We now can look closer at the intriguing Ca1-6, which should have some meaning connected with the 'Deluge' depicted in Cb14-17:

The star β Tucanae (6.4) could give us some clues:

... The Chinese translated the original word, given to them by the Jesuits, as Neaou Chuy, the Beak Bird, very appropriate to a creature that is almost all beak ... A beak is normally a hard and pointed instrument in front, suitable for poking holes. Manu tara has such a pointed beak. Another name for the 'sooty tern' is 'sea swallow', a more fitting name because when manu tara returned to Easter Island it was a sign of winter 'going away' (oho). In other words, the manu tara bird 'swallowed' the winter in a way which makes us remember how a 'big Fish' swallowed Jonah. However. the Toucan's magnificent beak is different and we should rather compare with that of manu rere and also with how the beak of a Raven is constructed.

A crooked beak could be the correct instrument at the end of summer, a pointed beak at its beginning:

... He turned round and round to the right as he fell from the sky back to the water. Still in his cradle, he floated on the sea. Then he bumped against something solid. 'Your illustrious grandfather asks you in', said a voice. The Raven saw nothing. He heard the same voice again, and then again, but still he saw nothing but water. Then he peered through the hole in his marten-skin blanket ... Anciently spring may have been described as a time when the 'black cloth' had to be pierced, creating a hole for light to return:

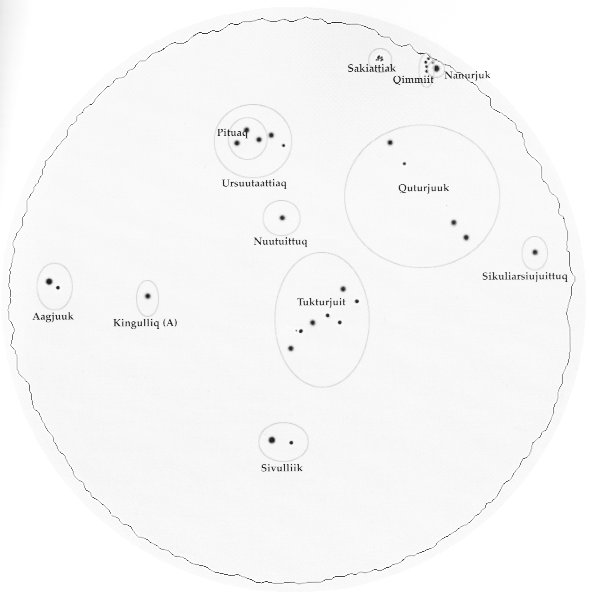

A pair of mata are here connected with the front top corner of the piece of cloth held high. Probably ancient tradition had it that the beginning of the season of light should be announced by a pair of stars (e.g. Al Sharatain): ... Etalook refers to the 'aagruuk' as 'labrets' (the circular lower-lip ornaments of some Western Arctic Eskimo groups, certainly evoke an astral image if we recall that early Inuit gaphic representations of stars were usually circular ...) giving them, it seems, an alternate name, ayaqhaagnailak, 'they prohibit the playing of string games': They are the ones that discourage playing a string game... That's what they're called, ayaqhaagnailak, those two stars... When the two stars come out where is no daylight, people are advised not to play a string game then, but with hii, hii, hii... toy noisemakers of wood or bone and braided sinew ... ... While the stars Altair and Tarazed can be seen during the fall months, late in the evening to the southwest, they are only recognized as Aagjuuk by Inuit following their first morning appearance on the north-eastern horizon, usually around mid-December. Throughout January, February, and March they are seen during the pre-dawn hours but thereafter are rapidly taken over by sunlight as the days lengthen. ... By all accounts, Aagjuuk was for Inuit everywhere one of the most important constellations. It seems to have been known by this name, or a variant of it, across the entire Arctic. ... The linking of Aagjuuk's stars with dawn and solstice were the characteristic feature of this constellation recognized as well by other Arctic peoples, in particular the Chukchis: 'The stars Altair and Tarazed of the constellation Aquila are singled out by the Chukchis as a special constellation, Peggittyn. This constellation is considered to bring the light of the new year, since it appears on the horizon, just at the time of winter solstice. ... The meaning of the term Aagjuuk is not clear. Etymologically, Fortescue has postulated a link between the aayģuk and the Yup´ik term for arrow, 'as if the dual of aayģu, arrow ... ... An emphatic and, in our context, attractive explanation of the constellation's name is found in a legend from Noatak, Alaska. Here agruks (Aagjuuk) are said to be 'the two sunbeams of light cast by the sun when it first reappears above the horizon in late December' ... The legend ... then goes on to recount how these two sunbeams were transformed into stars and so confirms, from the Inuit point of view, the various and widespread connections between the Aagjuuk stars, winter solstice, daylight, and the return of the Sun. ... Most published descriptions of Aagjuuk tend to leave the impression that it suddenly appears on cue as if out of nowhere... This definition is somewhat misleading because throughout the autumn and winter months at latitudes above the Arctic Circle Aagjuuk's principal star, Altair, is one of the brightest and most visible stars in the south and western sectors of the sky. But so completely is Aagjuuk identified with mid-December and the winter solstice that one Igloolik elder, invited to point to the constellation in early November, firmly replied that we would not see it until around Christmas, and this in spite of the fact that Altair was at the time in full view to the southwest.

|