Once again. In the Mayan calendar for the year we can find a contrast between the open mouth of Zotz and the closed mouth of Moan (and we should remember to read the pictures from right to left, i.e. neither of them was looking back in time, neither of them carried a sign of reversal):

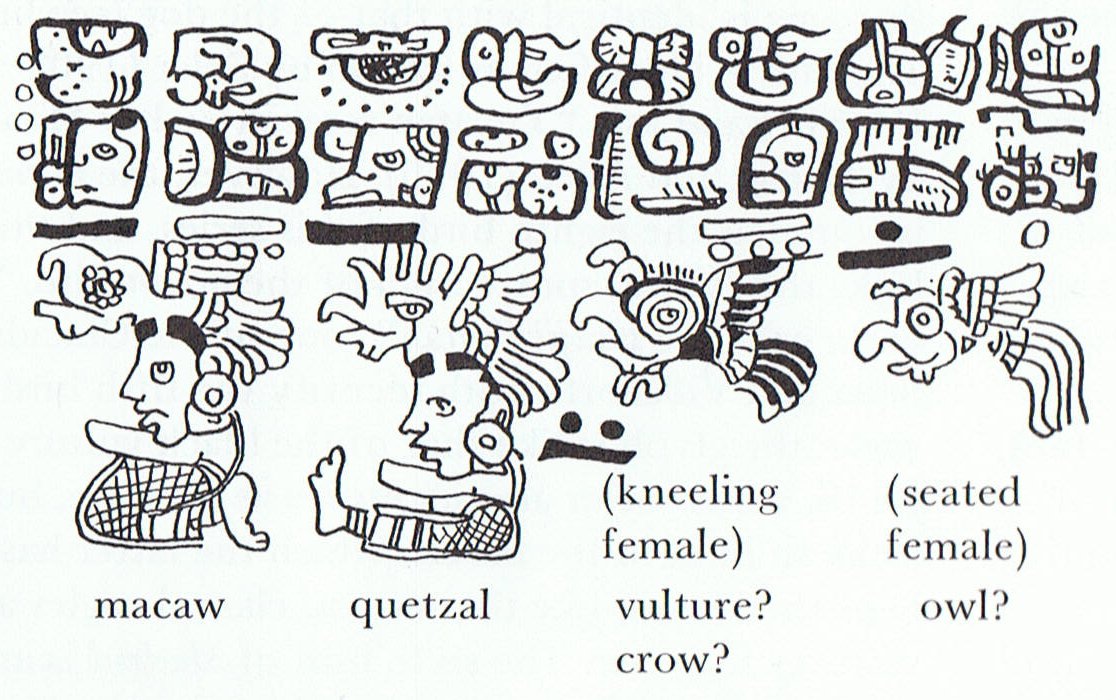

The Moan bird could be an owl (a type of bird which avoids daylight): ... The third bird in Madrid is identified as a king vulture by Tozzer and Allen (1910) and as a crow by Villacorta (Villacorta and Villacorta 1930). Seler (1909, IV, 556) has also identified this bird as a vulture.

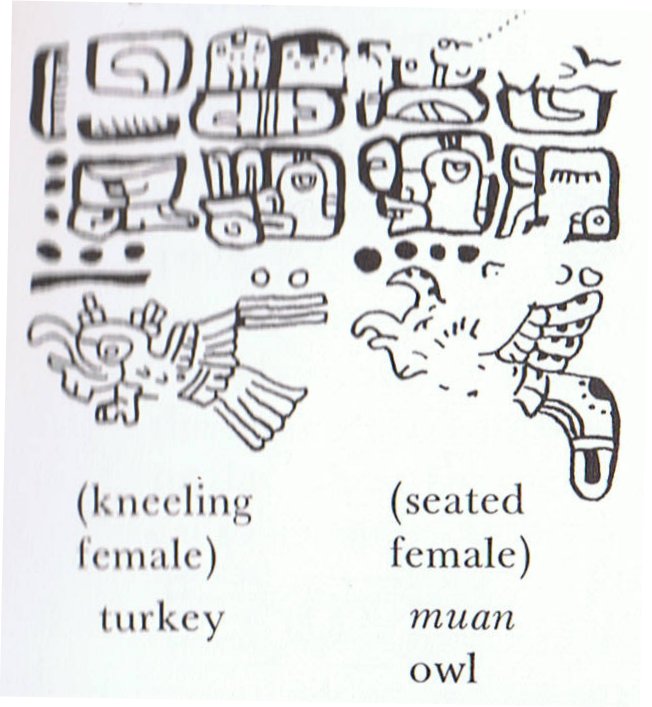

However, the probable identifying glyph looks like yax. Quiche raxon (from *yax-) is 'blue dove', or a gray bird with blue wings. The fourth bird is very interesting, as the glyger which should correspond to its name is identical with that of the dog (see below). The bird is identified as an owl by Seeler (1902-1923, IV, 612) and as a 'Yucatan screech owl or Moan-bird' by Tozzer and Allen (1910). However, the muan bird is found as the eighth bird of this series, and this bird lacks the typical spotted tail of the muan bird. Villacorta calls it a paujil ('guan'), one of the Cracidae. Seler and Villacorta both identify the fifth bird as an eagle; the glyph is like that of the black vulture of D17b, which Seler also identifies as an eagle, but it lacks an infix in the mouth which the latter has. Perhaps the Mayas, like the Aztecs, classed eagles and vultures together. The sixth bird of Madrid is an owl, identified by Seler as the muan bird, but by Tozzer and Allen as an icim owl. The first glyger above is apparently that of the owl, although Bartel thinks the second glyph [the one at top right] is that of the owl. He draws attention to the use of this glyger in connection with the muan owls of D7c and D10a (personal communication), but I believe that the true glyph of the muan owl proper in these cases is one which might be read 'Thirteen Heaven' - it is worth noting that the number thirteen is prefixed to the muan bird's head as part of its glyph on D16c.The first glyger in Madrid begins with Landa's i.

The seventh bird is a turkey, but the name glyph, if present, is completely different from the one in Dresden or elsewhere in Madrid.

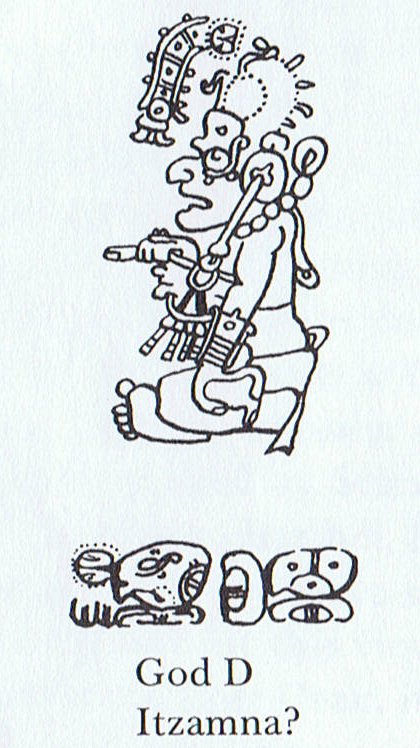

The final bird is the muan owl, here called only by a title that was normally applied to God D ..." (David Humiston Kelley, Deciphering the Maya Script.) These 6 birds (gods) could evidently have begun after high summer, after Mol and the Well (Ch'en):

The first of them was Macaw:

... Men and birds joined forces to destroy the huge watersnake, which dragged all living creatures down to his lair. But the attackers took fright and cried off, one after the other, offering as their excuse that they could only fight on dry land. Finally, the duckler (K.G.: a diver) was brave enough to dive into the water; he inflicted a fatal wound on the monster which was at the bottom, coiled round the roots of an enormous tree. Uttering terrible cries, the men succeeded in bringing the snake out of the water, where they killed it and removed its skin. The duckler claimed the skin as the price of its victory. The Indian chiefs said ironically, 'By all means! Just take it away!' 'With pleasure', replied the duckler as it signalled to the other birds. Together they swooped down and, each one taking a piece of the skin in its beak, flew off with it. The Indians were annoyed and angry and, from then on, became the enemies of birds. The birds retired to a quiet spot in order to share the skin. They agreed that each one should keep the part that was in its own beak. The skin was made up of marvelous colors - red, yellow, green, black, and white - and had markings such as no one had ever seen before. As soon as each bird was provided with the part to which it was entitled, the miracle happened: until that time all birds had had dingy plumage, but now suddenly they became white, yellow, and blue ... The parrots were covered in green and red, and the macaws with red, purple, and gilded feathers, such as had never before been seen. The duckler, to which all the credit was due, was left with the head, which was black. But it said it was good enough for an old bird ... ... The white egret took its piece [of the skin of 'Keyemen - the rainbow in the shape of a huge watersnake'] and sang, 'ā-ā', a call that it still has to this day. The maguari (Circonia maguari, a stork) did likewise and uttered its ugly cry: 'a(o)-a(o)'. The soco (Ardea brasiliensis, a heron) placed its piece on its head and wings (where the colored feathers are) and sang, 'koro-koro-koro'. The kingfisher (Alcedo species) put its piece on its head and breast, where the feathers turned red, and sang, 'se-txe-txe-txe'. Then it was the toucan's turn. It covered its breast and belly (where the feathers are white and red). And it said: 'kión-he, he kión-he'. A small piece of skin remained stuck to its beak which became yellow. Then came the mutum (Crax species); it put is piece on its throat and sang, 'hm-hm-hm-hm' and a tiny remaining strip of skin turned its nostrils yellow. Next came the cujubin (Pipile species, a piping guan), whose piece turned its head, breast, and wings white: it sang, 'krr' as it has done every morning since. Each bird 'thought its own flute made a pretty sound and kept it.' (Claude Lévi-Strauss, The Raw and the Cooked. Introduction to a Science of Mythology: 1.)

Why use up precious energy by piling up apparently irrelevant information like this? Because once upon a time there was a common cosmos and without access to this rich source very little will be understood. ... and then, with stunning abruptness, at a crucial date that can be almost precisely fixed at 3200 BC (in the period of the archaeological stratum known as Uruk B), there appears in this little Sumerian mud garden - as though the flowers of its tiny cities were suddenly bursting into bloom - the whole cultural syndrome that has since constituted the germinal unit of all the high civilization of the world. And we cannot attribute this event to any achievement of the mentality of simple peasants. Nor was it the mechanical consequence of a simple piling up of material artifacts, economically determined. It was actually and clearly the highly conscious creation (this much can be asserted with complete assurance) of the mind and science of a new order of humanity, which had never before appeared in the history of mankind; namely, the professional, full-time, initiated, strictly regimented temple priest. The new inspiration of civilized life was based, first, on the discovery, through long and meticulous, carefully checked and rechecked observations, that there were, besides the sun and moon, five other visible or barely visible heavenly spheres (to wit, Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn) which moved in established courses, according to established laws, along the ways followed by the sun and moon, among the fixed stars; and then, second, on the almost insane, playful, yet potentially terrible notion that the laws governing the movements of the seven heavenly spheres should in some mystical way be the same as those governing the life and thought of men on earth. The whole city, not simply the temple area, was now conceived as an imitation on earth of the cosmic order, a sociological 'middle cosmos', or mesocosm, established by priestcraft between the macrocosm of the universe and the microcosm of the individual, making visible the one essential form of all. The king was the center, as a human representative of the power made celestially manifest either in the sun or the moon, according to the focus of the local cult; the walled city was organized architecturally in the design of a quartered circle (like the circles designed on the ceramic ware of the period just preceeding), centered around the pivotal sanctum of the palace or ziggurat (as the ceramic designs around the cross, rosette, or swastika); and there was a mathematically structured calendar to regulate the seasons of the city's life according to the passages of the sun and moon among the stars - as well as a highly developed system of liturgical arts, including music, the art rendering audible to human ears the world-ordering harmony of the celestial spheres. It was at this moment in human destiny that the art of writing first appeared in the world and that scriptorially documented history therefore begins. Also, the wheel appeared. And we have evidence of the development of the two numerical systems still normally employed throughout the civilized world, the decimal and the sexigesimal; the former was used mostly for business accounts in the offices of the temple compounds, where the grain was stored that had been collected as taxes, and the latter for the ritualistic measuring of space and time as well. Three hundred and sixty degrees, then as now, represented the circumference of a circle - the cycle of the horizon - while three hundred and sixty days, plus five, marked the measurement of the circle of the year, the cycle of time. The five intercalated days that bring the total to three hundred and sixty-five were taken to represent a sacred opening through which spiritual energy flowed into the round of the temporal universe from the pleroma of eternity, and they were designated, consequently, days of holy feast and festival. Comparably, the ziggurat, the pivotal point in the center of the sacred circle of space, where the earthly and heavenly powers joined, was also characterized by the number five; for the four sides of the tower, oriented to the points of the compass, came together at the summit, the fifth point, and it was there that the energy of heaven met the earth. The early Sumerian temple tower with the hieratically organized little city surrounding it, where everyone played his role according to the rules of a celestially inspired divine game, supplied the model of paradise that we find, centuries later, in the Hindu-Buddhist imagery of the world mountain, Sumeru, whose jeweled slopes, facing the four directions, peopled on the west by sacred serpents, on the south by gnomes, on the north by earth giants, and on the east by divine musicians, rose from the mid-point of the earth as the vertical axis of the egg-shaped universe, and bore on its quadrangular summit the palatial mansions of the deathless gods, whose towered city was known as Amaravati, 'The Town Immortal'. But it was the model also of the Greek Olympus, the Aztec temples of the sun, and Dante's holy mountain of Purgatory, bearing on its summit the Earthly Paradise. For the form and concept of the City of God conceived as a 'mesochosm' (an earthly imitation of the celestial order of the macrocosm) which emerged on the threshold of history circa 3200 BC, at precisely that geographical point where the rivers of Tigris and Euphrates reach the Persian Gulf, was disseminated eastward and westward along the ways already blazed by the earlier neolithic. The wonderful life-organizing assemblage of ideas and principles - including those of kingship, writing, mathematics, and calendrical astronomy - reached the Nile, circa 2800 BC; it spread to Crete on the one hand, and on the other, to the valley of the Indus, circa 2600 BC; to Shang China, circa 1600 BC; and, according to at least one high authority, Dr Robert Heine-Geldern, from China across the Pacific, during the prosperous seafaring period of the late Chou Dynasty, between the seventh and fourth centuries BC, to Peru and Middle America ... (Joseph Campbell, The Masks of God: Primitive Mythology.)

'Twinkle, twinkle, little bat!' // How I wonder what you're at!' |