57. Let's now take a quick look at the maitaki glyphs in the G text. The pure examples, those without added elements, are 6 in number:

And should we disregard the last one because it has been drawn faint (weak like a newborn child), there will remain 5 of them - all on side a. Gb4-27 is similar to 3 of those on side a but it is special both because it is faint and because it is alone on side b:

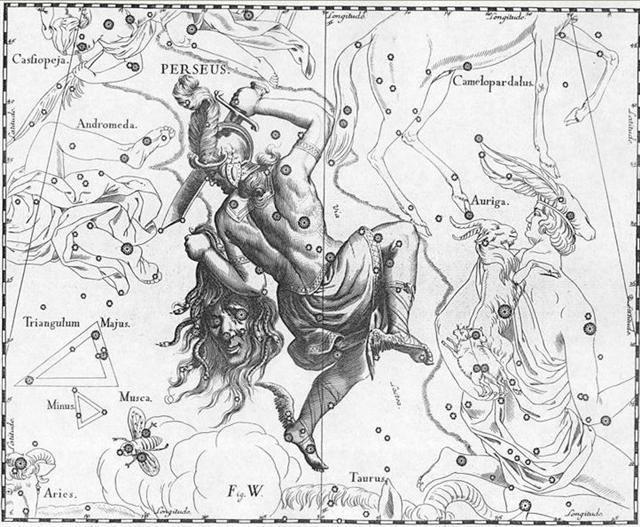

... In the sky, Perseus lies next to his beloved Andromeda. Nearby are her parents Cepheus and Cassiopeia, as well as the monster, Cetus, to which she was sacrificed. Pegasus, the winged horse, completes the tableau. Perseus himself is shown holding the Gorgon’s head. The star that Ptolemy called ‘the bright one in the Gorgon head’ is Beta Persei, named Algol from the Arabic ra’s al-ghul meaning the demon’s head. (As an aside, al-ghul is also the origin of our word alcohol - quite literally ‘the demon drink’. Algol is the type of star known as an eclipsing binary, consisting of two close stars that orbit each other, in this case every 2.9 days ... ... Algol, the Demon, the Demon Star, and the Blinking Demon, from the Arabians' Rā's al Ghūl, the Demon's Head, is said to have been thus called from its rapid and wonderful variations; but I find no evidence of this, and that people probably took the title from Ptolemy. Al Ghūl literally signifies a Mischief-maker, and the name still appears in the Ghoul of the Arabian Nights and of our day. It degenerated into the Alove often used some centuries ago for this star ... With astronomical writers of three centuries ago Algol was Caput Larvae, the Spectre's Head ...

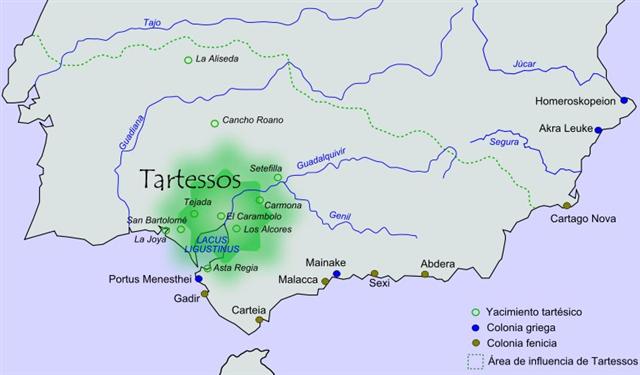

... The myth is that Perseus was sent to cut off the head of the snaky-locked Gorgon Medusa, a rival of the Goddess Athene, whose baleful look turned men into stone, and that he could not accomplish the task until he had gone to the three Graeae, 'Grey Ones', the three old sisters of the Gorgons who had only one eye and one tooth between them, and by stealing eye and tooth had blackmailed them into telling him where the grove of the Three Nymphs was to be found. From the Three Nymphs he then obtained winged sandals like those of Hermes, a bag to put the Gorgon's head into, and a helmet of invisibility. Hermes also kindly gave him a sickle; and Athene gave him a mirror and showed him a picture of Medusa so that he would recognize her. He threw the tooth of the Three Grey Ones, and some say the eye also, into Lake Triton, to break their power, and flew on to Tartessus where the Gorgons lived in a grove on the borders of the ocean; there he cut off the sleeping Medusa's head with the sickle, first looking into the mirror so that the petrifying charm should be broken, thrust the head into his bag, and flew home pursued by other Gorgons ...

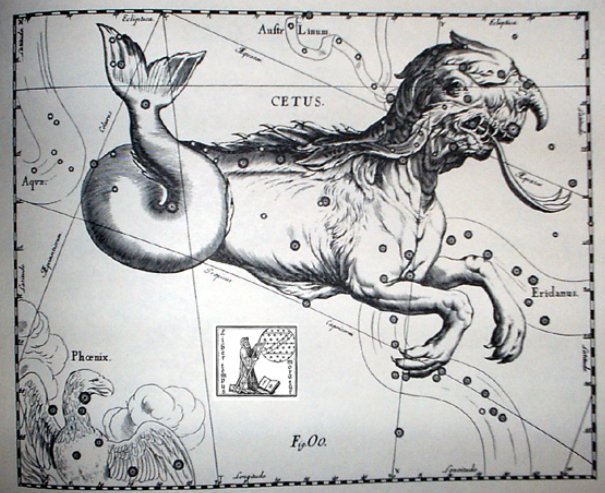

... This constellation [Cetus] has been identified, at least since Aratos' day, with the fabled creature sent to devour Andromeda, but turned to stone at the sight of the Medusa's head in the hand of Perseus. Equally veracious additions to the story, from Pliny and Solinus, are that the monster's bones were brought to Rome by Scaurus, the skeleton measuing forty feet in length and the vertebrae six feet in circumference; from Saint Jerome, who wrote that he had seen them at Tyre; and from Pausanias, who described a nearby spring that was red with the monster's blood ...

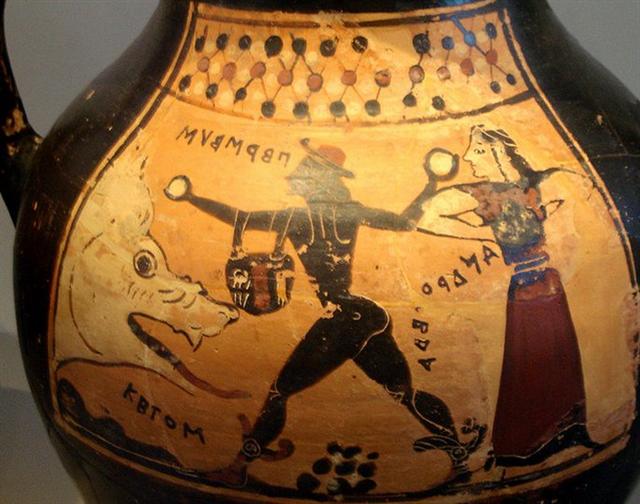

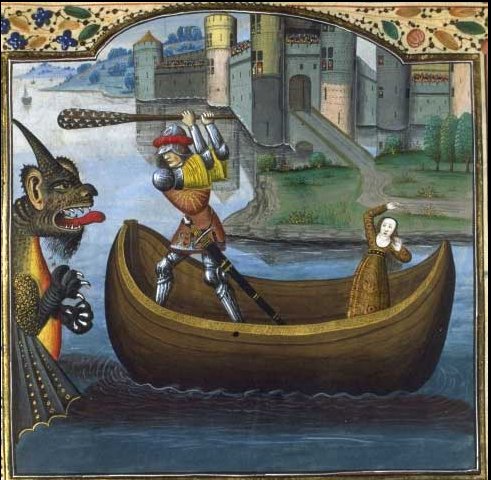

... Hipparchos and Pliny made a separate constellation of the Gorgon stars as the Head of Medusa, this descending almost to our own day, although always connected with Perseus. The Hebrews knew Algol as Rōsh ha Sātān, Satan's Head, Chilmead's Rosch hassatan, the Divels head; but also as Lilith, Adam's legendary first wife, the nocturnal vampyre from the lower world that reappeared in the demonology of the Middle Ages as the witch Lilis, one of the characters in Goethe's Walpurgis Nacht ... ... A title [for Perseus] popular at one time, and still seen, was the Rescuer, for, according to the story, Perseus, when under obligations to furnish a Gorgon's head to Polydectes, found the Sisters asleep at the Ocean; and using the shield of Minerva as a mirror, that he might not be petrified by Medusa's glance, cut off her head, which he then utilized in the rescue of Andromeda ... ... On condition that, if he rescued her, she should be his wife and return to Greece with him, Perseus took to the air again, grasped his sickle and, diving murderously from above, beheaded the approaching monster, which was deceived by his shadow on the sea. He had drawn the Gorgon's head from the wallet, lest the Monster might look up, and now laid it face downwards on a bed of leaves and sea-weed (which immediately turned to coral), while he cleansed his hands of blood, raised three altars and sacrificed a calf, a cow, and a bull to Hermes, Athene, and Zeus respectively ...

... Perhaps the most enduring of all Greek myths is the story of Perseus and Andromeda, the original version of George and the dragon. Its heroine is beautiful Andromeda, the daughter of the weak King Cepheus of Ethiopia and the vain Queen Cassiopeia, whose boastfulness knew no bounds. Andromeda’s misfortunes began one day when her mother claimed that she was more beautiful even than the Nereids, a particularly alluring group of sea nymphs. The affronted Nereids decided that Cassiopeia’s vanity had finally gone too far and they asked Poseidon, the sea god, to teach her a lesson. In retribution, Poseidon sent a terrible monster (some say also a flood) to ravage the coast of King Cepheus’s territory. Dismayed at the destruction, and with his subjects clamouring for action, the beleaguered Cepheus appealed to the Oracle of Ammon for a solution. He was told that he must sacrifice his virgin daughter to appease the monster. ['His subjects had therefore obliged him to chain her to a rock, naked except for certain jewels, and leave her to be devoured.' Copied by me from Robert Graves, The Greek Myths.] Hence the blameless Andromeda came to be chained to a rock to atone for the sins of her mother, who watched from the shore with bitter remorse. The site of this event is said to have been on the Mediterranean coast at Joppa (Jaffa), the modern Tel-Aviv. As Andromeda stood on the wave-lashed cliffs, pale with terror and weeping pitifully at her impending fate, the hero Perseus happened by, fresh from his exploit of beheading Medusa the Gorgon. His heart was captivated by the sight of the frail beauty in distress below. The Roman poet Ovid tells us in his book the Metamorphoses that Perseus at first almost mistook her for a marble statue. Only the wind ruffling her hair and the warm tears on her cheeks showed that she was human. Perseus asked her name and why she was chained there. Shy Andromeda, totally different in character from her vainglorious mother, did not at first reply; even though awaiting a horrible death in the monster’s slavering jaws, she would have hidden her face modestly in her hands, had they not been bound to the rock. Perseus persisted in his questioning. Eventually, afraid that her silence might be misinterpreted as guilt, she told Perseus her story, but broke off with a scream as she saw the monster breasting through the waves towards her. Pausing politely to ask the permission of her parents for Andromeda’s hand in marriage, Perseus swooped down, slew the sea-dragon with his diamond sword, released the swooning girl to the enthusiastic applause of the onlookers and claimed her for his bride. Andromeda later bore Perseus six children including Perses, ancestor of the Persians, and Gorgophonte, father of Tyndareus, king of Sparta ...

... Heracles's rescue of Hesione, parallelled by Perseus's rescue of Andromeda ... is clearly derived from an icon common in Syria and Asia Minor: Marduk's conquest of the Sea-monster Tiamat, an emanation of the goddess Ishtar, whose power he annulled by chaining her to a rock. Heracles is swallowed by Tiamat, and disappears for three days before fighting his way out. So also, according to a Hebrew moral tale apparently based on the same icon, Jonah spent three days in the Whale's belly; and so Marduk's representative, the king of Babylon, spent a period in demise every year, during which he was supposedly fighting Tiamat ... Marduk's or Perseus's white solar horse here becomes the reward for Hesione's rescue. Heracles's loss of hair emphasizes his solar character: a shearing of the sacred king's locks when the year came to an end, typified the reduction of his magical strength, as in the story of Samson ... When he reappeared, he had no more hair than an infant ...

...Then the big Fish did swallow him, and he had

done acts worthy of blame.

But

We cast him forth on the naked shore in a state

of sickness, |