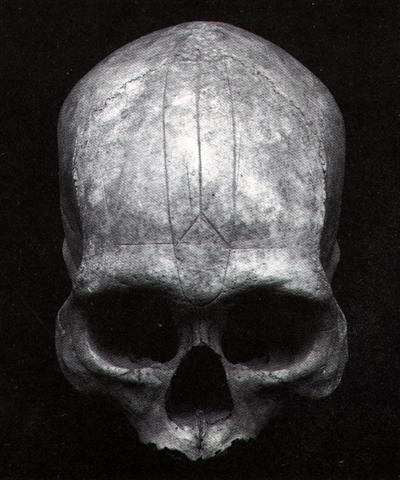

A few preliminary remarks and imaginations: 1. The picture in moa glyphs appear to show a cock - not a hen (moa uha) and not a youngster (moa taga) but a fully grown and potent rooster (moa to'a): "While the dog and the pig existed only in the traditions as the shadows of the past, the domestic fowl (moa) that were brought along achieved a position of supreme importance. As a matter of fact, they dominated the island's economy to the point that one is tempted to speak of a prevailing 'economy of fowl'! Their influence, in its many ramifications, touched every aspect of life of the Easter Islanders, including the socioeconomic and the ideologic. As the only permanent livestock, they were an essential part of the islanders' subsistence. All sources count moa (Gallus sp.) among the animals imported by Hotu Matua, and the terminology, including figurative terms, is solidly rooted in the Polynesian language. Moa means 'fowl' in general as a generic term, but it also means 'rooster'. On the other hand, the name for 'hen' is formed by adding uha, the general Polynesian addition for female animals. Specific names are formed by adding attributes to moa - such as moa maanga and moa rikiriki for 'chicken', moa tanga for 'young hen or rooster', and moa toa for an especially splendid 'rooster'. There is an extensive terminology dealing with characteristics of the anatomy and the different types of plumage. It is also truly amazing to what extent types and scenes from the world of fowl were projected upon people and situations. Some examples of 'zoomorphic patterns of speech' will serve to illustrate the point. An adopted child is a 'chick that is being nourished' (maanga hangai). Formerly, a marriageable daughter, as well as a beloved wife, was called a 'hen' (uha). It was a mark of distinction for a grown son or a brave young man to be referred to as a 'rooster' (moa) ..." (Barthel 2) The virility of a cock was intertwined with that of a chief: "Up to the present time, fertility spells for fowls have played an important role. Especially effective were the so-called 'chicken skulls' (puoko moa) - that is, the skulls of dead chiefs, often marked by incisions, that were considered a source of mana. Their task is explained as follows: 'The skulls of the chiefs are for the chicken, so that thousands may be born' (te puoko ariki mo te moa, mo topa o te piere) ... As long as the source of mana is kept in the house, the hens are impregnated (he rei te moa i te uha), they lay eggs (he ne'ine'i te uha i te mamari), and the chicks are hatched (he topa te maanga). After a period of time, the beneficial skull has to be removed, because otherwise the hens become exhausted from laying eggs." (Barthel 2)

|