247. Yesterday evening,

happening on

another TV-program, I saw a Hawaiian woman who chuckled when interviewed

about what memories remained after Captain

Cook's visit to the island 240 years

earlier. Let's remind ourselves:

... Cook's first visit, to Kaua'i Island in

January 1778, fell within the traditional

months of the New Year rite (Makahiki).

He returned to the Islands late in the same

year, very near the recommencement of the

Makahiki ceremonies. Arriving now off

northern Maui, Cook proceeded to make a

grand circumnavigation of Hawai'i Island in

the prescribed clockwise direction of Lono's

yearly procession, to land at the temple in

Kealakekua Bay where Lono begins and ends

his own circuit.

The British captain took his leave in early

February 1779, almost precisely on the day

the Makahiki ceremonies closed. But on his

way out to Kahiki, the Resolution sprung a

mast, and Cook committed the ritual fault of

returning unexpectedly and unintelligibly.

The Great Navigator was now hors

catégorie, a dangerous condition as

Leach and Douglas have taught us, and within

a few days he was really dead - though

certain priests of Lono did afterward ask

when he would come back ...

... Nevertheless, by virtue of a series of

spectacular coincidences, Cook made a

near-perfect ritual exit on the night of 3

February. The timing itself was nearly

perfect, since the Makahiki rituals

would end 1 February (±1 day), being the

14th day of the second Hawaiian month [Kau-lua].

This helps explain Mr. King's entry for 2

February in the published Voyage: 'Terreoboo

[Kalaniopu'u] and his Chiefs, had,

for some days past, been very inquisitive

abouth the time of our departure' - to which

his private journal adds, '& seem'd well

pleas'd that it was soon'. Captain Cook,

responding to Hawaiian importunities to

leave behind his 'son', Mr. King [sic!], had even

assured Kalaniopu'u and the high

priest that he would come back again the

following year. Long after they had killed

him, the Hawaiians continued to believe this

would happen.

With the high priest's permission, the

British just before leaving removed the

fence and certain images of Hikiau

temple for firewood. Debate raged in the

nineteenth century about the role of this

purported 'sacriledge' in Cook's death,

without notice, however, that following

Lono's sojourn the temple is normally

cleared and rebuilt - indeed, the night the

British left one of the temple houses was

set on fire. Among the other ritual coincidences, perhaps

the most remarkable was the death of poor

old Willie Watman, seaman A. B., on the

morning of 1 February. Watman was the first

person among Cook's people to die at

Kealakekua: on the ceremonial day, so far as

can be calculated, that the King's living

god Kahoali'i would swallow the eye of the

first human sacrifice of the New Year. And

it was the Hawaiian chief - or by one

account, the King himself - who specifically

requested that old Watman be buried at

Hikiau temple.

Messrs. Cook and King read the burial

service, thus introducing Christianity to

the Sandwich Islands, with the assistance

however of the high priest Ka'oo'oo and the

Lono 'brethren', who when the English had

finished proceeded to make sacrifices and

perform ceremonies at the grave for three

days and nights.

So in the early hours of 4 February, Cook

sailed out of Kealakekua Bay, still alive

and well. The King, too, had survived Lono's

visit and incorporated its tangible

benefits, such as iron adzes and daggers. In

principle, the King would now make

sacrifices to Kuu and reopen the

agricultural shrines of Lono. The normal

cosmic course would be resumed.

Hence the ultimate ritual coincidence, which

was meteorological: one of the fertilizing

storms of winter, associated with the advent

of Lono, wreaked havoc with the foremast of

the Resolution, and the British were forced

to return to Kealakekua for repairs on 11

February 1779

...

Mr. King remarks that there were not as

many hundreds of people at their return to

Kealakekua as there had been thousands when

they first came in. A tabu was in effect,

which was ascribed to the king's absence. By

the best evidence, the British had

interrupted the annual bonito-fishing rite,

the transition from the Makahiki season to

normal temple ceremonies. Cook was now

hors cadre. And things fell apart

...

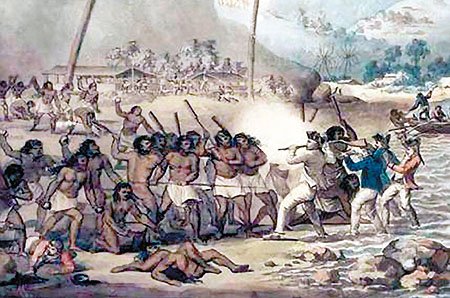

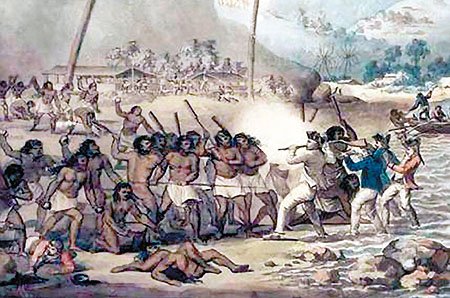

... Early on Sunday morning, 14 February 1779, Captain Cook went ashore with a

party of marines to take the Hawaiian king,

Kalaniopu'u, hostage against the return of

the Discovery's cutter, stolen the night

before in a bold maneuver - of which,

however, the amiable old ruler was

innocent. At the decisive moment, Cook and

Kalaniopu'u, the God and the King, will

confront each other as cosmic adversaries. Permit me thus an anthropological reading of

the historical texts. For in all the

confused Tolstoian narratives of the affray

- among which the judicious Beaglehole

refuses to choose - the one recurrent

certainty is a dramatic structure with the

properties of a ritual transformation.

During the passage inland to find the king,

thence seaward with his royal hostage, Cook

is metamorphosed from a being of veneration

to an object of hostility. When he came

ashore, the common people as usual dispersed

before him and prostrated face to earth; but

in the end he was himself precipitated face

down in the water by a chief's weapon, an

iron trade dagger, to be rushed upon by a

mob exulting over him, and seeming to add to

their own honors by the part they could

claim in his death: 'snatching the daggers

from each other', reads Mr. Burney's

account, 'out of eagerness to have their

share in killing him'. In the final ritual

inversion, Cook's body would be offered in

sacrifice by the Hawaiian King ...

The Hawaiian woman who was interviewed chuckled because the assassination of Captain

Cook coincided with the day we have named All Hearts' Day

- when in February 14 (2-14) the war-god Kuu

returned to power. The assassination of

Julius Caesar came a month (29 days) later

(and 365 - 29 = 336 = 14 * 24 = 12 * 28):

... The brutes of spring caused the downfall

of both Captain Cook and Julius Caesar. We

are close to the key myth of mankind, that

which explains the regeneration of sun and

of growth. Once at least some people kept

the tradition living. I became interested in

what really happened at March 15 and

reopened Henrikson to find out: Caesar had

been forewarned of the threat by the prophet

Spurinna, who told him that a great threat

was coming at Idus Martiae or

just before [i.e. at 3-14]. The day arrived

and Caesar was still living, walking to his

meeting with the Senate when he happened to

encounter Spurinna and told him jokingly

that he was still alive. Spurinna calmely

answered that the day had yet not ended.

The Romans divided their months in two parts

and the dividing point was Idus,

which in some way was connected with full

moon. March 15 was the midpoint of March,

which is close to spring equinox. The old

agricultural year defined the beginning of

the year to the time when sun returned, and

it was connected with Mars

...

The old year ended at February 1 - when

poor old Willie Watman died - when the king's

living god Kahoali'i swallowed

the eye of the first human sacrifice of the

New Year.

... in the ceremonial course of the coming

year, the king is symbolically transposed

toward the Lono pole of Hawaiian

divinity ... It need only be noticed that

the renewal of kingship at the climax of the

Makahiki coincides with the rebirth

of nature. For in the ideal ritual calendar,

the kali'i battle follows the

autumnal appearance of the Pleiades, by

thirty-three days - thus precisely, in the

late eighteenth century, 21 December, the

winter solstice. The king returns to power

with the sun. Whereas, over the next two

days, Lono plays the part of the

sacrifice. The Makahiki effigy is

dismantled and hidden away in a rite watched

over by the king's 'living god',

Kahoali'i or

'The-Companion-of-the-King', the one who is

also known as 'Death-is-Near' (Koke-na-make).

Close kinsman of the king as his ceremonial

double, Kahoali'i swallows the eye of

the victim in ceremonies of human sacrifice

...

... In the morning of the world, there was

nothing but water. The Loon was calling, and

the old man who at that time bore the

Raven's name, Nangkilstlas, asked her

why. 'The gods are homeless', the Loon

replied. 'I'll see to it', said the old man,

without moving from the fire in his house on

the floor of the sea. Then as the old man

continued to lie by his fire, the Raven flew

over the sea. The clouds broke. He flew

upward, drove his beak into the sky and

scrambled over the rim to the upper world.

There he discovered a town, and in one of

the houses a woman had just given birth.

The Raven stole the skin and form of the

newborn child. Then he began to cry for

solid food, but he was offered only mother's

milk. That night, he passed through the town

stealing an eye from each inhabitant. Back

in his foster parents' house, he roasted the

eyes in the coals and ate them, laughing.

Then he returned to his cradle, full and

warm. He had not seen the old woman watching

him from the corner - the one who never

slept and who never moved because she was

stone from the waist down. Next morning,

amid the wailing that engulfed the town, she

told what she had seen. The one-eyed people

of the sky dressed in their dancing clothes,

paddled the child out to mid-heaven in their

canoe and pitched him over the side

...

Next date came 10 days later, in the midst

of the annual bonito-fishing rite:

... the British were forced to return to

Kealakekua for repairs on 11 February 1779

...

Mr. King remarks that there were not as

many hundreds of people at their return to

Kealakekua as there had been thousands when

they first came in. A tabu was in effect,

which was ascribed to the king's absence. By

the best evidence, the British had

interrupted the annual bonito-fishing rite,

the transition from the Makahiki season to

normal temple ceremonies. Cook was now

hors cadre. And things fell apart

...

... I'a

is the general

name for

fishes,' Pratt

notes in his

Samoan

dictionary,

'except the

bonito and

shellfish

(mollusca and

crustacea).'

We may forgive

the inaccuracy

of the biology

in our gratitude

for the former

note. The bonito

is not a fish,

the bonito is a

gentleman, and

not for worlds

would Samoa

offend against

his state. The

Samoan in his

'upu fa'aaloalo

has his own

Basakrama, the

language of

courtesy to be

used to them of

high degree, to

chiefs and

bonitos.

One does not say

that he goes to

the towns which

are favorably

situated for the

bonito fishery;

he says rather

that (funa'i)

he goes into

seclusion, he

withdraws

himself. He

finds that the

fleet which is

to chase the

bonito has an

honourable name

for this use,

that the chief

fisher has a

name that he

never uses

ashore. He will

not in so many

words say that

he is going to

fish for bonito,

he says that he

is going out

paddling in the

courtesy

language (alo);

he even avoids

all chance of

offending this

gentleman of his

seas by saying,

instead of the

blunt vulgarity

of the word

fishing, rather

that he is

headed in some

other direction

(fa'asanga'ese).

He does not

paddle with the

common word but

with that (pale)

which he uses in

compliment to

his chief's

canoe. He will

not so much as

speak the word

which means

canoe; he calls

it by another

word (tafānga),

which may mean

the turning away

to one side.

In this

unmentioned

canoe he may not

carry water by

its common name,

he must call it

(mālū)

the cool stuff.

He will not

mention his eyes

in the canoe; he

calls his visor

(taulauifi)

the shield for

his chestnut

leaves.

Even the word

for large

becomes

something else (sumalie)

in this great

game. The hook

must be tied

with ritual

care; it is

called (pa)

out of the

common name for

hook; no bonito

will take a hook

which has not

been properly

tied; the

fastening is

veiled under the

name (fanua)

for the land.

There are many

rules to

observe; their

disregard is

called (sopoliu)

the stepping

over the bilges,

from the most

unfortunate

thing that the

fisher can do.

He may hail the

bonito by his

name (atu),

or he may call

him

affectionately

or coaxingly (pa'umasunu)

old singed-skin.

If he has the

fortune to hook

his bonito he

must raise the

shout of

triumph,

Tu! Tu! Tu e!,

not his whole

name but one of

its syllables;

he triumphs as

over a foe

honorably slain

in combat, but

he avoids

hurting the

feelings of the

other gentlemen

of the sea.

The first bonito

caught in a new

canoe he calls (ola)

life; the first

bonito caught in

any season bears

a special name (ngatongiā),

of uncertain

signification,

and he presents

it to his chief.

His catch he

reckons by a

special

notation; to his

numerals he adds

the word (tino)

body; he counts

them as

one-body,

two-body,

three-body.

Parts of the

gentleman have

specific names

of their own;

his fins (asa)

and his entrails

(fe'afe'a)

are called in

terms nowhere

else employed;

the tidbit of

the belly part,

which the fisher

must give to his

chief, is called

(ma'alo)

by the honorific

title of the

chief's abdomen.

And if the rites

were not duly

observed, if the

hook was not

rightly tied, if

the fisher was

so incautious as

to mention his

eyes, if one of

a hundred faults

was committed

and the fishing

was in vain,

then the fisher

acknowledged his

ill success

abjectly by

saying that (maloā)

he was

conquered. Such

is the language

Samoans use to

the gentleman of

the seas, and he

is not

i'a

...

|

After 13 days counted from the beginning of

the new year (i.e. 3 days after 11 February) came the transformation to

the war-god

Kuu.

...

In many Polynesian cultures the bodies of

gods were conceived of as covered with

feathers and they were frequently associated

with birds: in Tahiti and the Society

Islands, bird calls on the marae

signaled the presence of the gods. Hawaiian

feathered god figures generally depict only

the head and neck of the god ...

Day 45 (= 31 + 14) counted from January 1 was February

14 (2-14), and 354 + 45 = 399 (or counting

also day zero: 400).

... Taw,

Tav or Taf is the

twenty-second and last letter in many

Semitic abjads ... In gematria Tav

represents the number 400, the largest

single number that can be represented

without using the Sophit forms ...

... Lau,

s. Haw., to feel for, spread out,

expand, be broad, numerous; s. leaf

of a tree or plant, expanse, place where

people dwell, the end, point; sc. extension

of a thing; the number four hundred ...

... Murzim

[β Canis Majoris], generally

but less correctly Mirzam, and occasionally

Mirza, is from Al Murzim, the

Announcer², often combined by the Arabs with

β

Canis Minoris in the plural Al Mirzamāni,

or as Al Mirzamā al Shi'rayain,

the two Sirian Announcers; Ideler's idea of

the applicability of this title being that

this star announced the immediate rising of

the still brighter Sirius.

² Literally the Roarer, and so another of

the many words in the Arabic tongue for the

lion, of which that people boasted of having

four hundred ...

... The Sacred Book of the ancient Maya

Quiche, the famous Popol Vuh (the

Book of Counsel) tells of Zipacna, son of

Vucub-Caquix (= Seven Arata). He sees 400

youths dragging a huge log that they want as

a ridgepole for their house. Zipacna alone

carries the tree without effort to the spot

where a hole has been dug for the post to

support the ridgepole. The youths, jealous

and afraid, try to kill Zipacna by crushing

him in the hole, but he escapes and brings

down the house on their heads. They are

removed to the sky, in a 'group', and the

Pleiades are called after them

...

There was a connection between the youths in

the Pleiades and a cycle of 400.

... The word lau, in

the sense of expanse, and hence 'the sea,

ocean', is not now used in the Polynesian

dialects. There remain, however, two

compound forms to indicate its former use in

that sense: lau-make, Haw., lit. the

abating or subsiding of water, i.e.,

drought; rau-mate, Tah., to cease

from rain, be fair weather; rau-mate,

N. Zeal., id., hence summer .The

other word is koo-lau, Haw.,

kona-rau, N. Zeal., toe-rau,

Tah., on the side of the great ocean, the

weather side of an island or group;

toa-lau, Sam., the north-east trade

wind. In Fiji, lau is the name of the

windward islands generally. In the Malay and

pre-Malay dialects that word in that sense

still remains under various forms: laut,

lauti, lautan, lauhaha,

olat, wolat, medi-laut,

all signifying the sea, on the same

principle of derivation as the Latin

æquor,

flat, level, expanse, the sea

...

... In the description of the Babylonian

zodiac given in the clay tablets known as

the MUL.APIN, the constellation now known as

Aries was the final station along the

ecliptic. It was known as MULLÚ.ḪUN.GÁ,

'The Agrarian Worker'.

The MUL.APIN is held to have been compiled

in the 12th or 11th century BCE, but it

reflects a tradition which takes the

Pleiades as marking vernal equinox, which

was the case with some precision at the

beginning of the Middle Bronze Age (early

3rd millennium BCE) ...

... One of the youths said to Ira,

'Why do we want heaps of stone?' Ira

replied, 'So that we can all ask the stones

to do something.' They took (the material)

for the stone heaps (pipi horeko) and

piled up six heaps of stone at the outer

edge of the cave. Then they all said to the

stone heaps, 'Whenever he calls, whenever he

calls for us, let your voices rush (to him)

instead of the six (of us) (i.e., the six

stone heaps are supposed to be substitutes

for the youths). They all drew back to

profit (from the deception) (? ki honui)

and listened. A short while later, Kuukuu

called. As soon as he had asked, 'Where are

you?' the voices of the stone heaps replied,

'Here we are!' All (the youths) said, 'Hey,

you! That was well done!'

...

... another Alcyone, daughter of Pleione,

'Queen of Sailing', by the oak-hero Atlas,

was the mystical leader of the seven

Pleiads. The heliacal rising of the Pleiads

in May marked the beginning of the

navigational year; their setting marked its

end when (as Pliny notices in a passage

about the halcyon) a remarkably cold North

wind blows

...

... Pliny, who carefully describes the

halcyon's alleged nest - apparently the

zoöphyte called halcyoneum by

Linnaeus - reports that the halcyon is

rarely seen and then only at the winter and

summer solstices and at the setting of the

Pleiades. This proves her to have originally

been a manifestation of the Moon-goddess who

was worshipped at the two solstices as the

Goddess of alternatively Life-in-Death and

Death-in-Life - and who early in November,

when the Pleiades set, sent the sacred king

his summons to death

...

... The Mahabharata insists on six

as the number of the Pleiades [at the time

of rongorongo the triplet Alcyone, Pleione,

and Atlas were rising with the Sun in right

ascension day *56 and 6 * 56 = 336 = 365 -

29] as well as of

the mothers of Skanda and gives a

very broad and wild description of the birth

and the installation of Kartikeya 'by

the assembled gods ... as their

generalissimo', which is shattering,

somehow, driving home how little one

understands as yet. The least which can be

said, assuredly: Mars was 'installed' during

a more or less close conjunction of all

planets; in Mbh. 9.45 (p. 133) it is

stressed that the powerful gods assembled

'all poured water upon Skanda, even

as the gods had poured water on the head of

Varuna, the lord of waters, for

investing him with dominion'. And this

'investiture' took place at the beginning of

the Krita Yuga, the Golden Age

...

400 - 214 = 186, although there were

evidently 4 special days not to be counted,

because 214 + 182 = 396:

|

Counting the tresses of

Pachamama (the World Mother)

from right to left: |

|

1 |

26 |

78 |

1 |

29 |

90 |

|

2 |

26 |

2 |

30 |

|

3 |

26 |

3 |

31 |

|

4 |

25 |

104 |

4 |

34 |

124 |

|

5 |

26 |

5 |

31 |

|

6 |

27 |

6 |

30 |

|

7 |

26 |

7 |

29 |

|

Total = 396 = 182 + 214 |

|