Ba10.1 Line Ba9 ends with a glyph which is positioned 390 right ascension days after Hassaleh (*73); 390 - 365 = 25 and *73 + *25 = *98. Possibly *98 together with 9-49 were intended to point out the necessity to count in weeks instead of days. 98 days = 14 weeks and 9 * 49 = 441 = 63 * 7. The last glyph on side b of the G tablet was probably corresponding to right ascension day *63. ... When this tremendous task had been accomplished Atea took a third husband, Fa'a-hotu, Make Fruitful. Then occurred a curious event. Whether Atea had wearied of bringing forth offspring we are not told, but certain it is that Atea and her husband Fa'a-hotu exchanged sexes. Then the [male] eyes of Atea glanced down at those of his wife Hotu and they begat Ru. It was this Ru who explored the whole earth and divided it into north, south, east, and west ...

On the C tablet we can see that Metoro had identified the 'maker of the little one' (tagata hakaititi) at the end of the text. Line Ba10 is beginning with a picture of the Sun (Raa), and the Full Moon should be at the right ascension line leading down from Vega, the star which once upon a time had been at the North Pole.

According to the words of Metoro he probably saw this part of the text as describing the 'opening' (vaha) of a new year. Vaha. Hollow; opening; space between the fingers (vaha rima); door cracks (vaha papare). Vahavaha, to fight, to wrangle, to argue with abusive words. Vanaga. 1. Space, before T; vaha takitua, perineum. PS Mgv.: vaha, a space, an open place. Mq.: vaha, separated, not joined. Ta.: vaha, an opening. Sa.: vasa, space, interval. To.: vaha, vahaa, id. Fu.: vasa, vāsaà, id. Niuē: vahā. 2. Muscle, tendon; vahavaha, id. Vahahora (vaha 1 - hora 2), spring. Vahatoga (vaha 1 - toga 1), autumn. 3. Ta.: vahavaha, to disdain, to dislike. Ha.: wahawaha, to hate, to dislike. Churchill.

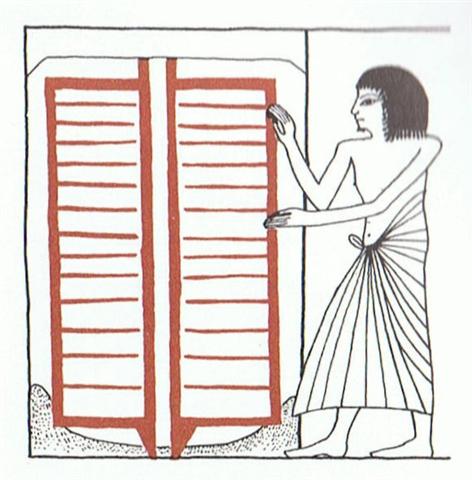

3 days after Vega there is a glyph which might illustrate the pair of holes ('doors'), one for the Sun to enter through at the horizon in the east (mea) and the other one (mea ké) to descend through in the evening (at the horizon in the west).

Here we ought to compare with the contrasting glyph 24 right ascension days earlier:

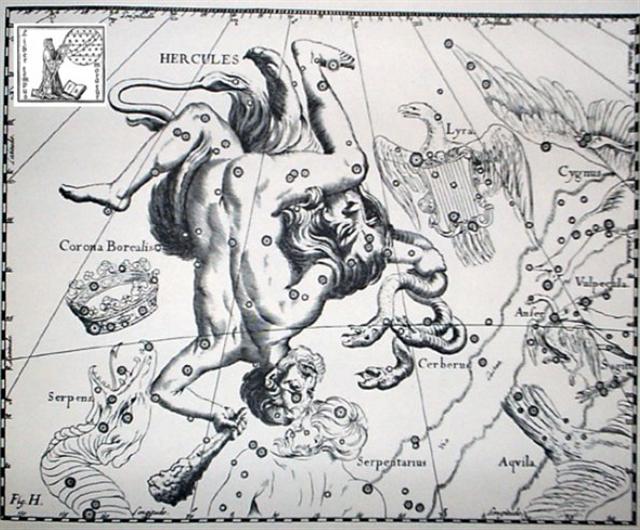

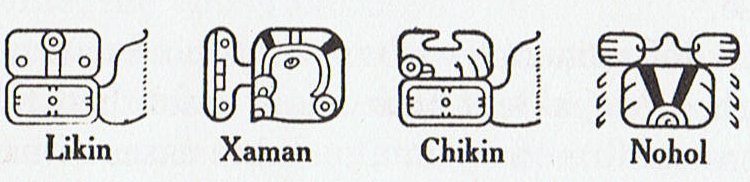

At this time of the year the Head of Hercules had to be illustrated upside down and therefore also his mouth should be drawn upside down (i.e. at left in the rongorongo idiom). At the horizon in the west the Sun was 'swallowed' every evening and therefore also every fall. ... The manik, with the tzab, or serpent's rattles as prefix, runs across Madrid tz. 22 , the figures in the pictures all holding the rattle; it runs across the hunting scenes of Madrid tz. 61, 62, and finally appears in all four clauses of tz. 175, the so-called 'baptism' tzolkin. It seems impossible, with all this, to avoid assigning the value of grasping or receiving. But in the final confirmation, we have the direct evidence of the signs for East and West. For the East we have the glyph Ahau-Kin, the Lord Sun, the Lord of Day; for the West we have Manik-Kin, exactly corresponding to the term Chikin, the biting or eating of the Sun, seizing it in the mouth.

The pictures (from Gates) show east, north, west, and south; respectively (the lower two glyphs) 'Lord' (Ahau) and 'grasp' (Manik). Manik was the 7th day sign of the 20 and Ahau the last ... His 'eye openings' would disappear downwards into the dark side of the night. Probably nighttime was indicated by kaikai strings (in contrast to the broad beams of daylight Sun).

The year was divided into summer and winter - like day and night. They were 'born' (hanau) in spring (in the morning of the year) respectively in the evening of the year.

... In north Asia the common mode of reckoning is in half-year, which are not to be regarded as such but form each one separately the highest unit of time: our informants term them 'winter year' and 'summer year'. Among the Tunguses the former comprises 6½ months, the latter 5, but the year is said to have 13 months; in Kamchatka each contains six months, the winter year beginning in November, the summer year in May; the Gilyaks on the other hand give five months to summer and seven to winter. The Yeneseisk Ostiaks reckon and name only the seven winter months, and not the summer months. This mode of reckoning seems to be a peculiarity of the far north: the Icelanders reckoned in misseri, half-years, not in whole years, and the rune-staves divide the year into a summer and a winter half, beginning on April 14 and October 14 respectively. But in Germany too, when it was desired to denote the whole year, the combined phrase 'winter and summer' was employed, or else equivalent concrete expressions such as 'in bareness and in leaf', 'in straw and in grass' ... The arms held high in front (in Ba10-5--6) have signs of the dry sugarcane straw (toa) respectively of offspring, 'fruits' (hua) - as yet not counted (fallen). ... The practice of turning down the fingers, contrary to our practice, deserves notice, as perhaps explaining why sometimes savages are reported to be unable to count above four. The European holds up one finger, which he counts, the native counts those that are down and says 'four'. Two fingers held up, the native counting those that are down, calls 'three'; and so on until the white man, holding up five fingers, gives the native none turned down to count. The native is nunplussed, and the enquirer reports that savages can not count above four ... Together they constituted the water cycle of life; kua hakaora ia raua - kua hora koia. Together they produced offspring; kua hakatetea ko raua. ... He was moreover confronted with identifications which no European, that is, no average rational European, could admit. He felt himself humiliated, though not disagreeably so, at finding that his informant regarded fire and water as complementary, and not as opposites. The rays of light and heat draw the water up, and also cause it to descend again in the form of rain. That is all to the good. The movement created by this coming and going is a good thing. By means of the rays the Nummo draws out, and gives back the life-force. This movement indeed makes life. The old man realized that he was now at a critical point. If the Nazarene did not understand this business of coming and going, he would not understand anything else. He wanted to say that what made life was not so much force as the movement of forces. He reverted to the idea of a universal shuttle service. 'The rays drink up the little waters of the earth, the shallow pools, making them rise, and then descend again in rain.' Then, leaving aside the question of water, he summed up his argument: 'To draw up and then return what one had drawn - that is the life of the world' ...

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||