I guess the pair of

'sleeping' (moe) 'lizards' (moko)

264-265 days from the beginning of side b

could represent twice 184 = 368 days:

|

January 1 |

2 |

3 (368) |

|

July 2 |

3 (184) |

4 |

|

|

|

|

Cb11-8 (260) |

Cb11-9 |

Cb11-10 (654) |

|

vai o ako hia |

te

manu |

tere te marama |

|

λ Pavonis (285.7),

Ain al Rami (286.2),

δ Lyrae (286.3), κ

Pavonis (286.5) |

Alya (286.6), ξ

Sagittarii (287.1),

ω Pavonis (287.3),

ε Aquilae, ε

Cor. Austr.,

Sulaphat (287.4) |

Uttara Ashadha-21 |

|

λ Lyrae (287.7),

Ascella,

Bered (Ant.) (287.9),

NUNKI

(288.4), ζ Cor.

Austr. (288.5) |

|

ψ8 Aurigae (103.2) |

Alhena (103.8), ψ9

Aurigae |

Adara (104.8), ω

Gemini (105.4) |

|

January 4 |

5 |

6 |

|

July

5 |

6 |

7 (188) |

|

|

|

|

Cb11-11 |

Cb11-12 (264) |

Cb11-13 (657) |

|

te

ariki |

te

moko ariga moe |

moko

moe |

|

19h

(289.2) |

Al Baldah-19 |

Aladfar (291.1), Nodus

II (291.5) |

|

Manubrium

(288.8),

ζ Aquilae

(288.9),

λ Aquilae (Ant.)

(289.1), γ Cor.

Austr. (289.3), τ

Sagittarii (289.4),

ι Lyrae (289.5) |

δ Cor. Austr. (289.8),

AL BALDAH,

Alphekka Meridiana

(290.1), β Cor. Austr.

(290.2) |

|

7h (106.5) |

Wezen (107.1) |

δ Monocerotis (107.9) |

|

Alzirr (105.7),

Muliphein (105.8) |

Although these

exhausted twin moko

differ much from their 2 * 11 more

lively precursors in the text

they are of the same 'species',

for instance with bulging

stomachs.

A change occurs

in Gregorian day 372, when - we

can imagine - 'a

little light' (illustrated by

henua signs in poor

condition) enters between the

two 'shells':

|

January 7 (372) |

8 |

|

9 |

|

July 8 |

9 (190) |

10 |

|

|

|

|

Cb11-14

(658) |

Cb11-15 |

Cb11-16 (268) |

|

tagata

ka tomo i roto -

i tona

mea |

tona

mea |

kua kake te tagata

-

ki tona rona |

|

ψ Sagittarii (291.6), θ

Lyrae (291.8),

ω Aquilae

(292.1) |

ρ Sagittarii (292.6), υ

Sagittarii (292.7),

Arkab Prior (293.0),

Arkab Posterior, Alrami

(293.2) |

χ Sagittarii (293.6),

Deneb Okab

(294.0) |

|

no star listed |

Wasat (109.8) |

Aludra (111.1) |

Metoro

distinguished between the first

two irregular henua

shapes and the 3rd such, naming

them tona mea

respectively tona rona.

Perhaps his distinction

reflected the difference between

how tona

mea had 'straight' bottom

ends, whereas tona rona

had concave short ends both at

top and bottom. (Earlier I have

guessed that a straight bottom

end in a henua glyph

represented the line of the

horizon.)

Mea (memea)

is here probably meant as the

colour of dawn:

|

Mea

1.

Tonsil, gill (of

fish). 2. Red

(probably because it

is the colour of

gills); light red,

rose; also meamea.

3. To grow or to

exist in abundance

in a place or around

a place: ku-mea-á

te maîka,

bananas grow in

abundance (in this

place); ku-mea-á

te ka, there is

plenty of fish (in a

stretch of the coast

or the sea);

ku-mea-á te tai,

the tide is low and

the sea completely

calm (good for

fishing); mau

mea, abundance.

Vanaga.

1.

Red;

ata mea,

the dawn.

Meamea,

red, ruddy,

rubricund, scarlet,

vermilion, yellow;

ariga meamea,

florid;

kahu meamea

purple;

moni meamea,

gold;

hanuanua meamea,

rainbow;

pua ei meamea,

to make yellow.

Hakameamea,

to redden, to make

yellow. PS Ta.:

mea,

red. Sa.:

memea,

yellowish brown,

sere. To.:

memea,

drab. Fu.:

mea,

blond, yellowish,

red, chestnut. 2. A

thing, an object,

elements (mee);

e mea,

circumstance;

mea ke,

differently,

excepted, save, but;

ra mea,

to belong;

mea rakerake,

assault;

ko mea,

such a one;

a mea nei,

this;

a mea ka,

during;

a mea,

then;

no te mea,

because, since,

seeing that;

na te mea,

since;

a mea era,

that;

ko mea tera,

however, but.

Hakamea,

to prepare, to make

ready. P Pau., Mgv.,

Mq., Ta.:

mea, a

thing. 3. In order

that, for. Mgv.:

mea,

because, on account

of, seeing that,

since. Mq.:

mea,

for. 4. An

individual;

tagata mea,

tagata mee,

an individual. Mgv.:

mea,

an individual, such

a one. Mq., Ta.:

mea,

such a one. 5.

Necessary, urgent;

e mea ka,

must needs be,

necessary;

e mea,

urgent. 6. Manners,

customs. 7. Mgv.:

ako-mea,

a red fish. 8. Ta.:

mea,

to do. Mq.:

mea,

id. Sa.:

mea,

id. Mao.:

mea,

id. Churchill. |

|

... After this

separation

Rangi

lamented for his

wife: and his

tears are the

dew and the rain

which ever fall

on her. This was

the chant that

did the work:

Rangitokona,

prop up the

heaven! //

Rangitokona,

prop up the

morning! // The

pillar stands in

the empty space.

The thought [memea]

stands in the

earth-world - //

Thought stands

also in the sky.

The kahi

stands in the

earth-world - //

Kahi

stands also in

the sky.

The pillar

stands, the

pillar - // It

ever stands, the

pillar of the

sky.

Then for the

first time was

there light

between the Sky

and the Earth;

the world

existed ... |

Next stage

ought to be when Sun is ascending

(kake) - although in

early morning the light

will still be poor and the

shadows will still be ruling.

The 'break of dawn' (the early

days in the year) may have been

a dangerous time:

|

Rona

Figure made of

wood, or stone,

or painted,

representing a

bird, a birdman,

a lizard, etc.

Vanaga.

Drawing,

traction. Pau.:

ronarona,

to pull one

another about.

Churchill.

While the

rongorongo signs

(rona)

are generally

'carved out,

incised' (motu),

ta

implies an

incision

('cutting,

beating') as

well as the

process of

applying signs

to the surface

with the aid of

a dye ...

Barthel 2. |

|

"After naming

the

topographical

features of

Easter Island

with names from

their land of

origin, the

emissaries went

from the west

coast up to the

rim of the

crater Rano

Kau, where

Kuukuu

had started a

yam plantation

some time

earlier.

After they had

departed from

Pu Pakakina

they reached

Vai Marama

and met a man.

Ira

asked, 'How many

are you?'

He answered,

'There are two

of us.' Ira

continued

asking, 'Where

is he (the

other)?'

To that he

answered, 'The

one died.' Again

Ira

asked, 'Who has

died?'

He replied,

'That was Te

Ohiro A Te Runu.'

Ira asked

anew, 'And who

are your?'

He answered, 'Nga

Tavake A Te Rona.'

(E:46)

After this, the

emissaries and

Nga Tavake

went to the yam

plantation."

(Barthel 2) |

|

"... RAP.

rona means

primarily 'sign'

(an individual

sign in the

Rongorongo

script or a

painted or

carved sign made

on a firm

background, such

as a

petroglyph), but

also 'sculpture'

(made from wood

or stone,

representing

animals of

hybrid

creatures) ...

... rona

(lona)

implies the idea

of 'maintaining

a straight line'

with ropes and

nets and also

the maintaining

of a steady

course (in MAO.

and TUA.).

Te Rona

is the name of a

star in TUA.,

which Makemson

(1941:251)

derives from the

mythical figure

of 'Rona',

who is connected

with the moon

and is

considered to be

the father of

(the moon

goddess) Hina

(for this role

in MAO., see

Tregear

1891:423).

From west

Polynesia come

totally

different

meanings.

Interesting

perhaps is FIJ.

lona, 'to

wonder what one

is to eat,

fasting for the

dead.' ..."

(Barthel 2) |

To avoid this

type of danger the ruling king

might have installed a 'mock

king' north of the equator and a

pair of such kings south of the

equator. The 'sleeping' Lono

figure on Hawaii 'played the

role of sacrifice', was

dismembered and then tucked away

for another year. Towards the

end of the midwinter ceremonies

a tribute-canoe with offerings

to Lono 'was set adrift

for Kahiki, homeland of

the gods':

... in the ceremonial course of

the coming year, the king is

symbolically transposed toward

the Lono pole of Hawaiian

divinity ... It need only be

noticed that the renewal of

kingship at the climax of the

Makahiki coincides with the

rebirth of nature. For in the

ideal ritual calendar, the

kali'i battle follows the

autumnal appearance of the

Pleiades, by thirty-three days -

thus precisely, in the late

eighteenth century, 21 December,

the winter solstice. The king

returns to power with the sun.

Whereas, over the next two days,

Lono plays the part of

the sacrifice. The Makahiki

effigy is dismantled and hidden

away in a rite watched over by

the king's 'living god',

Kahoali'i or

'The-Companion-of-the-King', the

one who is also known as

'Death-is-Near' (Koke-na-make).

Close kinsman of the king as his

ceremonial double, Kahoali'i

swallows the eye of the victim

in ceremonies of human sacrifice

...

The 'living god', moreover,

passes the night prior to the

dismemberment of Lono in

a temporary house called 'the

net house of Kahoali'i',

set up before the temple

structure where the image

sleeps. In the myth pertinent to

these rites, the trickster hero

- whose father has the same name

(Kuuka'ohi'alaki) as the

Kuu-image of the temple -

uses a certain 'net of

Maoloha' to encircle a

house, entrapping the goddess

Haumea; whereas, Haumea

(or Papa) is also a

version of La'ila'i, the

archetypal fertile woman, and

the net used to entangle her had

belonged to one Makali'i,

'Pleiades'.

Just so, the succeeding

Makahiki ceremony, following

upon the putting away of the

god, is called 'the net of

Maoloha', and represents the

gains in fertility accruing to

the people from the victory over

Lono. A large,

loose-mesh net, filled with all

kinds of food, is shaken at a

priest's command. Fallen to

earth, and to man's lot, the

food is the augury of the coming

year. The fertility of nature

thus taken by humanity, a

tribute-canoe of offerings to

Lono is set adrift for

Kahiki, homeland of the

gods. The New Year draws to a

close. At the next full moon, a

man (a tabu transgressor) will

be caught by Kahoali'i

and sacrificed. Soon after the

houses and standing images of

the temple will be rebuilt:

consecrated - with more human

sacrifices - to the rites of

Kuu and the projects of the

king.

On Easter Island

the hare paega dwellings had a pair

of rona (manu uru

figures) guarding the entrances:

"The low entrances of houses

were guarded by images of wood

or of bark cloth, representing

lizards or rarely crayfish.

The bark cloth images were made

over frames of reed, and were

called manu-uru, a name

given also to kites, masks, and

masked people

..."

(Alfred Métraux, Ethnology of

Easter Island.)

Below are a few

of all my comments

regarding rona in my

preliminary glyph type

dictionary:

|

... The

lizard (moko)

and the crayfish (ura)

form a pair of

contrasts, one up on

land and the other

down in the sea.

Manu-uru

are not real

'birds', just

imitations

(reflections) made

of 'straw'.

Metoro

said toa

tauuru

for 7 of the periods

of the night (cfr

Aa1-37--46).

In my added item for

uru in the

Polynesian

dictionary I have

commented that

uru usually

means breadfruit (=

'skull') and that

its fruit resembles

a human skull. A

cranium and uru

symbolize, I think,

the end of life -

which has great

nutritional value.

Uru has 2

u, as is should

for a 'back wheel'.

Nightfall and

morning connect the

diurnal cycle with

the yearly cycle.

The hour of midnight

was preferably a

time for sleep,

because at that time

(equal to new year)

there was a 'door'

open through which

figures of fancy and

fear moved.

Métraux has given us

a good description

of how it was to

sleep in a hare

paega:

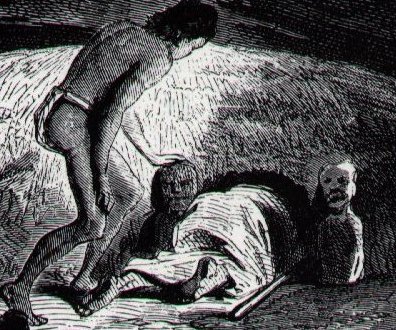

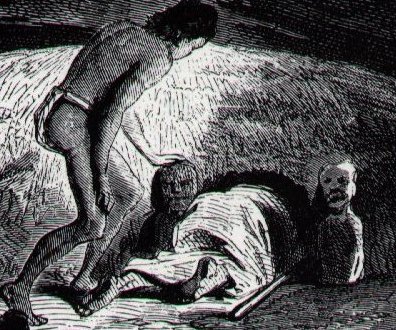

'... The most vivid

description of hut

interiors is given

by Eyraud ... who

slept in them

several nights:

Imagine a half open

mussel, resting on

the edge of its

valves and you will

have an idea of the

form of that cabin.

Some sticks covered

with straw form its

frame and roof. An

oven-like opening

allows its

inhabitants to go

inside as well as

the visitors who

have to creep not

only on all fours

but on their

stomachs.

This indicates the

center of the

building and lets

enter enough light

to see when you have

been inside for a

while. You have no

idea how many Kanacs

may find shelter

under that thatch

roof. It is rather

hot inside, if you

make abstraction of

the little

disagreements caused

by the deficient

cleanliness of the

natives and the

community of goods

which inevitably

introduces itself

...

But by night time,

when you do not find

other refuge, you

are forced to do as

others do. Then

everybody takes his

place, the position

being indicated to

each by the nature

of the spot. The

door, being in the

center, determines

an axis which

divides the hut into

two equal parts. The

heads, facing each

other on each side

of that axis, allow

enough room between

them to let pass

those who enter or

go out. So they lie

breadthwise, as

commodiously as

possible, and try to

sleep.'

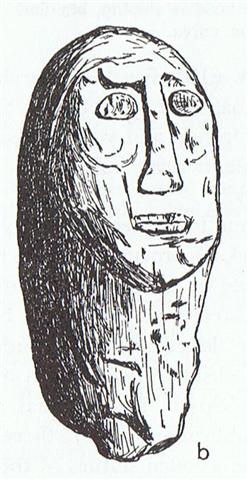

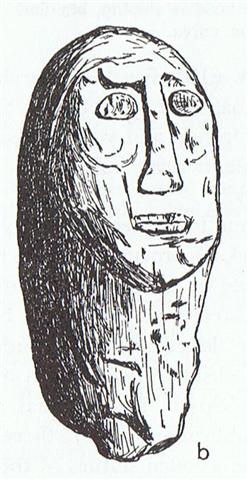

Métraux has also

given us a close-up

picture of one of

these manu-uru

figures:

'The nose is narrow

and straight and on

the same plane as

the forehead. The

mouth is formed by

two parallel raised

strips. The oval

eyes protrude. The

cheekbones are two

crescentic

prominences

...' |

|