2. The synodical period of Jupiter is 399 days and we have therefore earlier located him at glyph number 399. In the chapter Te Pito I suggested a connection between Gb6-16 (where 61 * 6 = 366) and months counted as 31 days:

In Eye in the Mud I tried to find correlations between number 378 and the glyphs in the G text:

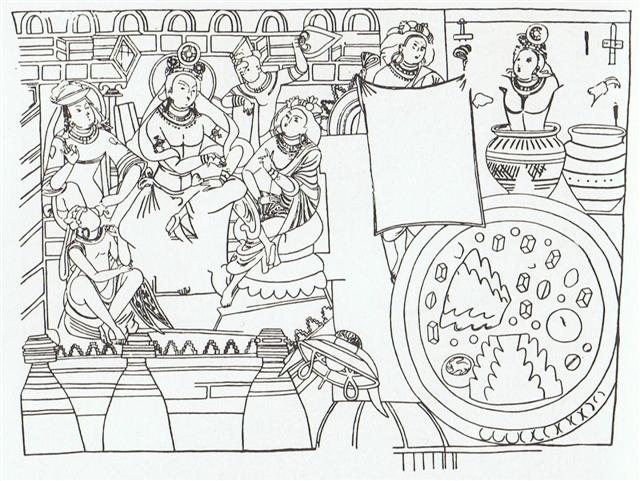

It is remarkable that the sidereal period of Saturn is close to 29½ years, a fact which ought to have made the ancient minds connect it with the 29½ synodical nights of Moon. Hakaariki (to make a king) in Gb5-24 is glyph number 378, which seems fitting because Saturn is the one who will create a new 'fire' (Sun king). And 5 * 24 = 120 = ⅓ of 360. I am aware that in this a case I am using another counting method than my 'rule of thumb'. However, 52 * 4 = 208 (= 13 * 16) is not ruled out, which could mean that both the cycle of Sun and the cycle of Moon are finished here. Furthermore, 5 is the symbol for fire and 24 are the number of hours in a day (like the number of hours for a complete right ascension cycle). In the illustration below there are 5 people at left (under the 8 'cap' signs) and the central figure surely must be Sun himself, fire personified:

⅔ of the picture (at left) is used for the season when Sun is present and ⅓ (at right) for the time of his absence. The pair to the right of Sun are higher located than the pair at the left. It probably means high summer is defined by the 'tree trunk' - with a quarter of the Sun face at its top - below the 8th of the cap signs. In the Kuukuu chapter I presented the sacred 5-stone cosmogram (the quincunx) and how the sky roof was uplifted by the 4 supporters: ... On February 9 the Chorti Ah K'in, 'diviners', begin the agricultural year. Both the 260-day cycle and the solar year are used in setting dates for religious and agricultural ceremonies, especially when those rituals fall at the same time in both calendars. The ceremony begins when the diviners go to a sacred spring where they choose five stones with the proper shape and color. These stones will mark the five positions of the sacred cosmogram created by the ritual. When the stones are brought back to the ceremonial house, two diviners start the ritual by placing the stones on a table in a careful pattern that reproduces the schematic of the universe. At the same time, helpers under the table replace last year's diagram with the new one. They believe that by placing the cosmic diagram under the base of God at the center of the world they demonstrate that God dominates the universe. The priests place the stones in a very particular order. First the stone that corresponds to the sun in the eastern, sunrise position of summer solstice is set down; then the stone corresponding to the western, sunset position of the same solstice. This is followed by stones representing the western, sunset position of the winter solstice, then its eastern, sunrise position. Together these four stones form a square. They sit at the four corners of the square just as we saw in the Creation story from the Classic period and in the Popol Vuh. Finally, the center stone is placed to form the ancient five-point sign modern researchers called the quincunx ... Later on in this series of rituals, the Chorti go through a ceremony they call raising the sky. This ritual takes place at midnight on the twenty-fifth of April and continues each night until the rains arrive. In this ceremony two diviners and their wives sit on benches so that they occupy the corner positions of the cosmic square. They take their seats in the same order as the stones were placed, with the men on the eastern side and the women on the west. The ritual actions of sitting down and lifting upward are done with great precision and care, because they are directly related to the actions done by the gods at Creation. The people represent the gods of the four corners and the clouds that cover the earth. As they rise from their seats, they metaphorically lift the sky. If their lifting motion is uneven, the rains will be irregular and harmful ... In Hanga Takaure I continued my argumentation: ... The 5th stone, the center stone, is drawn in the middle of the square form of the quincunx, and an example is offered by kan, the Mayan glyph for yellow:

I guess the corresponding rongorongo sign is vai (fresh sweet rain water):

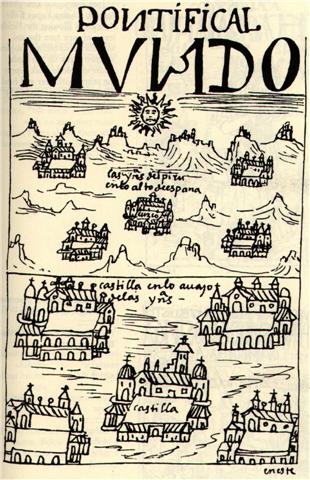

When the precious rain is falling from the sky the vai sign can be changed into the sign of vaha kai, because the 4 diviners (supporters of the sky roof) are no longer needed. In other words, at the beginning of land (when the sky roof is raised high by the 4 supporters) the sweet water is gradually accumulating in the sky (from the evaporation of small water puddles down on earth), and at this time of the year the Mayan quincunx glyph shows 4 corner stones as sky proppers with Sun shining in the center. Then his Rain God time has come and Sun lets go of all these waters, creating a situation of flood down on earth, and the sky proppers are no longer needed. The sign changes to vaha kai. If my suggestion is correct, then we can anticipate a reversal when we compare the domain of the sky with what happens down in our own region. When the sweet water is above in the sky it cannot be down below and contrariwise ... In Peru the conception was the same, the ruling Sun king was in the center surrounding by 4 supporters:

This illustration is from Ronald Wright, Cut Stones and Crossroads. A Journey in the Two Worlds of Peru. The 'pontificial world' (Pontifical Mundo) has Peru at the top and Spain at bottom, in both cases with the central edifices occupying the place of the Sun. Wright explains: [This is] Waman Puma's conception of the relationship between Peru and Spain according to the Andean duality principle of Hanan (Upper) and Hurin (Lower). Each country is showns as a Tawantinsuyu - four quarters with a capital in the center. Peru is higher, closer to the sun, and therefore full of gold, the 'sweat of the sun'. In Wikipedia one can read: "... Guaman Poma appeared as a plaintiff in a series of lawsuits from the late 1590s, in which he attempted to recover land and political title in the Chupas valley that he believed to be his by family right. These suits ultimately proved disastrous for him; not only did he lose the suits, but in 1600 he was stripped of all his property and forced into exile from the towns which he had once ruled as a noble ..." |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||