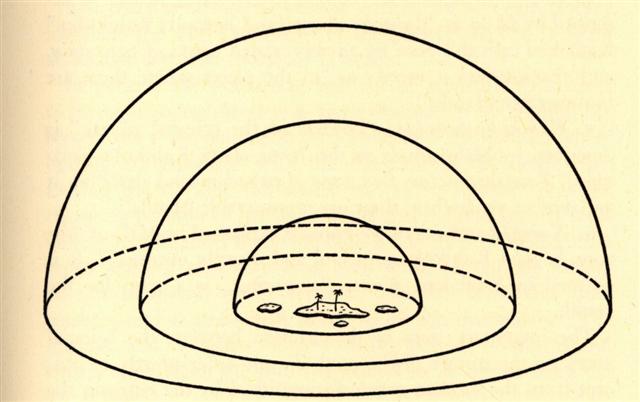

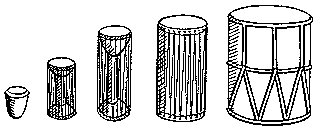

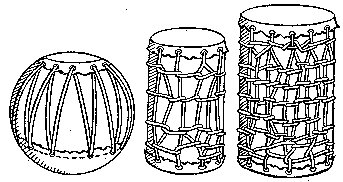

... 'Each drum had a sound of its own, and so each family had its own language, which is the reason why there are different languages today. The first two families, settled in the south, spoke two dialects of Toro, not very different from each other; the third family spoke Mendéli; the fourth spoke Sanga; the fifth another form of Toro; the sixth Bamba; and the seventh Iréli. Lastly the eighth family was given a language which is understood in all parts of the cliff. Just as the eighth drum dominates all the others, so the eighth language is understood everywhere. It was thus that men were given the third Word, final, complete and multiform to suit the new age. It was closely associated, like the first and second Words, and even more than they, with material objects.' At this point an odd reflection occurred to the European. The first imperfect Word was associated with a technical process, simple in character and no doubt the most archaic of all processes, which had produced the most primitive form of clothing made of fibre. The fibre, which was neither knotted nor woven, flowed in a wavy line, and might be said therefore to be of one dimension. The second Word, less restricted than the first, arose from weaving, done on a wide warp crossed by vertical threads forming a surface, that is to say, having two dimensions. The third Word, clear and perfect in character, took shape in a cylinder with a strip of copper winding through it, that is to say, in a three-dimensional figure. These three technical processes (as he further remarked) all proceeded by following a line, either undulating or zig-zag, and each was characterized by three distinct features: humidity of the fibres, ensuring the freshness necessary for procreation; light for the weaving, that being a daylight process, prohibited at night on pain of blindness; sonority of the drum. There was also a development, from the material point of view, from trimmed bark to cotton thread, and from thread to leather strips and to a copper band. The European had known for years the magical function of the sounds of a smithy. He had been present many times at rituals in the course of which at a certain point a smith would strike the rock with his hammer or with the iron part of his anvil. By producing sound from the iron, in which the mythical first smith had brought so many benefits to mankind, he was reminding his fellow-men of the supreme power of Amma and the Water Spirit. He was assisting their prayers and strengthening them by the sounds he made; he was appeasing the possible wrath of the celestial Beings by this acknowledgement of their pre-eminence. When men quarrelled with one another, he would intervene between the parties, hammer in hand, and strike the rocks, thus bringing a divine note into the human disorder and calming the passions aroused ... The most important of all drums, he said, was the armpit drum. The Nummo made it. It consists of two hemispherical wooden cups connected through their centres by a slender cylinder. It is like an hour-glass with a very long narrow neck. With this instrument tucked between his left arm and armpit, the drummer, by pressing on the hollow structure of thin wood, can tighten or relax the tension on the skins and so modify the tone. 'The Nummo made it. He made a picture of it with his fingers, as children do today in games with string.' Holding his hands apart, he passed a thread ten times round each of the four fingers, but not the thumb. He thus had forty loops on each hand, making eighty threads in all, which, he pointed out, was also the number of teeth of his jaws. The palms of his hands represented the skins of the drum, and thus to play on the drum was, symbolically, to play on the hands of the Nummo. But what do they represent? Cupping his two hands behind his ears, Ogotemmêli explained that the spirit had no external ears but only auditory holes. 'His hands serve for ears,' he said; 'to enable him to hear he always holds them on each side of his head. To tap the drum is to tap the Nummo's palms, to tap, that is, his ears.' Holding before him the web of threads which represented a weft, the Spirit with his tongue interlaced them with a kind of endless chain made of a thin strip of copper. He coiled this in a spiral of eighty turns, and throughout the process he spoke as he had done when teaching the art of weaving. But what he said was new. It was the third Word, which he was revealing to men ... |