. A states that Te Taanga ... charged his three sons (Nga Tavake, Te Ohiro, and Hau) with the construction of a canoe. On the other hand we know that the three sons of Te Taanga were turned into the three islets off the southwestern cape of Easter Island and thus served as a landmark for all newcomers, including the dream soul of Hau Maka! Thus, the three sons of Te Taanga, who were lost during the exploratory journey, must belong to an earlier generation. Yet, only 2 of them were mentioned on the island proper:

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||