Once again:

... The water dots invite us to count, and one of several possible structures is:

46 + 91 = 137, which could point at May 17 (137). But the last of the water dots is special and we should probably instead count 46 + 90 = 136 (May 16), when at the time of rongorongo and according to the Gregorian calendar Alcyone rose with the Sun.

Beyond Alcyone came the rain (te ua) and Porrima culminated at midnight:

We can perceive the gap in Cb2-6 as an illustration of the gap here forced upon between the upside down sky bowl (right) and the world below - receiving the benefits of rain and beams from the Sun. South of the equator November was a spring month corresponding to May in the north. ... The four males and the four females were couples in consequence of their lower, i.e. of their sexual parts. The four males were man and woman, and the four females were woman and man. In the case of the males it was the man, and in the case of the females it was the woman, who played the dominant role. They coupled and became pregnant each in him or herself, and so produced their offspring. But in the fullness of time an obscure instinct led the eldest of them towards the anthill which had been occupied by the Nummo. He wore on his head a head-dress and to protect him from the sun, the wooden bowl he used for his food. He put his two feet into the opening of the anthill, that is of the earth's womb, and sank in slowly as if for a parturition a tergo. The whole of him thus entered into the earth, and his head itself disappeared. But he left on the ground, as evidence of his passage into that world, the bowl which had caught on the edges of the opening. All that remained on the anthill was the round wooden bowl, still bearing traces of the food and the finger-prints of its vanished owner, symbol of his body and of his human nature, as, in the animal world, is the skin which a reptile has shed ... (Marcel Griaule, Conversations with Ogotemmêli.) In essence the central element in Cb2-6 is a tapa mea (red Sun light cloth) type of glyph with 8 'Tree Feathers', 4 of them p.m. ('males') and 4 of them a.m. ('females').

... Ta'aroa sat in his heaven above the earth and conjured forth gods with his words. When he shook off his red and yellow feathers they drifted down and became trees ... The marama (moon) type of glyph at right is not of the normal type, instead it could represent the sky above - reversed like an upside down bowl.

Perhaps we should see Ca12-22 (where 12 * 22 = 264) - 84 glyphs earlier - as the place of origin for this 'upside down sky bowl':

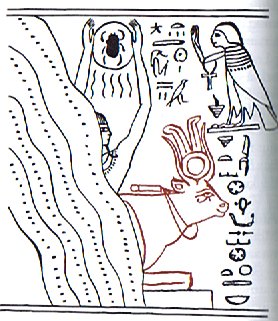

The Egyptian Hathor - the winter House of Horus from which he emerged (was born) in the east, raised high by her arms above the streams of water - could evidently have been a central element in a once upon a time common human cosmography:

... Earlier we have counted the duration of this watery 'mountain' to be 121 nights and therefore possibly ending with l May 1 (121):

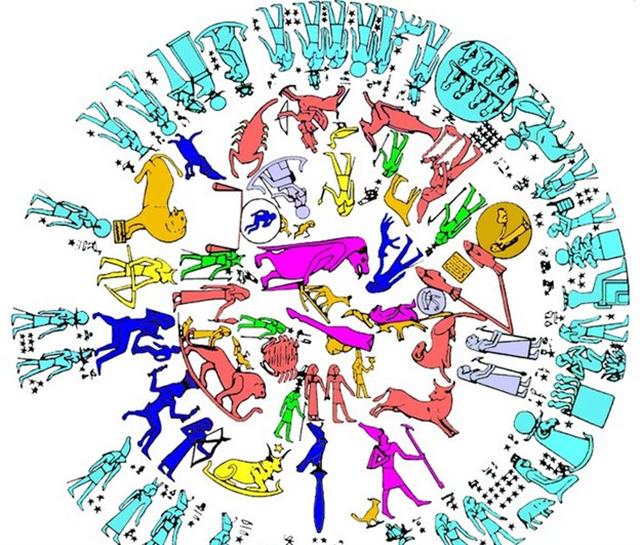

136 - 121 = 15 = the precessional distance up from Alcyone (*56) to Bharani (*41). I.e. they were the same, they both gave birth to the morning Sun, which the round (implying a vertical shaft) Dendera roof explained. ... In the Dendera round zodiac (Egypt, ca 50 B.C.) we can see the little Sun child (Horus) resting on the beam of Libra while sucking his thumb and at the other side of the sky, where we would expect to find Musca Borealis, there is a Wedjat Sun eye ...

... The sky that floats above the earth, // great Rangi nui, the spread-out space, dwelt with the red glow of dawn // and the moon was made; the great sky above us // dwelt with the shooting rays and the sun sprang forth, // they were thrown up above us as the chief eyes of heaven. Then the heavens became light, // the early dawn, the early day, // the mid-day, the blaze of day from sky. Then Rangi nui, the Sky, dwelt with Papa tu a nuku, the Earth, and was joined to her, and land was made. But the offspring of Rangi and Papa, who were very numerous, were not of the shape of men, and they lived in darkness, for their parents were not yet parted. The Sky still lay upon the Earth, no light had come between them. The heavens were ten i number, and the lowest layer, lying on the Earth, made her unfruitful. Her covering was creeping plants and rank low weed, and the sea was all dark water, dark as night. The time when these things were seemed without end, as it is stated in the tradition: From the first division of time unto the tenth, and to the hundredth, and to the thousandth, all was barren, and in vain did she seek her offspring in the likeness of the day, or of the night. At length the offspring of Rangi and Papa, worn out with continual darkness, met together to decide what should be done about their parents, that man might arise. 'Shall we kill our parents, shall we slay them, our father and our mother, or shall we separate them? 'they asked. And long did they consider in the darkness: The night, the night, the day, the day, the seeking out, the adzing out from the nothing, the nothing. Their seeking thought also for their mother, that man might arise. Behold, this is the word, the largeness, the length, the height of their thought. At last Tu matauenga, the fiercest of the offspring of Sky and Earth and the god of war, spoke out. Said Tu: 'It is well. Let us kill them.' But Tane mahuta, god and father of the forests and all things that inhabit them, answered: 'No, not so. It is better to rend them apart, and to let the Sky stand far above us and the Earth lie below here. Let the Sky become a stranger to us, but let Earth remain close to us as our nursing mother.' The other sons, and Tu the war god among them, saw wisdom in this and agreed with Tane, all but one. This one, that now forever disagreed with all his brothers, was the god and father of winds and storms, Tawhiri matea. Tawhiri, fearing that his kingdom would be overthrown, did not wish his parents to be torn apart. So while five sons agreed, Tawhiri was silent and would not [speak], he held his breath. And long did they consider further. At the end of a time no man can measure the five decided that Rangi and Papa must be forced apart, and they began by turns to attempt this deed. First Rongo ma Tane, god and father of the cultivated food of men, rose up and strove to force the heavens from the earth. When Rongo had failed, next Tangaroa, god and father of all things that live in the sea, rose up. He struggled mightily, but had no luck. And next Haumia tiketike, god and father of uncultivated food, rose up and tried without success. So then Tu matauenga, god of war, leapt up. Tu hacked at the sinews that bound the Earth and Sky, and made them bleed, and this gave rise to ochre, or red clay, the sacred colour. Yet even Tu, the fiercest of the sons, could not with all his strength sever Rangi from Papa. So then it became the turn of Tane mahuta. Slowly, slowly as the kauri tree did Tane rise between the Earth and Sky. At first he strove with his arms to move them, but with no success. Then he placed his shoulders against the Earth his mother, and his feet against the Sky. Soon, and yet not soon, for the time was vast, the Sky and Earth began to yield. The sinews that bound them stretched and ripped. With heavy groans and shrieks of pain, the parents of the sons cried out and asked them why they did this crime, why did they wish to slay their parents' love? Great Tane thrust with all his strength, which was the strength of growth. Far beneath him he pressed the Earth. Far above he thrust the Sky, and held them there. As soon as Tane's work was finished the multituide of creatures were uncovered whom Rangi and Papa had begotten, and who had never known light. Now rose up Tawhiri, the god of winds and storms, who all this time had held his breath. Great anger moved him now, and this was Rangi's wish. Tawhiri, who feared that his kingdom would be overthrown, feared also that the Earth would become too fair and beautiful. For he was jealous now, jealous of all that Tane had procured. For Tane was the author of the day - Of the great day, // of the long day, of the clear day, // of the day driving away night, of the day making all things distinct, // of the day making everything bright, of the day driving away gloom, // of the hot, sultry day, of the day shrouded in darkness. And so Tawhiri followed Rangi to the realm above, and consulted with him there. And with his father's help Tawhiri begot his numerous turbulent offspring, the winds and storms. He sent them off between the Sky and the Earth, one to the south, another to the east, another to the north-east. Then, in his anger, and remembering Rangi's wish, he sent the freezing wind, the burning dusty wind, the rainy wind, the sleety wind, and with them all the different kinds of clouds. Most powerful of all, Tawhiri himself came down lika a hurricane, and placed his mouth to that of Tane, and shook his branches and uprooted him. The giant trees of Tane's forests groaned and fell, and lay upon the earth to rot away, and became the food of grubs. When his fury had dealt with Tane, Tawhiri turned on Tangaroa the sea god. From the forests he swept on down to the sea and lashed it in his rage. He heaved up waves as high as cliffs and whipped their crests away, he churned the sea to whirlpools, he battled with the tides, till Tangaroa took flight in terror from his usual home, the shores, and hid in the ocean depths, where Tawhiri could not reach him. As Tangaroa was about to leave the shores, his grand-children consulted together as to how they might save themselves. For Tangaroa had begotten Punga, and Punga had begotten Ika tere, the father of fish, and Tu te wanawana, the father of lizards and reptiles. These two could not agree where it was best to go to escape the storms. Tu te wanawana and his party, shouting into the wind, cried 'Let us all go inland,' but Ika tere and his party cried 'No, let us go to the sea.' Some obeyed one and some the other, and so they escaped in two parties. Those of Tu te wanawana hid themselves on land, and those of Ika tere in the sea. This is what is called, in the ancient traditions of our people, 'The Separation of Tawhiri matea', and it is put in this fable: The Shark was for going to the sea, but the Lizard was for going inland. Shark warned Lizard, 'Go inland, and the fate of your race will be that when they catch you and before they cook you, they will singe your skins off over a lighted wisp of fern.' Lizard answered, 'Go to the sea, and the fate of your race will be that when they serve out baskets of food to each person, you will be laid on top to give a relish to it.' So they fled their separate ways, the fishes in confusion to the sea, and the lizards and reptiles to the little hiding places in the forests and the rocks. And for this reason Tangaroa, enraged that some of his offspring deserted him and were sheltered by the forests, has ever since made war on Tane, who in return has helped those who are at war with Tangaroa. So the sea is forever eating at the edges of the land, hoping that the forest trees will fall and become his food, and he consumes the trees and houses that are carried down to him by floods ...

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||