It is now time to begin to

discuss the elusive Rei type of

glyph:

|

Alrescha 1 |

2 |

3 |

4

(354) |

|

May 2 |

3 |

4 |

5 (125) |

|

|

|

|

|

Ca2-16 |

Ca2-17 |

Ca2-18 |

Ca2-19 (45) |

|

erua

tamaiti |

ki

te huaga o te hoi hatu |

e

tagata poo pouo |

| |

|

Menkar

(44.7) |

|

Alrescha

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

|

May 6 |

7 (492) |

8 (128) |

9 |

|

|

|

|

|

Ca2-20 |

Ca2-21 |

Ca2-22

(48) |

Ca2-23 |

| te vai |

e tino noho toona |

te Rei

- pa hia mai |

kiore i te

henua |

|

3h

(45.7) |

|

|

|

|

Rei

1. To tread,

to trample on: rei kiraro

ki te va'e. 2. (Used

figuratively) away with you!

ka-rei kiraro koe, e

mageo ê, go away, you

disgusting man. 3. To shed

tears: he rei i te mata

vai. 4. Crescent-shaped

breast ornament, necklace;

reimiro, wooden,

crescent-shaped breast

ornament; rei matapuku,

necklace made of coral

or of mother-of-pearl;

rei pipipipi, necklace

made of shells; rei

pureva, necklace made of

stones. 5. Clavicle.

Îka

reirei,

vanquished

enemy, who is kicked (rei).

Vanaga.

T. 1.

Neck. 2. Figure-head.

Rei mua =

Figure-head in the bow.

Rei muri =

Figure-head in the stern.

Henry.

Mother of

pearl;

rei kauaha, fin.

Mgv.:

rei, whale's

tooth. Mq.:

éi, id. This is

probably associable with the

general Polynesian

rei, which means

the tooth of the cachalot,

an object held in such

esteem that in Viti one

tooth (tambua)

was the ransom of a man's

life, the ransom of a soul

on the spirit path that led

through the perils of Na

Kauvandra to the last abode

in Mbulotu. The word is

undoubtedly descriptive,

generic as to some character

which Polynesian perception

sees shared by whale ivory

and nacre.

Rei kauaha is not

this

rei; in the Maori

whakarei

designates the carved work

at bow and stern of the

canoe and Tahiti has the

same use but without

particularizing the carving:

assuming a sense descriptive

of something which projects

in a relatively thin and

flat form from the main

body, and this describes

these canoe ornaments, it

will be seen that it might

be applied to the fins of

fishes, which in these

waters are frequently

ornamental in hue and shape.

The latter sense is confined

to the Tongafiti migration.

Reirei,

to trample down, to knead,

to pound. Churchill.

Pau.:

Rei-hopehopega, nape.

Churchill.

Mg.

Reiga, Spirit

leaping-place. Oral

Traditions. |

A rei miro

(wooden pendant) should hang

around the neck (rei) of its

owner as a

sign of who is chief ('officer

on duty').

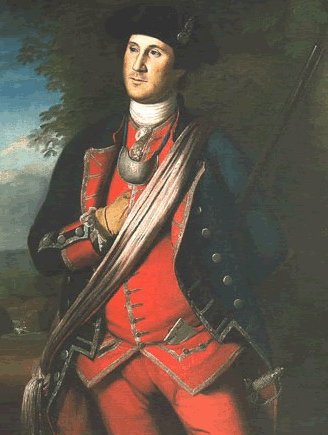

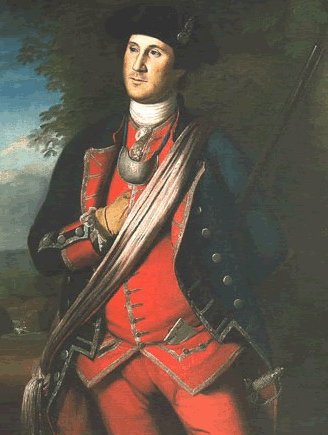

"Throughout

Polynesia, the word rei

signifies a neck ornament of

some kind, perhaps

internationally best known as

Hawaii's lei ('flower

necklace'). Easter Island's

rei miro ('wooden rei')

are without parallel in

Polynesia. However, they display

a form that is strikingly

similar to the silver crescent

gorget worn by Cook's Marine

Officer Gibson who accompanied

Cook on all three voyages,

including the one to Rapa Nui

in 1774. Such silver crescent

gorgets was prescribed dress for

a Marine Officer of the British

Royal Navy in the second half of

the eighteenth century. Rapa

Nui's rei miro were attested

only after 1774." (Fischer)

This is how silver gorgets look like:

"... A

gorget

originally

was a

steel

collar

designed

to

protect

the

throat.

It was a

feature

of older

types of

armour

and

intended

to

protect

against

swords

and

other

non-projectile

weapons.

Later,

particularly

from the

18th

century

onwards,

the

gorget

became

primarily

ornamental,

serving

only as

a

symbolic

accessory

on

military

uniforms.

Most

Medieval

versions

of

gorgets

were

simple

neck

protectors

that

were

worn

under

the

breastplate

and

backplate

set.

These

neck

plates

supported

the

weight

of the

armour

worn

over it,

and many

were

equipped

with

straps

for

attaching

the

heavier

armour

plates.

Later,

Renaissance

gorgets

were not

worn

with a

breastplate

but

instead

were

worn

over the

clothing.

Most

gorgets

of this

period

were

beautifully

etched,

gilt,

engraved,

chased,

embossed,

or

enamelled

and

probably

very

expensive.

Gorgets

were the

last

form of

armour

worn on

the

battlefield.

During

the 18th

and

early

19th

centuries,

crescent-shaped

gorgets

of

silver

or

silver

gilt

were

worn by

officers

in most

European

armies,

both as

a badge

of rank

and an

indication

that

they

were on

duty.

These

last

survivals

of

armour

were

much

smaller

(usually

about

three to

four

inches

in

width)

than

their

Medieval

predecessors

and were

suspended

by

chains

or

ribbons.

In the

British

service

they

carried

the

Royal

coat of

arms

until

1796 and

thereafter

the

Royal

cypher.

Colonel

George

Washington

wore a

gorget

as part

of his

uniform

in the

French

and

Indian

War,

which

symbolized

his

commission

as an

officer

in the

Virginia

Regiment.

Gorgets

ceased

to be

worn by

British

army

officers

in 1830,

and by

their

French

counterparts

20 years

later

..."

(Wikipedia)

|

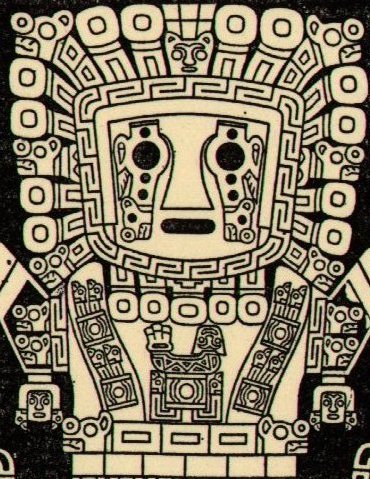

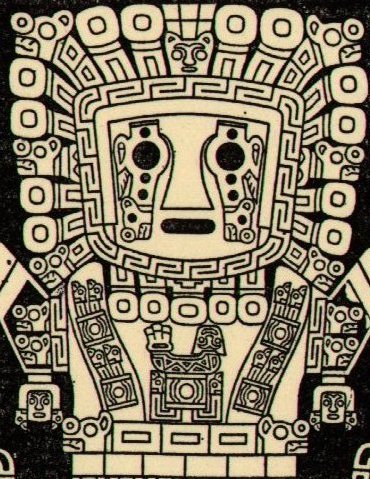

But these gorgets

cannot explain the rei miro

wooden 'silvery fishes' altogether,

because the idea was there already,

as we can see from Tiahuanaco, where

the central person wears a fish on

his honourable chest:

I think this cup-formed fish represents the winter season, when Moon

(a woman often thought of as a fish) was ruling, when Sun

was on the other side of the equator, when the manu rere

spirit of Sun was not present, and when the migrating birds were

far away. Instead of the season of 'birds' (= high up and

high sky) it was the season of 'fishes' (= far

down and low sky). Our rule of double negatives can be

used to ascertain the probable meaning of re.

It should be the opposite of rere (moving quickly and

full of life energy). My suggestion can be tried when

searching for the meaning of the 'sprit leaping' places, rei-ga. These

places are for people whose life energies have been completely exhausted.

They need

to be 'refueled' high up in the sky, where warmth and life

is originating. My reasoning leads to

the conclusion that the first part in the word Re-i could refer to a

position close to the horizon, in the southwest (toga)

or below the horizon in the east.

Some support for my suggestion of the meaning of

re is given by re-ga (the place, -ga, of re),

because rega (ginger) was the Easter Island variant of

the kava root:

|

Rega

Ancient word,

apparently meaning 'pretty,

beautiful'. It seems to have

been used also to mean 'girl'

judging from the nicknames given

young women: rega hopu-hopu.

girl fond of bathing;

rega maruaki, hungry girl;

rega úraúra,

crimson-faced girl. Vanaga.

Pau.: rega,

ginger. Mgv.: rega,

turmeric. Ta.: rea, id.

Mq.: ena, id. Sa.:

lega, id. Ma.: renga,

pollen of bulrushes. Churchill. |

| "The impact of

lightning and thunder -

as if there was a pair of gods 'talking' to our eyes

and ears - apparently makes nature wake up. A change

of state mostly follows with fresh air and sun

returning. The kava

glyph type is designed as a zigzag pattern, much

like that written in lightning on the dark stormy

sky. Lightning and thunder work magic together

creating sunligth and rain. Sunlight and rain are

related ...

One of the effects of kava

drinking is to enhance the sensitivity of the eyes -

light appears to be growing ..." (From my

preliminary glyph type dictionary.) |

The

place of beauty (rega) should be early in spring, when

winter is subdued:

|

Re

Pau.: victory.

Ta.: re,

prize in any contest, prey. Mgv.:

Re-mai,

to emerge from prison, to recover from illness,

delivered from evil. Mq.:

ee,

to go, to escape. Sa.: lele,

to go out (of the passing soul). Ha.:

lele,

to depart (of the spirit). Churchill. |

When in

spring Sun returns (hoki) with vai ('sweet

water') to the cultivated fields (hatu) the result is

growth - new food, best illustrated as a hand eating (kai). This

hand is the opposite of the Mayan Chikin (grasping) hand.

When the Sun king (the 'trunk', te tino, of the

community) is present

the land where

he resides (noho) will become fertile again. I will

here take the opportunity to define a new type of glyph,

perhaps close to

but opposite in meaning to raaraa (marae,

'no Sun'):

|

|

|

tino |

raaraa |

... The people

(mahingo) listened as he spoke. The king called out

to his guardian spirits (akuaku), Kuihi and

Kuaha, in a loud voice: 'Let the voice of the rooster of

Ariana crow softly. The stem with many roots (i.e.,

the king) is entering!' The king fell down, and Hotu A

Matua died. Then all the people began to lament with

loud voices. The royal child, Tuu Maheke, picked up

the litter and lifted (the dead) unto it. Tuu Maheke

put his hand to the right side of the litter, and together

the four children of Matua picked up the litter and

carried it ...

... What I saw

stunned me, for in her hand lay a perfect replica of the

earflares worn by the Classic Maya kings. Suddenly I

understood the full symbolism of so many of the things I had

been studying for years. The kings dressed themselves as the

Wakah-Chan tree, although at the time I didn't know

it was also the Milky Way.

The tzuk [partition] head on the trunk of the tree

covered their loins. The branches with their white flowers

bent down along their thighs, the double-headed ecliptic

snake rested in their arms, and the great bird Itzam-Yeh

stood on their head. I already knew as I stood under the

young tree in Tikal that the kings were the human embodiment

of the ceiba as the central axis of the world. As I stood

there gazing at the flowers in Joyce's hand, I also learned

that the kings embodied the ceiba at the moment it flowers

to yield the sak-nik-nal, the 'white flowers', that

are the souls of human beings. As the trees flowers to

reproduce itself, so the kings flowered to reproduce the

world ...

|